Louis-Antoine Luyt has a little Indiana Jones about him. Instead of being an obtainer of rare antiquities, Luyt travels around the world sniffing out undiscovered vine treasures. A native Burgundian, he first arrived in Chile in 1998 as a 22-year-old traveler with the idea of exploring South America for three months. It was the start of a passionate relationship with the country, and he went on to became the leading advocate for País - the original grapes brought over from Spain by the missionaries.

Luyt ended up staying longer in Chile, finding a job as a dishwasher at a restaurant where he eventually worked his way up to become the wine buyer. While there, he was introduced to South America's only Master of Wine, Hector Vergara, who opened his eyes to the potential of Chilean wine.

Determined that there was something of great potential to unearth, Luyt returned to France in 2002 to learn winemaking, vowing to return to Chile when he was ready. While in France, he became friends with Matthieu Lapierre, son of Beaujolais natural wine pioneer Marcel, and worked five harvests at the estate.

Since his return to Chile, Luyt has helped to bring international attention to the Mission grape. País was first brought over in 1548 by the Spanish friar Francisco de Carabantes. That Chile has some of the world's oldest living vines is due to its natural barriers, Patagonia, the Pacific Ocean, the Andes and the Atacama desert. This has helped to prevent the arrival of phylloxera, the vine destroying louse that ravaged the vineyards of Europe and the United States.

He has hunted out old, disused or unappreciated vineyards from local growers in the far south of Chile. Luyt’s oldest vines have roots dating from 350 years back, or around 1660. He has continued the study of País in other countries, even taking on a País focused vineyard consulting project in Mexico.

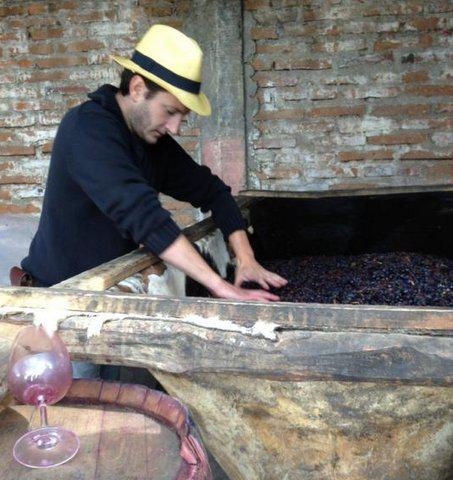

Luyt sources his fruit from 14 small family farmers who dry farm organically and who tend to their vineyards by horse plowing. The winemaking is very traditional and non-interventionist with the grapes being crushed by feet. He vinifies the grapes from each area separately, and the resulting wines are very different, illustrating the importance of terroir to the character of País.

Christopher Barnes: Louis-Antoine, tell us about the region of Bío Bío. It's very far south in Chile.

Louis-Antoine Luyt: It's quite far from the original and traditional normal Chilean region. We are 500 kilometers south from Santiago. Actually, the southwest region was originally planted in Chile along the Bío Bío River. You also have the Itata River, and we are between both. Maule is another river and region, and the south of Maule and Itata are very close. We buy and we have grapes from these three different river areas, and the Maule Valley is now the "new old" region. It has been this way for three or four years, and it's a very important region in the wine industry in Chile. It has been planted in continuity with vines for 500 years, mostly since the arrival of the Spanish.

There were three different parts where the Spanish planted vines 500 years ago. These include the north Limari Valley, the Aconcagua Valley in the middle near Valparaiso and Concepción, and the Maule region. In my project, we are looking for the oldest vineyards of these vines. They are mostly planted with Mission grapes.

How old are the vines that you're working with here?

The oldest vineyards where we source our grapes were planted in 1583. They are close to Yumbel. Yumbel is a small town, half an hour from here, and the Mission grapes are mostly between 200 and 400 years old. The other grapes that we picked up are Carignon and Cinsault and are more than 70 years old. They had been introduced in 1979. After 1979, the big earthquake that took place in Chile destroyed all the small cellars. They have since recreated some new cellars and have introduced them to old vineyards with some new grape varieties to produce different wines with more personality in order to be more competitive.

Talk about the Mission grapes. How did they get to Chile?

Talk about the Mission grapes. How did they get to Chile?

When the Spanish conquered America they brought olive trees and wheat.

Wheat. For bread?

Yes. Wheat.

Actually, the Spanish brought three important things to the region: olive trees, wheat and grapes. They introduced the Mission grapes. Actually, we saw that there is one Mission grape which is a black one called Negra Criolla. However, they brought five or six different grapes to Chile, some of which we can't find in North America. For the black grapes, it's Listan Prieto, also called Mission or País in Chile. You also have Moscatel de Alejandria, Pedro Ximénez, one that is called Corinth, and Torontel or Torrontes. Another grape for table grapes is Franciscano.

This Mission grape, the País, the black one, you find in Mexico, in Baja California. You find it in New Mexico and in Texas. You find it in California. You find it in Peru, and in many different countries including America. University studies have shown the grape's origins come from Spain, because we find the original grapes in the Canary Islands. Actually I don't know if in Spain they have Listan Prieto, but they have a grape called Listan negro. Even though prieto and negro mean the same thing, it doesn't mean that it's the same grape. There are studies being done on this, but it's true that the missionaries brought grapes from Spain with them.

It's very interesting. That's what I am surveying now in areas outside of Chile. I'm doing some consulting in Mexico and we find the same grapes and although we have different wines, many things work quite the same.

What are the characteristics of País and are they different in different areas?

Yes. First of all, when I decided to make wine with the País grape, it was like 15 years ago because someone here in the industry told me there is no way that you can make a good and fine wine with that. My mentality is to go where people say you can't go, so I asked why and if they had ever tried to make a fine wine with País. They told me no. That surprised me because how can you be that sure that it's not good if you haven't tried it. I first tried this one place and I realized that the wine was very singular. Because I drove many, many kilometers, I found some small farmers who are still producing some wines with these grapes.

From each place, the wines are different. Some things are the same, but many things are different. That means that there is truly identity, or like they say in Burgundy, terroir. Here in Chile, we have this opportunity that we have one grape which is owned by more than 2,000 people, and when they make their wines, they all have singularity. There are many identities in that. That's what I am doing now by making wines from the same grape, but from different small farmers. Like from 14 different farmers, from the same grapes, same kind of harvest, and same way of fermentation. That makes true differences.

What are the differences between the 14 different wines from the 14 different areas?

Exactly what they state in Burgundy, the terroir, and the last part of the terroir is the winemaker. You have the grapes and you also have the weather conditions and the earth and the grape variety. If you take grapes from Maule, you have wines which are generous in alcohol very early, and you get a large wine with quality. It is mostly the intensity that you can't find because of the age of the vines. The soils there are granitic, mainly clay. If you're talking about the Itata region close to the river, you have some terroir that looks like this with granitic soils, but you also have places where you just have sand and their wines are more floral and the identity is different.

In the Bío Bío region, you have wines that are lighter in alcohol, lighter in color, that have more intense spice or herbal notes. There are truly differences. When I am looking in the same region but with different soils, you also have different wines. That makes it very interesting for the wine lovers. That's something that we are not very used to in Chile, but it's represented in the wines.

With your winemaking, it's really not traditional winemaking in the sense that you would find in Napa or even most areas in France. There's almost like an archaeological element to what you're doing.

Yes. Actually when I started making wine, I repeated the wine process that I had learned and observed with friends in Beaujolais, which is carbonic maceration. It's full grapes in the tanks with no intervention in the wine process. Looking for identity, I started to look at the producers, the small farmers I'm working with, to observe their way of making wines because I was seduced by the wines I was tasting in their estates. Finally, I came back and my evolution has caused some to say, "Well, you need a press. There is no intervention for wine processing, but you need a press, you need technology to finish the wines."

To some, wine producers are just smashing grapes and punching down and that's the whole process. The traditional wine process has been around in the world forever. This process is easy, it's simple, and gives simple wines which is what I am looking for. I am not looking for premium wines. I am not looking to make the wines more expensive. I look to make wines that the people are able to accept and like and want to drink. I also make so many different wines with different terroir with the same techniques that give people who don't like this kind of flavor the opportunity to find the wine that they do like.

There is a social aspect in this. I am not owning any vineyard. It's with the Mission grapes. It's small farmers, small families. We're working with them trying to improve their economy, giving good money for the grapes, protecting the patrimony which is involved in those 200 or 400-year-old vines is something very special and very unique. Only Chile can offer this quantity of grapes of this age. The idea is to pay better money and to also involve the whole family and all the different generations, because usually when the farmers, the growers, are dying, the new generation will plant pine, oregano, or eucalyptus, and that is something that we, the wine lovers find is a shame.

The only way is not to pay 10 cents per kilo. It's to pay $1 for the kilo. This way, we now have like 14 different families who are working with us. They're running their vines and we pay them for the grapes and there is a new generation of wine to taste. With the Pipeño wine, we see something very easy, very quiet, with no pretense other than to be consumed as soon as possible. I'd like to say it's an everyday wine for everyday people. It's something very simple and the idea is that the farmers are involved in the wine process, and we try to make the wine with them in their cellars and work together to bottle it. They are paid for the grapes and also for the work they give. Finally, wine becomes something economically good for them.

Your story is a very interesting story. You're French. You've been in Chile for a long time. You probably told this story a million times but let's hear it again. How did you end up in Chile?

Well, I was 22 years old. I was in Paris and I was absolutely lost in what I wanted to do and I had this experience in 1997 in Australia. I said, well, maybe to find myself I have to travel. I decided to leave France and the study I was doing and try to find myself in some way in the world. I started seeing the world, Chile, South America. My idea was to cover all of America from south to north and then go back to Australia. Finally, I stayed here because after three months of parties, I decided that I needed to work to follow my journey. I started working in a restaurant and that's where I connected with wine.

We started making a new wine list. It was 1999. I started tasting many wines. I was very impressed and finally after a year and after tasting Chilean wines, I noticed that all the wines looked quite similar. After four years in Chile, I decided to go back to France after this guy told me that the Mission grape doesn't work for anything. I decided to go back to France to learn to make wine, to try my opportunity with Chilean Mission grapes.

You learned how to make wine in France, and then you were compelled to come back to Chile?

My idea was to go to France and learn first of all if I am able to make wine, because it seemed like maybe it was just a fantasy in some way. When I went back to France, I discovered that there are many types of ways to make wine. In this industry there is industrial, semi-industrial, non-industrial and totally traditional. I prefer the more traditional way. I learned in Burgundy and I worked with some companies in Burgundy because I wanted to know if I would be able to be a wine producer, not just a winemaker.

Even if after 10 years, I started to be more of a winemaker than a wine grower, it's only because I don't have any place in Chilean wine. My favorite job in the process is to prune. The moments of sensitivity, the effort, and when you have to prune in winter with the freeze, and when you look back on your line, you can see all the jobs you've done and some days you have worked a lot, and some days you have not. I prefer my evolution brings me more towards the wine process, the winemaking, which I like. But I think it's just a translation to become a wine producer, a wine grower because I think the vine is something really, really sensitive and really, really nice and really, really difficult to grow.

In Chile it's not difficult, in Chile it's easy. You don't have the diseases and infections that are more prevalent in Europe. This combination of events gave me this approach to try to make easy and simple wines with some small and very humble producers. What I've read from wine producers who are my models in Europe is that wine has to be good anytime you open the bottle. I'd have to say that many times, I have seen bottles that are not good or not as good as I had expected. There are many things in the wine process that you need to manage and to survey, but I think everything starts in the vineyard.

How is the terroir in Chile in Bío Bío?

You have many different types of terroir. Here where we are now, it's not an old terroir. It was planted 20 years ago and it's very rich with many organic things. It is something like 12 or 13 percent organic soil. It's very rich, maybe too rich. That's why we try to prune and make some very sensitive wines because there are no problems for the grapes to grow. It's organic culture. Few vines have been planted in this area in these kinds of soils. Traditionally, the Chileans and the Spanish looked for a while to plant in small hills and in infertile soils as they were doing in Europe at this time 500 or 1000 years ago. These kinds of soils that are rich were for potatoes or crops or anything other than vines.

You have mostly granitic soils, rock and many clays. The soils come from red granite, it means a lot of manganese, a lot of iron in the soils, to yellow clay. You have different steps to that. As I said before, we also have places where on the top of this granitic clay you have sand, many sands, all volcanic, all from the sea coast, and you have also some pisara which is slate. You have some soils with slate, but it's in the sea coast area. That makes it different than in other places.

When the revolution of wine happened in Chile in the 1990s, the industry planted where it was easy. Now, they need to have more of an identity so they are going south to source some grapes. They pick some Mission, they also pick some Cinsault. They also have the Carignan. It's like everybody is coming back to the roots in a way, like looking forward to have more identity in the wines than only Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay.

It's very exciting to be here now because in this region, there are many, many different small producers who are able to make good wines and they are starting to be recognized. That's why we are, I don't know, 40 small producers who are exporting more. There was nobody five years ago, like maybe two or three. There is a weight in front of the industry which is this large and big producer with a large plantation. They also are coming here from Casablanca to pick up some grapes from this area to make wine because there is a market for this kind of wine. Right now, you have Miguel Torres, Concha y Toro, and many other people who are making wines with Mission grapes. Nobody was doing that five years ago except this vineyard here, Villa Chillán. Nobody was doing it because it was like, "No way." Now, the markets have asked for it. There is a change.

What do you see as the challenges for the Chilean wine industry right now?

I don't know. There are many things that we can improve or we can challenge in Chile. My project is mostly about telling people that the people who are from Chile understand the Chilean farmers I'm working with. They have to understand that they are able to make good wines and fine wines, that's why I am trying to make the wines as they always have done them, taking them to the customer's market where I'm traveling, and I am lucky because I'm coming from Europe. I was in Copenhagen, I was in London, Hamburg, Japan and the States, and my customers always look for something simple with identity and with emotions.

I think the most important challenge for the small producers is that they have to understand that their wines are great wines and they have opportunities in the market. All the same, as the big name companies with all the marketing created some opportunities, but now markets are open to taste wines that are not branded names, they look for wines with emotion and good average price.

For More information on Louis-Antoine Luyt watch the video on Louis Dressner's website.

Also listen to the I'll Drink to That Podcast.

Buy wine from Louis-Antoine Luyt at Flatiron Wines.