TRENTINO, Italy --“I just visited (foreign wine region) and had the most delicious wine I’ve ever tasted and the winery can’t get its wine imported into the U.S.! How could this be?” If we had a nickel for every time we’ve heard that, we could buy a bottle of Jay-Z’s new Champagne.

With better winemaking techniques and knowledge, fine wine is being made all over the world today. But as California winemaker John Skupny once told us, “It’s a whole lot easier to make wine than it is to sell it.”

Today’s case in point – and this is important to remember as we enter high season for sparkling wines – is Trentodoc, from mountainous northern Italy. Not familiar? Well, that’s our point. Fifty-five wineries there – in Trentino, surrounded by the spectacular Dolomites – make special, thoughtful, personal sparkling wine. But in the U.S., it requires a bit of a treasure hunt to find one. We hope to persuade you that it is worth the hunt.

(Photo: Marcello Lunelli, winemaker and a third-generation owner of Ferrari Trento)

Trentodoc wines are not Prosecco, the easy-drinking, generally inexpensive Italian bubbly that nearly everyone loves. It is also not Champagne, though it is made the same way, known as Metodo Classico in Italy, and largely with the same grapes. Only Champagne is Champagne and Trentodoc’s taste profile is different.

But that taste profile – ah, it’s really something. And it’s the culmination of the vision of a man named Giulio Ferrari (no relation to the car maker), who decided in 1902 that this part of the Alps would be a great place for a sparkling wine that could compete with Champagne.

After studying in Champagne, Ferrari brought cuttings of Chardonnay into Italy—the winery says it was the country’s first Chardonnay--and made the wine in the same time-consuming way as Champagne. That means the second fermentation, which produces bubbles, occurs in the bottle, and with the wines receiving extended aging on their lees, the spent yeast cells. Ferrari’s wines became famous. By 1952, he was making 10,000 bottles a year. Because he had no heirs, he sold the winery to a local wine merchant and friend named Bruno Lunelli, Marcello’s grandfather, who had five children. The third generation runs the company now. Bruno Lunelli and other producers later also utilized Pinot Nero, or Pinot Noir.

In 1993, the region became a regulated area, or DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata). With that classification, the second in the world exclusively for bubblies after Champagne, came strict rules governing the wines’ production. (There’s a very good web site where you can read all the details.) Almost all are made with Chardonnay and-or Pinot Noir. Pinot Meunier, the other grape of Champagne, is also allowed, as is Pinot Blanc, but those two are rarely used.

(Photo: Trentodocs in the Palazzo Roccabruna's Wine Promotion Board of Trentino)

So, all in all, the entire region produces maybe 750,000 cases a year, which wouldn’t even put it within the top 25 wineries in the U.S. Ferrari, which makes more than 400,000 cases, and Rotari, which makes more than 200,000, are by far the biggest players, followed far behind by Altemasi (part of the Cavit empire) and Cesarini Sforza.

Because of the small production, these wines are made with careful attention to detail. They are wines with a purpose, and they taste like they are. It’s easy to explain how they are different from most Prosecco. They are, as a group, much more challenging, more focused, dryer, more acidic, better with food.

It’s more difficult to explain how Trentodoc wines are different from Champagne. During our visit, on a press trip sponsored by the Trentodoc producers’ association, we tasted dozens of Trentodoc wines. They have the same kind of acidity and lovely bubbles as Champagne. But they are fuller than Champagne, more mouth-filling. There are more floral notes than with many Champagnes, with very ripe fruits, especially apples, lemons, apricots and tangerines. They are fresh, intense, elegant and satisfying. And there’s another thing: Because of the soil and altitude, one of Trentodoc’s markers is a touch of saltiness. You really have to think about it, but, when you do, it’s there and it adds an extra layer of complexity that makes the wine not only delicious but fascinating.

The wines tend to be very dry. In fact, winemakers told us that the amount of dosage – the amount of sugary stuff they add when the wine is disgorged before it’s released – has decreased over the years as consumer tastes have changed. We were also pleased how many zero-dosage wines we saw. We’ve written that this is a worldwide trend we’re happy about because, too often, dosage can hide faults and we like our bubbly naked sometimes, confident to strut its unadorned self.

(Photo: John with Sommelier Roberto Anesi after his masterclass on Trentodoc wines)

Another thing: Quite a few of these wines are aged for a long, long time on their lees, which adds complexity over time. We tasted wines going back to 2004 and some that had been on their lees for seven years and longer and they still tasted fresh, lively and ready for aging at home. Champagne with that kind of lees aging can gain a kind of brioche-mushroom complexity that we enjoy; these, probably because of their awesome mountain acidity, showed little of that. Instead, the long aging softened the bubbles and the wine. That’s one more thing that doesn’t make Trentodoc wines better or worse than Champagne, just different.

We wish we could just say, hey, run on down to your wine store and get a bottle of Trentodoc! But, sadly, it’s not that simple. Making Trento DOC into Trentodoc might have created a nice name, but it’s not working all that well in the U.S. When we got back home, we looked at some websites to see which wines were available. Many of the best sites, including wine.com, reported “no results.” Hmmmm. So we kept trying to figure out a way to recommend finding them. In some cases, if we put in “Trento” we got hits, though this included other wines, including still ones, from the province. We also tried Trentino, but that gave us far too many wines to sort through, as did an advanced search with “Italian” and “sparkler.” But when used the wineries’ names, especially Ferrari, bingo!

So, with that in mind, let’s give you some names along with our tasting notes of a few wines that you might be able to find. The trade association also offered some distributors’ names. One general piece of advice: While the bigger producers make entry-level Brut wines that might cost $20 to $25 – and they are very good and excellent deals – we’d urge you, especially if this is your first Trentodoc experience, to move up just a bit to really get a fuller dose of Trentodoc intensity.

For instance, the entire Ferrari line, which is mostly all-Chardonnay, is good (Palm Bay International, New York). But we’d look for Ferrari Perle, made from selected lots of Chardonnay. It’s probably closer to $35 and worth more than that. It offers that combination of intensity and fullness – volume – that’s special. The Perle Nero is one of the few all-Pinot Noir Trentodoc wines and almost vibrates with a combination of fruit, minerality and muscularity. It is available in the U.S. for about $90, again worth more.

Rotari wines are widely distributed (Prestige Wine Imports, New York). Its rosé (75 percent Pinot Noir, 25 percent Chardonnay) is out there for around $20 and it’s lovely -- dry, fragrant and just slightly pink. We also particularly liked rosés from Altemasi (Palm Bay International) and Moser (Divino International Wine, Michigan), but they are harder to find.

The Altemasi Millesimato is a serious wine, with some real weight and amazing balance, a real winemaker’s wine. It’s available for $35 to $60 and, no, that makes no sense.

We don’t know why – since the winery only makes about 600 cases--but for some reason when we returned we found wines from Gaierhof at a couple of stores near our home. We hadn’t visited that winery or tasted its wines, but they were available for $14.99, which seemed like a safe bet, so we bought a few bottles. They were not as intense as the others, but were quite pleasant, with tastes of ripe apples and pie spices. We immediately thought of pork with apples and sauerkraut.

(Photo: Cesarini Sforza winery's savvy tableau, catnip for journalists)

And put this on your early holiday list for your wine-geek friend: Maso Martis Madame Martis, which is the only wine we tasted with a little bit of Pinot Meunier. It’s stunning, with layers and layers of flavor. We smelled and tasted rich citrus, some cinnamon, a bit of hay and – this is surprising – a slight touch of radish, a pleasant bitterness in the finish. The 2009 we tried rested on its lees for 110 months. It’s a wine to talk about all night. It costs about $108 and is available, for some reason, at the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. You never know. (Noble Harvest and Solstars Inc., both in New York; Elevation Wine Fund, Illinois.)

Sometimes wine isn’t easy – not to make, not to sell and even not to buy. Since Ferrari is so well-distributed, you might begin by asking your wine merchant for that because we’d bet other Trentodoc wines will be in the same general area of the store. Meantime, the Trentodoc institute might want to look into why most search engines don’t recognize “Trentodoc,” even when a store has the product, and try to do something about it. That might help the whole region including – yes – several passionate producers we met who make excellent wine and bemoaned their inability to break into the U.S. market.

One tip on serving: The wines’ complexity shows better with a bit of air and warmth. A few producers were aghast at this suggestion, because of the loss of some beautiful bubbles, but we might even decant the higher-end Trentodocs.

From what we can tell, many Americans have visited the Dolomites. Friends told us that this area, part of the Trentino-Alto Adige region that borders Switzerland and Austria, is one of the most beautiful places in the world and they were right. Trendodoc wines are not only delicious and unique, but a way to bring the Dolomites home, even if you’ve never been there. Just look at some pictures of those sheer mountains and imagine the commitment and love that must go into making that wine.

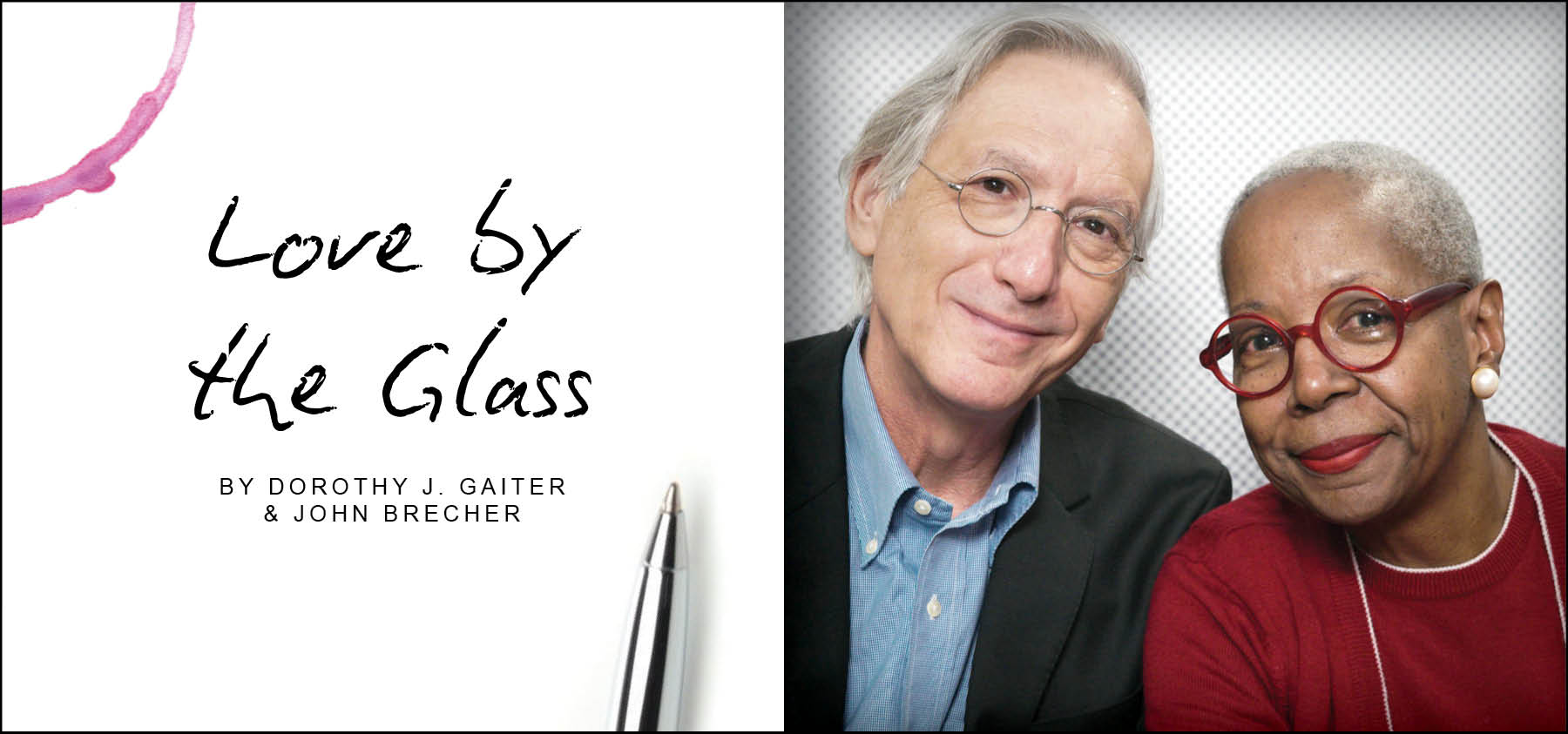

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective

Banner art by Piers Parlett