Thinking back to the first week of February seems like a lifetime ago. It was business as usual in New York City and a contingent of 200+ winemakers from Piedmont were in town for the “Barolo and Barbaresco World Opening,” a grand tasting of the region’s top wines. During the event, Grape Collective sat down to chat with Matteo Ascheri, President of the Consortium for Barolo, Barbaresco, Alba, Langhe, and Dogliani wines. Ascheri is the sixth generation winemaker of his family’s winery, Azienda Agricola Ascheri, established in the hills of Piedmont in 1880.

Since our interview, Italy has been hit particularly hard with the coronavirus. We checked back in with Ascheri this week to see how the winemakers of Piedmont are handling the crisis. Lisa Denning: With the entire country of Italy in lockdown, how are the wine producers of Piedmont being affected and how are they coping?

Lisa Denning: With the entire country of Italy in lockdown, how are the wine producers of Piedmont being affected and how are they coping?

Matteo Ascheri: The COVID-19 pandemic has hit hard on Italy and has especially impacted some of our most important sectors: tourism and hospitality. It will take time to recover and go back to ‘business as usual.' Our wineries are coping well despite the lack of cellar visits. Producers are taking advantage of this forced slow time to plan, organize, and supervise the work in the cellar and in the vineyards. They are doing everything they cannot normally do because of the frequent traveling usually required. Restaurant and bar closures worldwide is obviously a serious problem for our industry but what we have noticed so far is that people have increased their wine consumption at home due to the lockdown. This is, of course, good news for online retailers and wineries that can ship directly to consumers or set up their own e-commerce. As with every crisis, there are and will be opportunities. We are carefully planning our activities and strategy for the upcoming months to make sure we make the right choices for when the pandemic ends.

Following is our conversation with Ascheri, focusing on Barolo and Barbaresco, at the World Opening in NYC on February 4, 2020.

Barolo is one of Italy’s most famous wines. How did that happen?

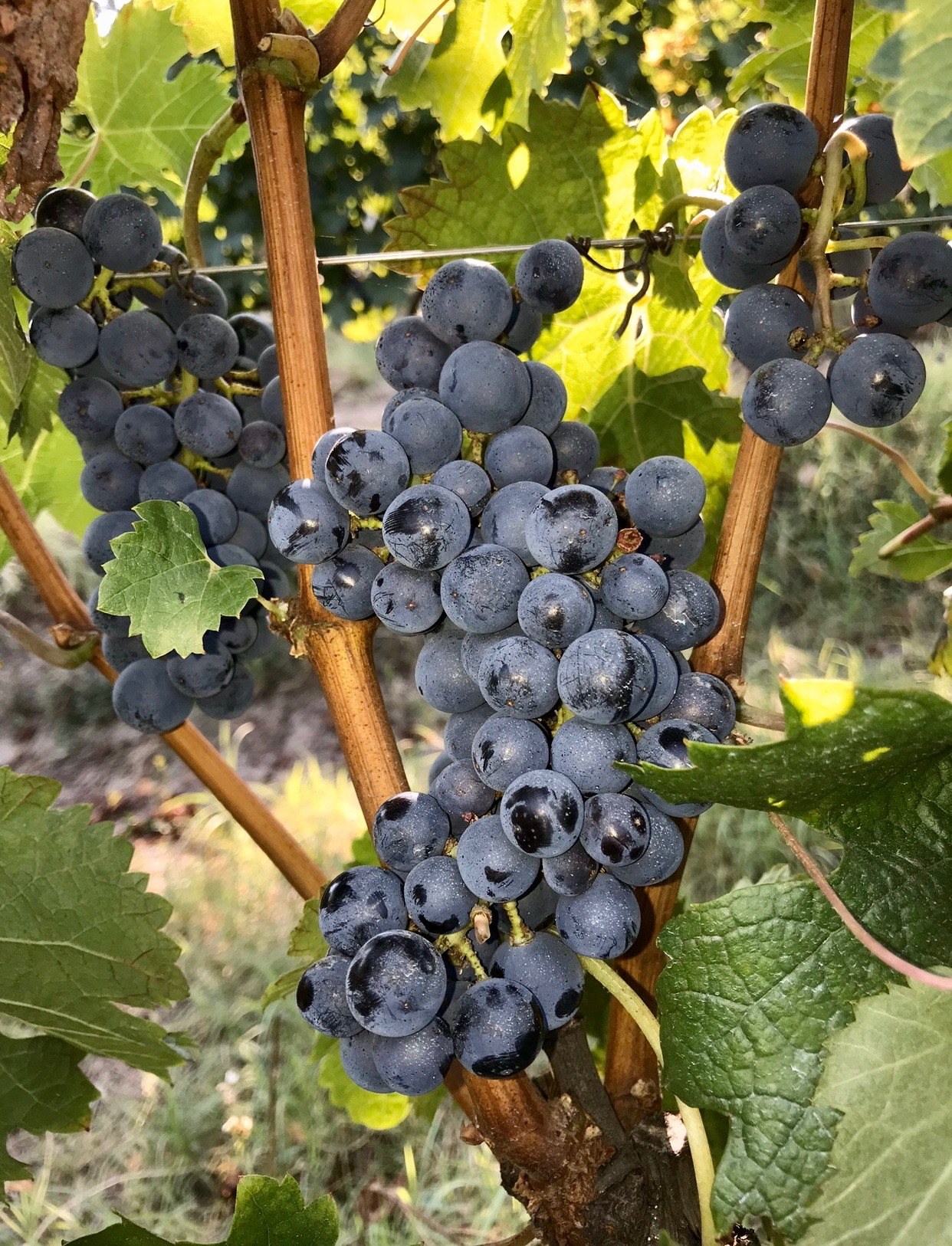

It's a special wine indeed. It's made from a special grape variety, Nebbiolo, a unique grape. To produce a great red wine, everywhere in the world, you need a great red variety. Nebbiolo is one of them and it has a specific character. So everything starts from this variety, it’s the most important thing.

Second, it’s the specific micro-climate, the soil that the grapes will grow in. And third could be the most important, family businesses. Small wineries. So you get personal interpretation, and unique things. Then at the end if we are to describe Barolo, it is not an easy wine. You cannot approach wine starting from Barolo, for instance, because you need a certain experience. But when you reach Barolo, you will see that it is elegant, refined and powerful. So that is what makes this wine unique.

You mention the small family businesses. In recent years, there's been an influx of foreign investment to Barolo. Do you feel that it is changing the character of the area?

This is changing our future. I'm not sure if it is good or bad. Of course if you have to sell your own land, it's positive because you have more money. But at the end, it's not positive for the local wineries if they cannot buy these vineyards themselves because the cost is so high. At the end, we hope it is not changing too much. Because the most important part, as I told you, is the personal touch, a unique identity, and we cannot permit somebody else to change our destiny.

What about people who are young and want to start in the business? Can they even afford to nowadays?

Starting is very iffy because you need a lot of money, so it's difficult to start. Normally the families are long-time established in our area. The problem isn't just to start, it’s that you need an incredible amount of money. It’s a huge investment that has a return very late in years so it is something that is difficult to start. It’s almost impossible. So it's a family's heritage, for a new generation in the family. Being a young person, it would be too difficult unless they are a very rich kid, of course. Otherwise it's difficult to start. Can you tell me what the main differences between the Barolo and Barbaresco regions are.

Can you tell me what the main differences between the Barolo and Barbaresco regions are.

It's interesting, because it's the same variety at the end, nebbiolo. What changes is the area of production. Barbaresco is a little bit farther north, compared to Barolo. The climate is basically similar. Let's say Barbaresco is more elegant, to make it easier to understand, compared to Barolo. Barolo takess a longer time to settle. It has much more complexity. At the end, they are two great expressions of the same grape variety. There can be significant differences but sometimes not so big.

Is it mostly because of differences in the soil?

Yes. Soil, and as a consequence, the rules of production. Barolo has a minimum aging of four years, Barbaresco has three. It is one year less, but the main thing is that the grape variety is exactly the same. What changes is the soil, not in a dramatic way, but it makes sense for us. And then of course the rules of production that are established by the producers. The rules of production of the wine are not made by the government. They are made by the producers themselves. So the producers decide how to produce their own wines. Then too, they create a rule. To produce the wine, you have to respect these rules. But Barolo and Barbaresco are exactly two different expressions, slightly different, of the same grape variety.

People talk about the traditional versus the modern style. Can you tell us what those differences are?

This is something that goes back to the '70s and went on for about 25 years. There were cultural battles between the people producing wine in the very traditional way without moving one inch forward and those who wanted to try new ways to produce wine.

So it was traditional up until the 1970s?

Yes. The battle started at the end of the '70s. Before this period, the area, the economy was divided in this way. A few wineries were basically buying the grapes from farmers and producing wine. In terms of producing Barolo anyways. And on the other side were the farmers. There was a huge crisis at the end of the '70s when the market of the grape was really down. There were producers of grapes who weren't trying to sell their own grapes. Grape is fresh fruit, so if you're not selling it today, it's not good and they were forced to produce their own wine, to be out of the problem of the market of the grapes. So the new producers, they started to introduce new techniques to help make the wine ready to sell without aging it for so long. These were the modernists. The region was stuck. So this was the big battle.

But the result is that after 25 years, the traditionalists understood that they had to move forward. They had the big pressure from the modernists, so they introduced better techniques, better ways to produce the wine, better vineyard management. At the same time, the modernists, they understood that they went too far. That at the end, was not just to produce a great wine. But to [inaudible 00:06:52] you could recognize, and they went back. So nowadays, everything is much more in the middle but the result is the great wine that in a great sense today is the result of this harsh, hard battle. It was technique but also culture. But this made people evolve from their own position. And the revolution was not traditionalists for modernity. And the modernists, they went back because they understood that rules are the most important thing and you have to honor or at least recognize that.

So it sounds like it's at a good point now.

It's at an extremely good point because this was a big battle with a lot of discussion and the final result is absolutely positive for everybody. Without this pressure, without these changes, the revolution that you can taste today would not be possible. Since Barolo and Barbaresco are often compared to Burgundy, do you ever envision a hierarchical classification system of the growing areas, the MGAs, of Barolo and Barbaresco that would be similar to the Premier and Grand Cru classification of Burgundy?

Since Barolo and Barbaresco are often compared to Burgundy, do you ever envision a hierarchical classification system of the growing areas, the MGAs, of Barolo and Barbaresco that would be similar to the Premier and Grand Cru classification of Burgundy?

There are indeed a lot of similarities between the two areas, but the historical evolution is very different. The Burgundy classification system dates back to the 19th century, while ours is much more recent, beginning in the 2000s. Classification on quality was much easier at that time (19th century) without the excessive economical interests, while today this is almost impossible to do. Who will decide and based on what? History can be a good way but things change constantly. It will be easier, simpler and more effective if it will be the market itself, at the end, that classifies the single vineyards of the Barolo and Barbaresco area according their quality. Moreover each area has is own identity and it’s not easy to repeat the same outline everywhere. I know that this can be very confusing for everybody and, above all, for the consumers, but it can be more interesting too.

Let's talk about organic viticulture. Are you seeing more consumer demand for it?

Yes, of course.

Why aren't there more producers making organic wines in your area?

That is a good point and I believe it is absolutely important that we will have more and more involvement in these issues. Sooner or later, we are going to be out of these stereotyped concepts that are linked to ideological points of view like sustainable, organic, and biodynamic agriculture. We (as winegrowers) are the first ones that would like to reduce the amount of pesticides and to reduce the chemical approach because we handle these products and we would like to take care of our our health.

But probably the approach is much more complicated than just saying yes or no to the use of certain products. Sometimes it is good to be organic, but the right chemical can help a lot too. If you're organic, it means, at the end, that you are using much more fuel, much more water, so your impact is much higher than you think. Everything is linked to better knowledge, to understand the best way to reduce our impact on the environment, on nature. To do this, we are deeply involved in the research because this is the only way to improve, but there is probably not just one solution. There is a mix of solutions that can be sourced in one of the different approaches we may have (sustainable, organic, and biodynamic). The most important thing is to work without ideological or commercial approaches because we have to say that some kinds of positions are used in a commercial way, just checking facts to try and improve our position.

Is it partly because of the weather, the humidity, that makes organic viticulture difficult?

Of course, everything is linked to the weather conditions. On the other side, as an extreme concept, organic production could be an approach made by rich people (that don’t need to produce too much to live) for rich consumers (that can afford to pay a lot for a product). Of course this can be positive, but we have to consider all the customers who have less possibilities. So we have to be out of this way of thinking. Sustainability, organics, biodynamics have to be considered together in order to find the best solution for all.

Today, with social media, there’s a new culture of marketing. How are you reaching out to your customers in ways that you haven't in the past?

You are talking to the wrong person, because I don't do all the social things. I like to say that in a world where communication and words are the most important thing, we like to communicate through what we are doing. Everything that we say to the world, we do. So it's our bottle, our wine — everything is inside of the bottle. It's my personal thinking, of course, so I'm not really boasting to say it, but it's a good approach. And it's part of our culture.