This is a story about a grape and two men and how the three of them together changed the modern world of wine forever.

Both men were in Europe in 1955, but it would be more than a decade before they met. Warren Winiarski, a post-graduate academic and lecturer at the University of Chicago, was in Florence, studying the Renaissance statesman and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli. Nathan Fay, a California native who loved the outdoors, was climbing the Matterhorn, that massive range of mountains along the Swiss-Italian border so vast and forbidding it is known as the Mountain of Mountains. Fay, who had trained on lesser mountains, topped the Matterhorn in record time among the climbers on that day. According to Fay’s notebook in which he kept a diary of his preparations and the final Matterhorn climb, his guide won a handsome sum from fellow guides – they had bet that the “American” wouldn’t even summit.

Six years later, in 1961, Fay planted the first Cabernet Sauvignon vines in what would become the Stags Leap District of Napa Valley, a location widely believed to be too cold for that variety to thrive. That planting happened 60 years ago this year and, in an extended sense, the seeds of those vines still bear fruit all over the wine world.

Six years later, in 1961, Fay planted the first Cabernet Sauvignon vines in what would become the Stags Leap District of Napa Valley, a location widely believed to be too cold for that variety to thrive. That planting happened 60 years ago this year and, in an extended sense, the seeds of those vines still bear fruit all over the wine world.

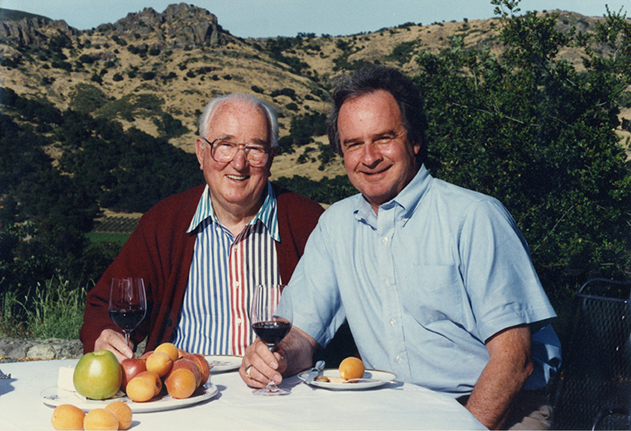

(Nathan Fay, left, and Warren Winiarski in 1986 above the vineyards.)

Meanwhile, Winiarski had an itch his academic life could no longer scratch. During his studies in Italy, he had fallen in love with a way of life in which wine was an everyday, civilized accompaniment to meals. As he puts it, “I was never the same after that.”

Eventually, he and his wife, Barbara, began to contemplate a complete upending of the life they’d known in Chicago, where their first two children were born and where Winiarski had been teaching at the University. They’d heard exciting things were under way in California involving winemaking. For more than half a century, California’s once vaunted and prosperous wine industry had lain dormant, wiped out by disease and then Prohibition. Finally, there were stirrings of a wine renaissance. The couple thought, “Why not pack up the kids and the books and head out to California to be a part of it?” Winiarski had zero winemaking experience. Nonetheless, with not much more in their pockets than their dreams and their faith in themselves, the couple moved the family to Napa, California.

An onlooker might think both men had risked a lot with these unconventional choices. Winiarski left the distinguished life of letters that had appeared to be his destiny and chose to become a winemaker. Fay’s leap of faith was planting Cabernet in the Stags Leap area. When his vines went into the soils of that “cool” region in 1961, Cabernet Sauvignon wasn’t even a “thing” in the Napa Valley. Although the variety is the very heart and soul of Napa now, at that time there were only about 600 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon planted in all of California. From a financial point of view, both men were risk-taking on long odds.

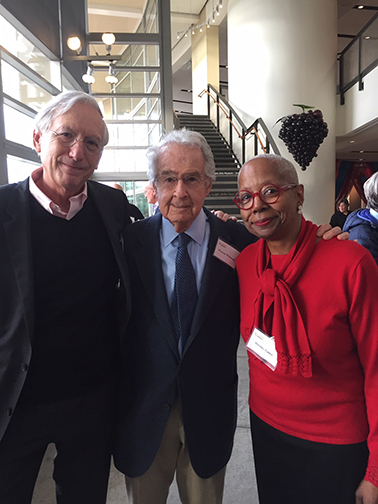

(Celebrating the donation of our papers to UC-Davis's Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection)

By the way, the winning 1973 Cabernet was Winiarski’s first commercial vintage.

Phrasing it like that might make Winiarski’s success sound easy, perhaps even a lucky fluke, but that might be analogous to implying that Nathan Fay was dropped on the summit of the Matterhorn by helicopter. In fact, both men arrived successfully to their respective destinations through dogged determination and hard work. Someone once said to Winiarski that winning the Paris tasting was like being “struck by lightning.” To which he replied, “Yes, but first we had to put ourselves in a position where the lightening could strike.”

Upon arriving in Napa, Winiarski went straight into training mode. His first job was with Lee Stewart at Chateau Souverain on Howell Mountain, where he was the second man in a two-man operation. It was an excellent place to start because Stewart was a stickler for detail. “He taught me that no detail in winemaking was too small not to command a winemaker’s full attention.” (One could say the same about the details in mountain climbing where the consequences of overlooking the minutest of them could be deadly.)

After two years, Winiarski felt he had learned everything that he could at Souverain, so he left. He was then hired as the first winemaker at Robert Mondavi Winery, the first new winery to be built in Napa Valley since the repeal of Prohibition. Robert Mondavi’s Oakville winery was still under construction at the time and the chaotic conditions offered a different kind of practical winemaking experience. A nimble mind and an ability to improvise were essential job requirements. Winiarski learned valuable life lessons there too. “Bob taught me that no goal was so lofty that it could not be exceeded.”

Winiarski compares his time at Souverain and Robert Mondavi Winery to climbing ever-taller peaks. “They were my guided lesser peaks, and Ivancie was my attempt at a solo.” Gerald Ivancie was a Colorado periodontist with wine dreams of his own. Ivancie’s initial idea was to purchase California grapes and transport them in refrigerated trucks to Denver to make wine there. Familiar with Napa Valley’s grape quality and of Winiarski’s reputation as a “man who knew about where to get good grapes,” Ivancie lured him away from Mondavi to do everything from finding the grapes to making the wine. The lessons Winiarski learned from training on the “lesser peaks,” combined with his own constant self-education, would stand him in good stead.

Winiarski compares his time at Souverain and Robert Mondavi Winery to climbing ever-taller peaks. “They were my guided lesser peaks, and Ivancie was my attempt at a solo.” Gerald Ivancie was a Colorado periodontist with wine dreams of his own. Ivancie’s initial idea was to purchase California grapes and transport them in refrigerated trucks to Denver to make wine there. Familiar with Napa Valley’s grape quality and of Winiarski’s reputation as a “man who knew about where to get good grapes,” Ivancie lured him away from Mondavi to do everything from finding the grapes to making the wine. The lessons Winiarski learned from training on the “lesser peaks,” combined with his own constant self-education, would stand him in good stead.

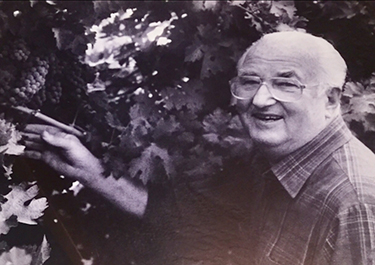

(Nathan Fay, 1914-2001)

By the time Ivancie came along with his consulting proposal, Winiarski had been poking around many of Napa Valley’s nooks and crannies looking for the ideal spot to grow top-quality Cabernet. He and Barbara had already purchased and planted Cabernet on a three-acre property up on Howell Mountain, but he had doubts about whether that land could produce the refined style of wine that he held in his mind’s eye.

Enter Nathan Fay.

Fay was a grower, not a commercial winemaker, but he made a little hobby wine from the vines he’d planted back in ’61. When Winiarski came by to talk about an irrigation system in 1969, the affable Fay asked if he would like to taste his 1968 vintage wine. It was homemade, only a year old, but vinified from Fay’s Stags Leap Cabernet grapes. Winiarski might not have expected much, but “even before the first sip, just from the aromatics of the wine in the room, the wine spoke to me,” he has recounted. “It said, ‘Listen to me, I’m talking to you’…(and) I said, ‘That’s it; that’s the grape that satisfies what I believe to be the most expressive of the variety.’”

For Winiarski, “most expressive” meant that those Stags Leap grapes had the potential to not only reflect their regional distinctiveness, their terroir, but could also achieve widely recognizable “classical characteristics of greatness, if properly vinified.” Stags Leap District was the Cabernet Sauvignon sweet spot he had been seeking.

For Winiarski, “most expressive” meant that those Stags Leap grapes had the potential to not only reflect their regional distinctiveness, their terroir, but could also achieve widely recognizable “classical characteristics of greatness, if properly vinified.” Stags Leap District was the Cabernet Sauvignon sweet spot he had been seeking.

(Warren Winiarski and Dottie at Stag's Leap Wine Cellars in Napa)

By chance, the Heid Ranch adjoining Fay’s property was available. So, sparked by Winiarski’s “aha!” moment over that homemade wine, the Winiarskis sold their Howell Mountain property. With the help of that seed money, contributions from Winiarski’s mother, and a few other investors, the Stag’s Leap Vineyard “adventure” began in 1970.

Through the years, Winiarski and Fay often talked about their shared affections: wine and agriculture. They also worked together on establishing the historic Napa Valley Agriculture Preserve in 1968, the first legislation of its kind in the United States. The preserve continues to protect the agricultural nature of the valley by restricting development.

But the two men had vastly different ambitions about winemaking. Winiarski wanted to make one of the world’s best wines, and he most assuredly did. Fay never went in that direction. Although people would try to interest him in building a winery, he preferred working in the vineyard, selling his grapes to others, and making wine primarily for his own enjoyment.

Winiarski later reflected on his friend’s decision to plant what he planted, where he planted it, and when he planted it. “Nathan possessed real daring and pioneering spirit to do what he did. It’s lonely, if you think of it…You might say a whole decade passes before the sense of what this land can produce when planted to this varietal is at all visible. That’s about a third of a man’s adult working life…This is a highly venturesome, speculative endeavor. But while the risk of missing the mark is great, the promise of a new, beautiful, sun-lit success sustains the spirit.”

“People did recommend to Nathan that he plant Cabernet,” Winiarski said. “But I don’t think any of these people were certain of the outcome. How could they be? ...The important thing is that no matter how good one’s recommendations may be, they do not change the character and the magnitude of the risk and the quality of daring that was involved in cultivating an untried variety in this unproven area.”

This column was originally commissioned by Warren Winiarski for warrenwiniarski.com and is published here with his approval.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner art by Piers Parlett