It was the tragic loss of his mother in 2014 that forced Giacomo Tincani to take over winemaking at La Basia in Valtènesi on the western shores of Lake Garda. Elena Parona, an agronomist, had created an artisanal farm producing olive oil, honey, corn for polenta, flour as well as wines made from indigenous grapes.

The farming at La Basia is organic and the winemaking light-handed. The indigenous Groppello grape which makes a crisp, light-bodied red is the center of the production at La Basia. Another local red variety, Marzemino, produces a fuller-bodied wine. This hilly area of Lombardia benefits from both the warming effect of the nearby lake as well as cooling winds from the mountains to the north.

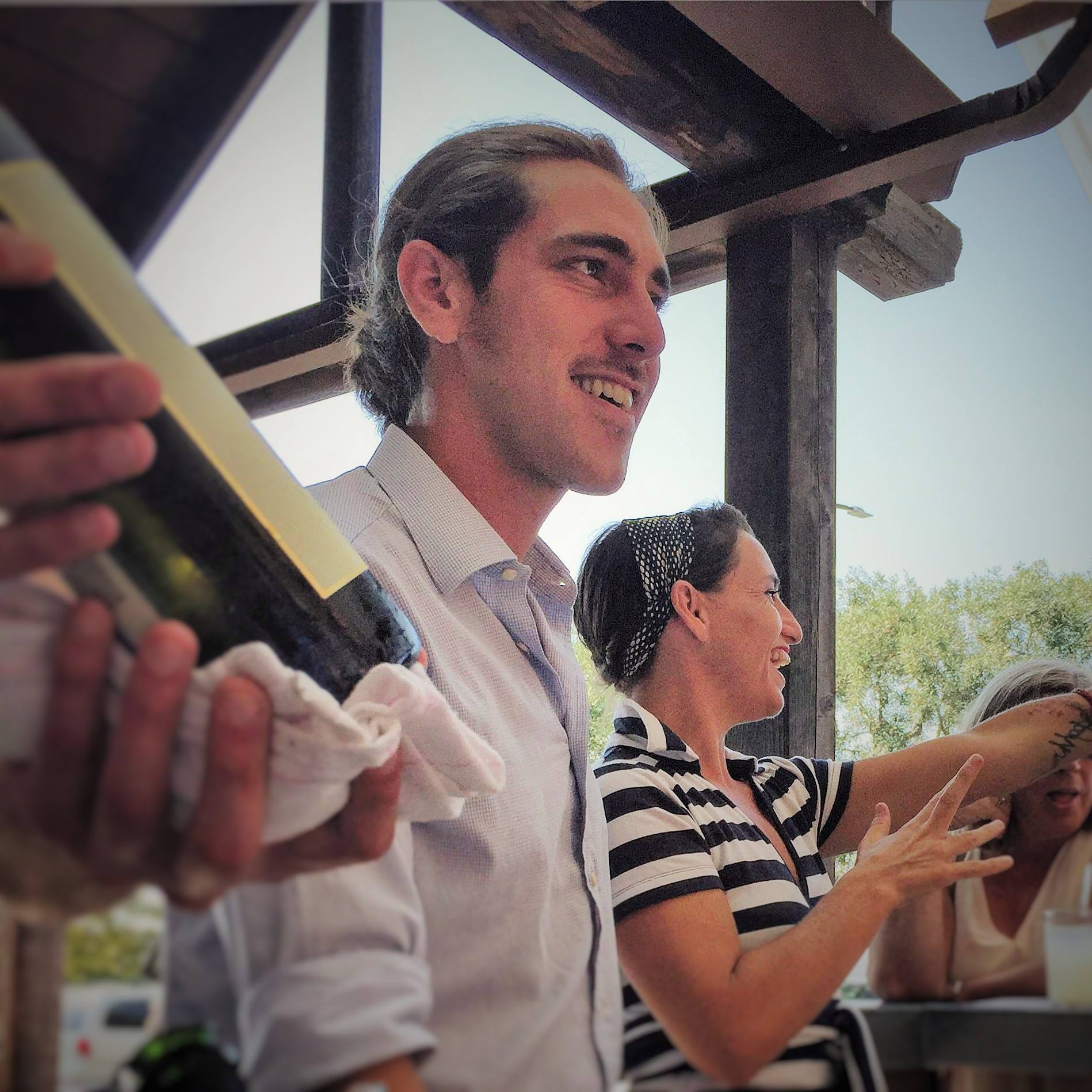

Giacomo Tincani talks to Grape Collective about running a family farm and the uniqueness of the Valtènesi DOC.

Christopher Barnes: Tell us about your family estate.

Christopher Barnes: Tell us about your family estate.

Giacomo Tincani: My family has been making wine in the Valtènesi region for 40 years, and my siblings and I are now the third generation on the land. Originally, it was a plot of land that my grandfather bought back in the '60s. He was not actually from that area. He was what you would call here more of a "gentleman farmer." He was a doctor in Milano, which is where I grew up. He bought the land and was mostly raising animals. He had cows, chickens and turkeys. He bought the piece of land that we're now working called La Basia, which is still the name of the winery of the estate. The land was mostly meant to provide feed for the animals, and the vineyard was mostly a side project. It was not his core activity.

When he decided to sell the business, my mom had just graduated in farming and agriculture. She decided to keep that plot of land where the vines were, and she then started her own business which she ran for the last 40 years up until she died in 2014.

Since then, my siblings and I took over the farm. I had been working with her for a while before, and one of my sisters was already working on the farm. It's still a fully-operational farm. We have crops, we have olive trees, we grow wheat, polenta and corn, and we run a mill as a cooperative with other farmers. We also have a riding school, so we board horses and teach people to ride.

That's a lot of activity!

Yes. It's a lot of activity, especially on a very small scale. The whole surface, the whole area that we work on is about 45 acres, so it's quite a small-scale operation. But we are really committed to preserving the rural aspect of what the business had been before, and we still want to run it as it is. My sister was already working on the farm with me, but she mostly works with the horses. So then we were the two children already working at the farm, and my other siblings joined in.

How long have you been making wine?

How long have you been making wine?

You mean me, myself? Our first harvest for my brother and me as winemakers was in 2014 when we first had to make our own decisions in the field.

It must have been a real tragedy having to take over in those circumstances. I can't imagine that. How did you cope with the responsibility, and were there things that you had to learn very, very quickly?

There are two main things. The first is that we went out and sought help. We were not private or too shy, to ask even the most simple questions to our colleagues when we had issues, when we had problems, or we had any doubts about the way we were doing things. The other thing that is really what has been very helpful for me to focus on is that we try, we've always tried, to develop a very traditional style of wine. We've always worked with the native grapes of our region. We've always tried to have and develop a product that is very connected to the soil and the region where it comes from. That tradition has a very reliable ground to base any next decision on, so that has been definitely helpful for me. Yes, I've wondered myself how that would feel otherwise if I didn't have that tradition to rely on.

Your vineyard is very near Lake Garda. Tell us about the lake and the different regions that surround it.

It’s very typical for Italy that in a pretty small surface area there are very, very different kinds of grapes, different kinds of soil, different kinds of styles that have developed over time according to each particular region, condition, and so on. All around the lake, there are actually very different kinds of wine and appellations. Starting from our side on the west shore of the lake, there's our region, Valtènesi. Down south at the bottom of the lake you would find Lugana. So Valtènesi is traditionally a region of red grapes, and our indigenous varietal is a red grape called Groppello. Down south, you find Lugana with its own grape, Turbiana, and on the other shore of the lake, you would find Bardolino with their own grapes, and going up little north, Valpolicella with Corvina, but it's all very, very close.

Overall, it would take an hour and a half drive to cover that area by driving on the highway. It would take an hour or so to drive from Brescia, our province, to Verona, the next one, and all of those regions are in between those two cities. It's a very diversified environment as much as any other region all over Italy. It's a land of differences.

(Photo: Elena Parona)

Giacomo, how would you describe the soil and the climate in Valtènesi?

The soil surrounding the lake and especially the southern part of the lake comes from what originally was the body—the actual body of water that is now the lake. It used to be a glacier. Like most of the alpine lakes that you would find going from west to east all over the country, they were a glacier. And all the deposits brought down from the mountains by those ancient glaciers are now laying down at the bottom of the lake. So our soils are layers of limestones and pebbles—it's very much a dry and light soil. It's not a very generous soil. You will find a little more sand down at the bottom of the lake, and on the western side, you would definitely see much rockier soil and pebbles. Our soils, especially, as we are right on top of the first hill facing the lake, and we are some four miles away from the lake at around 600 feet of elevation.

What impact does the lake have on your viticulture?

That's fascinating because Lake Garda is the largest lake in Italy. We're not talking about huge; it's not Lake Michigan, obviously, it’s probably half the size, or covers the whole sides of Italy, I don't know. But it's a big body of water and pretty deep. So its influence on the surrounding area is very comparable to the sea all around the Mediterranean. It's a very singular place where traditionally grapes but also olive trees, lemon trees and even capers have always been grown. So it's a little bit like the Mediterranean coast.

Does it get quite cold up there?

It gets cold, not extremely cold, and It rains. it snows over the winter but not too much. The grapes are not that sensitive to extreme cold conditions during the winter when they'll have leaves out, as happened over the last few weeks, but they’re definitely not as sensitive as other plants like the olive tree, which is way more sensitive. The presence of those crops and plants is a good example that it's still a very mellow season, even in winter. We get that kind of warmth and heat during the winter by the lake that slowly releases the heat that absorbs over the warmer season. At the same time, during the summer, we get fresh breezes blowing from up north that brings colder air from the mountains, so it's quite a special place to grow grapes.

In terms of the lake effect, there were a lot of problems in Europe this year with frost.

Yes.

Is the presence of the lake helpful in terms of frost?

Is the presence of the lake helpful in terms of frost?

The events that occurred a few weeks ago are absolutely unpredictable. And at this moment in the season, the lake can't really help very much. That was a very, very unusual situation, and from what I can tell, we luckily reported very little loss of our shoots, and that was mostly because we got the very early sun in the morning, so the coldest temperatures were registered around 6 a.m. That is right when the sun goes up and so we actually had most of the shoots under 80 centimeters, so whatever was down that first vine actually got hit by the frost, which luckily for us, is not a problem right now because they are not the shoots that are going to make fruit over the season. But when we had problems, we had a few plants that had been hit by the frost, and they were the ones that were a little more covered from the first rays of the morning sun.

Have you noticed global warming in your area?

I personally think that you got to, you need a lot of experience and a lot of season on your back to really be able to say something about this. It's obvious that I've seen different seasons, I've seen one very cold and rainy season two years ago, and I've seen a very hot one. I can't really give you an answer that could be really based on actual facts. I can't really tell.

Talk about Groppello. It's an indigenous grape only in your area, and it makes a very unique wine.

Yes. Groppello is our grape, it's the grape, and actually our region is defined by its presence. It's a very, very tiny area where this grape still exists, still survives, because if you want to put an acreage on that, it would be something around 2,000 acres, the overall surface where this grape is grown. And I would say that it resembles in many aspects a lot of those antique grapes that haven't been trained a lot over time that have been always specific of a single place and always belong to a rural environment where people used to grow grapes for themselves, for their own consumption. And it hasn't been a commercial product for a long time, up until few decades ago. So they are grapes that haven't been trained and still retain a lot of their wild profile, which means spicy tannins and wild fruit. It has a very fascinating character.

How would you describe Groppello for somebody who has never tasted it? Are there any other wines that you could describe that taste a little bit like it?

How would you describe Groppello for somebody who has never tasted it? Are there any other wines that you could describe that taste a little bit like it?

It's a hard question to answer, because you don't really know what people are used to. So I would make a comparison to other varietals that have a similar taste, but they are probably obscure grapes that most people wouldn't know, so it's hard, but sometimes it resembles something like Grenache with that peppery note, with that kind of profile.

You farm organically. Talk a little bit about the importance of organic farming in your winemaking process.

The choice of farming organically has always been a choice of quality before any other matter or, a matter of quality and a matter of sustainability in a way that it's not, I would say, the way that most likely it's advertised. But for us as growers and farmers, first and foremost, sustainability means we can still farm grapes and vines that are more than 60 years old. And we are now farming grapes that we hope to leave to somebody else to farm for another couple of years. So sustainability means to keep the fertility of the soil, to keep the health of the plants, and to train plants and fruits that can retain a balance. Farming organically means first of all, and, obviously a way to preserve the healthiness of our environment, which is the environment that we live in, which we want to keep safe and healthy for ourselves and for future generations.

Do you have a philosophy of winemaking?

I don't know, right now I am developing an identity myself as a winemaker, so I think that I inherited an identity that I'm carrying on, in a way. The more significant thing that I can say is that the guiding spirit of our idea of winemaking is basically to let the fruit express itself, that we grow it to make it recognizable or for the wine to be able to transmit and talk about the place where we work, the place where the grapes come from, and to help just let it develop in the way that requires as little intervention as possible.

And Groppello, is it a grape that you need oak with, or is it a grape that does better with stainless steel?

With Groppello, we work in a very delicate way because when you get a lot of those very spicy tannins and sometimes a little rough tannins, you don't want to extract very much from them. Usually, for the most simple bottling, for the most wine that we make, which is called La Botte Piena, it's the most traditional style of wine, we work with a very short maceration on the skins. And most of the time, the fermentation ends without skins, and then we work only with stainless steel.

And the best vintages are when we get a very ripe and very nicely developed tannin and fruit and good concentration, with Groppello, we make a wine that is meant to age longer. And with that wine, then we work with longer maceration, but then in that case, we use wood to help develop the tannin, make it round. But for the most simple wines, we just want to let them be bright and crisp and easy and get a lot of the freshness and then enhance that very particular profile that the grape has.

You took over winemaking from your mother. What kind of things did she teach you about winemaking?

You took over winemaking from your mother. What kind of things did she teach you about winemaking?

My mom was a very private person, and she was not really trying to make us do what she had done. So there hasn't been a lot of teaching. But obviously, we saw a lot of what she did, and we heard her speak a lot about what she used to do. And the thing that most resonated with me all the time was when she would talk about her vines in a way that very much resembled the way she was a mom. She really had this attitude of training and letting the plants develop their own fruit, and then let that fruit be the best that it can be without very much intervention, without wanting to guide that process, without much intention and will.