111 Wines from Austria You Need to Drink is a fresh-off-the-press, bottle-by-bottle guide to one of Europe’s tiniest, most compelling wine countries. The book is only available in German, but even if you only label gaze, you’ll find it’s an engaging and reliable road map to this compact empire of wine. The authors winnowed Austria’s 4,000 commercial producers to a relative handful and their number one pick may take some by surprise: Domäne Wachau’s Ried Achleiten Riesling Smaragd (2017). Yes, it’s an excellent expression of Austrian Riesling’s capacity for virtuosic terroir expression, impressive longevity, opulence without excess, all at an affordable price. But from a country abounding in storied small family producers, what really stands out is that this honor went to … a co-op. A closer look reveals why.

1. At the heart of Austrian wine. The Wachau is one of the world’s most stunning, historic wine regions. Though less than an hour by car from Austria’s stately capital city, Vienna, it feels like a long-lost piece of Mitteleuropa. Its recognition as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site rests as much on its Baroque architecture as on an extraordinary number of tiny, mostly terraced vineyards, where small grower-producers with world-class reputations have been making wine for centuries. Many believe Grüner Veltliner and Riesling find their Austrian apogee here on the sheer, stony banks of the Danube.

2. Big size, small focus. Domäne Wachau is large. Very large. With 250 growers, 440 hectares, and 3,500 individual sites, it accounts for a full third of the Wachau’s total vineyard area.  Its focus is two-fold: the world-class collection of holdings in exceptional single-vineyard sites and classic regional expressions. “Precise definition and clear expression” of the Wachau’s chiseled terroir are what Domäne Wachau’s winemaker, the knowledgeable, no-nonsense Heinz Frischengruber, says are the keys. The entire region is quite compact — only 33 km (20 miles) end to end — and minor differences in aspect, elevation, and river proximity have a major impact on growing conditions in the hot, dry summers here. “In a span of 15 km [9 miles], between the wine towns of Spitz and Durnstein,” the latter being home to the coop’s cellars, “you can get 10-14 days difference in ripeness,” Frischengruber says. This scope and variation give him a nuanced palette with which to paint, as it were, wines of exceptional balance and harmony.

Its focus is two-fold: the world-class collection of holdings in exceptional single-vineyard sites and classic regional expressions. “Precise definition and clear expression” of the Wachau’s chiseled terroir are what Domäne Wachau’s winemaker, the knowledgeable, no-nonsense Heinz Frischengruber, says are the keys. The entire region is quite compact — only 33 km (20 miles) end to end — and minor differences in aspect, elevation, and river proximity have a major impact on growing conditions in the hot, dry summers here. “In a span of 15 km [9 miles], between the wine towns of Spitz and Durnstein,” the latter being home to the coop’s cellars, “you can get 10-14 days difference in ripeness,” Frischengruber says. This scope and variation give him a nuanced palette with which to paint, as it were, wines of exceptional balance and harmony.

3. Profound history. For centuries, the church played a vital role in developing the wine culture of the Wachau. Monks brought rigor and recordkeeping, gaining a meticulous understanding of the interplay of soils, microclimates, and varieties over the centuries. By 1790, secularization had swept the vineyards into the hands of private landowners. Over time, these holdings were fragmented, leaving myriad growers with tiny parcels. In the 1930s, a handful of these owners, with plots of 1 to 5 hectares each, joined together to form the coop that is today Domäne Wachau. As recently as the ‘50s, the Wachau was still more renowned for its orchards than its vines. But when fruit prices dropped around that time, growers had fresh incentive to recultivate the old vineyards, propelling the wines to greater attention. Many of the sites now in the Domäne Wachau fold are graced with plantings from around this time; the old vines, with their deep roots, soil symbiosis, and smaller berries, translate into even more articulate expressions of place.

4. Strong leaders, deep roots. It takes two experienced, charismatic figures to corral so many pieces and personalities into a stable of consistently fine wines.  Managing Director Roman Horvath, a Master of Wine, and Frischengruber, a Wachau native with enology degrees from Austria’s Klosterneuburg and Germany’s Geisenheim, have led the coop since 2004. Frischengruber says the secret to their long-term success is “trust in the experience of our growers and a focus on preserving the unique terroir character of the wines.” He himself is the fifth generation of a Wachau winemaking family. “You have to know your vines, your terroir and to do that, you have to stay in one place for a long time. I love Burgundy — Cote d’Or, Chablis — but I’d have to live to be 200 to understand them.” He and Horvath have deepened their connection with growers by committing to regular on-site visits, understanding their concerns and offering seminars and farming guidance. This investment in strong relationships with and among local individuals, families, and villages is what Frischengruber believes sets Domäne Wachau apart.

Managing Director Roman Horvath, a Master of Wine, and Frischengruber, a Wachau native with enology degrees from Austria’s Klosterneuburg and Germany’s Geisenheim, have led the coop since 2004. Frischengruber says the secret to their long-term success is “trust in the experience of our growers and a focus on preserving the unique terroir character of the wines.” He himself is the fifth generation of a Wachau winemaking family. “You have to know your vines, your terroir and to do that, you have to stay in one place for a long time. I love Burgundy — Cote d’Or, Chablis — but I’d have to live to be 200 to understand them.” He and Horvath have deepened their connection with growers by committing to regular on-site visits, understanding their concerns and offering seminars and farming guidance. This investment in strong relationships with and among local individuals, families, and villages is what Frischengruber believes sets Domäne Wachau apart.

5. Treating growers right. “Our grower/vintner families have been working on their small parcels for generations. They are extremely bonded with the land, the vineyards, the hillsides. We do not work with temporary employees or pickers from outside [the region]. It is always the family who works the vineyard, following our parameters. There is very little mechanization, it is a mostly handcrafted approach on the steep terraced vineyards. That makes the bond even stronger,” says Frischengruber, referencing the Wachau’s extensive drywall stone terraces, the oldest of which date to the 10th century. Maintaining these ancient features, let alone farming them, is costly and laborious. The man hours required to tend the terrace sites are five to six times higher than flatland vineyards. Frischengruber sees it this way: “The Wachau region offers the best ‘hardware’ with its great terroir. But the ‘software’ — the people, their passion for the work with nature in the vineyard, their wine growing skills — is so crucial.” Ensuring growers a fair price for the quality they achieve is essential element to Domäne Wachau’s success. “What was supposedly a disadvantage in the past we see today as a great asset: Small ownership, highly fragmented vineyards, small-scale structure,” Frischengruber notes. But when asked whether this model can be further expanded, he shakes his head: “Membership is full.” With a hint of a smile, he adds, “We already have the most interesting vineyards.”

6. True grand crus. Unusually for a coop, Domäne Wachau has holdings in some of Austria’s most revered vineyards. Among the region’s more than 120 named sites, or Rieden, Achleiten stands out as one of Austria’s true grand crus. Wines from this vineyard, which takes its name from Echleiten, “a slope with oak trees,” were already well known in the 12th century. Domäne Wachau has a generous 8.5 hectare cut. At the upper reaches, primary rock soils are of porous, friable gneiss, well suited to Riesling. Closer to the river, metamorphic clays and shales that weather into thin, sandy, quick-draining soils, are favored by Grüner Veltliner. The vineyard is famed for giving structured, long-lived wines with a smoky, mineral note, one that the authors of 111 Wines aptly describe as “suggestive of a hearth gone cold.”

7. Of grass and lizards. In the 1980s, a group of Wachau producers formed an organization that sought to highlight and protect the singularity of the region’s wines. This group categorized the dry white wines produced by their members into three levels, based on alcohol percentages in the wines. There is the light Steinfeder, named for a vineyard grass and typically consumed young and fresh in Austria (making it unlikely to be found in export markets). Bantamweight Federspiel, which takes its name from a falcon common to the Wachau, brings moderate body and zest. Powerful, fulsome Smaragd, named for the sun-loving emerald lizards often seen basking on the Wachau’s terrace walls, must be above 12.5% alcohol and are specially built for years if not decades of maturing.

8. Growing towards organic. As these names suggest, the Wachau is a habitat for a range of singular flora and fauna. To preserve this delicate ecosystem, the entire region is farmed without insecticides. Instead, growers rely on pheromones to “sexually confuse” pests, a method now common in many wine regions. Organic farming is a challenge Domäne Wachau has yet to tackle head on. Only a tenth of co-op members have committed themselves to the practice. Frischengruber says: “I don’t like to tell people they have to do things just one way.” But he is encouraging growers to enhance vineyard biodiversity where they can, for example by “working with a specially mixed cover crop that helps to maintain a diverse biological system in the vineyards.”

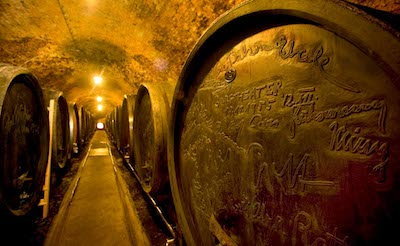

9. Cellar style. Domäne Wachau’s philosophy of handling all wines fairly similarly across the board — protective juice handling with temperature-controlled fermentations, long lees aging, and late SO2 additions — is an important factor in controlling costs and allowing the vines to speak. Frischengruber waves away his own influence, “I make no big difference; harvest time and terroir make the differences. People work so hard in the vineyards, I don’t want to do anything in the cellar to change what they have produced.”

9. Cellar style. Domäne Wachau’s philosophy of handling all wines fairly similarly across the board — protective juice handling with temperature-controlled fermentations, long lees aging, and late SO2 additions — is an important factor in controlling costs and allowing the vines to speak. Frischengruber waves away his own influence, “I make no big difference; harvest time and terroir make the differences. People work so hard in the vineyards, I don’t want to do anything in the cellar to change what they have produced.”

10. Exceptional value. Because of this, Domäne Wachau offers one of the best ways to affordably drink through some of Austria's most iconic terroirs for Riesling and Grüner Veltliner.

Now, about that "Nr. 1" wine? Frischengruber says that though the Ried Achleiten Rieslings are built to age, they “always offer a great mouthfeel, firm mid-palate but also stunning finesse and great tension on the palate.” When I tasted the 2016 recently with Frischengruber in New York, the wine was already revealing succulent peach and apricot flavors, broadened by extract and evident lees aging, yet with any tendency to fleshiness kept firmly in line by a tensile acidity. The suggestion of flint added depth and allure. Two other reference point wines to look for are the Grüner Veltliner Federspiel Ried Liebenberg (2018), a bottle of dancing purity and vivacity with classic white pepper and herbaceous notes and the arresting Riesling Federspiel Ried Bruck (2018) — lively, citric, and lithe. All are drinking gorgeously now and likely for years to come.