Lamberto Frescobaldi thinks long term – really, really long term. He is the 30th generation of one of Italy’s most storied winemakers, with prominent family roots going back more than 700 years in many endeavors -- economic, political, cultural. So when Frescobaldi, president of his family’s company, Marchesi de' Frescobaldi, plants its first flag in the U.S. – specifically, at a small winery in Oregon – it’s worth taking special note. Why did he do this? And why not Napa?

We had dinner recently with Frescobaldi and Marco Balsimelli, who has been technical director of Frescobaldi’s Super Tuscan wine, Ornellaia, for two years. Balsimelli is Italian but has spent a large part of his career in Bordeaux. We were there to taste the new releases, the 2022 Ornellaia Superiore and the Ornellaia Bianco 2022, along with the 2001 Ornellaia Superiore, a super rare treat; all Bolgheri DOCs.

We had dinner recently with Frescobaldi and Marco Balsimelli, who has been technical director of Frescobaldi’s Super Tuscan wine, Ornellaia, for two years. Balsimelli is Italian but has spent a large part of his career in Bordeaux. We were there to taste the new releases, the 2022 Ornellaia Superiore and the Ornellaia Bianco 2022, along with the 2001 Ornellaia Superiore, a super rare treat; all Bolgheri DOCs.

(Lamberto Frescobaldi (right) and Marco Balsimelli, technical director of Frescobaldi’s Super Tuscan wine, Ornellaia)

Ornellaia, which is on the Tuscan coast with its Mediterranean influences near Bolgheri, has a complex history. It was founded in 1981 by Marchese Lodovico Antinori as part of the Super Tuscan movement, went through ownership changes and was fully acquired by the Frescobaldi family in 2005. The flagship Superiore is a Bordeaux blend, considered an Italian grand vin or first growth, and expensive: The 2022 Superiore is $310 and the Bianco, which was first made in 2013 and regarded as a grand cru, is $280.

Frescobaldi, 61, is also president of the Unione Italiana Vini, the Italian winegrowers’ association. Dottie interviewed him in 2017 about a project he leads on the penal colony on Gorgona Island, off the coast of Tuscany, in which prisoners make commercial quantities of wine as a way to prepare for employment after confinement. He said the project is still going strong and the prison continues to have a very low recidivism rate. Here are five takeaways from our discussion:

--On Oregon. “I was going to Napa for years to look for something and it was never right and the more I was waiting, the more expensive it was becoming. The payback was always around the year 3257. We are 30th generation, but if we need to wait another 30 generations to pay it back, forget it.” And some of Napa wines were not to his taste anyway. “There was a moment where they became too muscular but at the same time very sweet on the palate – big muscles, very small brains. It happens when you go to the gym too much.”

He found the people of Oregon charming and welcoming, “authentic” and down to earth. He added quickly that he also found the folks in Napa to be nice but he said he fell “in love at first sight” with Domaine Roy et Fils, a 40-acre winery in the Willamette Valley, and bought the winery two years ago. He likes the laid-back vibe of the region, but only to a point. When he first visited the cellar, there was a ping-pong table. That’s gone now, and Frescobaldi anticipates replacing much of the winery’s machinery. He is looking for more “precision” and has brought in his own winemaking team, although the former owner, who lives in Montreal, still has a stake. “I said to him, look, would you be so kind to remain with a small share and he said, ‘I'd be more than happy.’ So he has a share of the winery and is still connected and that’s great,” Frescobaldi told us.

The winery mostly produces Pinot Noir and Frescobaldi expects that to continue. He admires the supple fruitiness of Oregon Pinot Noir and would like to accentuate that. He is fond of Pinot Noir because his family’s Pomino winery, in the Florentine mountains where his great-grandmother lived, specializes in Pinot Nero. Frescobaldi anticipates planting more acreage in Oregon.

--On that white “blend.” We knew that the elegant white, Ornellaia Bianco DOC, was primarily Sauvignon Blanc, with hints of tangy mangoes and white peaches and earthy minerality. But it had a depth and complexity and savory quality that made us wonder if it had been blended with another grape so we asked. “It is a blend -- of Sauvignon Blanc and Sauvignon Blanc,” he said with a big smile. He continued: “That could be a joke but it’s not a joke. How many harvests [of those grapes] do you have? You are picking a little bit earlier, a little bit in-between, a little bit later. So it’s the same grape variety, but you are not going to pick one day and that’s it. It’s bits and pieces, different pieces and also even in the same plot, but picking in different moments of the season.”

Balsimelli said it is made in oak, “30% new, and the rest is used barrels. But the toast side is really, really well integrated. We work a lot to find the right forest, the right toast and we work a lot together to find the best solution for us to respect the grapes.

Balsimelli said it is made in oak, “30% new, and the rest is used barrels. But the toast side is really, really well integrated. We work a lot to find the right forest, the right toast and we work a lot together to find the best solution for us to respect the grapes.

(2022 Ornellaia Bianco, a "blend" of 100 percent Sauvignon Blanc)

“The vines are older and older so the result is better now than compared maybe with the first Ornellaia Bianco. The style has evolved a little bit thanks to the age of the vines,” he added, explaining that the average age of the vines is 20 to 25 years.

But, we asked Frescobaldi, didn’t they blend in just a bit of Viognier for a couple of years? His response was more philosophical than we expected: “Sometimes you are looking for something, searching for something, and you don’t know what you’re looking for. So sometimes you look for new roads, new ventures, but then when you start blending you don’t really know where you are. You tend to like what you’re doing in that moment, but sometimes you don’t perceive where you’re going and you start mumbling around the world and searching for who knows what. So there is a moment, between midnight and one o’clock in the morning, where you ask yourself where am I going?”

After we all took a few beats, wine publicist Paul Yanon, of Colangelo & Partners, which set up the tasting asked, “Are we still talking about wine?”

Bottom line: They dropped the Viognier.

--On the most exciting moment of the year. Balsimelli said that, to him, the most exciting moment of the year was around the time we were speaking, in March. Why? Because the Ornellaia Superiore blend is made, in effect, from 80 different wines – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot from several plots with differing soils. “We have 42 soil types. In some places the presence of the sand is more important. We have a lot of limestone, which is really important for the acidity and the salinity. Close to the winery we have more clay – clay is really important in this area and the wines are more structured or powerful or dense.

“So after six months in barrel we wait a little bit because sometimes if you do the blend later it is not good because the elements need to be together for the aging. But too soon is not good because sometimes some plots need time to express their character. So I think it’s a good solution to blend after six months. But we take a lot of time. We try to find the best solution possible and the idea is always to express this piece of land in the glass bottle but it’s a beautiful moment.”

--On why Frescobaldi hired Balsimelli all the way from France for this job. The first two words out of his mouth: “He’s humble.” He added: “I strongly believe in life that you definitely have to be educated, but you have to be humble.” Frescobaldi used the same word to explain why he liked the people in Oregon so much. “It's one of those things that we're all servants to Mother Nature at the end of the day,” he said.

--On why Frescobaldi hired Balsimelli all the way from France for this job. The first two words out of his mouth: “He’s humble.” He added: “I strongly believe in life that you definitely have to be educated, but you have to be humble.” Frescobaldi used the same word to explain why he liked the people in Oregon so much. “It's one of those things that we're all servants to Mother Nature at the end of the day,” he said.

(Dottie with Frescobaldi and Balsimelli)

--On challenges facing the wine industry. Frescobaldi’s business is international, so events everywhere affect the company’s sales. He had been to the United Nations before we met with him and he planned to return soon. Economic problems in China, slowdowns in Germany, Covid in Japan – they all have affected the wine business. He noted that the French are drinking less wine and Italy’s crackdown with new penalties on drinking and driving was making restaurants nervous. At the time of the dinner, President Trump had threatened tariffs. Russia had accounted for a nice portion of the company’s sales, but Frescobaldi cut off Russia after it invaded Ukraine. “We have quite a lot of history of managing markets. So what we do is that even though the market is performing very nicely, we never give too much to that market because we do not want to become dependent on it if something happens. So one year you have the war, one year you have the Twin Towers, another time you have Mr. Trump. Russia for us was an amazing market. It was an extremely good market and when the war arrived, we decided not to ship any longer.”

With all of the chatting, we still focused on the wines, of course. The 2022 Rosso was already beautiful, elegant and balanced. To be sure, it has a long life ahead of it, but for such a youngster, it was surprisingly seamless, with great fruit, nice salinity and an undercurrent of minerals. The stunner to us was that the 2001 also tasted very fresh, with a core of ripe fruit that had not diminished in time.

They were delicious. But were they the best wines? One of our favorite comments from Frescobaldi during dinner referred to that. “The best wine of the world has not been made and it will never be made. The best wine of the world doesn’t exist. Since when we are at school and we studied there is the best student and the worst student, so we tend to do that. But I believe that when we talk about wine, there is so much that is going on and there is so much fun behind this world of wine. How long could you enjoy the same wine day after day, even if it is Domaine de la Romanée Conti? After a while you say, wait a second, is there something else out there? And I think that’s what it is all about, what we are doing. Our curiosity has led us to become more demanding in what we’re doing and we’re being really obsessed now with not doing everything as we were.”

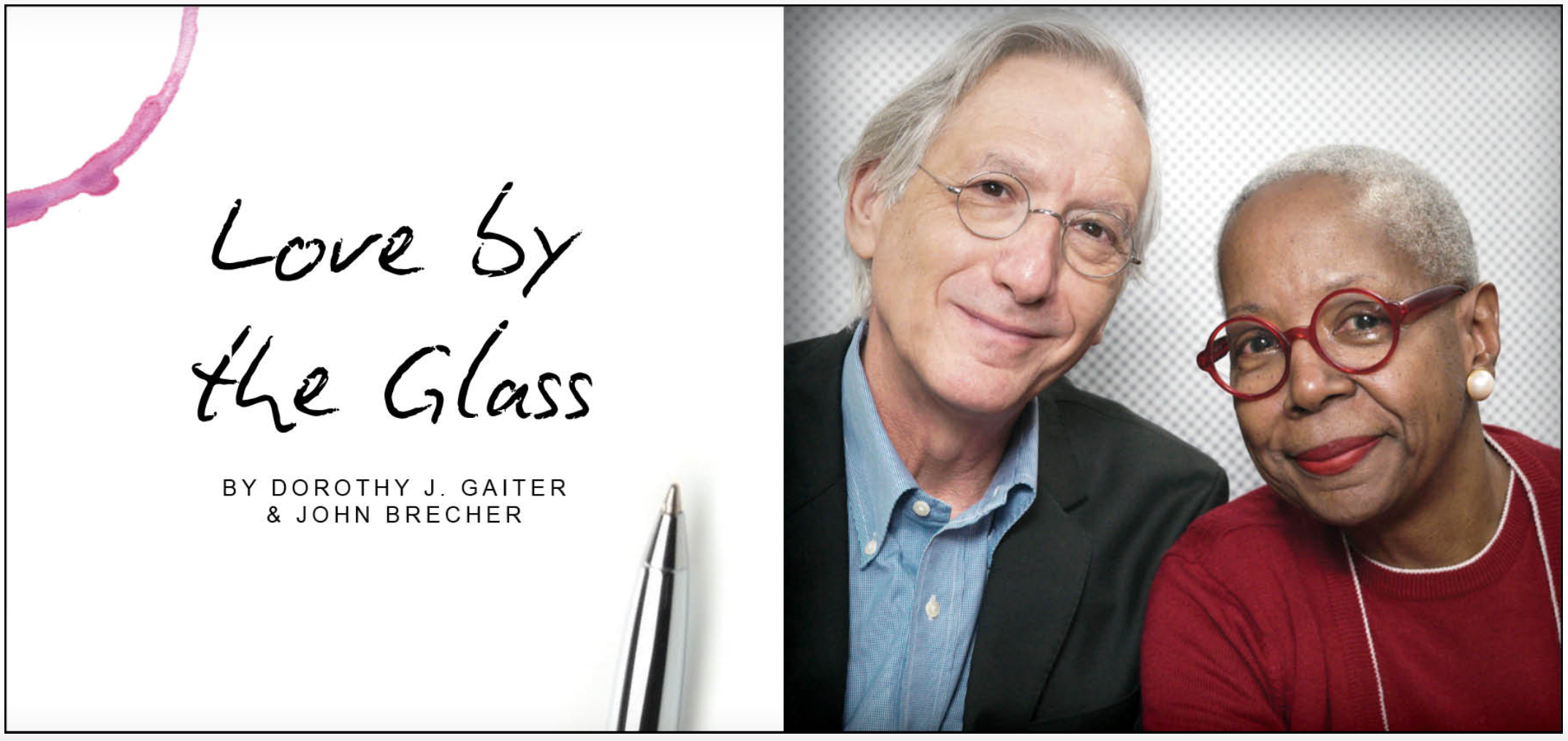

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.