Pinotage, made from the only grape created in South Africa, is one of the few wines we know that people either really like or really hate. Maybe Retsina is another.

In 2014, Dottie wrote about a delicious Pinotage from L’Avenir in the Western Cape and began her column this way: “I want to talk to you about Pinotage. Hello? Hello? Still there?”

Yep, it’s that kind of wine.

In general, we think any grape, when planted in the right place and handled respectfully in the vineyard and in the winery, can produce enjoyable wine, sometimes in many styles. Enjoyable, to us, doesn’t mean that it necessarily tastes wonderful, but it must hold our interest, maybe require us to stretch a bit.

We had two Pinotages recently that did those things and more -- they were special and authentic -- and with cool weather upon us, this is a wine that goes well with roasts of all kinds: meat, fish and vegetable. And the prices were attractive, too. The wine we especially liked, 2017 Lievland Vineyards Bush Vine Pinotage, tasted true to its type, spicy, rich, blueberries and blackberries, with nice acidity and none of the burnt-rubber, acetone qualities that can be off-putting in Pinotage. With a price around $15, it could be our new house red.

The second, 2017 M.A.N. Family Wines Bosstok Pinotage, about $10, from the same team, was pitched, we think, to folks who prefer a more modern or international-style Pinotage. Importer Vineyard Brands sent us these two to sample.

The second, 2017 M.A.N. Family Wines Bosstok Pinotage, about $10, from the same team, was pitched, we think, to folks who prefer a more modern or international-style Pinotage. Importer Vineyard Brands sent us these two to sample.

(Photo from left to right: José and Marie Condé; Tyrrel and Anette Myburgh; and Philip and Nicky Myburgh of M.A.N. Family Wines)

Now about that grape. While there seems general consensus that Chenin Blanc is South Africa’s signature white grape variety — we remember when it was called Steen — some wine experts demur that Pinotage, called South Africa’s “first and only” cultivar, should not be considered the country’s signature red grape.

“Pinotage is a uniquely South African grape, but not the country’s signature. Inasmuch as South Africa has one, I would say it is Chenin Blanc,” Jim Clarke, marketing manager of Wines of South Africa USA, wrote us in an email. Chenin Blanc, he noted, is the country’s most-planted grape, “with more in South Africa than in the rest of the world combined.”

Well, yes, but what about its best-known red grape, Pinotage?

“It was pushed as a signature in the 1990s and early 2000s, for good reasons. In 1991, at the very moment embargoes were falling and the South African wine industry was rejoining the rest of the wine world, Kanonkop’s 1989 Pinotage won the Robert Mondavi Award for best red wine in the world at the International Wine Competition,” Clarke said. “So just as South Africa was reentering the world wine market, that market said Pinotage was the best. But a lot of them were not up to snuff, and it got a very bad reputation with the trade. I can go into the technical details if you want, but basically it’s the combination of high malic acid, high pH, and very high nutrients that make for a very fast fermentation if not controlled.”

Consider what Nina Caplan wrote in 2014 in her “dispatch from the Pinotage wars” in New Statesman America, an offshoot of the august London-based cultural and political magazine that George Bernard Shaw helped found: “I just feel that Pinotage suffers as much from a design error as the dodo did and should follow it into extinction.”

So how was it designed?

Next year will be the 95th anniversary of its creation by Abraham Izak Perold, the first professor of viticulture at Stellenbosch University. Perold was attempting to create a grape that would make famously difficult-to-grow Pinot Noir heartier. So he crossed Pinot Noir with Cinsault, a rugged southern Rhône variety, known then in South Africa as Hermitage. Perold’s experiment produced only four seeds that he planted in 1925 in his garden on campus, not in the university’s experimental farm. When he departed for another job, he left his experiment in his back yard which, depending on your view, was fortunately or unfortunately rescued by Charles Niehaus, a lecturer at the school who moved the young vines to nearby Elsenburg Agricultural College. There, another viticultural professor, C.J. Theron, grafted them onto a new type of rootstock. Perold and Theron together named the grape Pinotage. The first wine from it was made in 1941, the same year Perold died.

We asked José Condé, general manager of M.A.N. and Lievland wineries, if Pinotage is a hard sell. M.A.N. is a partnership of Condé and two brothers, Tyrrel and Philip Myburgh, fifth-generation stewards of Joostenberg, a multifaceted business that includes farming, an organic winery, a pork specialist butchery, a florist and dining spots, among other things. The initials of the trio’s wives’ first names spell MAN.

We asked José Condé, general manager of M.A.N. and Lievland wineries, if Pinotage is a hard sell. M.A.N. is a partnership of Condé and two brothers, Tyrrel and Philip Myburgh, fifth-generation stewards of Joostenberg, a multifaceted business that includes farming, an organic winery, a pork specialist butchery, a florist and dining spots, among other things. The initials of the trio’s wives’ first names spell MAN.

(Photo: José Condé)

“Traveling around the world, we have seen a lot of curiosity around Pinotage. When well made, it is an extremely food-friendly crowd-pleasing wine,” Condé wrote us.

“People are often looking for something ‘representative’ of South Africa and Pinotage fits this. So, no, it is not a particularly hard sell. However, it is a niche variety, so we feel it works best to sell into accounts that will actively hand sell it and promote it or those accounts that do well with slightly geeky or unusual wines.”

Of the M.A.N. Pinotage that we thought was more international, Condé wrote: “When we first started out, the most popular style of Pinotage was actually sometimes referred to as a ‘Barossa-style,’ meaning Bigger-is-Better. Although we toyed around with this style at the beginning, Tyrrel and I started to question the suitability of the style. Since both parents (Pinot Noir and Cinsault) make lighter, more aromatic wines, why were we pushing the grapes so hard?

“Why not try to back off and make something with a bit more finesse? So we started to experiment with that — picking a bit earlier and minimizing extraction at the end of fermentation — and we found it worked really well and got a great consumer reaction.”

The M.A.N. Family Wines are made with fruit mostly sourced from 30 growers in the Agter-Paarl region, in the Western Cape, north of Stellenbosch. The growers are part of a co-op whose grapes are blended to make mostly bulk wines sold in supermarkets, Condé wrote us. He and the brothers made the growers partners in M.A.N. and now get first pick of the growers’ crops, a “consistent supply of excellent quality dry-farmed grapes,” he explained. All of the operations have been certified sustainable and as treating their employees responsibly, according to the rules of the Wine and Agriculture Ethical Trade Association. What started as a 600-case operation has grown to 175,000 cases sold in 25 countries.

In our notes, we wrote: “Pleasant and easy to like. Fresh and fruity. Just a touch of ‘blue,’” the word Dottie often uses to describe Pinotage. “A great deal.” Seventy-five percent of the wine is made in stainless steel to preserve the freshness, and 25% gets oak.

In 2017, Condé and Tyrrel Myburgh purchased Lievland Vineyards, an existing winery in the Simonsberg Mountain's “Golden Mile” of wine estates in the northern end of Stellenbosch. M.A.N. makes about 24,000 cases of Pinotage and Lievland about 3,000 cases, Condé wrote, with about 25% of each imported to the U.S. “We found that it pairs very well with some foods that are a challenge — strong soy-sauce-based dishes, for instance. It has a natural umami note that works well,” he said.

In 2017, Condé and Tyrrel Myburgh purchased Lievland Vineyards, an existing winery in the Simonsberg Mountain's “Golden Mile” of wine estates in the northern end of Stellenbosch. M.A.N. makes about 24,000 cases of Pinotage and Lievland about 3,000 cases, Condé wrote, with about 25% of each imported to the U.S. “We found that it pairs very well with some foods that are a challenge — strong soy-sauce-based dishes, for instance. It has a natural umami note that works well,” he said.

(Photo: Cellar Master Tyrrel Myburgh)

We wrote in our notes on the Lievland: “Perfectly balanced. Nice fruit, maybe a little shy at the start. Quite elegant. There is no rubber and it is close in body to a light-ish Pinot Noir but the taste is darker than many Pinots. Very dry, with some earth. A drink-now-and-enjoy wine rather than a wine to talk about.”

Which is exactly what the men envisioned with both wines, that they would be everyday pleasures. Both wines are made by Riaan Möller.

Condé and Clarke both said consumers are curious about Pinotage and like it when it’s poured for them. “While the trade takes issue with it, consumers are typically interested and enthusiastic,” Clarke told us. “When I do a trade event, the wines are viewed with suspicion; at consumer events, people come looking for it and are disappointed if I don’t have one.

“Because of the attitude in the trade, Pinotage in the U.S. makes a great bet. Producers making Pinotage these days believe in the grape; they’re not making it for marketing reasons. Importers who decide to bring one in choose one they really believe in, because they know it faces a headwind,” Clarke added. “The distributor and the retailer are making the same sort of commitment when they decide to sell a Pinotage.

“By the time it’s on the shelf, it’s the most heavily vetted wine in the shop.”

But then there’s this, about Lievland Vineyards:

“The first time we visited the farm, we were struck by two horses that had adopted a baby springbok. This touching scene inspired our label: Cupid, the god of love, riding a springbok, South Africa’s national animal,” Condé wrote on the winery’s website.

Aww, how sweet, we thought, until we read that he and Tyrrel suggest springbok pie as a pairing suggestion for their Pinotage! “C’mon, guys,” we wrote Condé, who responded, “Hahaha. You are the first to pick that up — it was our little joke! But this is Africa, it’s the ‘Circle of Life.’ Get over it!”

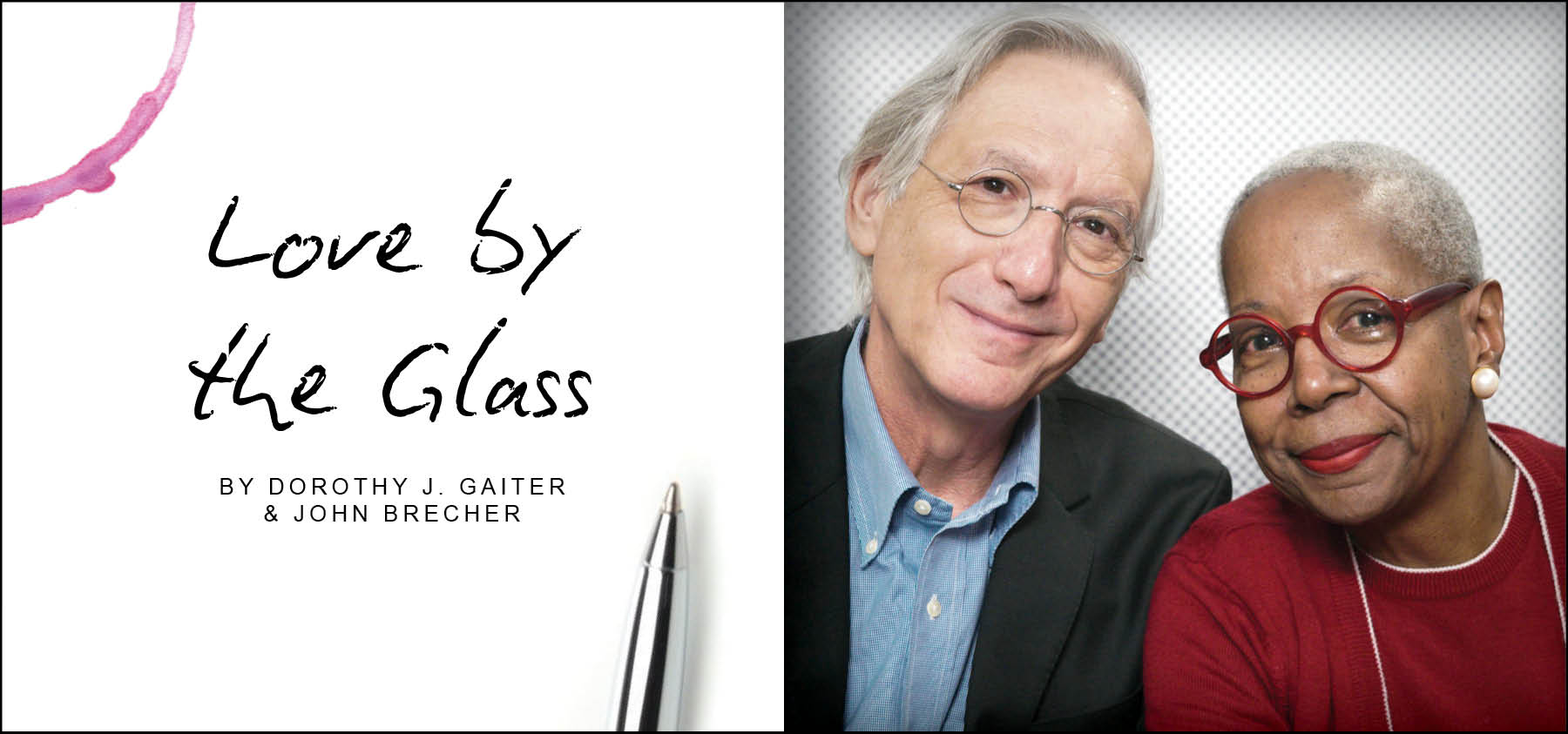

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective.

Banner by Piers Parlett