We’ll get to the legend of the pink cow in a minute, but first we want to ask you this: Can you name two rosé wines you drank last year that you can’t wait to have again now that it’s warmer? Can you name one?

Our guess is that most people can’t, even though Americans now spend spring and summer awash in rosé. The problem is that too many taste alike. They’re pleasant, generally inexpensive and often refreshing. And certainly there’s nothing wrong with any of that. But if you’ve come to expect nothing more than that from your rosé, you’re setting the bar way too low. Demand more!

We’ve tasted a few recently that crossed a higher bar. And we had one that knocked our socks off, making us rush to the phone to ask the winemaker: How the heck did you do that? The ones we’ve enjoyed demonstrate again that good rosé can be made from many grapes and in many regions. Here are some to look for that might be surprising:

--Domaine de Cala (Coteaux Varois en Provence) 2018. (41% Grenache, 35% Cinsalt, 15% Syrah, 6% Rolle aka Vermentino, and others.) Just a tinge of color, with a marvelous nose of honeysuckle, lime peel and wet stones. The taste of this dry wine is surprisingly rich, with honeydew melon-like lusciousness and grapefruit acidity. The finish is long, lovely and tart. Winemaker Bruno Tringali finds a remarkable balance of easy-drinkability and serious character. Great deal at $15.95. (The 2018 is just being rolled out now.)

--Wente Vineyards “Niki’s” Pinot Noir Rosé (Arroyo Seco, Monterey) 2018. Lovely pale-salmon color, 100% Pinot. Light on its feet and so crisp John thought, favorably, of a focused Sauvignon Blanc. Great sustainably grown fruit that’s tightly wound, with mouthwatering acidity. It’s better closer to cellar temperature than chilled. This inaugural release, conceived by viticulturist Niki Wente, from the family’s fifth generation, and made with her cousin and winemaker Karl, is impressive. $30 from the winery and in 20 states soon.

--Volage Rosé Brut Sauvage Crémant de Loire non-vintage. (100% Cabernet Franc.) Full-flavored, with some roasted nuts and plenty of minerals, especially on the finish. Red berries, but mostly Dottie thought of blood oranges. You can taste the care: Hand-picked and made the way Champagne is made, with the late wine maven Patrick Léon (Château Mouton Rothschild and Opus One, among others) consulting with winemaker Elodie Battais. It’s aged on the lees – dead yeast cells and other leftovers that just kind of hang around during fermentation and aging – for three years. Lees can add texture, flavor and a little weight to wines. This is a substantial bubbly, good with food.

So we were already impressed by some of the bottles we’d been sent to sample over the past couple of months. And then we were wowed.

The bottle in question was Eberle Winery “Côtes-du-Rôbles Rosé” 2018 from Paso Robles, made from 52% Grenache, 44% Syrah and 4% Viognier. It costs about $24. “Medium color. Very pretty, with red, pink and yellow highlights,” we wrote. “Smells juicy, like ripe strawberries. Good acidity and good fruit, with a little bit of a bite and a nice undertone of minerals. Super dry. NICE TEXTURE!”

Yes, we actually wrote that in capital letters in our notes. Texture is simply how a wine feels in your mouth – so some big Chardonnays might seem chewy, while some Sauvignon Blancs are much lighter, and some Rieslings have a shimmering vibrancy. Texture is a word that’s usually associated with reds and their tannins. To us, rosés, even good ones, don’t often have much texture despite being made from red-skinned grapes. They have pleasant tastes but they don’t give us much to chew on, either literally or intellectually.

But this wine had stunning texture. Even though we knew this wine was hard to find outside of the winery, we wanted to know the secret to such a fine rosé. It was time to call the unrelated Eberles.

We first met Gary Eberle in 1999 when we were all judges at the L.A. County Fair. Now 75, he is a pioneer of Paso Robles winemaking and a pioneer of Syrah in the U.S. He’s also a teddy bear of a man who is one of the more charming and humorous winemakers we’ve met. Over the years, we’ve liked his soulful reds and, in our book “Wine for Every Day and Every Occasion,” we recommended his Muscat Canelli as a great after-Thanksgiving-dinner wine because it’s “light as a feather.”

We first met Gary Eberle in 1999 when we were all judges at the L.A. County Fair. Now 75, he is a pioneer of Paso Robles winemaking and a pioneer of Syrah in the U.S. He’s also a teddy bear of a man who is one of the more charming and humorous winemakers we’ve met. Over the years, we’ve liked his soulful reds and, in our book “Wine for Every Day and Every Occasion,” we recommended his Muscat Canelli as a great after-Thanksgiving-dinner wine because it’s “light as a feather.”

(Photo: Gary Eberle with his wife Marcy)

Gary has seen the ups and downs of rosé. When he was studying wine in the early 1970s, he told us, “before the white wine revolution, in the premium end of the wine business, there were red wines and there was a strong emphasis on dry rosés – fruity but dry rosés. Then, the whole thing – I don’t want to say fiasco, but the whole thing with White Zinfandel became so popular with Americans – the pink blush wines. For a couple of decades, a serious wine drinker wouldn’t be caught dead drinking a pink wine because of the stigma.”

When he started his own winery in 1979, “I wouldn’t get near a rosé because I knew how difficult it was to sell it,” he told us. But then a grower offered him a great deal on a grape called Counoise, a Rhône Valley variety, and he made about 450 cases of rosé from it. Even with the help of an off-color joke about the pronunciation of the grape that we won’t repeat here, he still couldn’t sell it. He gave up after three vintages.

However, as he put it, “I’ve been in the industry long enough to recognize if there’s anything you made too much of, wait three years and there won’t be enough of it.”

On trips to France, and especially Provence, he fell in love with rosé anew and decided to give it another shot. At the same time, he decided to make Rhône-like blends – from grapes like Grenache, Syrah and Viognier – that would be easy-drinking and fun. “Bistro wines,” he calls them. He made a red from Grenache, Syrah, and Mourvèdre; a white from Grenache Blanc, Roussanne and Viognier; and a rosé.

And here is where the legend of the pink cow comes in. As with many legends, this one has some truth and some fancy.

And here is where the legend of the pink cow comes in. As with many legends, this one has some truth and some fancy.

(Illustration by Media Brecher)

Rosé is generally known as a cash cow for wineries because it can be made from young vines, produced pretty simply and then sold quickly – no expensive barrels, no capital-eating aging – and that is certainly true. That’s one reason there are so many inexpensive but perfectly nice rosés on the shelves.

However, this also runs up against another fact of the wine business: Once a kind of wine or wine region becomes known for low prices, it’s tough to break through and charge more even for well-made wines that deserve a higher price. Think about what happened to Australia after it became known as a “low-cost producer.” The outstanding, beautifully made but sometimes pricey wines from there had trouble finding a market, as the winemaker Chris Carpenter pointed out to us a few months ago.

“With some of the wines you can raise the price and nobody bats an eye, but things like the rosé, you just raise it a buck a bottle and it makes a significant difference,” Eberle told us.

Of the 30,000 cases of wine Eberle makes, only 673 cases are rosé and he sells out quickly. Why not make more? Because his winery is at capacity and he doesn’t want to go over that 30,000 figure, he said. Plus he makes more money on other wines, especially the Côtes-du-Rôbles red and white, “so it’s kind of dumb to make less of the CDR Blanc to make more rosé,” he said.

On the other hand, he added: “People say if you’re making more money making Viognier or CDR Blanc, why don’t give up making rosé and I can’t – I like it!”

So what’s the secret, we asked. Why is it so good? And what about that texture? At that point he turned us over to Chris Eberle, the winemaker since 2105.

Both men told us that they are not related as far as they can tell. “We have found that in the U.S. we do not have a common ancestor,” said Gary. Chris, 36, said they are doing “the whole ‘my ancestry’ thing and we’re waiting for the results.” In any event, they clearly are not related because Gary is a red wine guy and Chris says “my passion lies in white wines,” which we guess means they’re kind of a perfect pair for rosé.

Both men told us that they are not related as far as they can tell. “We have found that in the U.S. we do not have a common ancestor,” said Gary. Chris, 36, said they are doing “the whole ‘my ancestry’ thing and we’re waiting for the results.” In any event, they clearly are not related because Gary is a red wine guy and Chris says “my passion lies in white wines,” which we guess means they’re kind of a perfect pair for rosé.

(Photo: Winemaker Chris Eberle)

We asked Chris if rosé was fun to make or just something wineries had to do these days. He paused and then he laughed.

“Some years it’s fun and some years it’s not,” he said. The 2018, which he considers his best so far, was on the easier side because they just got access to a new, 50-acre vineyard of Grenache and the young vines produced lovely fruit for rosé. Still, he added, “It is very difficult to make a good rosé. You have to pay attention to details. I had six different lots of rosé. I used four different yeasts. I cold-settled. It’s extremely time-consuming. Timing is very key.”

So we were dying to ask: What about the texture? First, he said, the small amount of Viognier contributes to the texture. It’s mostly there for aromatics, he said, but Viognier’s slightly oily character adds some mouthfeel.

Second, just a small amount of the wine is made in the saignée method. Saignée is very controversial in the world of rosé. That’s when, during production of a red wine, a small amount of juice is bled off after a little bit of contact with red skins. This both creates rosé juice, which is then fermented separately as rosé, and also helps make the remaining red wine more concentrated. Many rosé aficionados talk about this as a byproduct like making glue from a Triple Crown horse, since the vineyard and the winemaking haven’t been focused on rosé from the start. But Chris said he uses this just a bit and it helps add to the texture.

Finally, he said, there are lees. “We do a little bit of lees stirring,” Chris said. “For four weeks we’ll stir the lees once a week. I’m a big fan of lees and spreading lees around everything. I’ll add the lees from this white to that one and I’ll keep doing it and keep doing it.

“So the rosé has a little bit of Grenache Blanc or Viognier lees – we’re not adding a whole lot, I’m talking about a bucket’s worth to an 1,800-gallon tank. So it’s nothing, but lees are magic.”

Think about that: A winemaker goes on and on about all of the geeky details of his winemaking and then, ultimately, talks about magic. It’s no wonder this rosé touched us so deeply.

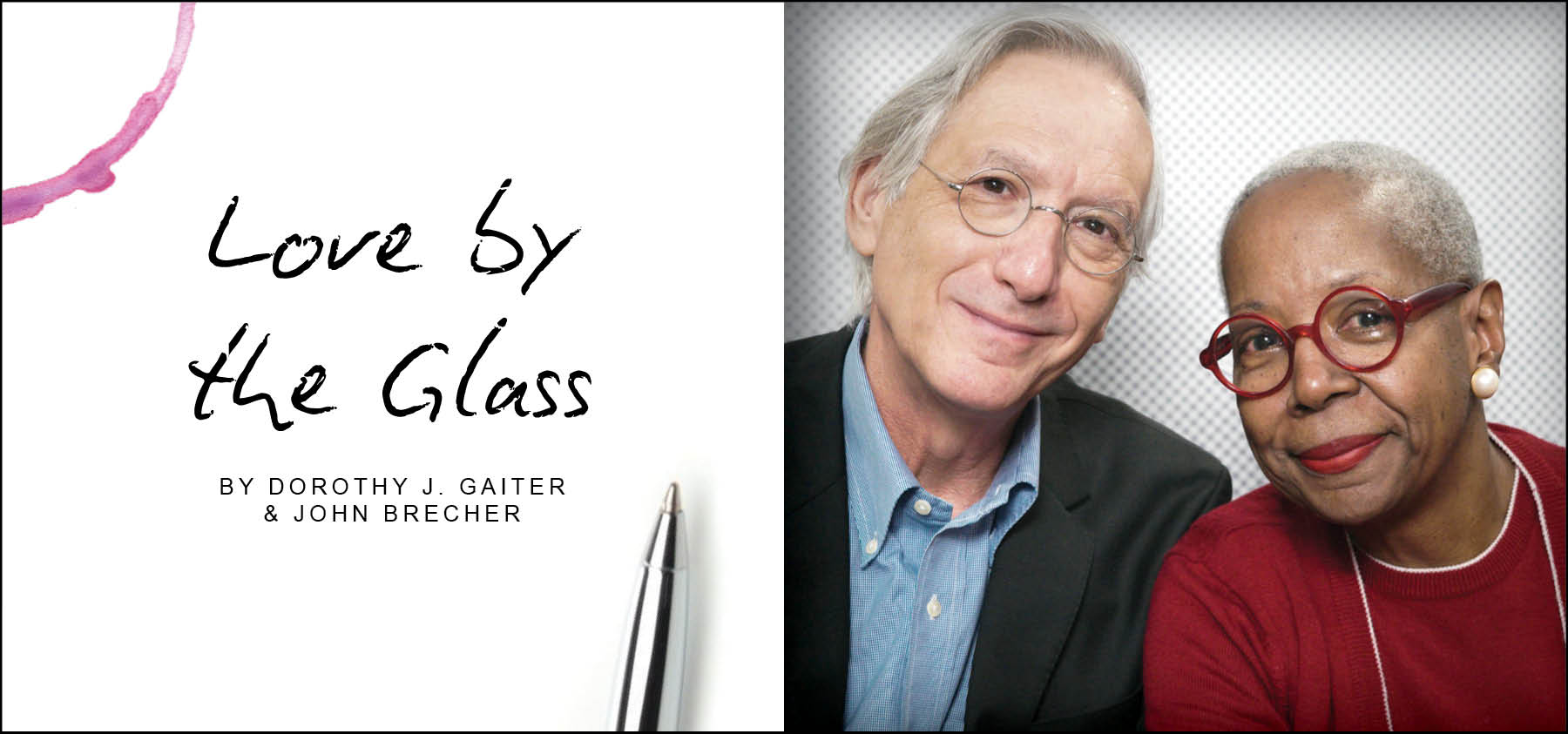

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective

Banner by Piers Parlett