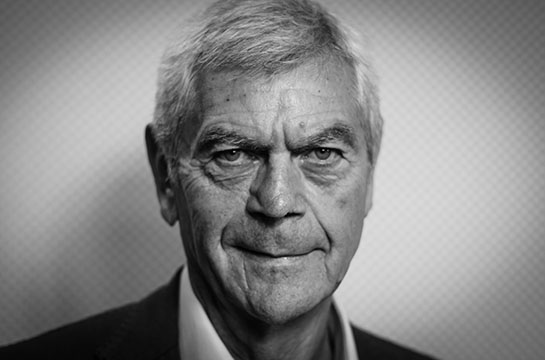

Michel Laroche has been a great promoter of the Chablis region and is one of its key figures. Jane Anson in Decanter described him: "It’s no exaggeration to say that Michel Laroche is defined by Chablis in the same way that Michel Chapoutier is by the northern Rhône, or Olivier Humbrecht by Alsace."

Laroche's entrepreneurial spirit has seen him transform the family business which has become one of Chablis most important estates. He also expanded the family business into South Africa and Chile and into a hotel and wine bar in Chablis. He is also well known for his controversial advocacy of screwcaps.

In 2010, Laroche sold the family estate Domaine Laroche which at the time incorporated over 100 hectares in Chablis as well as the two foreign properties. He kept his favorite parcels which were original vineyards he inherited from his father and created a new venture, Le Domaine d’Henri. The estate lies on Chablis' signature terroir Kimmeridgian stratum of clay-limestone soils which contributes to the signature minerality of Chablis Chardonnay.

Grape Collective talks with Michel Laroche about his new venture and the beauty of Chablis.

Christopher Barnes: So how long has your family been making wine and in Chablis?

Christopher Barnes: So how long has your family been making wine and in Chablis?

Michel Laroche: I was born between two barrels. No, seriously, I'm the fifth generation but in fact there was some Laroche producing wine since the end of the 17th century, so a very long time. They used to be very small producers, having only very few stocks. It is really my great-grandfather, Jean-Victor Laroche, who in 1850, really started to be the first grower with maybe one hectare. When my grandfather passed, he had something like two hectares and at the end of his life my father had about six.

How has winemaking changed over time?

It has changed very much, very much. When I remember being a child, the cellars were full of small barrels called feuillet, 132 liters. If we were producing Chablis today in this kind of barrel, you would be very surprised by it. It was the start of the wine, very much oxidized, dark color. A style of wine my grandfather remembered when I was a child, he enjoyed when the wine was like gold. Which is not at all today very much in taste. It was going very well with the food at that time. When you were having snails, strong butter-sauce, oxidized wine, that all went well. But today with the food which is much more sophisticated, which has a higher quality of the rural material and freshness of the ingredients, I believe it would be a bit difficult for this style of wine.

People would have difficulty associating it with Chablis as they know it today.

Yes sure, sure! Because it was not the same food.

For somebody who is not familiar at all with Chablis, how would you describe it? How would you describe the region and the wine?

I believe the first thing to understand is the geographical location of Chablis. When you are in Chablis, with only 50 km you get to the first vineyard of Champagne. So to me, the style of the wine that we produce in Chablis is more related to Champagne than it is to Burgundy. Keep that in mind. And then we are looking for wine with freshness, elegance. So, what we call the mineral character, with strong acidity, solid backbones, having saltiness at the end. This is what describes Chablis, to me.

So, how would you describe the terroir in Chablis?

You know, there is something very famous in Chablis, which is the Kimmeridgian soil. Very typical of the region. This is a brand of clay with small oyster shells that are about 5-10 mm long, and they are dating back 150 million years. This is very characteristic of the Chablis soil. So, we have enough clay to hold the water when the weather is very dry. But also it's the very stony and deep slopes that make for good drainage. That's the way you can get fruit of good quality every year.

And Chablis is known for being a very, very crisp, mineral version of Chardonnay. And if you compare it to California Chardonnay, it's almost like they're completely different animals.

And Chablis is known for being a very, very crisp, mineral version of Chardonnay. And if you compare it to California Chardonnay, it's almost like they're completely different animals.

They are almost different animals. I fully agree. You know, because climate is the most important point. It's always, in my opinion, when you play on the edge that you get the best results. Chardonnay, the most northern Chardonnay as a still wine, is a Chablis. Then, the next step is Champagne, and they had to put bubbles to make it good and drinkable, because this is the limit for the ripeness. It's always how you get the most interesting things. When, in California, like in the South of France, like all the countries of the New World, you have plenty of sun. It's a completely different story. You know, you make something generous, round and big. Not talking about finesse, elegance, lightness.

The climate in Chablis can be very challenging in certain years. How does that reflect in the wines that you make?

I used to also produce wine in the New World. I know very much the difference. You can see in the New World, almost every year you produce the same style of wine. When you are, when you play on the edge, as I said, then it's much more challenging. Some vintages, you know it's late ripening, it's difficult to get the fruit ripe. It's big variation from one vintage to another. We had '15 very generous, very open, early ripening. We started on the 7th of September, when '14 was high in acidity. Beautiful vintage, but high in acidity. It's completely different profiles.

Then you had hail.

Then you had hail.

That was last year. You know, '16, disaster. Frost. Lot of vineyard, a quarter of the vineyard was frozen. Then another quarter got terrible hail, destroying completely the crop. And then for the rest we had the mildew that developed everywhere. So at the end we produced a quarter of a crop. 13 hectoliters per acre. This is not much. And again, not last week but the week before, we had frost in Chablis. Very severe frost. And Chablis has already lost 50% of its crop.

Challenging years, you know? We thought the period of time where the vineyard was frozen were over, but it's not at all the case. It's still there. Last two years, wow. Challenging.

It's gotta be very difficult as a business to..

It's difficult as a business, because we won't have enough wine. And we have to say to all of our customers, "Last year we gave you a thousand bottles. This year it's going to be only 600 or 500, I don't know." But we cannot sell the wine that we did not produce.

How would you describe your philosophy of winemaking and viticulture?

Yes, this is important because you say, "winemaking and viticulture." I would say viticulture and winemaking. In my opinion, viticulture is certainly 75% of the quality of the final product. When vinification is the last quarter. Indeed, it's important. I mean the quality of the fruit, the quality of the raw material is absolutely key. We are very much organic-orientated. We cannot be 100% organic on each vintage, but we were fully organic in '12. 100% organic in '14 and '15. '13, '16, we had in June to make another treatment because there was so much rain in the spring that we were taking a big risk. And even with that, last year the mildew was already too late when we did it, and the mildew spread everywhere.

I tell you, vinification, the quality of the fruits that you get is absolutely key. We don't use any weed-killer. We only use, we cultivate the soil. Not any chemical fertilizer. We use the natural yeast from the vineyard. We pick them by hand. We sort the fruit, we take all the efforts to produce, if possible, the best possible wine.

And how about the winemaking?

And how about the winemaking?

Winemaking? You have to be involved when you are a winemaker. You don't decide, you're just checking everything is naturally going well. That's the only thing you do. If you have a winemaker, you put your juice here, it comes three months later. And you don't know what you get, because there can be some sugar left. Or you can have the volatile acidities that prosper. So this is the role of the winemaker. To check, and to analyze, and to taste. At first, during the first period of the fermentation we taste every tank, every day. Because you know, it's like your children and you want to check how they go.

What are the differences between the different cuvees that you make?

Differences. We have two labels, in fact, at Le Domaine D'Henri. We have the Le Domaine D'Henri label, which is for the top quality that we produce with this vineyard, the best location. This is partly barrel fermented, and partly stainless steel tank fermented. When we have another label, that we call Les Allées du Domaine, that we use for our youngest vineyard. Or, if we are not 100% with one of the cuvees, the other one, we wait to use this label. We use it as the Bordeaux chateaux do with the second label. That's what we do.

So, Le Domaine d'Henri is a new estate, and you had sold you family estate. How did all that come to pass?

So, Le Domaine d'Henri is a new estate, and you had sold you family estate. How did all that come to pass?

As I said, we are a new domaine, because we started in 2012. A new domaine was an old vineyard, because as an average every vineyard is 35 years old. And I've been producing Chablis for 50 years, you know? So, I created the Domaine Laroche. I developed it completely. But after 42 years, with 200 people, I listed the company on the stock exchange in Paris. I said, "Phew, I would like to have some time for myself." And I only kept 20 hectares that were my property, it was coming my parents from vineyards that I had that were leased to the Domaine Laroche. I took those vineyard back, you know? I called it by the name Domaine D'Henri, simply because the part of the vineyard, all the vineyards were the property of my father, Henri. And Le Domaine D'Henri today is from my parents and I will pass it to my daughters, because I work with my two daughters. It's a small family domaine. Nine people all together. You know, it's completely different. It's not like Laroche that was producing millions of bottles.

And are the wines different?

I think so. In the past I was traveling 1/4 of my time and the rest of the time I was in charge of so many things. Maybe twice a year I was able to visit the vineyard. Now I can do it every week. Every week I take my car and I make my little tour. It takes me three hours. I go to each vineyard. I take my notes, I talk with the guys who work in the vineyard. That's so important, because the fruit is absolutely key. You have to stop to get good fruit for it, if not, nobody can make top wines.