Surprise is one of many things that has kept us coming back to wine all these years, but even for us, this was unusual: Dottie was at the kitchen sink, with her back to John. He opened a bottle at the counter, maybe three feet away. As soon as he did, she stopped working and, without turning around, said, “My God. That nose is fabulous.” Then, after a few beats, she added: “Media’s back yard!”

After 46 years of tasting together, we speak wine in shorthand. When our first daughter, Media, was born, we lived in a Spanish-style house in Coral Gables, Fla., that had a yard filled with tropical fruit trees like mango, papaya and carambola, not to mention Key lime and grapefruit, pink and white. The fruity aroma of this wine was so distinctive and mouth-watering that it took us right back to that yard. It was like a cartoon that showed all sorts of fruits bursting from the neck of a bottle.

Unfortunately, we then got into a bit of a contretemps. It was over the S-word: sweetness. Dottie thought it had a little – not too much, but a touch. John thought it was dry but just intensely fruity. We had to know more about this wine.

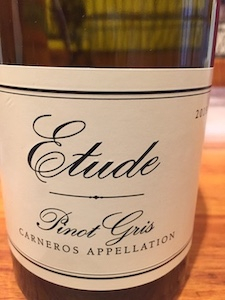

It was Etude Wines 2018 Pinot Gris from the winery’s cool-climate Grace Benoist Ranch Estate in Carneros that we’d received as a sample.

Etude always makes us smile because it reminds us of the late Rusty Staub. Rusty, as you certainly should know, was a classy player for the New York Mets (and other teams, including the Montreal Expos). He also loved food and wine. In the 1980s and early 1990s, he owned two restaurants in New York and we’d heard they had fine wine lists. As huge fans of both the Mets and wine (perhaps the latter soothes the pain of the former), we had to dine at one.

Tony Soter, a famous Napa Valley vintner, founded Etude in 1982 and it immediately became a much sought-after name for its Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon. But we’d never seen an Etude until 1990. There, on the list at Rusty Staub’s, was the Cabernet. (We struggled to get the label off and the vintage, unfortunately, was lost. However, we can see that 1,250 cases were made.) We were thrilled and we ordered it right away. It was delicious, with rich Napa Valley fruit and earth. As we were enjoying it, Rusty was making the rounds of his restaurant. The big man stopped, loomed over our table, looked at the wine, looked at us, smiled and then nodded. Talk about a home run!

For a long time, Pinot Gris was the only white Etude made, probably because it’s like a cousin to Pinot Noir, which Soter loves. Now Etude makes Chardonnay and a little bit of Pinot Blanc. When we were young, Pinot Gris, to us, pretty much meant Alsace, though it apparently hails from Burgundy. We loved Alsace Pinot Gris’ intense combination of acidity, spice and fruit flavors, earthiness, and fealty to its place of origin. Sadly, over the years, many supposedly dry Alsace Pinot Gris have gotten sweeter, obscuring the earthiness, minerality and natural acidity and making the wine ho-hum flabby, and also more difficult to pair with food.

Meanwhile, Pinot Gris has become a specialty of Oregon. While Pinot Gris and Pinot Grigio are genetically the same grape, wines labeled Pinot Gris often nod toward the Alsace style while the latter is associated more with the generally easy-drinking Italian style. We don’t often have a Pinot Gris from California that knocks our socks off; too many seem bland. So we’d guess they’re not wines a lot of people head to the store to pick up.

This one, which costs $30, should be an exception – and there’s a big-picture reason we’re really happy about that. In 2001, Soter announced he was selling Etude to giant Australia-based Beringer Blass, which ultimately became Treasury Wine Estates. He stayed on until 2007 as a consultant and now makes wine with his wife, Michelle, in Oregon at Soter Vineyards, specializing in Pinot Noir.

According to the company, Treasury is one of the world’s, and America’s, five biggest wine-producing companies, depending on how you count. It produces about 35 million cases of wine worldwide. Of that, just 50,000 cases are Etude.

Many wine writers, including us, bemoan the loss of family-owned wineries. Time and again, we’ve seen giant companies take over outstanding, unique wineries and turn them into something generic or worse. This Pinot Gris, with a total production of 3,640 cases distributed nationally, stands as evidence that it needn’t always be so.

That probably has a lot to do with Jon Priest, 57, who has been involved in the wine industry in California since 1986 and became winemaker at Etude in 2005, when Soter was still there. Priest is now senior winemaker and general manager. Etude is primarily a red producer and Priest told us “my passion is Pinot Noir,” but he added: “When we have something like our Pinot Gris, that’s pretty fun, too.”

That probably has a lot to do with Jon Priest, 57, who has been involved in the wine industry in California since 1986 and became winemaker at Etude in 2005, when Soter was still there. Priest is now senior winemaker and general manager. Etude is primarily a red producer and Priest told us “my passion is Pinot Noir,” but he added: “When we have something like our Pinot Gris, that’s pretty fun, too.”

“I often use the Pinot Gris as a wine to introduce our philosophy and approach toward winegrowing and winemaking, with minimal intervention in the winery,” he said. “Pinot Gris is a particularly good example of that. Those are exceptional vines grown in an exceptional vineyard and they really give us that wonderful depth of character. And in the winery I kind of back away. There isn’t a lot of winemaking, so to speak, in that wine.

“It starts with the vines and our vines are actually from Alsace, which was our inspiration for this early on. Site specificity is really important. The clones we grow are very low-yielding and have that concentration and depth. I think you can overcrop it like you can overcrop any grape, but you have to find the right balance and step away a little bit.

“You put this variety into oak and put it through malolactic and you basically obscure all of the charm and nuance that grape has. It’s a delicate grape. It can also be very acidic, it can be very tannic, so you have to treat it with kid gloves a little bit. That’s why taking a really soft approach to it in the winery is pretty important.”

He said he once worked at a winery that put its Pinot Gris through malolactic fermentation and clobbered it with oak and ended up with what he called an “insipid” wine. “I learned from that experience,” he added.

Etude’s Pinot Gris is Napa-Green grown in loamy soil, harvested at night to preserve freshness, gently pressed whole-cluster, fermented in small stainless steel tanks, then aged on its lees for five months before being bottled. The 2018 is 13.8 per cent alcohol, higher than we would have guessed, but well-balanced.

We were eager to hear Priest talk about his bosses at Treasury, which is not just huge but publicly owned. “Treasury Wine Estates has been exceptional at maintaining the integrity of some of their precious, smaller and even some of the larger, more well-established wineries in the portfolio…protecting that honesty and integrity,” he said. “It’s been good. My job is to help maintain that integrity and I feel very supported in that.”

OK, so about the sweetness. Not that it matters to us – of course! – but was Dottie right that it has a little residual sugar?

It turns out that the wine has 0.7 grams per liter of residual sugar, which would indeed be considered dry. (Here’s a nice chart and some good discussion of sweetness at Wine Folly. But some people can sense residual sugar down to 0.5, we’ve been told, and Dottie has always been more sensitive to it than John.

Sweetness isn’t necessarily a bad thing in wine by any means. Some of the world’s great wines are sweet and sometimes just a whisper of sweetness helps a wine come together. In any event, sweetness isn’t just a function of sugar. All sorts of things affect how sweet a wine tastes – the amount of balancing acidity is a big one, for instance, as is the amount of alcohol.

So Priest saved our marriage. He said we were both right.

“I love that there’s a spirited debate about this because if we can produce a wine that we classify as dry that comes across as having an impression of richness and sweetness from fruit but is not high in alcohol, so you’re not getting that glycerol from alcohol that can give a perception of sweetness, then that’s exactly what I’m after in this wine,” he said.

“I think that’s fantastic.”

Whew. Thanks, Jon.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective

Banner by Piers Parlett