We began to enjoy the taste of wine soon after we met in 1973, but we began to love wine when we discovered its stories. Hugh Johnson’s “The World Atlas of Wine” gave it geographical context. Even more important to us was Leon D. Adams’s “The Wines of America,” which felt like a guided tour of people and history, like this section on Michigan:

“Two more wineries in Paw Paw offer tours and tasting. Next door to Warner on Kalamazoo Street is the million-gallon St. Julian cellar, with a handsome tasting room built since a fire destroyed part of the building in 1971. Mariano Meconi started this winery in 1921 at Windsor, Ontario, as the Italian Wine Company, moved it at Repeal to Detroit, and five years later brought most of its equipment to Paw Paw.”

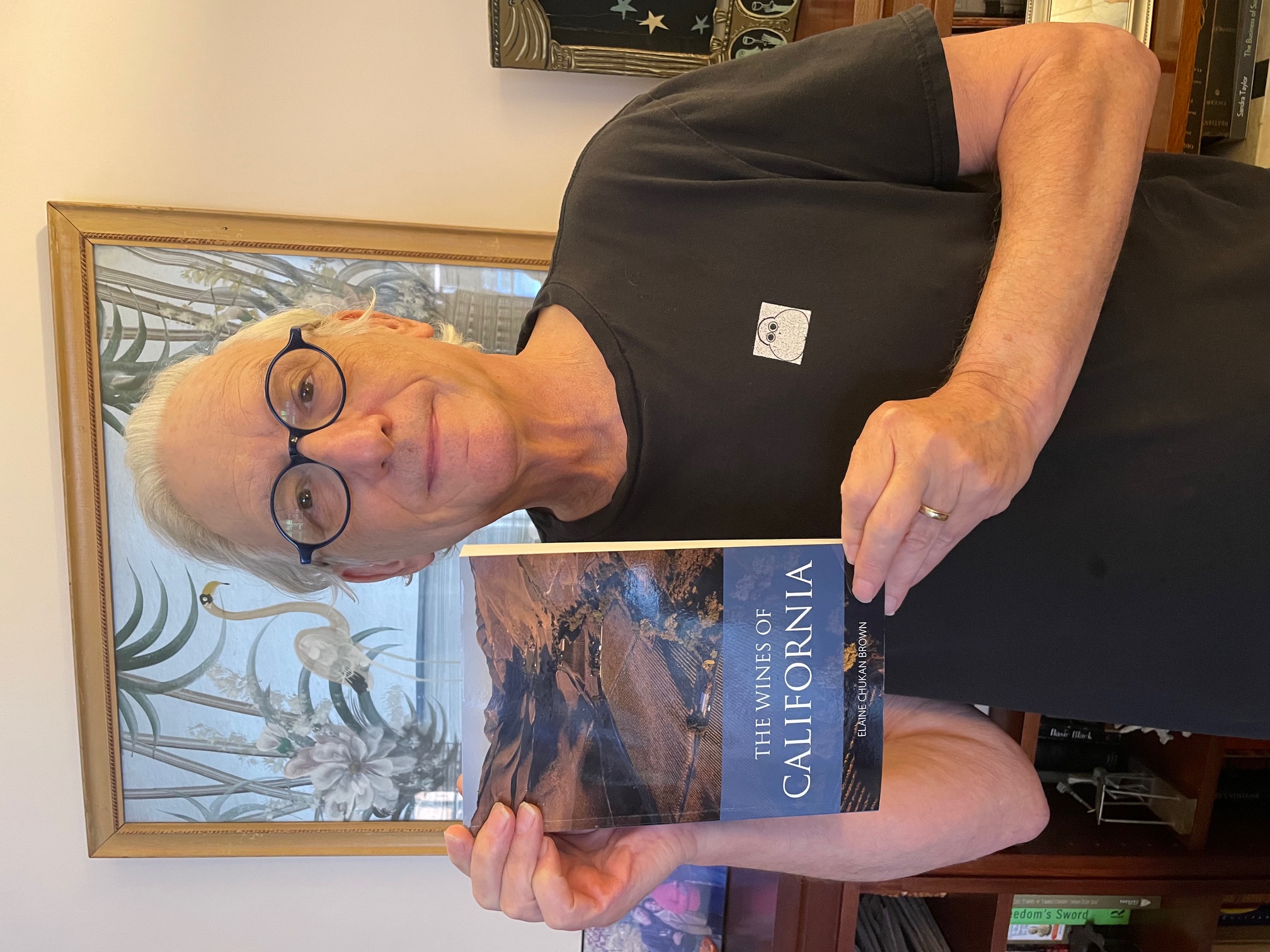

Wine is about history, geography and people. Rarely has a book combined the three more powerfully than “The Wines of California” by Elaine Chukan Brown, from Academie du Vin Library ($44.95 at amazon.com and the publisher). And this book brings something additional, something different, as Brown explains:

Wine is about history, geography and people. Rarely has a book combined the three more powerfully than “The Wines of California” by Elaine Chukan Brown, from Academie du Vin Library ($44.95 at amazon.com and the publisher). And this book brings something additional, something different, as Brown explains:

“In looking at the state’s wine history within a larger context, I have tried to demonstrate the connections between its successes and pivotal challenges, its triumphs and the costs that came from them. This includes acknowledging that its history of winegrowing has depended on the labor of people of color. Other histories on the wine industry have tended to overlook or erase this reality. By incorporating this important part of wine’s development, we can better understand the history of California and perhaps also what solutions for today’s labor issues might be possible.”

The book doesn’t only discuss every wine region of the state in depth, but, in many capsule introductions, includes the first peoples.

Santa Barbara County.

Known for: Pinot Noir, Sideways.

Lesser-known strength: homes to Charlie Chaplin, Oprah Winfrey, and Ronald Reagan.

Leader in: savory Chardonnay, Santa Maria BBQ, pinquito beans.

First peoples: Michumash.

Consider the elegance there of combining humor and education, history and current affairs. That’s a good example of the whole book.

Brown is a highly regarded speaker, writer and educator whom we have known for several years. Brown and Dottie serve on the board of the Wine Writers Symposium at Meadowood, which is sponsored by the Napa Valley Vintners trade organization and Meadowood Napa Valley. At the Symposium in 2023, for a panel called Writing Across Styles, John interviewed Brown about a 793-word masterpiece Brown had written for Wine & Spirits called “Caribou Bones and Burgundy.” Brown is Indigenous – Inupiaq and Unangan-Sugpiaq – from what is now Alaska. As John spoke with Brown about the creation of that article, Brown explained that it really was all about their family and started to cry. Then John started to cry – and then everyone in the whole room cried.

(Elaine Chukan Brown, Dottie, and sommelier, Miguel de Leon)

(Elaine Chukan Brown, Dottie, and sommelier, Miguel de Leon)

The book is dedicated to Brown’s daughter, Ellaita, and “For Dottie, who did it first.” So we would not pretend for a minute that what you are reading here is objective. But it is true.

This book is core, essential. For anyone just beginning their journey, this will put wine in context in straightforward language with little jargon. For example: Cabernet Sauvignon’s “move into the steep slopes and mountain ridges of the state brought recognition of mountain tannins. While there are high elevation Cabernet vineyards elsewhere in the world, nowhere else is there a high enough concentration of them to create the notion of a mountain Cabernet.”

Like Karen MacNeil’s “The Wine Bible” and Jancis Robinson’s “The Oxford Companion to Wine,” this book needs to be on the shelf as a reference. For those who want more structured learning about wine, there’s Kevin Zraly’s “Windows on the World Complete Wine Course,” which celebrated its 35th anniversary edition in 2020.

Those of us far along on our journeys will find all sorts of interesting material, too. We thought an American Viticultural Area was primarily a defined geographical place of origin. Turns out it’s more than that: “The Mendocino Ridge AVA only takes in vines grown at 1,200 feet (366 meters) and...

Wine is about history, geography and people. Rarely has a book combined the three more powerfully than “The Wines of California” by Elaine Chukan Brown, from Academie du Vin Library ($44.95 at

Wine is about history, geography and people. Rarely has a book combined the three more powerfully than “The Wines of California” by Elaine Chukan Brown, from Academie du Vin Library ($44.95 at