I. Origins

There is more than a little irony that Gernot and Heike Heinrich met in a beer garden. That was some 30 years ago, in Salzburg, Austria. Heike was from Germany, working in fashion and PR. Gernot had vineyards waiting for him back home, in Austria’s red wine haven of Burgenland. “My parents had a little estate,” he relates. “But they did not necessarily want me to go into wine.” Undeterred, he enrolled at Klosterneuburg, Austria’s preeminent enology school, to study wine technology. “I was born with a love of nature and wine, and I am drawn to creativity. But I don’t sing or paint, so wine is my welcome medium of expression.”

In 1989, when Gernot returned to his parents’ estate in the village of Gols, they had scarcely a hectare — “not big or important enough to survive on its own. That’s why Heike and I basically started our own estate parallel to that one, so we could be self-sufficient.” Since then, the growth of Weingut Heinrich has been as swift as it has been considered. At the time Gernot and Heike were married, in 1993, they were up to 2 hectares. Today, it’s 100 hectares, with production of close to half a million bottles a year — the entire estate farmed biodynamically or in conversion to biodynamics, certified by both Demeter and Respekt Biodyn, the wines made, in Gernot’s words, by “allowing them and ourselves the freedom of increasingly less intervention,” and above all with an acute sense of rhythm, place, and time.

“It’s been a steep climb,” he concedes, “but it’s simply been a matter of the right decisions at the right times. It’s been possible in part because many small hobby growers stopped working their vineyards — especially the steepest, most difficult ones — and sold them. We were able to buy them.” More broadly, the estate’s growth reflects the factors that have made Burgenland the beating heart of this sort of thinking, farming, work, and wine since the turn of the century.

II. Gols

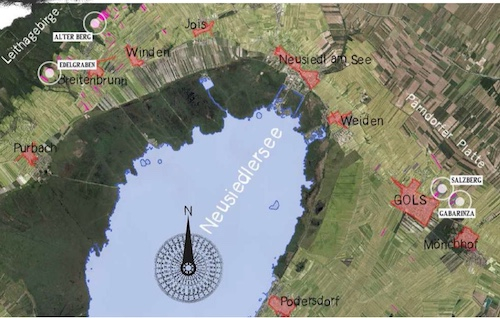

Gols sits just east of the Neusiedlersee, a vast but very shallow lake that has actually dried up entirely many times. (When that last happened, in 1866, local farmers assumed the lake's loss was their gain and started staking out the lake bed for plantings — only to have the lake fill up again.) Today, much of the area around Neusiedlersee is a designated national park, home to more than 300 species of birds and a rich variety of plant life all thriving in the mix of meadows, pastures, salt ponds, and fresh water surrounding it.

East of the lake, vineyards stretch flat toward the Hungarian border. Soils tend to be sandy loess and loam and the climate marked by the long sunshine hours, heat, and relative dryness of the Pannonian plain. All this favors red varieties, notably Zweigelt and Blaufränkisch. West of the lake, vineyards benefit from the cooling effects of the nearby Leithaberg mountain range. The low, forested peaks are the easternmost extension of the Alps, part of the so-called Kalkalpen, or limestone Alps. Soils are, accordingly, dominated by limestone as well as schist. They channel breezes from the north for cooler expressions of the red varieties and vibrance in an array of whites, which, for the Heinrichs, include Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Neuburger, Roter Traminer, Welschriesling, and Muscat Ottonel.

(Photo: Weingut Heinrich's sites, arrayed around the northern tip of Lake Neusiedl)

“We want to make connections between the eastern and western sides of the lake, especially in our entry-level wines. But we are also making more and more wines of specific origin, including single vineyards,” Gernot explains. “I believe it’s very important to make clear the close connection between a wine and where it comes from, as well as the corresponding characteristics of that place, to explain why a wine tastes the way it does.”

Since 2006, the Heinrichs have been betting on the future of the Leithaberg, where they have added more than 60 hectares of limestone- and schist-dominated vineyards in the villages of Winden and Breitenbrunn. The lower temperatures there “are very important for maintaining freshness in the wines, especially Blaufränkisch, a late-ripening variety, where the slow endphase-ripening is essential. We harvest the same varieties two weeks later in the western vineyards than the eastern,” Gernot notes. In response to climate change, the Heinrichs are also in the process of planning where to plant on more northern-exposed slopes — “for more acidity, more freshness.”

When they select a new site, the key criteria, beyond altitude and exposure, are soil type and vitality. Gernot notes that “in some cases we found vineyards that were very old and had been abandoned, so they were quite wild, which is very positive. It’s easier when you have that kind of biodiversity of plants and microorganisms.” If they find sites planted to the right vines, they preserve those — “but only,’ Gernot says, “when the variety and soil are a perfect fit for each other.” Over the past 15 to 20 years, they have replanted widely to loose-clustered, small-berried clones, particularly of the Austrian native Blaufränkisch, which now comprises roughly half their vines.

“What’s crucial is to preserve the vitality of the soils,” Gernot states. “Only when you have microorganisms in the soil and on the plant do you achieve the balance necessary to give the plant more resistance, more resilience — against all diseases, including fungal diseases. This is the aim of a holistic approach to caring for the vines. That’s why we also have sheep, geese, and horses — so we can strengthen the fertility of the soils. As is common in biodynamics, we try to do this through a homeopathic approach, through the preps, compost, teas, and plant extracts, to stimulate certain metabolic processes in the vines.”

Heike points out: “The problems we have to contend with now are the same as almost everywhere in the world: heat and drought. Compost helps us to counter this. In total, we make between 1,000 and 2,000 tons a year, using all the organic waste we generate on the farm.” Gernot agrees: “It is very, very important to build up the soils and increase the proportion of hummus in them, to trap moisture, and offer many more habitats for all microorganisms, and of course capture more CO2. Your carbon footprint is markedly smaller when you can consistently trap CO2 in the topsoils. In the end, the secret to making a living wine is that the wine brings the living soils into the bottle. It’s often said that wine is the capillarity of the soil — and that is precisely what we should feel in the wine. In the end, only the microorganisms can make nutrients available to the plants. You can only make a terroir-influenced wine if the soil is alive. If the soil is dead, you can’t sense the terroir.”

III. Biodynamics

Few other places in the world have made themselves as synonymous with the biodynamic ideas behind these practices as Gols has. This is largely thanks to the catalytic work and critical mass of Pannobile, a group of likeminded producers from the area, among them the Heinrichs, as well as Claus Preisinger, Paul Achs, Judith Beck, Andreas Gsellmann, Hans and Anita Nittnaus, and Helmuth Renner (father of the Rennersistas). “The original reason for founding Pannobile,” Gernot explains, “was the wish to wake the region from its ‘Sleeping Beauty’ rest and to show the world how good the wines here are. As a group we could achieve more than as individuals.” He cites “a very lively exchange of experiences” as the key to Pannobile's success. “In 2006, we all began to work biodynamically. We cooperated to make the preparations, share machinery, learn how to use the prep sprayers, and so on.”

Few other places in the world have made themselves as synonymous with the biodynamic ideas behind these practices as Gols has. This is largely thanks to the catalytic work and critical mass of Pannobile, a group of likeminded producers from the area, among them the Heinrichs, as well as Claus Preisinger, Paul Achs, Judith Beck, Andreas Gsellmann, Hans and Anita Nittnaus, and Helmuth Renner (father of the Rennersistas). “The original reason for founding Pannobile,” Gernot explains, “was the wish to wake the region from its ‘Sleeping Beauty’ rest and to show the world how good the wines here are. As a group we could achieve more than as individuals.” He cites “a very lively exchange of experiences” as the key to Pannobile's success. “In 2006, we all began to work biodynamically. We cooperated to make the preparations, share machinery, learn how to use the prep sprayers, and so on.”

(Photo: Gernot Heinrich enriching vineyard soils with biodynamic compost)

The Heinrichs’ path to biodynamics began with a serious study of the works of esoteric Austrian philosopher and late-life agricultural reformer Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), whose 1924 Lectures on Agriculture are the basis for what we consider biodynamic viticulture today. “In the beginning,” says Gernot, “we read Steiner together, like the Bible — both his lectures and his other philosophical works. I believe Steiner’s very deliberate intention was not to create a set of rules that everyone would follow, but to help free farmers to think and decide for themselves. What is paramount for us is observation and individual interpretation. Everyone is meant to find his or her own biodynamic way.”

Heike adds a parenting comparison, apt for a thoughtful mother of three: “It’s just like when you have children. You don’t sit down and say, ‘This one book will teach me all I need to know.’ Rather, you have your brain, your heart, your instincts, your intuition, your role models. It’s the same with viticulture.”

(Photo: Gernot and Heike with some key vineyard workers)

“Of course there were many things Steiner simply couldn’t have known at the time he was writing,” Gernot continues. “We are now a step further. One of the basic principles of Steiner’s thinking is that plant development can be stimulated homeopathically, using the finest, most minute quantities of materials, and that human beings are the basis for this. The sun, moon, and stars have an enormous influence on human beings and on the entire planet. All of these elements must be included.” Heike notes that when she encounters skeptics, she reminds them of the tides — “the best way to make clear how much influence the moon, for example, has.”

At their current size, one challenge for the Heinrichs is staying close to the rhythms of nature. “It certainly benefits us that a large part of our holdings are in the immediate vicinity of our winery, where we can walk the vine rows every day,” Gernot points out. “Moreover, we have a terrific team, some of whom started their biodynamic training with us back in 2006. That means many eyes (and hearts!) that can observe. We can’t always take every step in exact accordance with the lunar cycles, but with an appropriate number of coworkers, we come very close. And working biodynamically also encompasses a social consciousness, with human beings at the heart of things no matter how much land stands behind them.”

Biodynamic farming mandates “very exact, very detailed work with the vine canopy, the fruit zone to ensure the grapes are well ventilated and that no botrytis or other fungal diseases — powdery mildew, downy mildew — can develop,” Gernot explains. “It’s really important that this work be done correctly. Beyond this, we can support the vines’ resistance through biodynamic preparations and, in part, copper applications. In general we try to use very little copper, but in certain cases, in damp years, it’s essential for fighting downy mildew.”

Biodynamic farming mandates “very exact, very detailed work with the vine canopy, the fruit zone to ensure the grapes are well ventilated and that no botrytis or other fungal diseases — powdery mildew, downy mildew — can develop,” Gernot explains. “It’s really important that this work be done correctly. Beyond this, we can support the vines’ resistance through biodynamic preparations and, in part, copper applications. In general we try to use very little copper, but in certain cases, in damp years, it’s essential for fighting downy mildew.”

(Photo: Living soils, living wine)

Disease pressure is a serious consideration in the area around the Lake Neusiedl. In fact, the region’s reputation was made by the noble rot-affected grapes that yield its extraordinary dessert wines. How then do growers like the Heinrichs, who focus almost exclusively on dry wines and have only nature’s toolkit to combat disease pressures, keep their grapes healthy? “First of all,” Gerhard clarifies, “the sweet wines come more from the Seewinkel area, further south along the eastern side of the lake. We are farther north, where there is a greater influence from the cooler, western winds. On the other side, the vineyards are higher, up to 350 meters above sea level, and there it’s also markedly drier.”

Manual harvest and sorting are essential. “It’s easy to sort white varieties, for the reds you have to look a little more carefully. Especially for red wine and the macerated whites, there can be no botrytis, the grapes have to be absolutely clean,” Gernot explains.

IV. Cellar

The Heinrichs make their wines just as they grow them: hand in hand with nature, relying on gravity flow, natural yeasts, ambient ferments, little to no SO2, with aging in wood and, increasingly, clay vessels, and above all an acute sense of rhythm, season, and time. “A throughline of all our wines is that they are totally dry and they all have this saltiness from the limestone soils,” explains Gernot. “And it’s particularly important to me that this is expressed because it cleanses the palate and brings freshness.”

As they have moved from the elegant traditional winemaking style they started with something more avant garde, Gernot and Heike have sought ways to bring their customers along. Their “Naked” project is emblematic of this. “It started with vintage ‘17. We wanted to create a wine that could lead consumers on a path to natural wine. Not to make it too complicated, not with too extreme skin contact. It’s a cuvee of almost all the white varieties we have, mostly Chard, Weissburgunder, but also Welschriesling, Neuburger, Gruener Veltliner, Muskat Ottonel, which you can smell right away. The Muskat is skin fermented in amphora; the remainder is whole cluster, lightly pressed and then fermented in large cask. Zero SO2 added. Very fine tannins, just slightly perceptible, to support the wine and give it structure and liveliness, but never too dominant.”

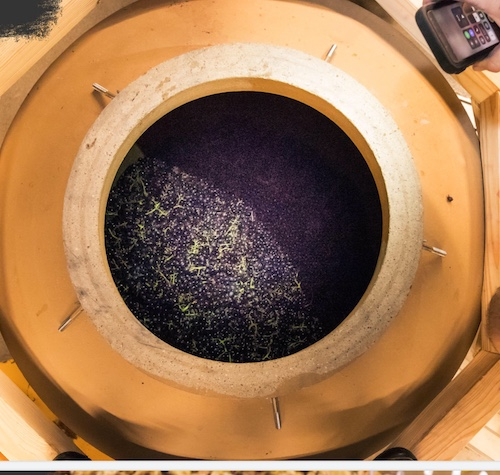

(Photo: A serious commitment to amphora)

Over the past five years, they have taken a further step from convention, embracing amphora aging and skin ferments as a way of gaining structure and articulacy in the wines. “It’s simply brilliant to work with amphora,” Gernot effuses. “As small vessels with large inner surface areas that are porous to a degree, they are perfectly suited to an elegant wine style.” He is convinced they are ideally suited to skin-macerated whites, “but also more and more for the reds, especially Blaufränkisch, because we believe the amphora give less wood and less oxygen influence, so the wines mature very, very slowly. This is exactly what we want: a very slow development that leaves a wine that is fruit dominant and elegant.” As evidence of their commitment to the style, the Heinrichs will soon increase the total number of amphora in their cellar to 140.

Over the past five years, they have taken a further step from convention, embracing amphora aging and skin ferments as a way of gaining structure and articulacy in the wines. “It’s simply brilliant to work with amphora,” Gernot effuses. “As small vessels with large inner surface areas that are porous to a degree, they are perfectly suited to an elegant wine style.” He is convinced they are ideally suited to skin-macerated whites, “but also more and more for the reds, especially Blaufränkisch, because we believe the amphora give less wood and less oxygen influence, so the wines mature very, very slowly. This is exactly what we want: a very slow development that leaves a wine that is fruit dominant and elegant.” As evidence of their commitment to the style, the Heinrichs will soon increase the total number of amphora in their cellar to 140.

V. Freyheit

In 2011, the Heinrichs introduced their Freyheit wines, easily recognized by sturdy earthenware bottles and the amber liquids inside them. “We wanted to have the wines we ferment in the earthenware amphorae in earthenware bottles because its helps to convey how the wines were made and we think the wine is better protected,” Gernot explains. “The name comes from Steiner — Philosophy of Freedom [“Freyheit” in an antiquated spelling] is one of his defining works, but Goethe also wrote a great deal about freedom. These wines came about when we decided we wanted to make a macerated Traminer to capture all the aromatic variety in the skins. Then we saw that this wine could work without any added SO2. Without it, the wine had more flavor, more liveliness. We are making more and more macerated white wines, especially from the aromatic varieties, such as Traminer, Muskat. I find that Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, and Chardonnay lend themselves very, very well to maceration because the aromas are localized in the skins and we get more structure and freshness from this approach.”

The 2016 Graue Freyheit, for example, is a cuvee of Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris and Chardonnay that spent three weeks on the skins, was raised in amphora with additional aging in large wood casks on the full lees, bottled unfiltered and cloudy. Orange wine authority Simon Woolf has written of this wine: “This is natural winemaking with laserlike precision and care, nothing lazy, clumsy, or dirty. The fruit feels juicy and expressive, the tannins are understated but important for their nutty, savoury backbone. For anyone whose idea of orange wine is something brutal, tannic and rustic, this might just be a revelation — it’s seductive, balanced and all too easy to empty the bottle.” Indeed, the spiky texture and earthy-citric notes of kumquat, orange, and forest floor are exactly what make amber wines of this quality so alluring.

VI. Tradition

Their classic line of reds, the Heinrich hallmark, is equally compelling. Blaufränkisch, whether from single sites or on the regional level, is charged with penetrating minerality, peppery and savory, with extremely fine tannins and notes of forest bramble. A 2013 St. Laurent tasted with them was the best example of the variety I’ve encountered, more northern Rhone Syrah than anything else, with alluring notes of game, black olives, and licorice on a filigree frame. “The grapes for this wine,” Gernot explains, “come from the Leithaberg, from Breitenbrunn and from Gols. On the one side are more slate soils and on the other, red gravel. St. Laurent doesn’t work on loamy soils. Sand works, but especially gravel. There’s always an element of leather and game in St Laurent and the tannins to age a good five to seven years still.”

Their classic line of reds, the Heinrich hallmark, is equally compelling. Blaufränkisch, whether from single sites or on the regional level, is charged with penetrating minerality, peppery and savory, with extremely fine tannins and notes of forest bramble. A 2013 St. Laurent tasted with them was the best example of the variety I’ve encountered, more northern Rhone Syrah than anything else, with alluring notes of game, black olives, and licorice on a filigree frame. “The grapes for this wine,” Gernot explains, “come from the Leithaberg, from Breitenbrunn and from Gols. On the one side are more slate soils and on the other, red gravel. St. Laurent doesn’t work on loamy soils. Sand works, but especially gravel. There’s always an element of leather and game in St Laurent and the tannins to age a good five to seven years still.”

(Photo: Shell limestone in the Leithaberg)

VII. Future

“We want to continue on the path we have embarked on,” Gernot says. “The greatest challenge will be to establish our new style in the market, as the taste for the flavor components in our wines — acidic, bitter, salty — has been lost or become undesirable. The biggest surprise of my career has been the resistance when we started some years ago with converting to biodynamics and changing the style of our wine. I didn’t expect so few people to understand this. Our customers did not like this kind of purity, this kind of saltiness in the wines. We had to change our customers, our partners.” Heike adds, “People thought biodynamic means bad. It’s still in people’s minds that since we converted to biodynamics the wine tastes different. We realize that doing less gives much more taste in the end. This is what motivates us, and what interests us and what helps us develop further. There is an excitement in finding an almost artistic form of expression, it’s a way of personally conveying this sensibility through the wine. That is the nicest aspect of the job. And that is what biodynamics allows us to express much more clearly.”

“I think the pendulum sometimes has to swing very far in the opposite direction in order to change things in society, to go to the extreme to create awareness and space for development,” Gernot reflects. “I think we have made advances in that we now have wines on the market without SO2, white wines with tannins, that find acceptance. Five or six years ago, it was very difficult to get out of this niche. But I have the impression that the understanding, the market for these wines has increased. It’s easier in the urban markets. In Austria, that’s also starting in Vienna, though not yet in Salzburg, for instance. It’s all about understanding and awareness, including awareness of the environment. Burgenland is an important force in building this awareness, along with other hot spots like Southern Styria, where they have the “Schmecke das Leben” group, with Tscheppe and Strohmeier, who started with this very early on. We’ve laid the cornerstone with the planting of the vineyards in the top sites in Gols and in the Leithaberg. What comes after that, the next generation will decide.”

All images courtesy of Weingut Heinrich.

This interview was conducted in New York in German and translated by the author.