Clos Saron is a small winery located in the remote town of Oregon House in the Sierra Foothills AVA. Founded in 1999 by Gideon Beinstock and his wife, Saron Rice, the winery’s tiny production of naturally-produced wines are made with a less-is-more approach. Grapes are farmed without pesticides, fertilizers or herbicides, and there is minimal intervention in the cellar. The wines, with whimsical names like Kind of Blue and Tickled Pink, are sought after for their distinctly pure expression of the Sierra Nevada Mountain terroir. In January of 2012, with the interest in natural wines beginning to soar, Matt Kramer in the Wine Spectator wrote that Clos Saron was one of the small wineries “quietly reshaping America’s vision of fine wine.” [Wine Spectator].

Beinstock’s journey to Clos Saron has been full of compelling twists and turns since leaving his native Israel forty years ago. While pursuing an artist’s life in Paris, he experienced a period of severe existential angst that led to his joining the Fellowship of Friends, a spiritual cult based in California. The group believed that, through the study of fine arts, true consciousness (in today’s terms, the state of being “present”) could be reached. Creative endeavors, like music, painting and literature, were explored as a means of reaching an idyllic state. And since the Fellowship’s sprawling property in the remote Sierra Nevada mountains — all rambling hills and steep granite terraces — lent itself to viticulture, winemaking was seen as another means to attain enlightenment. The group’s members planted 365 acres of vineyards within just a few year’s time in the late ‘70s, and so began Renaissance Winery.

Beinstock, a wine lover since his days in Paris, was eventually named head winemaker, a position he held for nearly 17 years. While the wines produced under his care didn't gain much critical acclaim, they were (and still are) revered by those in the know. Beinstock eventually became disillusioned with the Fellowship and, in 2010, after three decades with the organization, left to focus on a new way of life. For the past ten years he has been tending his own property, along with a few other vineyards, to make Clos Saron wines.

We caught up with Beinstock to learn more about his fascinating life story, and why he believes that a wine’s most revealing attribute is its expression of origin.

We caught up with Beinstock to learn more about his fascinating life story, and why he believes that a wine’s most revealing attribute is its expression of origin.

Can you tell me a little bit about your background?

I grew up in Israel and I stayed there and I served in the army for three and a half years. Afterwards I went to an art college. I was painting at the time and studied art and my life was getting complicated. As a student in college, I was starting to be, I mean to say a success is a big word, and I feel is an overstatement, but I started attracting some attention from some people in the art world and attention from girls and I just was drowning in it.

And, I was more and more unhappy with myself and one of my endless girlfriends at the time was at the exact same point in her very brief artistic career and life experience. We decided to jump ship and do the two most extreme things that people in Israel can conceive of, which is get married, which nobody in our immediate milieu was doing and leave the country, which was, in my generation, almost like a betrayal. So we did that — got married, and left the country and started roaming around Europe. And, we stayed in Greece for a little while, and then hitchhiked through Italy, ended up in Switzerland for a while, continued to France. And in France, I really felt at home, partly because of my background. I grew up speaking Hebrew and French, that's why my accent is sort of a mish-mash. My mother was reading bedtime stories to my sister and I when we were kids in French. she only spoke French to us when we were babies, young kids. Her mother was French, her father was Flemish and she grew up in Belgium. She was Belgian, but part of the Belgian population that was only French speaking. She understood Flemish but was certainly not using it as much. So I grew up with French literature. That was what my world was about. So once I got into France, I felt at home and we sort of got stuck in Paris because we loved it.

How did you end up coming to the United States, to California? Can you take us through those series of events?

My main interests at the time were art and drugs. And wine started replacing drugs because I had no budget to buy them. Well, in Israel, I was a hippie in the '60s; my version of the flower children of California, and so we were doing a lot of hashish smoking and I couldn't afford it in Europe, so I felt wine was a decent alternative to that. And my preconceived idea of wine was that it's a beverage, it contains alcohol and it's good to drink. And so that's where we started but, very quickly, I realized that wine had more to it than that and so I started becoming interested in it.

Prior to this, I also had another interest, which is in philosophy and I don't know exactly what word to use for this, but mystical traditions such as Sufism. And I was very interested in the writings of a person called George Gurdjieff, and that led me to finally join a group because it's a practice, it’s not a philosophy, and so you need a group that can teach you how to use it. So I was looking for such an environment. When I was in France, I joined this group called the Fellowship of Friends that was based in California and was practicing, supposedly, these ideas.

And they — surprise surprise — were developing right at that time a vineyard in the Sierra Foothills of California in a place called Oregon House. I thought, “That’s nice” and I decided to go visit. So in 1979, I went to California then went back to Europe, came back, went back, came back and finally stayed in California from December 1991 until now. So you joined the fellowship when you were in France?

So you joined the fellowship when you were in France?

Yes and eventually, much later, I became the winemaker there, about 15 years later. And it wasn't really by ambition or by, "Oh, I want to be a winemaker," kind of thing, it just happened because I was seeking wine education. I was infatuated with wine. Especially while living in France, I befriended more and more people in the industry that were extremely instrumental in teaching me, especially, the passion for the expression of terroir in wine, the soil. And for me, the realization that the most memorable wines are those that somehow have the ability to capture the essence of the place, especially the soil, but also micro-cimate and the practice of farming, whatever it is, those wines that capture it make my heart sing.

And gradually I developed more and more the passion for it, and that eventually led to my getting involved in different capacities in the periphery of the wine industry trade. But I had no hands-on winemaking until I moved back to California after my last time living in France and in the UK selling wine. I moved back to California and they asked me if I wanted to keep selling wine for them — that was Renaissance winery, when they released their first wine, and that was not of interest to me so I thought, "Well, the only thing I haven't done so far in order to round out my wine education was hands on working in the wine cellar, after which I'll go back either to art or programming, which I’d done in between." And I never left. I basically found my calling.

And the vineyards of the Renaissance Winery are quite unique. Can you talk about that?

There probably are such vineyards somewhere in the world, but basically if there are any, you'd be able to count them on one hand. It gradually was developed with no business plan, with no real notion of what is grown, what the scale of the vineyard is going to be here, what are we going to grow exactly, what wines are we going to make, where are we going to sell it or anything like this. It just grew as an extension of this spiritual cult activity to suit their spiritual pursuits in whatever capacity, and it gradually developed itself.

So the first year in 1976, they planted 10 acres of vines, Cabernet Sauvignon, a year later they planted roughly 20 or 30 acres of Petite Syrah, Zinfandel, more Cabernet Sauvignon, some Riesling, and next year another 20 or 30 acres and on and on. But the year that I got there, in 1979, I was part of a crew of 35 young people that planted the 110 acres in one year. And it was completely manual labor, it's post hole digging into very rocky soils and such very hard labor and very intense. And that was my first experience there. And what gradually developed was the 365 acre vineyard that was just magnificent. It was all on contour terracing and hills had from the bottom of the vineyard to the top of the vineyard 700 feet of altitude difference, which is very significant for one continuous vineyard. It's extremely unusual. All the different exposures, because it was all on the contours of these hills, three hills that were all covered. So there was south exposure, north exposure, west and east. A myriad of soil types and different drainage, different wind conditions. So it was an incredibly complex layout, topography and a microclimate array that initially were planted basically with three grape varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling, and Sauvignon Blanc, and by utterly ignoring the terroir, completely. What I mean by this is that when you go on a contour terrace that goes around hills, you change the exposure at every point. And when you harvest these grapes, you go on the terrace and you harvest all these fruit and, unavoidably, you get unevenness, you get some fruit that is underriped, overriped, mildewed and so that goes into the same beans and it's made into wine which is not a good thing to do, but that's how it was done.

All the different exposures, because it was all on the contours of these hills, three hills that were all covered. So there was south exposure, north exposure, west and east. A myriad of soil types and different drainage, different wind conditions. So it was an incredibly complex layout, topography and a microclimate array that initially were planted basically with three grape varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling, and Sauvignon Blanc, and by utterly ignoring the terroir, completely. What I mean by this is that when you go on a contour terrace that goes around hills, you change the exposure at every point. And when you harvest these grapes, you go on the terrace and you harvest all these fruit and, unavoidably, you get unevenness, you get some fruit that is underriped, overriped, mildewed and so that goes into the same beans and it's made into wine which is not a good thing to do, but that's how it was done.

I did not know it at the time, but when, years later, going back to the point where I said, "Yes, I'll work in the winery for a little bit," roughly a year later, by necessity, the winery fell in my lap like a hot potato. The winemaker at the time, a woman called Diana Verner got remarried and pregnant, and was ejected out of the winery, both by her preference and also by some kind of political maneuvering that was happening within the Fellowship organization. I was really not part of, but still it was perceived as if I somehow took over. But before I even became officially their winemaker, I started practically managing the winery and making their wines. And that was from the 1993 harvest.

And in terms of what happened later, I had one very memorable conversation with Diana when I was her trainee assistant winemaker, which was my title. And I asked her, remember where I came from wine-wise was from a very strong tradition that wines are meant to express the soil. So I asked her, simply to understand, it was not a challenge, it was a question, "Where in our vineyards did we get to the best grapes from because we have Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc?” Because they were making like old self-respecting California wines, they had estate level wines and reserve level, so the reserve must come from the best locations, I would assume. "But what does it mean? Where are they in this vineyard?" It was very complicated.

And she gave me an answer that indicated that she did not know or care. She did not feel it was important, which to me was equal to that she does not understand what she's doing. But a year later when I, so to speak, inherited the responsibility of the winery, that was my first urgent task, to sort out what was going on there because we had no clue. So I started breaking down those fermentations to smaller and smaller and smaller individual lots, small fermentations. So we were getting fruits from places that we didn't know what they were producing and I had to figure out urgently what was going on in the vineyard. Especially for the first two years, but even later, we ended up having like 75 to 85 fermentations of Cabernet Sauvignon, in various capacities, and something like 35 fermentations of Sauvignon Blanc. So it was very, very complicated, but very quickly what was emerging was that obviously there are quality variations, obviously there are typicity variations that were very crucial. If I wanted to make something of note or of true character, we had to zero in on them.

So we were getting fruits from places that we didn't know what they were producing and I had to figure out urgently what was going on in the vineyard. Especially for the first two years, but even later, we ended up having like 75 to 85 fermentations of Cabernet Sauvignon, in various capacities, and something like 35 fermentations of Sauvignon Blanc. So it was very, very complicated, but very quickly what was emerging was that obviously there are quality variations, obviously there are typicity variations that were very crucial. If I wanted to make something of note or of true character, we had to zero in on them.

And we also started this phase in the vineyard development of what you call migrating varieties because since the varieties were planted on this contour terracing, we had to start breaking it into exposure, into microclimate blocks, and the lousy ones had to be basically converted to something that could succeed there. So if we had an area of Cabernet Sauvignon, that was not ripening properly because it was too cool, we could try to graft it over with Pinot Noir, or if it was too rocky for the Cabernet to excel, we could try grafting it over with Syrah and on and on and on. So we started this extensive regrafting program and we started getting more and more information. How long were you the winemaker for Renaissance?

How long were you the winemaker for Renaissance?

Officially from 1994 to 2010. So 16 years, practically 17.

Then in 2010 you decided to leave this fellowship?

I decided to leave long a long time before that.

What led you to your deciding that you didn't want to be a part of the fellowship anymore?

After a few years of truly practicing what they were advocating and realizing that yes, it does work, I also realized that it was not what it was claiming to be in terms of the tradition where it was supposedly coming from. And it was really not my spiritual home anymore. I did not want to hurt them, I respected what I got from them, and I did not want to hurt my own interests because back then Clos Saron, was born, and so I did not want to hurt our own interests. So I took almost 10 years to gradually separate every thread of the two things that were intertwined.

When you started Clos Saron, were you purchasing all of your fruit?

No. The seed for Clos Saron was planted in 1995 by a friend of ours, Leonard, that used to work with me in the vineyards at Renaissance. He took some cuttings of Cabernet Sauvignon from the Renaissance Vineyard when we were planting them and he planted them in his own home site on his parcel. The specific location where he planted was a microclimate that was too cool and unsuitable for Cabernet Sauvignon.

Renaissance is a large vineyard, and it was less than half a mile from the beginning of the Renaissance vineyard. So he was fighting with the elements for about 15 years or so, and then he was giving up. I was making wine at Renaissance, and my wife, Saron, we just got married, and she was working in the vineyards at Renaissance. He asked us if we wanted to take over his little vineyard, it was half an acre of vines, and play with it, just to have fun with it. And what we got his permission to do was to graft these two Pinots, because Pinot could succeed in a place where Cabernet would not, and in 1995, we grafted those Cabernet vines to Pinot and doubled the density. So between every two existing Cabernet vines that were grafted, we planted Pinot because Pinot likes to be more densely planted than the way it was at the time. Then a couple of years later for us, it was clear that at least the microclimate is perfectly suited to Pinot, and he decided to sell the land and we jumped on it. And that's where Clos Saron came to be. So that was the origin of it. And initially, we were wishfully thinking that maybe we would only produce this Pinot Noir and I very quickly, I realized, "No, this is not practical. It's not enough fruit, it will take us many years to come into larger production. So though it was not a signed contract, we still had the lease on specific acreage in the Renaissance vineyard. A little of bit of Syrah, a little bit of Cabernet, Petit Verdot, Sauvignon Blanc, Viognier, Roussanne, a bunch of different things.

Then a couple of years later for us, it was clear that at least the microclimate is perfectly suited to Pinot, and he decided to sell the land and we jumped on it. And that's where Clos Saron came to be. So that was the origin of it. And initially, we were wishfully thinking that maybe we would only produce this Pinot Noir and I very quickly, I realized, "No, this is not practical. It's not enough fruit, it will take us many years to come into larger production. So though it was not a signed contract, we still had the lease on specific acreage in the Renaissance vineyard. A little of bit of Syrah, a little bit of Cabernet, Petit Verdot, Sauvignon Blanc, Viognier, Roussanne, a bunch of different things.

And we started making a white wine, that we called Carte Blanche, a rosé that was called Tickled Pink, and three red wines that were all Syrah-based: one pure Syrah, that was called Heart of Stone, one Syrah Cabernet co-fermentation that we called Black Pearl and one Syrah Merlot called La Cuvée Mysterieuse these were Renaissance based wines.

You continued to work as the winemaker for Renaissance after starting Clos Saron?

I was doing both. It's very common in the California wine industry for the winemaker to have their own project. And there is really, rather than any harm, it actually benefits both wineries. It’s not like in Europe, like in Côtes du Rhône, where you have thousands of people right next to each other, all competing for the same appellation, pretty much the same wines. In California, there's space, you know, and so instead of being one winery, there are five, it’s a benefit, because there's more attention, there's more variation, people have more interest and hear about it.

So then what happened when you left the fellowship as far as your lease with the Renaissance winery?

Basically they severed their relationship with ex-members. So I knew before it happened that I was going to lose access to Renaissance's fruit. So from 2010, I started looking for alternative sources and that started a phase of purchasing fruits in addition to producing our own grapes.

What happened with those vineyards at Renaissance? Are they still active?

Renaissance stopped producing wine sometime in the last five years. It seems to stop, then start for one year, stop again. Anyway, they stopped. When I was still a wine maker in the 2000s, there was a five year period that there was hopes of managing the company and I initiated the move to take out a significant proportion of their vineyards in order to give them a chance to survive economically because they didn't have the infrastructure, the interest, or the knowhow to produce wine from 365 acres. It was really not practical. So yes, as long as it served their spiritual purposes, yeah, great, good.

But once their focus moved elsewhere, they couldn't handle it. It was going to bury them. We started removing vines and by the time I left, about 90% of the vineyard was gone. So from 365 acres, there was something in the neighborhood of 50 acres that remained, roughly, maybe 35 of them were estate farmed, and some were just left abandoned. And now there were other people that farm, there are two entities that farm on the Renaissance vineyard. One is called French Town Farms, two people that are good friends of ours and that were our interns, and that's where they learned winemaking. They went on to create their own label and they signed a contract with Renaissance, and they're farming about 20 acres there. Then there's another entity called Grant and Marie, And Grant is the person that used to be the vineyard manager at Renaissance many years ago, and he still farms sections of that vineyard and makes his own wine from that. Let's talk about your winery, Clos Saron. Can you tell us about it?

Let's talk about your winery, Clos Saron. Can you tell us about it?

Clos Saron is named after my wife, Saron. So the person is Saron, and the wine is Saron. Our romance started in the vineyard. At the time, as I said earlier, she was the assistant vineyard manager at Renaissance for many years and I was making wine there, and we had many projects that brought us together in the vineyards. So we were inspired to do the same thing. We shared the same passion for the specific expression of the terroir in the wine. So when a new opportunity to start our own winery happened, we grabbed it and we started this production. It was always based on this half-acre vineyard.

Clos Saron from the get go was based on our farming of Pinot Noir, and it started as a half acre vineyard, but when we purchased the land in 1999, we expanded it to about two and a half acres of Pinot, and then, as I said earlier, we got into farming some fruit at Renaissance, and producing other wines. Later on, in another phase when we lost access to the Renaissance vineyard, we started buying fruit elsewhere, like in Lodi or closer to home. Lodi is located roughly two hours drive south from where we are. So ever since then, which was 2010 and on, we've been looking for vineyards that are closer and closer to home that can provide us with high quality fruit and that would also be close to our approach, which is chemical free and where there's really more of a thoughtful, intelligent use of the vineyard rather than commercial farming, which is meant to produce higher volume, higher quantity rather than quality.

Are you certified organic?

I'm not certified anything. We were both cult members for long enough so we do not want to join anymore cults, be it organic, biodynamic, natural or anything. We are focused on what makes our hearts sing. And this is the expression of soil in wines, it’s very simple. And I know I'm repeating myself, but for me it's an endless road that we're following because it sounds simple, but especially now with all the ecological Armageddon that is happening around us, it's becoming more and more difficult to farm vineyards successfully in California without the use of herbicides, pesticides, and all kinds of enhancements that allow you to sustain it a little bit longer as the ecology, our ecosystem, is falling apart around us. But that's where our hearts are and that's what we're trying to do.

How does your experience at Renaissance inform what you're doing today?

In many ways. I mean, the reason why I was talking in so much detail about that early phase of looking for the correlation or the symbiosis between specific grape varieties, and specific terroir is that yes, it is my passion, but also if you think about great vineyards, wherever they are, if it's California, Montebello or wherever, your favorite vineyards anywhere, Lafite in Bordeaux or Richebeaux in Burgundy, it doesn't matter. All of these, if you think about it properly, you realize that it's both the grape and the soil and the microclimate that has to be ideally suited to each other because without any of them, it shall not be. Meaning if you take Richebeaux and replant it as cabernet sauvignon, you'll get mediocre wine. If you take Lafite and plant pinot there, you will get the mediocre wine. If you should take Montebello and plant it with, I don't know what, you will get a mediocre wine. I'm not familiar with the Montebello microclimate, therefore I'm not an expert there. So this has been my life pursuit and it started with these two intense years of, "Oh, what's going on here?” in the Renaissance vineyards.

And so Clos Saron, by then I knew by experimentations that that microclimate was perfect for Pinot, and as it happened, the soil variation, soil type there, which is also unusual for the foothills, an isolated pocket of volcanic ash and quartz, which gives the wines very strong character. And this combination creates something that is very special. It's a jewel.

We proceeded to plant other vineyards locally and I was using the same experience. By now I can go around our area — I'm not all-knowing, I don't know much in other regions — but in our area I can go to my friend's house and tell them, "You know, you could plant whatever right here and you will have very good success," because I pretty much got it. It's not foolproof, but I got the basics. And we keep developing it.

We found an ideal vineyard and microclimate for Syrah, and we planted two acres of Syrah there. We called it Stone Soup and it's less than one mile away from where the home vineyard is where we produce the Pinot. But it's as if you were in an entirely different part of the world. The trees are different, the microclimate is a lot warmer. It's south facing with very steep rocky slopes. The home vineyard is gentle and rolling low rocks, and again, volcanic ash. Stone soup is a decomposed granite, maybe not even decomposed, maybe just granite rocks with hardly any topsoil, so it's dramatically different and a lot hotter. Can you tell us a little bit about your specific vineyards?

Can you tell us a little bit about your specific vineyards?

At this point we are farming eight acres in total. It's a very small scale, but if it was to produce what is considered normal commercial scale production for a vineyard, which would be somewhere between two and say three and a half, eight tons per acre, we would produce all the wine that we need because our total production is up to a thousand cases a year. In fact what's happening is that all of our vineyards are producing less and less because of all kinds of ecological factors.

But the eight acres are comprised of two acres of Syrah, co-planted with some Viognier and that's what we call the Stone Soup Vineyard. It's planted on decomposed granite. It's extremely rocky, so there's very little decomposition there. It's almost bare rock with very little topsoil. It's at 1900 feet altitude, south facing, a very steep slope. It's really an idea like a textbook terroir for Syrah and something that is very counterintuitive about it is the expression of the wine. When you taste this wine, a lot of people would say, "This must come from a cooler microclimate or from a cold climate," because it's very lively, high in acidity, relatively low in alcohol, and this is all quote unquote natural, meaning we don't add or adjust any of these factors. It is the way that it's picked. But what happens there is that the intensity of the heat and the stressful nature of this terroir, the stress that it implies for the vines there, basically they stunt the vines at a certain phase in the season. During the season, at some point the vines just get stunted and they stop accumulating sugar in the grapes and they stop dropping the acidity. So, even though it's a very hot microclimate, it produces wines that tend to be lighter in alcohol and more intense in acidity. So very different profile.

The home vineyard is at 1600 feet, so slightly lower. It's roughly one mile as a crow flies down from this Stone Soup vineyard, and there we find Pinot Noir. It's a much cooler microclimate, roughly five to 10 degrees cooler than Stone Soup vineyard — summer and winter — and a lot more sheltered, and there we're sitting on volcanic ash and quartz, so a very different soil type, which is pretty rare for the Sierra Foothills, I mean the volcanic ashes. And there the Pinot Noir is planted very densely, and we get a very interesting expression because people don't expect the Sierra Foothills to produce any Pinot, and if there would be a Pinot, you would expect it to be very rugged and to taste like something that comes from a hot region, and it does not. Again, it is ripe in fruit, but relatively light in body, very high in acidity, and both of these are wines that tend to age very slowly over decades to reach full maturity, which is not typical to California. And it is because of the type of soil and microclimates that they're placed in.

There is also two and a half more acres, right next to the home vineyard. The home vineyard is a gentle slope, generally facing northeast, continuing north, and it drops further towards the north, and suddenly you're facing north. And we have recently, in the last eight years, been working on that two and a half acre site and we call this the White Field. It's not yet commercially released, but it's coming in the pipeline. And there we're focused on a field blend of about 11 different grape varieties. It's Sauvignon Blanc, Viognier, Roussanne, and Riesling and Syrah, and Pinot,and Trousseau and Mondeuse, and Counoise and Cinsault, so a whole bunch of different grapes. We pick them not completely randomly. We pick them by having at least a chance to withstand spring frost, which this site gets almost every year now, due to global warming. Also the soil type, which is relatively heavy, is a variation of the theme of decomposed granite, but it's not red clay, it’s sort of very dense and yellow, and it's really a decomposed serpentine rock, a granitic soil, but it's not one of the classic things that you think about when you think of wine. So, it’s a very interesting microclimate and soil combination and we saw that the palate of different grape varieties could have a better chance of succeeding in a place like this. It could be too challenging for one single grape variety. And also, if you think about it, what happens when you have a field blend, instead of one single variety, what comes to the surface in the wine is the essence of the terroir, because the grape varieties sort of cancel each other a little bit by the co-fermentation, and what comes to the surface is the character of the soil, which is really what we were hoping to happen.

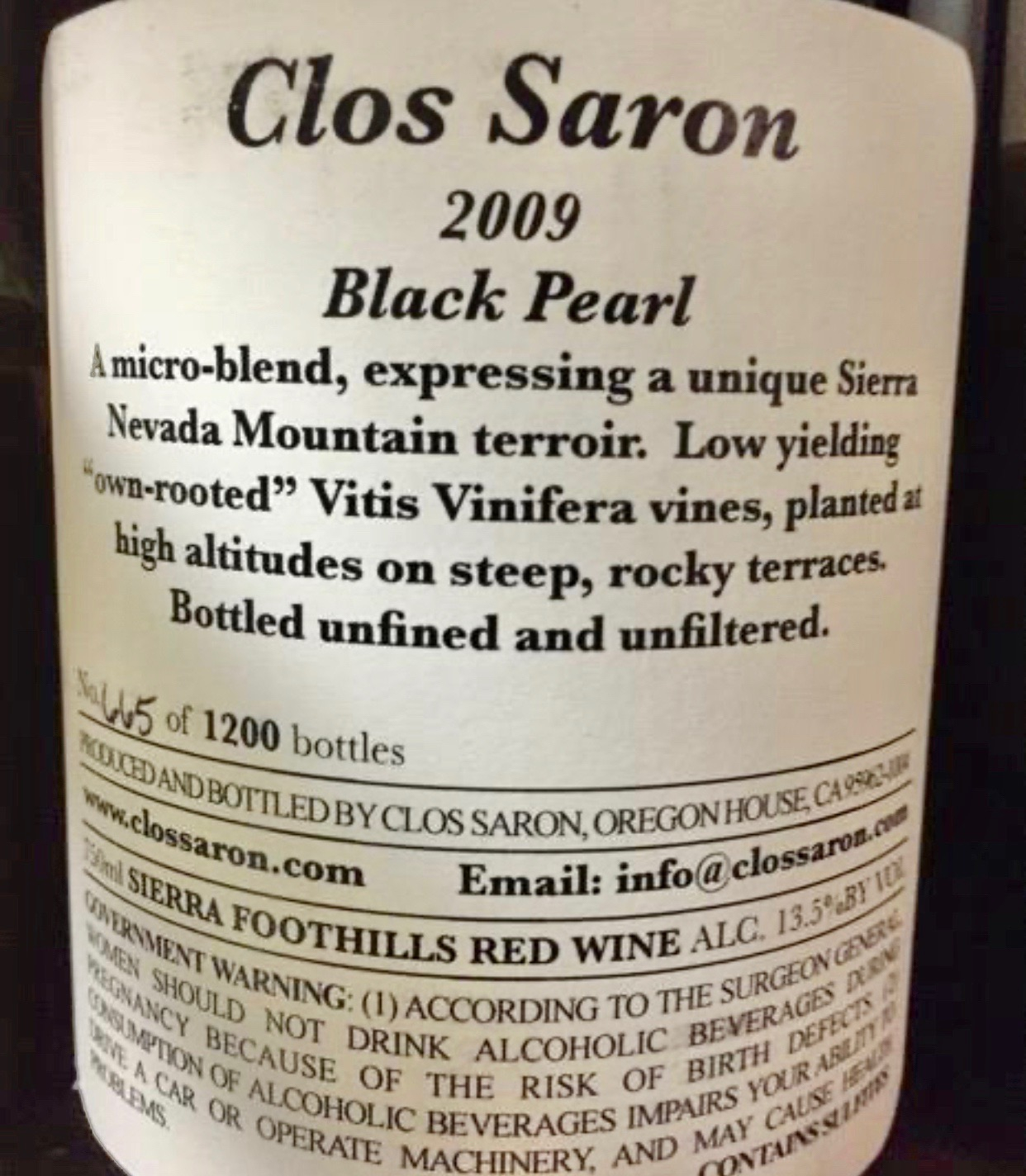

Can you tell us about your wine called the Black Pearl?

Can you tell us about your wine called the Black Pearl?

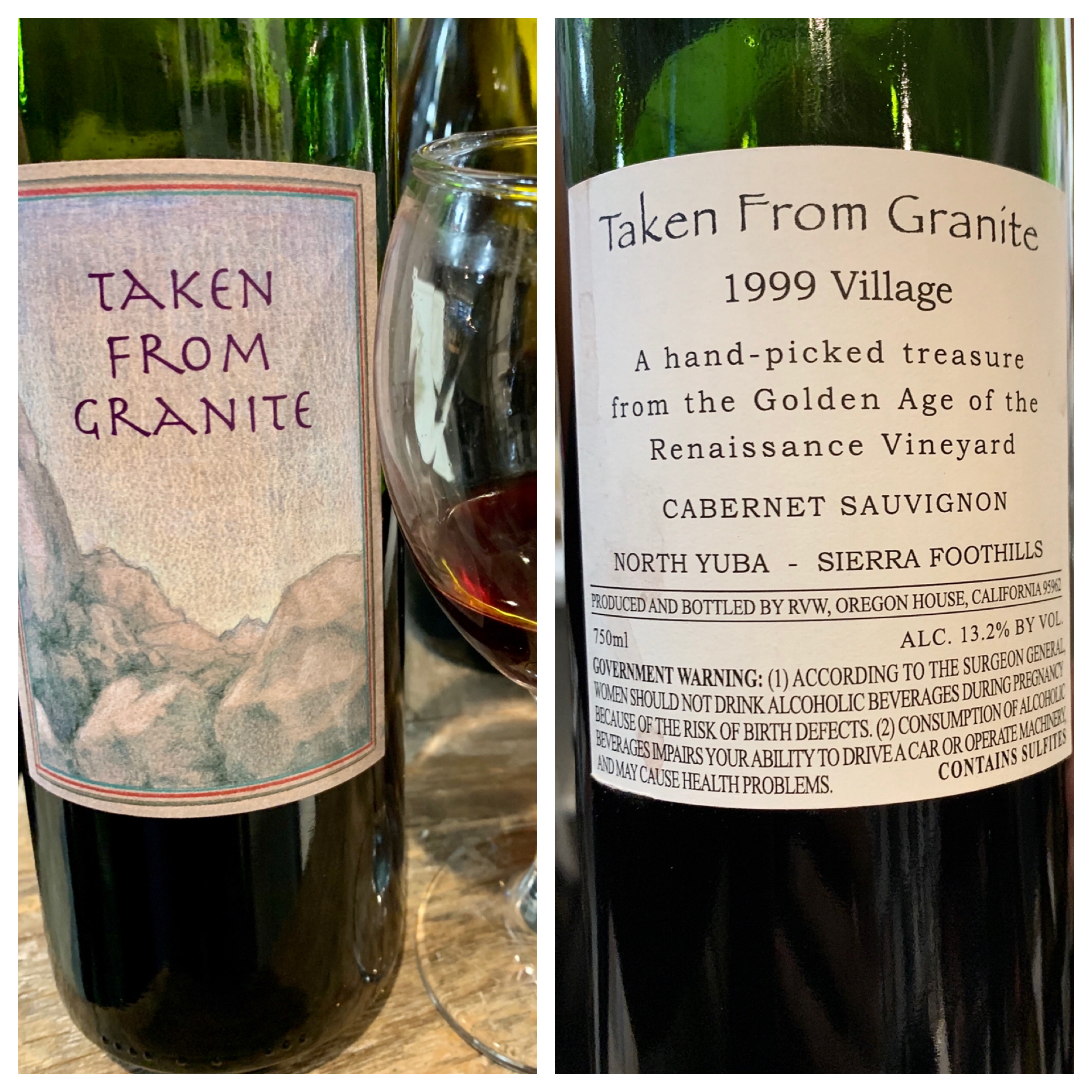

We started producing Black Pearl in 2000. It was a co-fermentation of Renaissance grapes, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah. Or I should say Syrah, Cabernet and Petit Verdot, and for better or for worse, it became one of our most popular wines — in part because of the name. Right after we started making this, a film came out, the whole, what is called ... Pirates of The Caribbeans. So suddenly people were going, "Oh, Black Pearl." So there was a lot of interest in this, and also because by character, this was one of the easier wines of ours to understand.

Our wines tend to be, by California standards, when they're young, relatively austere, a little rustic, angular, and more demanding. Not everybody can immediately understand them and get what's happening there or have the patience to age them until they become very refined and more expressive. Black Pearl had more richness to it, and it immediately was very popular with our customers. So it resulted, I'll say this now because later it's will become meaningful, it resulted from a couple of winery experiments at Renaissance when I was a young winemaker in ’93, ’94, and ’95. I experimented with as many combinations as I could think of that could lead to interesting variations on what Renaissance was doing because as we were proliferating the makeup of the vineyard in terms of how many grape varieties we were introducing by grafting onto less successful sites in the vineyard. I had to figure out what's the best use of these new varieties. So one of the experiments was co-fermenting Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon from one specific part of the vineyard, so from a specific terroir. That later led to the production of the Black Pearl because that was a very successful experiment. It didn't fit what Renaissance was doing so I decided to not make this for Renaissance, but for Clos Saron it was a perfect wine to make. So in 2000 we started taking that experiment further and that microclimate and that site was part of what we leased for Clos Saron in part because of these experiments. So we made Black Pearl from 2000 until I left in 2010.

In 2010, what happened that interfered with that, was that we had very, very severe spring frost. It pretty much wiped out all the Syrah production of ours, so we didn't make a Black Pearl. We took all the remnants, whatever there was and we made one wine out of this, one cuvée and we called it Spring Frost and released it two years ago. So, '09 was the last officially produced Black Pearl. Then we walked away and that ended.

In 2015, we got a phone call from Renaissance after we started harvesting our fruit, and that was a surprise, out of the blue, and they asked if we wanted to buy some fruit. And that's because that was the first time that they decided to go out of production. So I went, "Hmm, interesting." Typically, in a winery, you plan ahead your production. So I was limited in how much wine I could accommodate, but the temptation of going back and producing wines like the Black Pearl was too much. So I said, "Okay. Yeah." So from ’15, and then continuing ’16, our friends, Aaron and Cara from Frenchtown Farms, by then had an established contract, so we kept farming under their umbrella. So we made it '15, '16, '17 and '18 Black Pearl. By the way, these recent Black Pearls have not been released yet. Now my goal is to age them a little bit longer before releasing them even though we have a couple of vintages in the bottle. I prefer to hold them back and release them when they are at least seven or eight years.

We also make pure Cabernet Sauvignon from Renaissance in the same vintages, and that I would like to release when it's 12 years old because these ones really take their time, and for the main part, people nowadays, wine drinkers don't have the time to be bothered with aging wine and don't care so much and don't understand really what they miss by not having mature wines. So I'd like to at least take it to a place where people can recognize the full potential of these wines. In '19, we did not produce anything from Renaissance, but again, this year we were offered an opportunity, an idea that is floating around right now and we may make one more Black Pearl in 2020. I don't know.  Can you tell us about the Sierra Foothill AVA? It's quite a large area, correct?

Can you tell us about the Sierra Foothill AVA? It's quite a large area, correct?

It's very large. I don't know the numbers in terms of how many acres or how long it is. I would guess that it's roughly 200 miles long and somewhere in the neighborhood of 30 miles across, and even more, and it's nearly a meaningless AVA as it is right now because, in it, you have literally endless variations of microclimate, not quite endless variations of soil. The soils tend to be granitic in origin, but again, remember the granite is not one thing. People think of granite and some people think about the high Sierra, which is like salt and pepper, really white and black flakes. That's one granite, and then you have the countertop granite, which can be pink or can be green, or can be anything, black or brown, white. Each of these represent different chemical compositions, therefore, as it turns into soil, as it decomposes, it creates different soils that have different characters. So Sierra Foothills Ava is a mishmash of many things and it's not one thing. And people found there are at 1600 or at 800 feet elevation or 3,500 feet elevation, which are dramatically different in what that represents. Sierra Foothills came to be from the gold rush era, but as a commercial modern wine phenomenon, the first few wineries in the foothills sprung out in the mid seventies or so. Renaissance was one of the early ones, but it was not the only one. There were more further south. Renaissance is positioned a lot further North than most of the production area in the foothills.

And then, unfortunately, what was happening in the vineyard planting is that the Foothills did not attract the same level of financial investment, therefore not the same level of skill and ambition as say Napa did from almost the get go because Napa was closer to civilization. It was closer to San Francisco, it got a lot easier access and more money. The Foothills were started as a very backward and unambitious type of general climate and the way that the vineyards were planted was without a lot of thinking. What was king there was trying to plant vineyards for as little money as possible, and the easiest places to access and the places that would produce the highest yields. These are not good reasons for vineyard planting. So what it translates to is that a lot of the earlier vineyards in the Sierra Foothills, other than those planted by the gold rush era people, were unfortunately in high elevation flat areas, like valleys basically but slightly higher up, that had deep soils, more moisture in the soil, producing mediocre grapes. All in all, earlier Sierra Foothill wines were not inspiring. They were produced, because of lack of funds and ambition, by people who had sort of lower bars as far as what they were shooting for. So it established itself solidly as the poor cousin of the glitzy coastal range regions like Napa, Sonoma, and, then later, Central Coast, that attracted a lot more serious, ambitious people.

Has that changed?

It certainly is changing. I would say that in the last 15 years, especially in the last 10 years, two things happened. One of them is that there's been a huge influx of young blood into the wine industry. As the natural wine phenomenon has exploded on the east coast, and people started looking towards California and saying, "Does anybody there work this way?" And, "Oh yeah, there are a few. There's Tony Couturier, there's Gideon, and there’s…” At first, there were only like literally like a handful. Very quickly, as soon as there was any attention, other people started jumping in and saying, "Hey, we can do this. This is cool, this is interesting," And more and more young people started buying fruit somewhere, renting a garage somewhere, or a small warehouse, crushing, selling. It's very, very cost effective to do it this way. There's no farming. Farming is where all the labor and the cost goes. Making wine is very inexpensive. You don't need much, there's not much overhead, you don't much employees or anything. So a lot of people were drawn into this and things started happening.

So where do you buy fruit? If you go to the glitzy appellations, it costs a lot of money, so therefore you look elsewhere. So that's why suddenly areas like the Foothills or Mendocino or whatever, the fringes started attracting more attention. And at first, honestly, a lot of these natural wines were pretty lousy, but very quickly people were learning and getting more and more right, and then there's some very delicious wines coming out and then people would say, “Oh, it’s Sierra Foothills, Sierra Foothills is cool." Why? Because it's natural. So it all started feeding itself like a roller coaster, it started feeding itself and started growing. And suddenly now, Sierra Foothills is a cool appellation. So, great!

And do you have any sense as to what the future holds for the Renaissance property?

There are a few likely scenarios, and I really don't have a clue which one would happen. One of them is that it will disintegrate and that either there would be factions that will take over little sections of whatever, maybe fight over them, maybe not, or maybe subdivide. Or that things would be auctioned off, in which case these vineyards may survive or may not survive depending on what happens. Because by now it's not 365 acres of one massive vineyard, it's little vineyard here, a little vineyard there, and some of them are on the same parcel, some of them may be on a different parcel, because the whole property of the fellowship, which is somewhere around 1200 acres, is on a few different parcels and some vineyards are on different parcels. So it's difficult to predict exactly what will happen. I don't think that if it will be auctioned, I will be bidding on it. I'm too old for this stuff.

But during the last few years, it's sort of ironic. Because during the time that Renaissance was releasing whatever it was, 20 or 30,000 cases a year trying to sell them unsuccessfully, the general feedback that they were getting from the media and from the wine industry was suspicious, basically rejecting the wine. So the wines were never accepted, certainly not as fine wines. There were very few voices in the wine world and in the media that were saying, "Hey guys, this is something really special." It was a very small minority for decades, Matt Kramer was one single voice that in the world of the Spectator, for example, that was saying positive things. I mean, he made Renaissance his wine of the year like three times, I think in '91 '95 '97, different wines, they were his wine of the year, which is saying a lot. But, he told me early on, the Wine Spectator will never give you high ratings, ever, because these guys don't get it. It's like it cannot come on their radar.

But during the last few years, it's sort of ironic. Because during the time that Renaissance was releasing whatever it was, 20 or 30,000 cases a year trying to sell them unsuccessfully, the general feedback that they were getting from the media and from the wine industry was suspicious, basically rejecting the wine. So the wines were never accepted, certainly not as fine wines. There were very few voices in the wine world and in the media that were saying, "Hey guys, this is something really special." It was a very small minority for decades, Matt Kramer was one single voice that in the world of the Spectator, for example, that was saying positive things. I mean, he made Renaissance his wine of the year like three times, I think in '91 '95 '97, different wines, they were his wine of the year, which is saying a lot. But, he told me early on, the Wine Spectator will never give you high ratings, ever, because these guys don't get it. It's like it cannot come on their radar.

The style of wine and the story behind it. So it was no, it was taboo, and that characterizes the media response because yes, occasionally there was an isolated article somewhere that came and went and left no trace. Now, in the last five years, you look online and you find massive pontificating and poetry about the incredible value of Renaissance Cabernet Sauvignon and whatever. So now it's coming that, yes, there is a cult following there, of people that think that this is like no other California wine. I don't know if it's like no other California wine, but you know, I had an extremely solid wine education and I taste wine like a consumer.

I'm proud of my work, but I don't take credit for greatness in wine because to me that's the vineyard, because there's no greatness other than the vineyard in wine. So, to me, the best of the Renaissance wines are second to none. And it's incredible. I feel privileged to have been involved in this. And so whether people recognize it or not, I truly don't care that much. I mean, I prefer when people recognize it, of course, but if they don't, they don't. They have other things that they get excited about and that's good.

Read more about Renaissance Winery by Esther Mobley in the San Francisco Chronicle: "The Lost Civilization of California Wine."