Universum | Dok.Film: Zweigelt - Wein und Wahrheit from twovisions & rocket media on Vimeo.

Old news in a new light

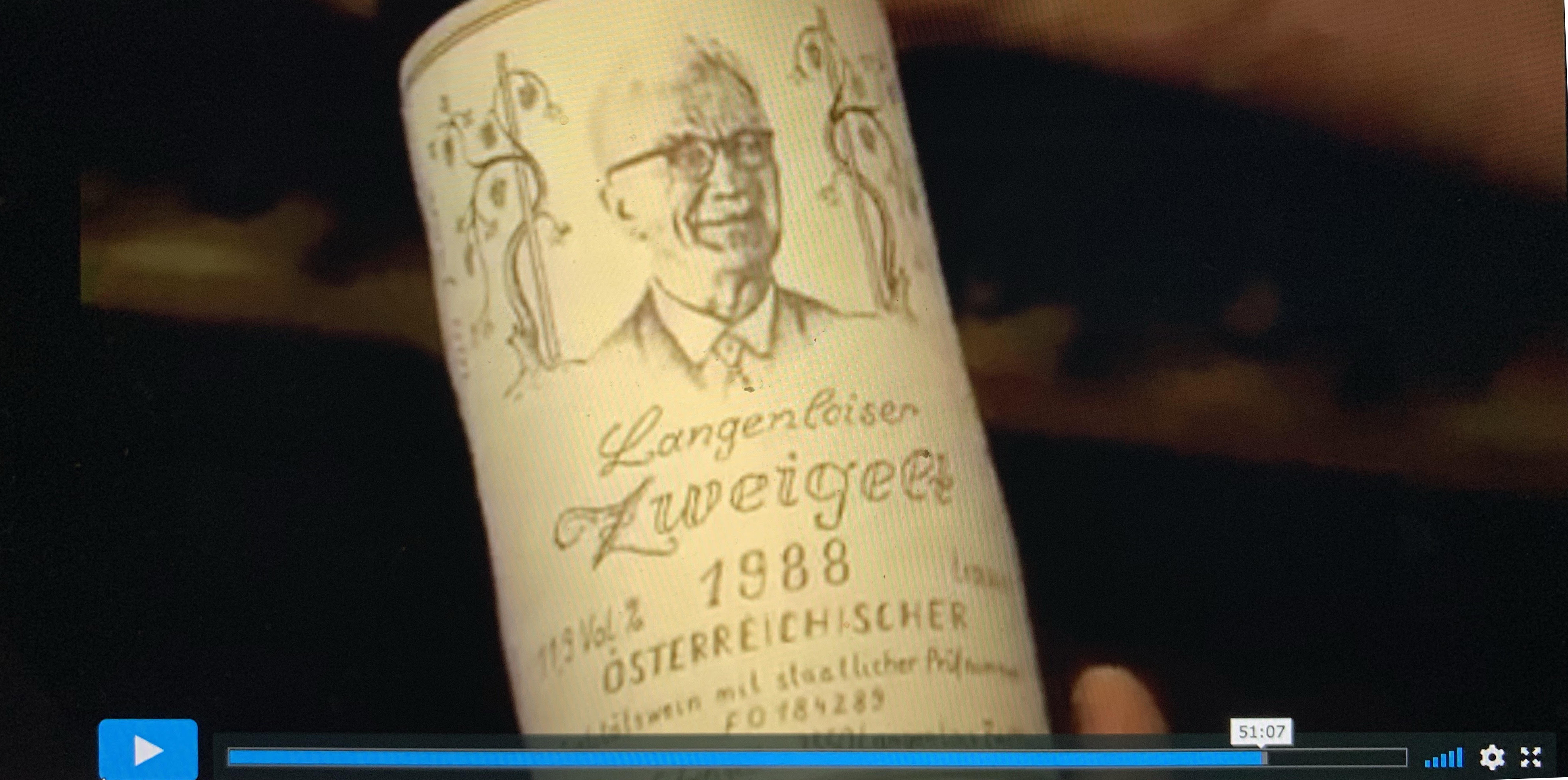

A grape breeder succeeds beyond his most vaunting ambitions, creating a variety that goes on to become the most planted red wine grape in his country. Eleven years after his death, the grape is given his name: Zweigelt, for Dr. Friedrich Zweigelt, a crucial contributor to Austrian viticulture — and, recent scholarship has verified, an early, active, and enthusiastic Nazi.

This is not a new story. Accusations have hung in the air for years. In 2011, a documentary film “Zweigelt — Wein und Wahrheit” (“Zweigelt — Wine and Truth”) took a long, hard look at the evidence of the viticulturist's allegiance to Nazism. Articles on the subject periodically surface in the German-language and international press. There is even an Austrian performance art group that seeks to raise awareness of the need to “free a fine wine from its unfortunate namesake.”

I first learned of Dr. Zweigelt’s dark past in January, when I read Jason Wilson’s lively and provocative book Godforsaken Grapes. In it, Wilson devotes a few pages to his own shock at finding Dr. Zweigelt “confirmed as a Nazi” and the not unjustified worry "that this would have a similarly disastrous effect as the 1985 antifreeze [in Austrian wine] scandal.” Then, in May, I attended a conference in Vienna hosted by the Austrian Wine Marketing Board (AWMB), and was impressed to see Wilson’s work echoed in the agenda. Within the scope of a forthcoming comprehensive history of Austrian wine, Willi Klinger, head of the AWMB, had moved to confront allegations directly by commissioning historian and journalist Dr. Daniel Deckers to conduct the first scholarly examination of Dr. Zweigelt’s life and work. This was a bold move for the AWMB, which represents the interests of Austrian wine producers. As Klinger told Falstaff magazine late last year: “I’m ruling nothing out and am very open. But [the decision about the grape’s name] may not be allowed to rest on conjecture.”

At stake, on the surface at least, is what, now, to call the Zweigelt grape. Currently, Austrian wine law lists the grape’s official name as Zweigelt, with the variants Blauer Zweigelt and Rotburger also permitted on labels. This has landed growers in a situation in which their labeling decisions take on the weight of political acts.

The case for, and against, Dr. Zweigelt

At the Vienna conference, Deckers presented his findings, which consitute the most comprehensive investigation of relevant historical records to date, including archival materials never previously examined and Dr. Zweigelt’s personal papers. The result is an unsettling portrait of an ambitious scientist whose politics ultimately undid his career, but not his legacy.

Friedrich “Fritz” Zweigelt was born in 1888 near Graz, in the then far-reaching Austro-Hungarian Empire. With an early love of natural sciences, he went on to earn a doctorate in botany and zoology. In 1921, he gained an opportunity to head a new viticultural research station at Klosterneuburg, the prominent oenology school near Vienna. There Dr. Zweigelt’s career flourished. He led an influential wine journal, authored countless articles, and travelled throughout central Europe to promote improvements in wine growing. Central to his work was Klosterneuburg’s grape breeding program, the aim of which was to create new varieties specifically suited to Austrian growing conditions.

Like most R&D, grape breeding is notoriously hit or miss. Very few attempted crossings produce a variety that succeeds commercially. But Dr. Zweigelt hit on a bankable winner within just a year: a cross of the indigenous Austrian grapes Blaufränkisch and Sankt Laurent. Its appeal to growers was — and is — its reliability as a late budder and early ripener, its cold hardiness and potential for high yields, and the bright, juicy, peppery wines it gives, well adapted to being made in a range of styles and blends. Dr. Zweigelt named the grape Rotburger, a red (rot) grape from Klosterneuburg — whose reputation, not incidentally, he sought to highlight as much as his own, per Deckers.

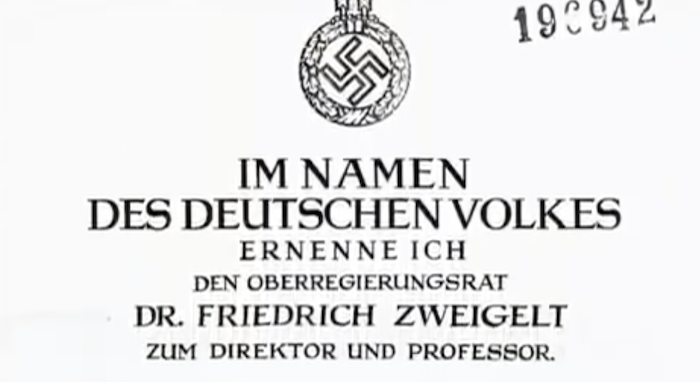

This work was, of course, taking place against the gradually darkening background of financial, societal, and political disintegration of interwar Austria. It was a place of dramatic collapse and reformation extending to identities and ethnic loyalties. Some Austrians, including Dr. Zweigelt, found reassurance and hope in German Nationalism. Although the Nazi Party (NSDAP) was still outlawed in Austria in May 1933, Dr. Zweigelt eagerly signed on as an illegal member.

When Austria was subsumed into the German Reich under Hitler in spring 1938, one of the first moves of the local NSDAP was to “instantly" appointed Zweigelt head of the research Institute, Deckers notes. “In April of that year, Zweigelt wrote, “‘Klosterneuburg can, must and will return to its previous greatness and will be worthy of its current mission in the Greater German Reich.’” To this end, Dr. Zweigelt collected damaging information about colleagues that led to a staff purge, and, together with other likeminded leaders of the school, set the tone for Klosterneuburg to become “a National Socialist stronghold within a few years,” as Deckers points out in a recent related piece on JancisRobinson.com. Nevertheless, his ambitions for himself and the school he eventually came to lead, did entangle him in conflicts with Nazi higher ups and Deckers reports some ambiguities in the record of Dr. Zweigelt's relationships with what can only be seen as anti-Nazi figures. Still, throughout the war, Dr. Zweigelt held tight to his leadership of Klosterneuburg and his Nazi loyalties, even when his only son was killed in East Prussia in 1944. Throughout this period, Dr. Zweigelt's writing maintained a tone that Deckers characterizes as “the prose of a die-hard National Socialist.”

For Austria, the death of National Socialism came with the Soviet Army invasion of June 1945, though some of its adherants were granted a curious afterlife. Dr. Zweigelt was arrested and interred, charged with treason, warmongering and denunciation. He protested, portraying himself as a “mere ‘follower,’” but the local police concluded: “‘Fritz Zweigelt was an agitator and informer on a large scale, who shied away from nothing to advance himself professionally [...].’” Yet, just six months later, he was released. By February 1948, he had been recategorized as a “‘lesser offender’” and a previous notice demanding his removal from the public sector was revoked. Later that year, Deckers reports, Dr. Zweigelt requested a pardon from then Federal President Karl Renner; the charges of “warmongering” were reduced to “‘oratorical lapses.’” Dr. Zweigelt eventually moved quietly to Graz, where he comfortably lived out his remaining years on a restored pension. He died of natural causes in 1964.

Enter Lenz Moser, another prominent 20th-century Austrian viticulturist. He was in the business of selling vines and particularly appreciated Rotburger’s adaptability to a vine training system of his devising as well as to the climates and soils of virtually all Austrian wine regions. Moser also admired Dr. Zweigelt and believed Zweigelt to be the more memorable name for this promising grape. In 1960, he began selling propagated vines under the name Blauer Zweigelt and it was he who agitated for the name to be adopted at an official level. In 1975, "Zweigeltrebe Blau" was included in the official index of quality wines in Austria — fully ignoring Dr. Zweigelt’s past and politics.

Today, Zweigelt surpasses all other red varieties — international and indigenous alike — in total vineyard area planted in Austria (6,426 hectares, or nearly 14%). It is grown in every one of the country’s wine regions and even has its own DAC, or designation of protected typicity and origin. This is a stunning achievement for a grape that did not exist a century ago, especially given the arc of Austria’s viticultural history, which stretches back to Roman times. But Austria is a tiny country, whose population barely exceeds that of New York City. Wine is grown only in the eastern half of the country, and the grapes for which Austria is known are hardly mainstream. This makes Austrian wine in general something of a niche, so producers have invested greatly in establishing the identity of grapes such as Zweigelt in export markets. Lately, Zweigelt wines have gained more of a presence in urban U.S. markets, and have begun to develop of following elsewhere as well. All in all, this leaves Austria with, as Deckers noted in his presentation in Vienna, “quite a big elephant in the room.”

Austrian producers weigh in

Critic and author Stuart Pigott, who specializes in German and Austrian wine, noted that “back in 1975, Austria was lagging far behind Germany in confronting the Nazi period, indeed it only seriously caught up in recent years and this is the indirect reason for all the fuss. Legally enforcing the name change is something I shy away from, not least because Zweigelt is now so well established. [...] Open discussion of the whole subject strikes me as more important.”

Taking that discussion to the wine growers and makers themselves, I contacted more than 20 Austrian Zweigelt producers, either directly or through their U.S. importers. At press time, eight had responded. (In fairness, beyond the sensitivity of the subject, the period of my research collided squarely with harvest, when wine growers are at their busiest.)

The overarching reaction among producers was to acknowledge the problem of Zweigelt, but also the practical complexity of changing the name of their country’s most popular and recognizable grape. This is the sentiment of one of Austria’s leading Zweigelt producers, Christina Netzl (photo, left), who, together with her father, runs Weingut Franz & Christina Netzl in Göttlesbrun, in the Carununtum region, just east of Vienna. She expressed what she described as “Two different views, thoughts, and opinions [...] on this topic — each, however, that I regard separately.” On the one hand, she said she finds it “extremely important [...] to bring to light the whole, unvarnished truth about Dr. Zweigelt as a person” and to confront "the deplorable and awful" acts of the Nazi regime "that are, regretably, a large part of our history in Austria." On the other, “I see it from the enological side – Zweigelt is a fascinating variety that yields terrific wines in our region. It is, for us, far and away the most significant variety and its great bandwidth for various styles is unique. We (all Carnuntum vintners, collectively) have worked very hard for many years on the reputation of the Zweigelt grape and to establish the variety in the most varied markets and most varied niches. The great importance [of this grape] to us would make a renaming immensely difficult for all vintners here in Carnuntum.”

The overarching reaction among producers was to acknowledge the problem of Zweigelt, but also the practical complexity of changing the name of their country’s most popular and recognizable grape. This is the sentiment of one of Austria’s leading Zweigelt producers, Christina Netzl (photo, left), who, together with her father, runs Weingut Franz & Christina Netzl in Göttlesbrun, in the Carununtum region, just east of Vienna. She expressed what she described as “Two different views, thoughts, and opinions [...] on this topic — each, however, that I regard separately.” On the one hand, she said she finds it “extremely important [...] to bring to light the whole, unvarnished truth about Dr. Zweigelt as a person” and to confront "the deplorable and awful" acts of the Nazi regime "that are, regretably, a large part of our history in Austria." On the other, “I see it from the enological side – Zweigelt is a fascinating variety that yields terrific wines in our region. It is, for us, far and away the most significant variety and its great bandwidth for various styles is unique. We (all Carnuntum vintners, collectively) have worked very hard for many years on the reputation of the Zweigelt grape and to establish the variety in the most varied markets and most varied niches. The great importance [of this grape] to us would make a renaming immensely difficult for all vintners here in Carnuntum.”

Despite these challenges, a handful of producers have dropped Zweigelt in favor of Rotburger on their labels. Hannes Schuster of Weingut Rosi Schuster, in St. Margarethen, and Stefan Wellanschitz (photo, right) of Kolfok Weine, in Neckenmarkt, have already changed their labeling. Schuster explains, “2015 was our first vintage officially called Rotburger. In fact, we knew who Mr. Zweigelt was and what he did, but we didn’t blame the grape for that. But once it was known to us that this variety was originally called Rotburger and that it was only renamed in the 1970s as part of Austrian wine politics, the name Zweigelt was no longer acceptable to us.” Wellanschitz takes a harder line: “Everyone who reads the name of this variety should know that Dr. Zweigelt was a devout, staunch National Socialist,” adding, “I see myself as responsible for explaining to people that the name ‘Zweigelt’ should be correlated one to one with National Socialism. That almost no one has heard of the synonym, Rotburger, can be discussed — a historical explanation can come out of ignorance. [...] I support an official renaming — in the name of Austrian history.”

Despite these challenges, a handful of producers have dropped Zweigelt in favor of Rotburger on their labels. Hannes Schuster of Weingut Rosi Schuster, in St. Margarethen, and Stefan Wellanschitz (photo, right) of Kolfok Weine, in Neckenmarkt, have already changed their labeling. Schuster explains, “2015 was our first vintage officially called Rotburger. In fact, we knew who Mr. Zweigelt was and what he did, but we didn’t blame the grape for that. But once it was known to us that this variety was originally called Rotburger and that it was only renamed in the 1970s as part of Austrian wine politics, the name Zweigelt was no longer acceptable to us.” Wellanschitz takes a harder line: “Everyone who reads the name of this variety should know that Dr. Zweigelt was a devout, staunch National Socialist,” adding, “I see myself as responsible for explaining to people that the name ‘Zweigelt’ should be correlated one to one with National Socialism. That almost no one has heard of the synonym, Rotburger, can be discussed — a historical explanation can come out of ignorance. [...] I support an official renaming — in the name of Austrian history.”

Franz Weninger (photo, left), of Weingut Weninger in Horitschon, points out that the discussion “reminds us that we have never entirely worked through our history. In reality, no Austrian is in a position to judge Mr. Zweigelt, as we were all accomplices. What should, however, be clear, is a distancing from this period.” He sees the argument in favor of changing the name being “that Austria sends a clear, loud signal in relation to this period.” On the other hand, “I, personally, don’t want to pass judgement on Mr. Zweigelt, as this is and was an Austrian problem, and does not only affect Zweigelt.” Weninger also noted the danger that “in Austria [changing the grape name] would, politically, supply material for some parties and needlessly fuel day-to-day and Stammtisch politics.”

Franz Weninger (photo, left), of Weingut Weninger in Horitschon, points out that the discussion “reminds us that we have never entirely worked through our history. In reality, no Austrian is in a position to judge Mr. Zweigelt, as we were all accomplices. What should, however, be clear, is a distancing from this period.” He sees the argument in favor of changing the name being “that Austria sends a clear, loud signal in relation to this period.” On the other hand, “I, personally, don’t want to pass judgement on Mr. Zweigelt, as this is and was an Austrian problem, and does not only affect Zweigelt.” Weninger also noted the danger that “in Austria [changing the grape name] would, politically, supply material for some parties and needlessly fuel day-to-day and Stammtisch politics.”

Alex Koppitsch of Weinbau Alexander Koppitsch in Neusiedl am See believes “It is impossible to erase the past and why should we? Talking about the name Zweigelt, because this doctor was a Nazi, sounds to me a little like one would like to try to cover the past, Nazi-Germany/Austria, etc. We keep the name, we keep reminding people of these terrible years. And that’s a good thing. [...] Right now, we use the term Zweigelt in all our tech sheets and wine descriptions. Why? Because it is the commonly known term for this variety. If we used Rotburger, right now, I would have to use the term Zweigelt to explain what Rotburger is.”

Heidi Schröck of Weingut Heidi Schröck in Rust explained her thinking: “I am really disgusted about everything [that] happened in our country in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s. But it is part of our history and eventually we have to learn and care that it never ever happens again. [...] I believe that I do not help anything and anyone if I called my Zweigelt now Rotburger.”

Schröck's stance was echoed by Judith Beck (photo, right) of Weingut Judith Beck in Gols, who noted: “Of course it is in bad taste to put up a monument to someone of unequivocal National Socialist thinking. On the other hand, the name is now established and known and, ultimately, changing the name doesn’t change history.”

Schröck's stance was echoed by Judith Beck (photo, right) of Weingut Judith Beck in Gols, who noted: “Of course it is in bad taste to put up a monument to someone of unequivocal National Socialist thinking. On the other hand, the name is now established and known and, ultimately, changing the name doesn’t change history.”

Selling “Rot Burger” to Americans

One of Austrian wine’s biggest advocates, the influential importer Terry Theise said he had "known for a long time that Zweigelt had an unsavory past." He made a strong case for the issue to be addressed by Austria's wine board, rather than be worked out by individual producers: “While ‘Zweigelt’ is not an especially euphonious name (leaving aside the moral ramifications), I think ‘Rotburger’ is even worse, simply from the selling standpoint [...] Life is hard enough selling Austrian reds without trotting through the market with something called ‘Rot Burger.’" But "the problem with letting growers decide this for themselves is the great potential for virtue-signaling and moral grandstanding on the part of those who were the first to make a change. It would effectively force the others to follow suit, and to explain why they had to be ‘embarrassed’ into doing so. That’s why I’d rather it were decided officially -- whichever way it was decided.”

Theise was one of 12 importers of Austrian Zweigelt wines I contacted, five of whom declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment. But among those who did, several noted that this inquiry was the first they’d heard of Dr. Zweigelt’s Nazi affiliations. Reactions spanned a range, from Savio Soares, who said this was not an issue among the producers he works with (“Zweigelt it is!”) to Emily Schindler of Winemonger, who took cultural contexts into consideration, mixing them with her own strong convictions. Her company imports Schuster and Kolfok, both of whom have, as noted, already changed their labelling. “I only learned of [the Zweigelt issue] just over a year ago from Hannes Schuster,” Schindler said. “Knowing the story, I personally feel the change should be made, particularly in light of the current culture and uptick in anti-semitism… With little changes like the name of a grape, a conversation gets started [...] I don't judge the winemakers I work with about whatever choice they make in this debate…” She added that she also understood “the concern that people won't know that Rotburger is Zweigelt and sales will go down.” Still, “as an importer of the wines,” she said, “I'm willing to take the hit because I believe it will be temporary, if anything at all, and worth it.”

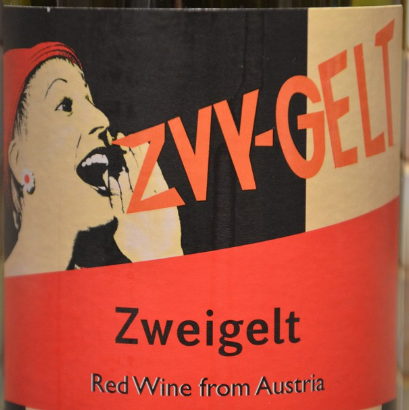

Renaming Zweigelt would bring about a very visible change for importer Monika Caha, whose portfolio includes two own-label wines, one of which features a phonetic spelling of Zweigelt being shouted across the bottle. She was resigned to an official determination: “In general we are all waiting for the wine marketing [board] to make a decision on how they want to proceed. People have been talking about changing the name for a long time, but obviously there have been many ideas of which name to take.”

Zev Rovine, who brings in a Rotburger from producer Michael Gindl, commented, “I think that Austrians and Germans are constantly dealing with how their history affects their current culture and it seems to me at this point they are mostly recognizing it and just living with it. I don’t think there is a big pressure to purge everything that was connected to WW2 and the [H]olocaust. With regards to Dr. Zweigelt, wasn’t almost everyone associated with the Nazis? [...] As a Jewish person importing Austrian wine, the topic of the [H]olocaust has certainly come up [with producers] and they seem to be open to discussion.”

The way forward

As this article went to press, a commission of historians was at work in Austria, evaluating Decker’s findings. The group is charged with formulating recommendations and presenting them to the Austrian wine industry. A report is expected in December. It is a credit to the investigative spirit of Willi Klinger and the responsible, resourceful research of Dr. Daniel Deckers that the historians are now well equipped to make their determination. Of course, the outcome will not be a mandate that Zweigelt be ripped up and replanted to something less controversial. The grape will remain integral to Austria’s wine culture and to the individual livelihoods of Austria’s growers. For now, the name Zweigelt stands, a reminder of the need to confront broader issues of complicity and resistance, past and present, right up to our own fraught moment.

Author's Note:

October 6, 2019

After publication of this article, Willi Klinger, head of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board, informed the author that one of the key findings in the — as yet unpublished — scholarship by researcher Dr. Daniel Deckers is that "'Zweigeltrebe' and then 'Blauer Zweigelt' were the first official names given to the cross St. Laurent x Blaurfrankish Nr. 71” and that the name Rotburger was added only in 1978. In follow-up correspondence with Dr. Deckers, he said despite the many sources that claim otherwise, "The Rotburger story is just a fairy tale -- unfortunately. I do not know who invented it." He goes on to say "the name Rotburger came into (legal) force as late as 1978 (created in and by 'Klosterneuburg'), I suppose that was not used officially or even colloquially before." He added that his research indicates the name "Zweigeltrebe" was first included in the official index of quality wines in Austria in 1972, not 1975 as all other published sources have it. Dr. Deckers will publish these findings in a forthcoming book

Sources and images:

Most of the biographical and historical details of Dr. Zweigelt's life presented in this article are drawn from Dr. Daniel Decker’s research, a summary of which can be read here .

“UMFRAGE: Soll der Zweigelt umbenannt werden?,” Joachim Riedl. Falstaff, December 12, 2018

"The Strange Case of Professor Zweigelt," Dr. Daniel Deckers, jancisrobinson.com August 15, 2019

"Zweigelt -- Wein und Wahrheit," Gerald Teufel, Director, twovisions & mediafilm, 2011

Monika Caha Selections http://www.mcselections.com/index.php?id=258

Email interviews (English and German) with producers and importers, conducted in August and September 2019

Special thanks to Christopher Barnes and Lisa Denning for their editorial support on this piece.

Homepage banner by Piers Parlett.