We began to enjoy the taste of wine soon after we met in 1973, but we began to love wine when we discovered its stories. Hugh Johnson’s “The World Atlas of Wine” gave it geographical context. Even more important to us was Leon D. Adams’s “The Wines of America,” which felt like a guided tour of people and history, like this section on Michigan:

“Two more wineries in Paw Paw offer tours and tasting. Next door to Warner on Kalamazoo Street is the million-gallon St. Julian cellar, with a handsome tasting room built since a fire destroyed part of the building in 1971. Mariano Meconi started this winery in 1921 at Windsor, Ontario, as the Italian Wine Company, moved it at Repeal to Detroit, and five years later brought most of its equipment to Paw Paw.”

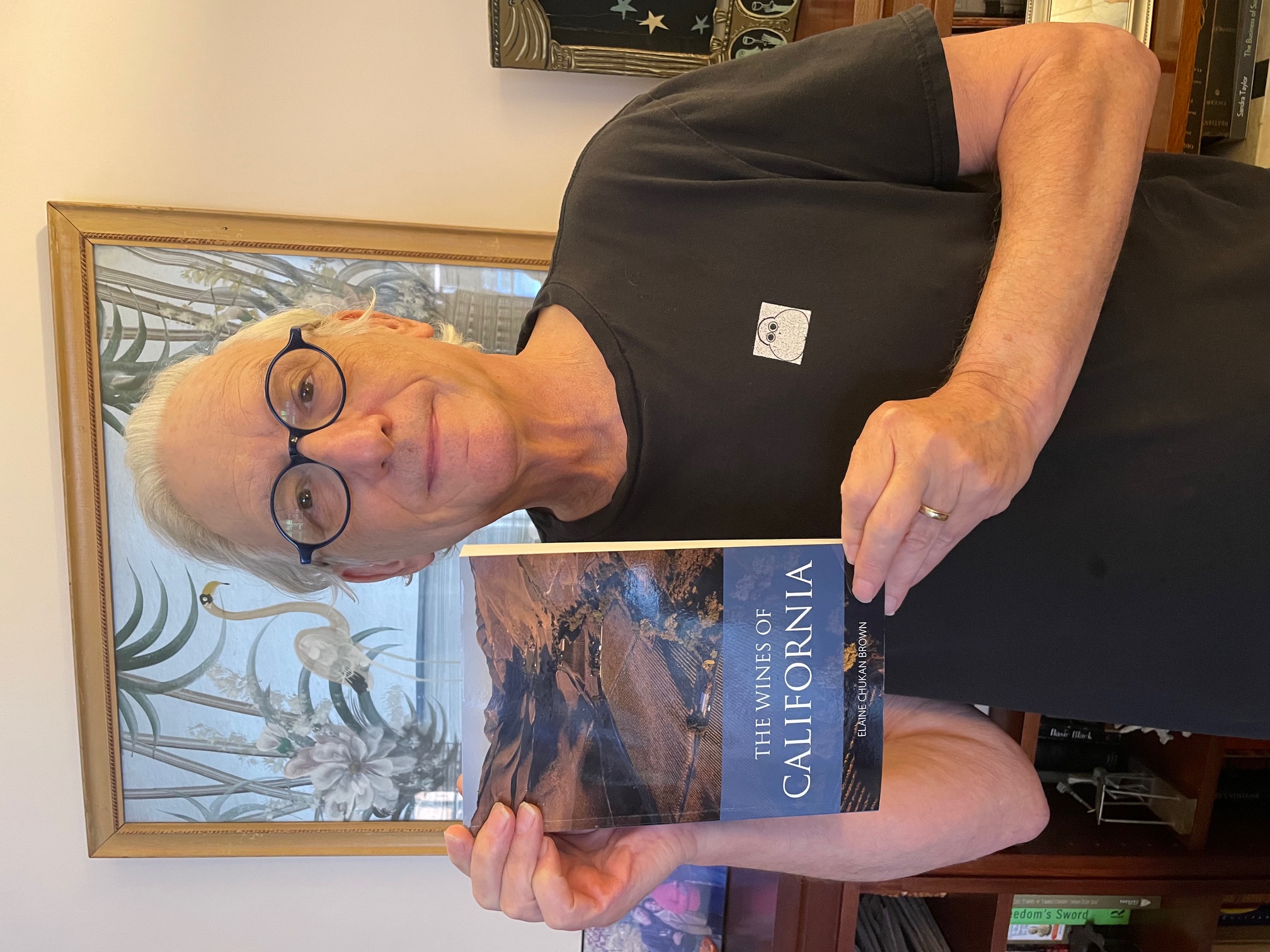

Wine is about history, geography and people. Rarely has a book combined the three more powerfully than “The Wines of California” by Elaine Chukan Brown, from Academie du Vin Library ($44.95 at amazon.com and the publisher). And this book brings something additional, something different, as Brown explains:

Wine is about history, geography and people. Rarely has a book combined the three more powerfully than “The Wines of California” by Elaine Chukan Brown, from Academie du Vin Library ($44.95 at amazon.com and the publisher). And this book brings something additional, something different, as Brown explains:

“In looking at the state’s wine history within a larger context, I have tried to demonstrate the connections between its successes and pivotal challenges, its triumphs and the costs that came from them. This includes acknowledging that its history of winegrowing has depended on the labor of people of color. Other histories on the wine industry have tended to overlook or erase this reality. By incorporating this important part of wine’s development, we can better understand the history of California and perhaps also what solutions for today’s labor issues might be possible.”

The book doesn’t only discuss every wine region of the state in depth, but, in many capsule introductions, includes the first peoples.

Santa Barbara County.

Known for: Pinot Noir, Sideways.

Lesser-known strength: homes to Charlie Chaplin, Oprah Winfrey, and Ronald Reagan.

Leader in: savory Chardonnay, Santa Maria BBQ, pinquito beans.

First peoples: Michumash.

Consider the elegance there of combining humor and education, history and current affairs. That’s a good example of the whole book.

Brown is a highly regarded speaker, writer and educator whom we have known for several years. Brown and Dottie serve on the board of the Wine Writers Symposium at Meadowood, which is sponsored by the Napa Valley Vintners trade organization and Meadowood Napa Valley. At the Symposium in 2023, for a panel called Writing Across Styles, John interviewed Brown about a 793-word masterpiece Brown had written for Wine & Spirits called “Caribou Bones and Burgundy.” Brown is Indigenous – Inupiaq and Unangan-Sugpiaq – from what is now Alaska. As John spoke with Brown about the creation of that article, Brown explained that it really was all about their family and started to cry. Then John started to cry – and then everyone in the whole room cried.

(Elaine Chukan Brown, Dottie, and sommelier, Miguel de Leon)

(Elaine Chukan Brown, Dottie, and sommelier, Miguel de Leon)

The book is dedicated to Brown’s daughter, Ellaita, and “For Dottie, who did it first.” So we would not pretend for a minute that what you are reading here is objective. But it is true.

This book is core, essential. For anyone just beginning their journey, this will put wine in context in straightforward language with little jargon. For example: Cabernet Sauvignon’s “move into the steep slopes and mountain ridges of the state brought recognition of mountain tannins. While there are high elevation Cabernet vineyards elsewhere in the world, nowhere else is there a high enough concentration of them to create the notion of a mountain Cabernet.”

Like Karen MacNeil’s “The Wine Bible” and Jancis Robinson’s “The Oxford Companion to Wine,” this book needs to be on the shelf as a reference. For those who want more structured learning about wine, there’s Kevin Zraly’s “Windows on the World Complete Wine Course,” which celebrated its 35th anniversary edition in 2020.

Those of us far along on our journeys will find all sorts of interesting material, too. We thought an American Viticultural Area was primarily a defined geographical place of origin. Turns out it’s more than that: “The Mendocino Ridge AVA only takes in vines grown at 1,200 feet (366 meters) and above. It’s the only non-contiguous AVA in the United States, circumscribing not a complete area but instead mountain islands within it.”

And while we know about the Petaluma Gap, this explanation is so deep and yet so simple: “One of Sonoma County’s hallmark developments has been recognition of the Petaluma Gap AVA. Named for a low spot in the coastal mountains in the west, the Petaluma Gap is the first AVA in the country to be delineated by wind. Full of fog, and with winds surpassing 8 miles per hour (13 kilometers per hour), the area gives rise to wines that are decidedly structural, textured, and savory.”

And while we know about the Petaluma Gap, this explanation is so deep and yet so simple: “One of Sonoma County’s hallmark developments has been recognition of the Petaluma Gap AVA. Named for a low spot in the coastal mountains in the west, the Petaluma Gap is the first AVA in the country to be delineated by wind. Full of fog, and with winds surpassing 8 miles per hour (13 kilometers per hour), the area gives rise to wines that are decidedly structural, textured, and savory.”

(Elaine addressing symposium participants during an off-site)

Ultimately, though, Brown makes clear that any story about wine is a story about people. Brown introduces the missionaries and the pioneers, like Martin Ray and Warren Winiarski (and their brief, unpleasant working relationship). Brown also explains how The Vice became such a big hit in such a short time and discusses the challenges of families like the Hirsches of Sonoma Coast, whose courage and gambles make for terrific reading. Our colleague Lisa Denning interviewed Brown for her blog, The Wine Chef.

The book is divided into three sections: How We Got Here; Where We Grow; and What We’re Facing. What We’re Facing involves climate change, demographics and sustainability. Ray Isle’s recent book, “The World in a Wineglass,” profiles wineries around the world that are focusing on organic, artisanal and sustainable production and Brown’s last section is a good companion to that. Brown’s second section tells individual stories of regions and their wineries, including quite a few that are small and not well-known. (The “His and Hers” Vermentinos made by Ryan and Megan Glaab of Ryme Cellars in Sonoma County is one of many smiles in the book. Brown writes that the “two different wines each made in the style preferred by either Ryan or Meg is the only example, they tell us, of them disagreeing in wine. The His includes skin contact and a little more aging. The Hers is straight to press and sells a lot more wine.”)

The first section, focusing on how we got here, is required reading for anyone who truly wants to understand California wine because it is history that’s not often told. It’s about gold and water and railroads, of course, but it’s also about people taking advantage of other people, how “Indigenous peoples started California wine” and were eliminated, Mexican people were marginalized and Asian people were used and discarded. Brown tells these stories in a clear way without stridency. The history Brown presents makes it even more astonishing, for instance, that Kitá became the first Native American-owned winery in California in 2010, founded by Chumash people who were once known as Michumash; that wineries owned by Mexican-Americans (like Mi Sueño) are still rare; and that in 1995 Brown Estate became the only Black-owned estate winery in Napa.

So much of the history is ugly and, unfortunately, as Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

So much of the history is ugly and, unfortunately, as Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Ultimately, “The Wines of California” is not just about California. It’s about the kind of people, all over the world, who have created wine as a culture and as an industry – some who got rich and famous from it and many who were disposed.

Brown writes, “California has demonstrated again and again the determination of its people to fight for positive change, even as its history includes innumerable obstacles and harms,” adding: “The important difference in the struggles of history is not whether hardships and harms have happened — they consistently do almost anywhere — but how the region’s communities work to foster positive change. California wine is in yet another era of reinvention.”

We still refer to our 1973 version of “The Wines of America” – not for current information, of course, but to see what some things looked like in real time, like Google Earth timelapse. Brown’s book, in the same way, is both current and timeless.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.