Christopher Bates has taken a circular route home opening Element Winery in the Finger Lakes with his father Bob in 2005. Originally from the Finger Lakes region he worked in the hospitality industry for fifteen years after graduating the Cornell School of Hotel Administration. His stints include General Manager & Executive Chef of Hotel Fauchère, Relais & Chateaux as well as the Inn at Dos Brisas, Relais & Chateaux.

In 2012 Christopher was named Best Young Sommelier in the World after winning Best Young Sommelier in America previously in the year. In 2013 he won the sommelier competition TopSomm. He passed his Master Sommelier Exam in May 2013. In May 2014 Christopher and his wife Isabel opened F.L.X. Wienery a gourmet hotdog and burger joint in the Finger Lakes. Recently they added a second Finger Lakes restaurant, the 12 seating fine dining FLX Table.

This year Bates was named as one of the Food & Wine's 2016 Sommeliers of Year.

Grape Collective talks to Christopher Bates about the potential of the Finger Lakes, burgers and cracking the MS exam.

Christopher Barnes: Christopher, tell us a little bit about the history of the Finger Lakes as a wine growing region.

Christopher Bates: Of course. The history of the Finger Lakes itself is a really long one. We've had crops and farming really as a staple here for a very, very long time. Grape farming has been a huge part of that. If you look at our history, we've been producing wine here in New York and here in the Finger Lakes for a really long time and at a really large quantity. We really stood out as one of the first American wine industries. Ever since then, it's always kept going.

I think one of the big shifts that we're seeing right now is the shift away from native varietals, which have always done really, really well here. Obviously, this part of the country grows grapes phenomenally all on its own. It's really been pulling back from that and shifting more and more recently towards more vinifera plantings that we see in this change in the industry.

Lots of cool stuff has happened here for a really long time with our natives - from the fortified wines that we used to see from Taylor Wine Company to the old Gold Seal sparkling wines. If you look back at the history with the influences that have come here, guys like Charles Fournier coming from Veuve Cliquot. He's an old cellar master there. We have a really cool diversity of styles that we made here with our own natural product, our own native varieties.

Photo: Christopher Bates (left) with Bob Bates

A lot of wine was made for grape juice, right? When did the shift come between the Finger Lakes as a region that was making grape juice and a region that was making quality wines?

Well, to a certain extent the Finger Lakes has always had some grape juice industry going on, but I think a large majority of that was still really more towards Lake Erie. Here in the Finger Lakes, we've had some of that; Welch's is obviously a big purchaser of our products here. There's always been a cottage wine industry going on. It got big. Back at the turn of the last century, all of Keuka was covered and Hammondsport was a major wine producing area. Places like, again, Great Western, and Taylor's and Gold Seal, all those were massive wine producers and largely focused more on wine than on juice production.

Talk about the terroir of the Finger Lakes. What kind of diversity do you have here?

The terroir here in the Finger Lakes is really interesting. I think one of the things that's super cool about it is the fact that it's very, very diverse. If you look at the way that this area formed in general, we all used to be under ocean here. That ocean used to run east to west. The different sedimentation levels, the different layers of soils, they all run east to west across New York. All our soil bands go this way across the state. When the glaciers receded and formed these Finger Lakes, it was really cool because they actually tore down this way. Along with that, you see all of these bands of soil that go around.

It's really cool to talk to a lot of the vineyard guys around here because the complexity of the soil is really stunning. Not only the complexity of the soil, but just also the diversity of the terrain. We're too continental here to really be able to regularly produce vinifera, which is a little bit more sensitive to cold. This area in general around here is quite cold.

One of the things that makes this place special is actually the lakes themselves. The fact that Seneca Lake right out here is 700 feet deep, it never freezes, and it's a constant 50 degrees pretty much year-round. This helps to create these areas, these pockets that actually stay a little bit warmer than all our surrounding areas.

As we look at the climate here in the Finger Lakes, as we look at the terroir, the diversity of grapes that it lets us really focus on, it's really cool. I think we're still sorting it out. When we look at our terroir within New York State here in the Finger Lakes, we're a little bit cold but we have these moderating factors that help with that. Within the lakes though, it's so diverse. Whether you're in Cayuga, or Keuka, or Seneca, or any of the other Finger Lakes, we have different depths. We have different weather patterns. As they come down from across Canada and across the Great Lakes and then hit the Finger Lakes, we get all these different climates happening in here.

Add to that the lake direction. All our lakes are basically north to south, so your vineyards are either planted east facing or west facing, depending on what lake is before or after it. There's so much cool microclimate going on here that it gives us the ability over time to make some really stunningly diverse and interesting styles of wine, I think. It's one of the things that I think is really fun here; our ability to grow a really wide range of stuff.

You grew up in the Finger Lakes.

Yeah, pretty much. I think officially I grew about four miles outside of the AVA itself. Yeah, I'm from up here. I spent my whole childhood in this area. I remember back when parents would have friends coming and relatives visiting. We'd always come over to the Finger Lakes Wine Trail and I distinctly remember loving to go to Bully Hill. I think Taylor was the other that I really liked. Back to the juice thing, they always had a little juice for kids. It's always a lot of fun coming here and visiting.

Things have obviously changed a lot. Back in the day, you wouldn't see Finger Lakes wines on three-star Michelin restaurants. Now, everybody in New York City that has an important restaurant pretty much has a Finger Lakes wine on it now. Talk about the change in the way that the wines have been respected in the restaurant community.

Well, I think it's one of the huge things that's happening right now; the change that we're seeing in the restaurants, the change that we're seeing in the perception of Finger Lakes wines around the country and, frankly, around the world.

The fact that New York City is highlighting our wines I don't think is anything shocking at this point with the eat local, drink local trends going on. We're a natural candidate for that. What I think is really stunning is that we're seeing Finger Lakes wines popping up in the best restaurants in San Francisco, and in the best restaurants in Texas, and in Paris, and in Japan. We're seeing the wines actually getting out there and really starting to command respect in their categories on a global stage, not just on a local stage, which is really, really exciting to me.

How have the wines changed over time? It seems to me that you're getting a lot of people now who have a technology backgrounds who have come from other winemaking regions that have added something to the culture here. How has that evolved?

I think the idea of what's happening in the Finger Lakes is really based on evolution. I think the evolution that we've seen happening is really important here. We've got this change that's been building over generations. There's no single turning point for it. If we look back, we see the days that we were just focused on native varieties and some of the wonderful stuff that can be done with natives, the push towards hybrids and then eventually the work that guys like Charles Fournier and Dr. Frank did for getting vinifera in the ground, getting vinifera respected, the work that Hermann Wiemer has done and all the guys that that have pushed for that, the work that the Glenoras, and the Franks, and everybody else around the lakes has really done. In more recent times, the stuff that guys like Ravines have done have really started to push that quality.

I think one of the things that we're starting to see now that I think is really big and really important is confidence. This has been one of the biggest changes that I believe I've seen personally. It's the change in people's minds and in the mindset of wineries, and winemakers that we can make wine that's okay to we can make wine that's pretty good to, wow, we can actually make wine that's great. It's cool to see.

Especially as the shift in wine styles around the world changes, as people get more and more into this idea that cool climate is a good thing. We shift more and more away from the big reviewers, the influence of Wine Spectator Robert Parker, that for a long time were pushing ripeness and the importance of these really big wines and concentrated wines. That's not really a style of wine that we're naturally able to make here.

Now, there's more and more attention towards finesse, and more detail, and more delicacy, more elegance, a little bit more acid. Those are the kind of wines that we excel at here. I think that we're seeing a shift because of what the consumer wants now; because of what the world wants and what is considered positive in wine these days. We're seeing more and more confidence here in the winemakers.

Not only that, it's been amazing to watch the new winemakers come, to watch people with other experiences, to watch people who have the opportunity to go and make wine elsewhere, who have the ability to go to France, or California, or Oregon and do all kinds of fun stuff, but choose to come here instead. It is really changing that game. We're starting to see more and more professionals moving to the area as opposed to, well, people such as myself who grew up here. We're getting more and more diversity from outside with more and more experience.

Add that to our building confidence that we can and should expect great wine from the Finger Lakes, not just okay wine, and the general consumer that's looking for these cooler climate styles, I think it's only natural that this whole area is going to really excel at that. The quality of the wine is getting better every singe year. It's been really fun just to every year be able to add more stuff where I'm like, "Yeah, that's actually really awesome. That's great wine. I'd love to show this to more people."

You're a Master Sommelier. How did you go about that process and why did you do it?

I went about the process of the Master Sommelier program mostly just for personal reasons. I grew up here. I've grown up cooking. I've been in restaurants my whole life pretty much. I just started working when I was young for beer money, and car money, and gas money, and started washing dishes, and cooking, and I absolutely loved it. I went to college around here and started transitioning from back of house to doing a little bit of both back and front of house and I got into wine and just started launching myself down that path. I loved it. I love learning about it. It gave me an outlet and something that I really enjoyed learning about, enjoyed studying.

I started in the Court of Master Sommeliers program with my intro exam while I was still going to school here and didn't really stay with the program for the entire time, but I was always doing stuff related to it. I was off making wine. I was off working in restaurants. As a somm, I was cooking. I was just doing tastings and tastings. When I got down to Texas a couple years ago and met Guy Stout, he got me back into the program. I spent the years of, I don't know, probably 2007 to 2013, really aggressively, and actively studying and preparing for those exams.

They're pretty hard. I think there are more professional baseball players than there are Master Sommeliers, right? How hard was the exam?

The exam was pretty challenging. To put in context, it took me 12 years from getting involved to passing it. The Masters itself took me four years. I took that exam four times before succeeding at it.

We have all kinds of fun stats about how it's the hardest thing in the world to do. Maybe some of that is accurate. Maybe some of that is not. I think there are a whole lot more people that try to be professional baseball players, at least historically. Maybe with all the attention our industry is getting now, maybe that will change in the future.

Then you became a winemaker. What was the thought process in becoming a winemaker? You also make beer as well. Is that right?

Yeah. I like to tinker. I like to make things. I love creating stuff. I started making wine in 2004. A big part of that was I just wanted to, I always find it fascinating. As a sommelier, as a cook, as a server, I tasted wine in a specific way with specific things in mind. Every time I would taste wine with winemakers, it blew my mind the way that they taste it, and what they were looking for, and how it was different. Even retailers and how everybody in different levels taste wine differently, look for different things.

I think that was a really big part for me was I was fascinated by the way winemakers tasted. I really just launched into it because I wanted to learn a little bit more about that. I want to understand why they were always looking for faults, and why they were so sensitive to it, and the eye in which they looked at it. I just went off to Italy and Germany and just started working in wineries for a while. I got back here and kept doing it. I worked with some friends out in Walla Walla and out in the Willamette before launching on what we did here.

What is the philosophy behind Element Wines?

My philosophy behind the winery is to help push this, keep this evolution. Really for me, a big part of the philosophy behind Element is to really keep this evolution happening here in the Finger Lakes. It's to keep pushing and to keep trying to build that confidence. We are a small winery so it's a little bit easier for us to focus on really pushing that level and to really try and elevate what the expectations are here in the Finger Lakes.

We started the winery as a concept back in 2006, and we've been pushing it ever since. With our first release from 2009 and 2010, we've really tried to keep pushing quality. We've really tried to keep moving the potential here for what can be done in the Finger Lakes. It's been really cool to see everyone else keeping pace of that. The idea for us about the winery was really just to help develop, to help push and to help keep evolving the Finger Lakes.

A lot of winemakers are focused on specific plots or making very terroir specific wines in terms of this lot or that lot. You take a different approach where you're blending from different parts of the region.

I still think that we're in our infancy here in the region. I still think that we're at a point where we still don't actually know what the Finger Lakes taste like. We still haven't really sorted out what our style is here, and what our fruit tastes like here, and what differentiates that from the rest of the world. A big part of our philosophy as a winery is to really focus on that. It's the focus on creating a Finger Lakes style. To that end, a big part for us is to try and source as much fruit from as much diversity as we can. I don't really want to make single vineyard wines yet because I don't think that we know what the base is to differentiate that from.

Our goal is to try and get a much fruit as I can from different lakes, from different soil types, different rootstocks, different growers, different growing methods and really ultimately bring that together in one wine that truly represents the Finger Lakes is the goal. I think the single concept that's perpetuating right now in the wine world is a little weird. The idea that singularity is better, single clone, single vineyard, single this, single that. I don't necessary think one is better or worse. They're just different expressions of it. This idea to make a higher end wine or to make a reserve wine needs to come from a single vineyard I think is short-sighted.

Burgundy is a really good example of that where if you don't know what the Bourgogne Blanc or Bourgogne Rouge taste like, then the Premier and the Grand Crus don't make any sense. You need to have that base knowledge to understand why these special areas are better, why these special areas are different, and why these special areas cost more.

For me, my big part is just trying to get to a point where we understand what Syrah tastes like in the Finger Lakes and what Pinot Noir tastes like in the whole of the Finger Lakes. As we do start to define these special places for it, we know why. We can say, "This vineyard is a little bit riper. This vineyard is a little leaner. This vineyard is spicier." Just trying to get to a point where all of that make sense.

You're making Syrah which is somewhat unusual in the Finger Lakes. Tell us about the Syrah.

Syrah here in the Finger Lakes is something that I think is quite controversial. It's something that I'm absolutely in love with. It happened about five, six years ago, maybe seven. I remember attending a tasting in the city where we were doing a Syrah blind tasting and going through the wines. Everything was pretty obvious except one wine. We were all confused as to what this was. It turned out it was super cool climate California Syrah. Everybody was not in California. It was Wind Gap. These guys are dong really interesting stuff really close to the ocean in climates that are really cold.

It was one of those things that I started to think, "Wow, if this is what they're going for, and this is the ripeness level that they're getting, and this is the wine that they're able to make with that fruit, I don't see why we can't do this here in the Finger Lakes." I went on this scavenger hunt looking for Syrah. Luckily, I was able to find a vineyard right across the way from the winery here that has it planted. I've been working with that fruit and trying to get more fruit ever since.

I think Syrah is funny. It's a grape that we all think of as warm climate. We're more familiar with Syrah, Shiraz or California big Syrah styles. Even the Northern Rhône, we always think of as warm climate and it's not. The Northern Rhône, especially in the Côte-Rôtie area, has that cooling effect that we get from the Mistral that we see happening. It is quite a bit colder than what we generally think of probably because of our impression of the Southern Rhône and the heat that is down there. Syrah does really well there. Syrah does really well in a lot of these cold climate pockets.

In Australia, if we look, there are some really cool climate areas that do stunning Syrah, some stuff that we see coming out of California. I thought it was something that we could do really, really well here. It's a fun grape.

It confuses people here. Again, a lot of times people immediately hear Syrah and think, "It's warm climate." It's not. The Finger Lakes is funny. Everybody thinks of us as a cold climate or a cool climate and we're really not. We actually have a moderate summer. It's warm here in the summer. Ripeness usually isn't the biggest issue. Our biggest issue is the fact that we're a moderate summer but have freaking freezing winter. It's that winter kill that's a real challenge for stuff like Syrah. This grape variety tends to be a little bit more cold sensitive.

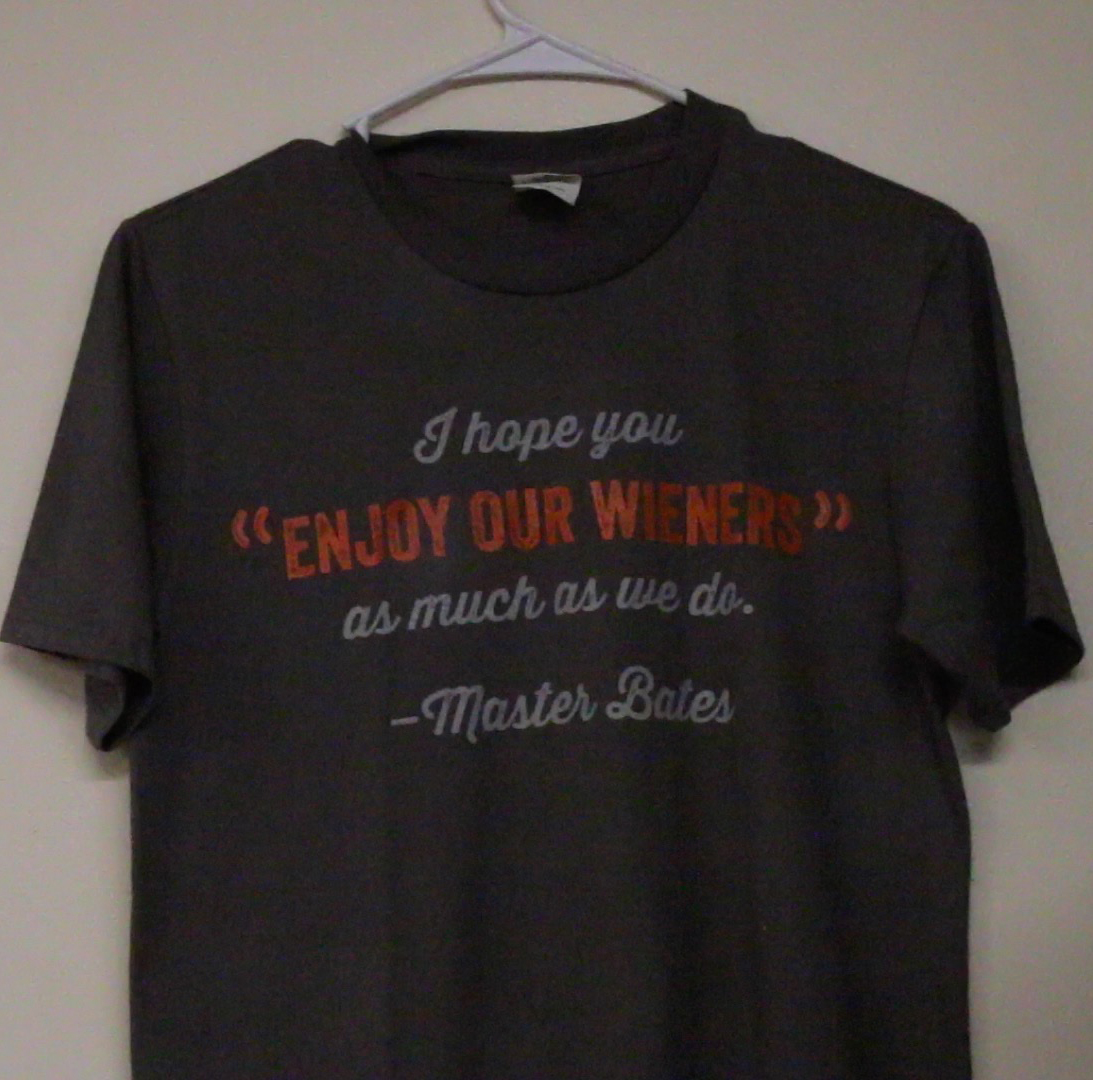

Christopher, tell us a little bit about the Wienery.

The Wienery is really a restaurant concept that my wife and I came up with and opened about two years ago up here. Really the target of the whole place is to act as a local hang-out spot. It's super casual, super simple, but with a lot of love and a lot of care. Hot dogs, hamburgers, french fries but with a lot of energy and a lot of passion. Super simple stuff, fun little wine list, fun little beer program. Ultimately really designed to be a local's place. A place for all the wineries to hang out. A place for people to come and taste maybe wines that aren't necessarily available here in the Finger Lakes all the time or beers that aren't always around.

How do your cooking and wine passions intertwine?

It's really funny to me. In both cases I think there's a similar philosophy. I don't want to put stuff in anything that I don't need to. I don't want to put stuff in food. I don't want to put stuff in wine that I don't really want to put in my body. I think in a lot of ways, they're a similar vein in that our focus is on trying to do things right, trying to do things well, trying to do things by hand and from scratch. I think the two are really different.

I think that's, for me, what's really fun is in the kitchen, we really hyper-focus on control, looking to really make things exacting and specific. I get out all of my recipe and tinkering. What if we did just a little bit more of this and a little bit less of this? What if we ground it just a little differently or we cut it differently? It's fun because I get out all my control and my obsession for making things just right in the kitchen. When I'm in the winery, I get to be a little bit more relaxed.

For me, ultimately, my goal still is really just to create a wine that taste like the Finger Lakes, not the way that I want it to taste, really, but just the way that the area tastes. Because I think I get that control in the kitchen and eventually I'll have that control in brewing. It's a little bit easier for me to just let the wine do what the wine wants to do and not be so controlling and not be so demanding, like, okay it has to be exactly like this. What if I did another day of this or another day of this? It's just sort of, okay, it taste good now. Let's go. Next step. Next step. Cool.

You work with a lot of different growers. What's that relationship like? How much influence do you have on the process?

Ultimately, I work with roughly about 10 growers of vintage. I would love to see that expand. It's a bit of a challenge of logistics. I work with about 10 growers on average throughout the year. It depends on the grower themselves, that's what really determines my relationship with them. Some growers that I work with, I have had experiences where there are certain things that maybe I don't like, and so I'll work a little bit closer with them to say, "Hey, I really want the fruit cropped this way, or I really want it shaded this way." Then others, I've been getting their fruit for years and they're doing a stunning job at it. Frankly, they do that for a living. They're way better at it than I am. If their fruit is giving me what I really want, I like to just let them do that.

Ultimately, right now, I'm still working a lot around Seneca. I'd love to get more diversity. I'm still trying to figure out how to get a little program together, and I'm obsessed with the idea, where I want to try and get somebody this harvest or next harvest to actually go around and buy, I don't know, 50 pounds of fruits from every grower of Cabernet Franc and every grower of Pinot in the Finger Lakes and bring that back, and we can make one wine out of it to ultimately try to do ... This is all of the expressions of Cabernet Franc from here. It's a bit of a logistical challenge. October is a busy month, so I don't know if I'd get around to it but that's my plan.

Who are your influences as a winemaker?

As a winemaker, I think I'm pretty heavily influenced, not necessarily by a specific person so much as by styles of wine, by places that I taste wine from.

I think that there are some winemakers who I respect a ton. There are a lot of winemakers who I respect a ton. Some of whom when I hear things that they're doing, I'm like, "That'd be kind of cool to try."

Ultimately for us, we're not doing that much winemaking. Our process is super simple. It's all spontaneous ferments. There are no additions. Fruit comes in out of the vineyard. We spend a ton of time sorting it, which is certainly a manipulation all on its own but something that we do really heavily. Then maybe it gets destemmed or doesn't, ferments on its own until it's done, and then gets to press off, and chills in old oak. I'm not really trying to be all that creative necessarily in our winemaking. I try to be pretty hands-off with it.

I think probably more of an influence for me are the wines that I love from the rest of the world such as the Syrahs from the Northern Rhône that I absolutely go crazy for, or Cabernet Franc from Loire. Not that I'm trying to make those wines. I don't want to make Northern Rhône's wine. I don't want to make Chinon. I love them. I want to make wine with that sensibility, with the flavor of fruit and earth above the flavor of oak with the idea that wines don't need to be big and extracted to be delicious, and elegant, and layered, and balanced.

I use those as examples not certainly in any way to try and copy. Ultimately, again, our goal is to make wine that tastes like Finger Lakes, not like wine that I like from somewhere else. We're still trying to find that, what that tastes like. Who are we? I think there's a lot of development that has to go in that. I think that's one of the cool things to look at; what other winemakers who have that similar philosophy are doing. It's really cool.

I love a lot of the guys in California, and Oregon, or Washington who are trying to make wines that are reminiscent of the Old World. I also love it when I see people just say, "Hey, yeah. I love Burgundy and I love Chinon, but it's warm here. We're not going to try and make these cold climate fruit wines. We're warm and we're going to balance it. We're going to make this into a wine that represents their place." For me, that's a really big part of my influence. It's to just try to take what I like from the styles of other people's wines and what I like about the personality of them and trying to bring that to fruition here with the fruit that we have.

Christopher, you're a red wine specialist. You stopped making Riesling, why?

For me, focusing on red wines as a winery is really a personal choice. It's something I want to do, not to say anything about what other people do or whether I love Riesling or not. It's really just, for us, with our concept of really trying to work to push the expectations of what the Finger Lakes can do for the idea of really trying to push people's mindset of what's possible here. I think there's so much great Riesling already happening here. There are so many producers that are just doing a stunning job. We talked about Ravines earlier and Wiemer earlier. Those guys are killing it, but also a lot of new guys like Bellwether, and some of the stuff that Steve Shaw is doing. All these guys are just doing really cool things with Riesling. I'd love to be a part of that, but I feel like I can have a much bigger influence on the future perception of what's possible here by working on other things.

Personally I love the style of red wine that's here. I think that historically people still don't necessarily associate it with the Finger Lakes. I still think that there is maybe a stigma in people's minds that the Finger Lakes can't produce great red wine. I think that's completely wrong. That's really been a big part of my focus; really trying to prove that we can stand proud and stand strong. That our wines don't need to be good for New York wine or good for the Finger Lakes. Our red wine is good wine. It's good wine that could stand with wine from anywhere else. It's a big part for me.

In terms of vintage variation, how much do the wines change from year to year?

Pretty drastically. We're in such a marginal climate that a big part of really what we're doing is ... We're one of those areas where we have to push to the extremes to get the best. When we look back at other great areas that ... I think as wine lovers we really, really appreciate places like Burgundy, places like the Mosel, places like Champagne, to be honest. These are in places where you really have to push to the extremes. If your weather is pushing back, you're going to be able to taste it for better or worse. You're going to be able to notice it. The vintage variation here is still really strong. I think it always will be. I don't think that ...

As growing gets better, as we get better at controlling our fruit, as we get better at controlling disease, pressure and all of these things, I think we'll certainly be able to push that to a little bit more consistency. I think we're not in a place where we can pick in September or, if it's a cold year, wait and pick in October. We already pick in October and in November in a lot of cases. We can't push it further than that. If it's cooler vintage, we're just going to have to pick slightly cooler styles.

We have a huge variation with that but I think that's part of the charm of the area. Trying to find that balance where sometimes we do have big vintages. 2012 was super ripe, super concentrated. '13 was a lot lighter. Both exciting, both interesting, just different.

Are you happy with the Syrah? Do you think there's more to come with it?

Well, there's a ton. I think that, at this point, anybody that's thinking that we're making the best wines that we can make yet, doesn't have big enough goals or dreams yet for the Finger Lakes. I've been super excited about even just tasting what I've done so far and tasting the last five vintages in a row. I'm so excited with the potential of it.

Over those years both from my own standpoint of knowing how to make it, but also just the vineyard work that we've done in that one is really showing the level of concentration we are hitting versus what we were getting back then. The depth and complexity of the fruit is amazing.

I'm a huge proponent for Syrah and for Pinot here in the Finger Lakes. Neither are the easiest grapes here. Cab Franc is clearly the most natural here. Cab Franc and Riesling are the grapes that prove themselves to be the most naturally acclimated to the region or at least the region as a whole. There's so much microclimate that Syrah can fit into here, and Pinot as well, and Chardonnay.

As we divide up and learn more about the microclimates and we find where things like Syrah, and Pinot, and Chardonnay are going to work. They don't work everywhere. Cab Franc and Riesling do really well across the huge range here. You plant both sides of the lake, closer and further from the lake. Stuff that's a little bit more sensitive like Syrah, we're going to find it's going to need to be close to the lake. Over in The Banana Hammock, they're doing really good with it over there.

I guess part of the problem is that there's probably not a lot of people making it, right?

There's now eight of us now. Actually Hector does a really good job with it. Hector Wine Company. Justin makes a really good one there. Atwater does it. There aren't a whole lot of plantings of Syrah. I think it's funny. It's not something that's going to grow everywhere. You're just going to find the little pockets. Hell, I got a little bit of Grenache.

Really? Wow.

Yeah, here. The Finger Lakes Grenache. I'm not saying planting Grenache is a good idea. It's not. It's survived through the last two winters, three winters and cropped. If Grenache is going to survive, then Syrah certainly will. It is just in little pockets, little protective areas, little spots by the lake but other stuff is really hard as well. There's a lot of concern, a lot of criticism towards Syrah, but Gewürz is a real challenge here. Gewürz freezes every year.

I saw someone is even making Blaufränkisch.

Yeah, yeah. Actually I make some as well. Lemberger is awesome here. I think it might probably be the second best red grape for acclimation to the climate after Franc. Red Tail Ridge, Nancy is a leader in it. You'll see more Lemberger and Blaufränkisch now. There's a lot of it happening all around and there's some really cool stuff. The variety itself, it's tough enough to handle our winter. It's tough enough to fight disease and be resistant. Organic beautiful flavor in it. It's a really cool grape.