Toward the end of his podcast “Wine & Hip Hop,” Jermaine Stone, who worked for two of our favorite wine stores for more than a decade, laid it out for the guests: “We’re experiencing an explosion, kind of like a black renaissance, in wine and culture.”

His guests, Sukari Bowman and Larissa Dubose, wholeheartedly agreed. Bowman, a banker in Atlanta, is host of the popular podcast “The Color of Wine” and co-creator of the website “Love and Vines.” Dubose, also of Atlanta, is a Certified Specialist in Wine and has been in wine sales and distribution for about 10 years. Her blog, “The Lotus and the Vine,” promises to bridge “the gap between the wine novice and the wine connoisseur.” Stone, a former rapper, is CEO of Cru Luv Selections, a Brooklyn-based wine importer and consulting company that also hosts wine education events. The three call themselves The Wine Avengers and they’re hosting a “Legends of the Fall” cool-weather wine tasting Sept. 22 at the Wine Gallery in Harlem and introducing their new podcast, called, well, The Wine Avengers.

(Photo: Sukari Bowman)

It may be happening at what some consider a glacial pace, but black people are occupying positions in the wine world unheard of only a few years ago, from Brenae Royal, 29, who manages the historic 575-acre Monte Rosso Vineyard in Sonoma; to Carlton McCoy Jr., 34, one of two African American Master Sommeliers and now president and CEO of Heitz Cellar; to Lawrence and Dorine Boone of Delaware, whose Lawrence Boone Selections imports wines from 20 producers in Spain, France and, they hope soon, South Africa; to winemaker Edward “Mac” McDonald, 76, who founded Vision Cellars in Windsor, Sonoma County, in 1995 with his wife, Lil, 70. As black-owned wineries go, Vision is a legacy enterprise.

Yet African Americans still are woefully underrepresented in the wine industry, across the board, which frankly is not very smart given their growing interest and their money. “That’s a lot of buying power,” Stone says.

Yet African Americans still are woefully underrepresented in the wine industry, across the board, which frankly is not very smart given their growing interest and their money. “That’s a lot of buying power,” Stone says.

(Photo: Lawrence and Dorine Boone)

So we reached out to some important African American wine people to ask: With all the talk about diversity, how are things at this point in the wine industry? And what needs to be done? Our exploration led us to some old acquaintances and new ones, all deeply committed to making the wine tent bigger.

We met André Hueston Mack around 2004, when he was head sommelier at Thomas Keller’s 3-Michelin-starred Per Se in Manhattan. Since 2007, Mack has made wine, especially Pinot Noir, and designed cool hip-hop and skateboard-influenced T-shirts, under the label Maison Noir Wines. Mack, 46, is based in Brooklyn but stays on the road making his wine in Oregon now with his team there and marketing it. He makes 40,000 cases a year and his wines are distributed in 47 states and 11 countries.

“I have to say that it’s sooooooo much better than it has ever been but there’s still a lot of work to do,” Mack wrote us in an email. “It’s just going to take time.”

Representation, highlighting blacks doing anything significant in the wine world – growing it, making it, selling it, serving it, enjoying it, writing about it, anything crucial in the chain -- is critically important, as is genuine inclusion, he and others like Julia Coney, a wine and travel writer in Washington D.C., said. “When you don’t see anyone that looks like you doing something you might be interested in doing, then one tends to think that it’s not for you,” Mack wrote.

(Photo: André Hueston Mack)

“There are challenges every day about being a black man in the wine business,” Mack said in a documentary called “Red, White & Black: An Oregon Wine Story,” which was executive-produced by Bertony Faustin of Abbey Creek Vineyard, who is regarded as “the first recorded black winemaker in Oregon.” Faustin, whose movie also spotlights a gay, white female winemaker and a Mexican-American one, took over his in-laws’ vineyard in 2007.

“People say, well, what difference does it make what the color is of the person who makes my wine? But we still need to continue the conversation because people are really still stupefied and dumbfounded when I show up,” Mack said in the film. In 2003, he became the first African American to win the title of Best Young Sommelier in America, conferred by the Confrérie de la Chaîne des Rôtisseurs, the food and wine society.

Bowman, Dubose and Stone all said Mack’s wines were the first they’d tasted made by a black winemaker. Our first were made by Brown Estate Winery, the first and only black-owned estate winery in Napa. Bassett Brown, a physician from Jamaica, and his wife, Marcela, purchased 450 acres in the Chiles Valley AVA in 1980 as a rural refuge for their three kids. At first, they sold their grapes, but in 1995, the kids, then young adults, decided they should bottle their own wine. They did, beginning in 1996 with an awesome Zinfandel. They were our guests at The Wall Street Journal’s Open That Bottle Night for vintners in Napa. With their parents retired, the siblings run the place now.

Interest in wine is evident and growing among African Americans – and, yes, wines other than Moscato, although that sweet wine and other sweet wines command the lion’s share of advertising dollars targeted to the black community, according to Dubose, 42, who is Level 3 WSET certified and statewide manager of sales in restaurants and bars in Georgia and South Carolina for California wineries JUSTIN and Landmark.

Interest in wine is evident and growing among African Americans – and, yes, wines other than Moscato, although that sweet wine and other sweet wines command the lion’s share of advertising dollars targeted to the black community, according to Dubose, 42, who is Level 3 WSET certified and statewide manager of sales in restaurants and bars in Georgia and South Carolina for California wineries JUSTIN and Landmark.

(Photo: Brenae Royal)

On Stone’s Wine & Hip Hop episode with LeA, known as the Granddaughter of Hip Hop, he “breaks down how to level up from Moscato by pairing Drake’s ‘Nice for What’ with a bottle of 1990 Suduiraut from Sauternes,” according to his website, wineandhiphop.com

Stone told us he founded his companies and named them carefully, Wine & Hip Hop and Cru Luv Wines, “to truly make wine more accessible, more relatable and to create our own wine culture. This is how we do wine tasting. But also make sure it’s not pandering and also not losing any reverence for the product. Always doing it at the highest level.” Thus the discussion of moving up from Moscato to Sauternes.

Representing wine brands, Stone told us he encounters some major hurdles. One is access, getting stores in minority communities to be open to carrying more diverse brands and styles of wine. ‘“Oh, my audience doesn’t drink this or this isn’t what my audience wants.’ It could be the sweetness level or the price point, a lot of different things. They say those things instead of thinking how they could grow their audience by switching things up. We’re not the ones who own these stores,” he told us. “And it’s not just with the retailers taking more responsibility to educate their audiences. Also it’s up to the brands to extend themselves to these areas.”

Black consumers also need to be more open to trying new things, he said, adding, “Some people say they don’t like Chardonnay because it’s thick and buttery so I say, try some French Chardonnay, some from the Jura. It’s important to start diversifying their choices.”

Black consumers also need to be more open to trying new things, he said, adding, “Some people say they don’t like Chardonnay because it’s thick and buttery so I say, try some French Chardonnay, some from the Jura. It’s important to start diversifying their choices.”

(Photo: Jermaine Stone)

Stone, 35, has a remarkable history. When he was 19, he left a promising career in rapping for a temporary job to earn money for college. That job was in the shipping department packing boxes for Zachys Wine Auctions in Westchester County. He was a hard-working quick study, learning about the handling of fine wine. The folks at Zachys noticed and kept promoting him so he gained experience dealing with clients, picking up consignments in Switzerland, managing auctions in Hong Kong, “meeting people I never would have met in the Bronx. This cultural exchange was happening because of wine and because they’d never got to meet a dude from the Bronx, which is why I try to talk about hip hop. It’s a global, cultural thing, our number one export,” Stone said on his show. He said he left Zachys after about 10 years, when he was logistics manager, tracking about $60 million in fine wine every year.

“I give Zachys a lot of credit. Everyone has preconceived notions. As soon as they knew I was talented they did everything to keep me happy, to push me forward,” he said.

In 2013, Wally’s in Los Angeles opened an auction arm in New York and hired Stone as one of its founding directors. After Wally’s, Stone said, he founded his business, consulting for the collectors, auction houses, warehouses and retailers he had done business with over the course of his career. “We live our mission statement: Blending wine & Hip Hop at the highest levels. I can be in the studio with a multi platinum producer one night and sell you rare Burgundy the next,” he wrote us.

Mac McDonald of Vision Cellars was one of three winemakers who founded the Association of African American Vintners. The Pinot Noir specialist is now president of the AAAV, which has 10 wineries and two growers as members. Among its associate and industry members are Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits, the largest wine and spirits distributor in the country, and giant E. & J. Gallo. There are 60 black-owned wineries worldwide, according to Marcia Jones, the creator of Urban Connoisseurs, a wine consultancy and event planner that’s leading a drive to provide scholarships to black students pursuing careers in the wine industry.

“The systemic issues facing African Americans aren’t going away soon,” McDonald wrote us. But “what I see is all nationalities are increasing their knowledge about wine. More African Americans are traveling to various wine areas and understanding the difference in wine and growing techniques. There are a number of groups that are sharing information among themselves, which has not been available in years past. Education is the key to appreciating wines.”

“We have a saying: All we want folks to do is enjoy wine. It does not have to be our wines, just find wines you enjoy,” McDonald wrote.

“As far as winemakers and vineyard owners are concerned, there is a growing need to be more educated about how the market system works,” he wrote. “There are many steps in becoming a true and successful winemaker. We need to keep looking for ways to market to all consumers.”

Derrick Westbrook, 32, a certified sommelier who has been beverage director at some of Chicago’s best restaurants and has his own consulting and events company, Derrick C. Westbrook, gives this advice on getting into the industry:

“You have to love it and treat it like a profession — like doctors, teachers. Treat it like those professions that we think of as prestigious. Look for the jobs in spaces where not a lot of you are and then when you get in those spaces, learn the jargon, learn the language and then create your own. Make sure that you’re genuinely yourself when you come into these spaces and then Robin Hood that shit — take everything you learned, everything you experienced, and bring it back and show someone else,” Westbrook told Black Food & Beverage magazine.

Hitting on the theme of getting educated in wine, Dubose had this to say:

“One can be hard-working but lack ‘polish,’ and this can get in the way of progress. Many business deals happen on the golf course and at restaurants. Not everyone can play golf, but everyone eats.

“I see too many people give a piece of their power away when the wine list comes to the table by giving the wine list to someone else. Culturally, we are not expected to know about wine. It's beautiful for me to watch what happens when we do what is not expected of us. It always gets attention. I want more of us to have that power.”

Shields T. Hood, general manager of the Society of Wine Educators, said that although it doesn’t track the race or gender of people seeking its certification, he’d guess the number of African Americans is about two to seven percent, depending on the level of certification. “We believe we are seeing an uptick in African Americans attempting our exams.”

A spokeswoman for the Sommelier Society of America wrote, “As SSA is NYC-based, our classes are highly diversified; but our applications do not request race or ethnicity information so we do not have that data.”

A spokeswoman for WSET, the Wine & Spirit Education Trust, said it had no information about the race of its students.

“Today there are definitely more affluent people of diverse backgrounds who want to support emerging winemakers and other wine industry professionals than there have been in the past. And these people are hungry for information,” said Judia Black, founder in 2008 of enJoie, a New York-based food, wine and lifestyle media, events and gifts company. Certified a sommelier by the American Sommelier Association, she also has completed the level 3WSET course and holds an MBA.

“Today there are definitely more affluent people of diverse backgrounds who want to support emerging winemakers and other wine industry professionals than there have been in the past. And these people are hungry for information,” said Judia Black, founder in 2008 of enJoie, a New York-based food, wine and lifestyle media, events and gifts company. Certified a sommelier by the American Sommelier Association, she also has completed the level 3WSET course and holds an MBA.

(Photo: Judia Black)

Black is also an Ambassador for the Boisset Collection, where people get commissions for selling wines made by Jean-Claude Boisset’s family enterprise, sort of like modern-day Avon ladies, hosting tastings sometimes in their homes. Boisset’s organization told us a growing number of these independent “ambassadors” are African Americans, probably five to seven percent.

We first came across Black’s ambassador work when she invited us in July to meet Theodora Lee, a trial lawyer who owns Theopolis Vineyards, an 800-case winery in the Yorkville Highlands of Anderson Valley in Mendocino County. While Boisset wines were poured in enJoie glasses in one part of the room, Lee was holding court in another. Lee told us she planted her vineyards in 2003 and at first sold her grapes to a winemaker who scored high numbers from Robert Parker with her fruit. In 2014, she decided to make wine herself and paid a winemaker with half her fruit to make it to her specifications. Today, using a winemaker, she sells her wine direct-to-consumer.

“Practically nothing can happen in my life without me being involved,” she told us, explaining her part in the winemaking. “Life is about bringing it and under pressure doing it and enjoying it. It’s a pleasure beyond anything I could imagine.”

Some African American wine lovers have embraced a mantra from the late Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm: “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”

Melody Fuller, a wine, food and travel writer, said she was treated badly on her first trip to Napa in the mid-1990s but welcomed warmly in Europe.

Melody Fuller, a wine, food and travel writer, said she was treated badly on her first trip to Napa in the mid-1990s but welcomed warmly in Europe.

(Photo: Melody Fuller)

“Most of my time had been spent in Sonoma County, where I was welcomed and treated with abundant hospitality with a few searing, unpleasant exceptions,” she wrote us. In Napa Valley, “I was interrogated, a suspect, disrespected and treated in ways that left me feeling like an unwanted intruder or worse. There were exceptions. However, when your feelings are hurt and your smile not returned, you fade away and try your best to leave the negative impact behind. So that is what I did for many years, until I returned to the Napa Valley several years ago.”

She went back several times and found Napa Valley changed. In 2015, hewing to the idea that everyone should feel welcome around wine, she founded the Oakland Wine Festival, an annual event that brings winemakers from Napa, Sonoma and around the world to Oakland to meet and pour their creations for wine lovers of every kind. It was “the direct result of hours-long conversations with Michael Silacci, winemaker for Opus One; Russ Weis, president of Silverado Vineyards; and K.R. Rombauer, III, with Rombauer Vineyards,” she wrote us. “I consider these three wise men my three wine-kings as they are also very good and dear friends.”

Fuller wrote that with her events, she helps support several area charities. Last year, she started “The Exceptional Vine Initiative,” which she described as a global effort to bring youths of all ethnicities and races “into this multi-billion-dollar industry that is, simply said, not diverse.”

Others have seized another way: “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, build your own table.” There has been steady growth in events open to everyone, of course, but geared especially to black wine lovers and black winemakers. In 2011, Fern A. Stroud, an IT software development project manager for more than 20 years, founded a now annual event in Oakland called Black Vines that celebrates black artists, musicians and winemakers.

Benita Johnson of The Vine Wine Club hosts an annual four-day happening called the Exclusive Blacklist Event in Richmond, Va. It’s where Bowman met some “amazing people,” confirming that she and her brother, Shomari, a chef and music lover, were on the right track in developing The Color of Wine podcast and website, loveandvines.com.

“Once we got into the podcast we realized that we are creating an oral history of people of color in this industry,” she said. Bowman interviewed Dottie earlier this year, and has now interviewed 68 guests.

Bowman, 48, wrote that while she has seen progress, “there are still situations happening where at a tasting or industry event, we are being mistaken for ‘the help’ or ‘the Assistant’ or ‘The sweet-wine-only drinker’ or ‘just the tag-along, uneducated friend.’ I have a great deal of anger around these situations, but what really frustrates me is the number of times that these things happen and the overall lack of empathy and sensitivity.

“I have come to realize that I cannot control what other people think and how they act. I can only control my reaction. Sometimes that is easier said than done but we have to keep showing up at these tastings and industry events. We have to keep learning and growing. We have to keep bringing each other into these spaces with the hope that it will get better.”

She also suggests consumers ask merchants and restaurant wine directors to sell fine wines made by blacks, adding that fans can also use their networks to help winemakers get financing so they can grow. “We have to buy each other’s products, show up for each other at events, at speaking engagements and at tastings.

“Everyone talks about having a ‘seat at the table’ in this industry and I think that is important,” Bowman said. “But what many people miss is that sometimes we have to build our own table first. You never know, our table may become ‘The Table.’”

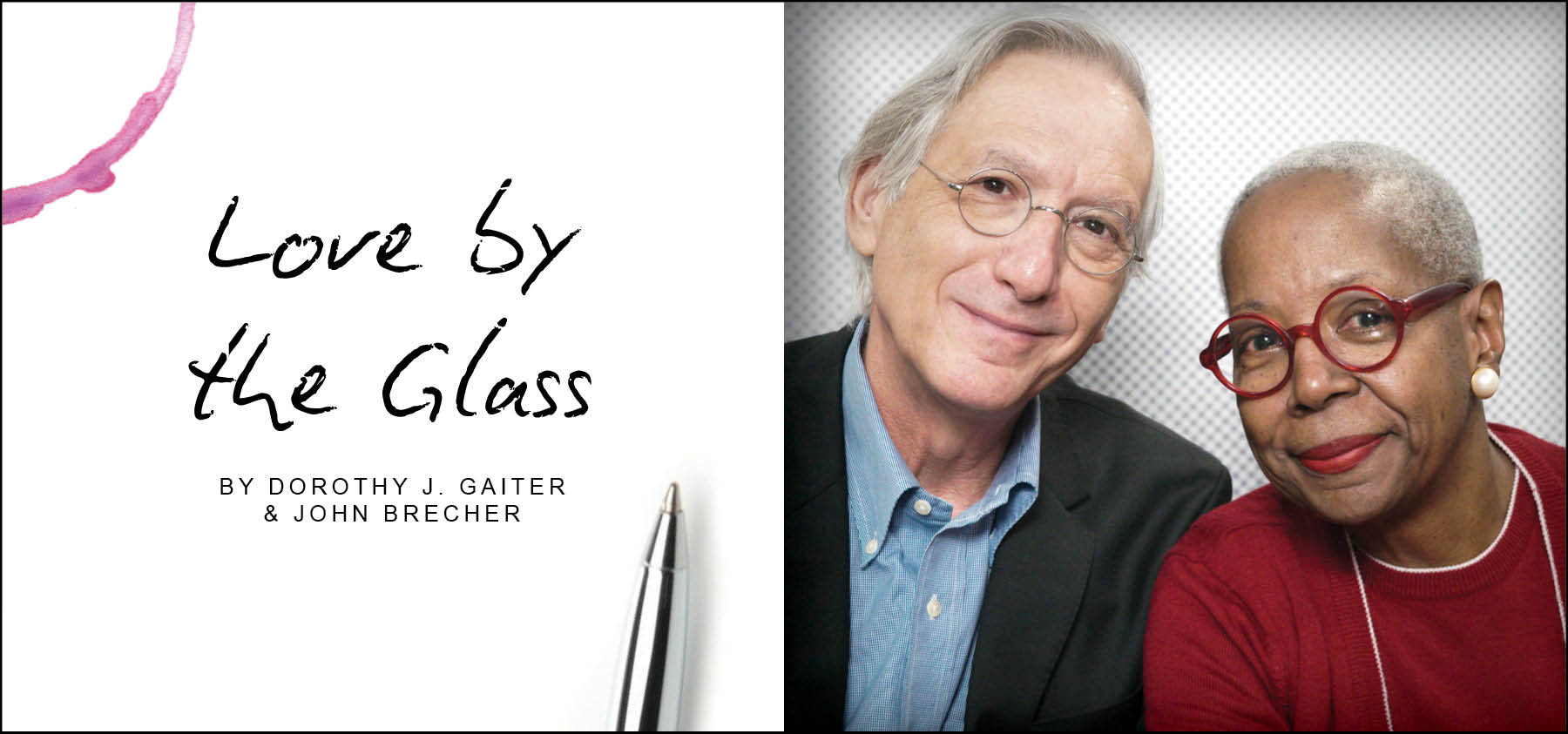

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective