Steve Edmunds isn’t a graduate of UC Davis wine school. He doesn’t own a winery or any vineyards, nor does he make, what he calls, “important" wines. Ask wine drinkers if they’ve heard of him and, most likely, you’ll be met with blank stares. Yet there are those who have taken notice. Wine critic Esther Mobley writes, “Steve Edmunds has been producing some of California’s most soul-stirring wines for the last 33 years under his Edmunds St. John label” (San Francisco Chronicle, 2018). And longtime fans know that what this unheralded winemaker does is more important than what he doesn't do.

Edmunds, a country-folk musician with two commercially-released albums, approaches winemaking with a musician’s sensitivity. He pays close attention to how a wine makes him feel — if it stirs his emotions, he knows he’s on to something. This led-by-the-heart winemaker wants to create, as he says, "something that just grabs people."

Edmunds began his wine career nearly fifty years ago, selling wine and winemaking equipment, along with a brief stint as a mailman. In 1985 he decided to make his first wines, turning to the great varieties of France’s Rhône Valley: Grenache, Mourvèdre, Syrah, and Viognier. The Edmunds St. John roster has since grown to include other atypical-for-California grapes like Gamay, Graciano, Grenache Blanc and Vermentino. For decades, Edmunds has sourced his grapes from some of the most respected growers in California. His light hand in the winemaking process allows the grapes, and then the wines, to speak of where they come from. One of Edmunds’s proudest moments came in 1987 when François Peychaud, owner of Bandol's iconic Domaine Tempier declared, “la terre parle” (the earth speaks) after tasting Edmunds' Mount Veeder-sourced Mourvèdre.

Grape Collective caught up with the soft-spoken Edmunds to talk about his decades-long stretch in the wine business and the constant struggle to get his understated wines noticed in a market saturated with big, bold California Cabs.

Lisa Denning: Can you tell us a little bit about your background and how you got into winemaking?

Lisa Denning: Can you tell us a little bit about your background and how you got into winemaking?

Steve Edmunds: It was a long time ago. I've actually been in the wine business going on 48 years. And when I started I was working for a company that sold equipment and supplies to people that made wine and beer at home. And I really didn't know anything about wine, but I made beer at home. And they said, "You'll need to learn about making wine." And I said, "I'll figure it out."

And I had a friend who drove a delivery truck for a wine importer in San Francisco. When he learned that I had gotten this job he said, "If you're interested, I'll set up a tasting for you. And I'll teach you what I know." He really loved good wine and he had access to it at very modest prices, since he worked for the company, and had nobody to share that enthusiasm with. And I said, "Sure, that sounds great."

So he set up a tasting for me on a Saturday evening and that was really the first time I had ever tasted wine. Up until that point, I thought of wine as this stuff that everybody had bad things to say about and which was something that you drank for the alcohol. You put it in your mouth and you swallow it. And if it's not too bad, then you do it again, and at a certain point you have to decide whether to stop or get up on the table and dance.

And he taught me to smell. That was the primary thing that really changed everything. And then when I put the wine in my mouth, not to just swallow it but to move it around and let it touch all the surfaces inside my mouth, draw a little air in to kind of wake up the volatile components in the wine. And it was like somebody had turned a switch on that just lit me up. And I felt I was discovering something that was really exciting and moving. And I became an instant fanatic.

And I had to make a certain amount of wine every month as part of that job. You could make wine from concentrated grape juice, which is what they used and sold. But just to be able to be conversant, to tell people, if they were having problems with the wine, to coach them through the process. And then very quickly, I got involved in the retail wine business because the thing I was doing was really not all that exciting.

And this was in 1972 and ’73. And the California wine business was just really beginning to come alive after all that time after prohibition when it was really a sleepy little business. There were new wineries starting to bring their first wines out. People like Stag's Leap and Chateau Montelena. And I was one of the first people in the business who was out there finding them and getting excited about what they were doing and bringing the wines back to the store that I worked in. I started to really sell those wines.

I continued to make wine as a home winemaker for a long time. I was in the retail business for about 13 years and I took a hiatus from full-time involvement for a few years at a certain point and got a job as a mailman. But I moonlighted in the wine business. And I went through a divorce from my first wife and sometime after that met my second wife, Cornelia, who is my wife currently. And at some point she said, "Well, you don't want to be a mailman for the rest of your life, do you?" And I said, "No, I guess not."

And so we decided to try and think about something that I could do that would take advantage of my knowledge and my enthusiasm about wine. And I decided really in retrospect, cavalierly, to start a wine producing operation. And I had no idea what I was going to make. And I spent the first several months of 1985, which was the year that we began, just tasting and keeping track of what I was tasting and trying to pay attention to what moved me, what I responded to.

And at some point in the spring when I was kind of narrowing it down — and I was narrowing it down to Rhône or Italian varieties — I started seeing articles in various trade journals about Rhône grapes, about Syrah in particular. There was a letter to a wine publication from a fellow named Robert Mayberry who I subsequently met and really enjoyed the time that I spent with him. He was suggesting that someone in California should take grapes from old plantings of Grenache, Syrah and Mourvèdre and try to make a Rhône style wine in California because it seemed the climate there would really lend itself to that.

And maybe use whole-cluster fermentation and age the wine in older wood, but try to make something in that style. It was just the timing of seeing all of these articles within a very short time, and having narrowed down my focus to the Italian and the Rhône varieties, and knowing from the time that I had spent in the business thus far that I would be able to find with pretty certain likelihood Carignan, Mourvedre, Grenache and probably Syrah. And also knowing that I would be unable to find Nebbiolo or any of the other Italian varieties I was interested in other than maybe Barbera.

My wife and I were having this conversation one night when we lived around the corner from Chez Panisse and we walked over to have dinner and I was telling her all this stuff. And we were waiting for a table and having a glass of wine and they called us up to our table and we sat down and they brought the menu and the wine list. And on the wine list was a Syrah from Qupé Winery in Santa Barbara County.

And in the meantime, Cornelia and I had been having this conversation in which I saying, "I really think this is what I want to try to focus on." And they brought this Syrah to the table, I had ordered a bottle of it, and I stuck my nose in the glass and it was like the message from above saying, “This is what you're going to do.” It was really delicious. And I just said, "Yeah, we can do this here." Anyway, that's how I got started. It was a process.

Were you a member of the Rhône Rangers that formed in the mid '80s?

Well, here's what happened or at least my recollection of what happened. Back in 1987 in the summer there was a thing that happened every year, the California Wine Tasting Championships, and it was held at the Greenwood Ridge Winery in Mendocino County. And two of the participants were myself and John Buechsenstein who was the winemaker for McDowell Valley at the time. And we actually tied for first place in the professional, individual category of the tasting championship. We became friends and we talked about people in California making wine from Rhône varieties and how hard it was to get anybody's attention. Because this was just when everybody was starting to really get completely carried away with the idea that California was for Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. We decided to try to hold an event, just to get together, for producers in California who were working with Rhône varieties.

And as near as we could tell at that time, there were less than two dozen winemakers in California working with Rhône grapes. And so we invited everybody to a get together at a restaurant in Berkeley called Lalime's. That was in December of 1987 and almost everybody came. I think we had maybe 19 out of 21, something like that. And a lot of the winemakers were toiling away making whatever it was that they were making, having trouble selling all their wine and thinking we really need to get a marketing organization together.

And the idea was tossed around about doing that and some people were feeling much more casual about it than others and rebelled at the idea of being very organized about it. And the idea of what to call such a group came up and nobody had anything really very interesting to suggest. It was just an idea that came to life that evening. Very shortly after that I was visiting a friend at a retail store and at that time I was making a wine that was a blend of Grenache, Mourvedre, Syrah. It was called Les Cotes Sauvages.

And he told me, I think you should change the name of that wine. You should call it the Rhône Ranger. And I immediately said, "No, that's the stupidest thing I ever heard." But I said, "That would be a great name for this group of winemakers." And so the next time that I communicated with the other people who had been at the dinner, I sent everybody a note and I addressed it “Dear fellow Rhône Rangers.” And at some point, I had a conversation on the phone with Randall Grahm from Bonny Doon about something, grapes probably, and I mentioned to him this guy coming up with that name. And I said, "I think it's a pretty cool marketing name." And I could hear the gears turning in Randall's head and the next thing I knew he was on the cover of the Wine Spectator dressed as the Rhône Ranger back in April of '88. So, it was all in motion pretty quickly.

That's really interesting. I know the group disbanded and then it got back together? Are you currently a member?

I think so. They stopped doing their annual tasting in San Francisco, which was probably smart because it was just getting unwieldy, it was a huge event. It was a drunken bash and people would go there and they'd start tasting at noon, and by four o'clock, they'd be staggering around from table to table. And we all just wanted to get out of there. On your website at the bottom, it says la terre parle. Can you tell us the significance of that?

On your website at the bottom, it says la terre parle. Can you tell us the significance of that?

Sure. It's French for the earth speaks. That phrase was uttered by François Peyraud from Domaine Tempier who visited my winery back in February of ’87 with Kermit Lynch. Kermit and I got into the business in the same year back in ’72. And we had been friends for quite a while, when I was in retail at the same time that he was and we would send each other customers if they were looking for something we didn't have.

And when I made the first wine from Mourvèdre grapes that I was working with at that time, which were from a wonderful planting from Mount Veeder in Napa, Kermit wanted to taste it. And so we got together and he tasted it and he was very intrigued. And he said, "Would you mind if I take a sample of this to the Peyrauds at Domaine Tempier, I think they'd be really fascinated to know somebody in California is trying to do something like what they're doing."

And so I did and then a couple years later, François shows up with Kermit and they come over to visit and I was anxious to have them taste everything in the cellar. I saved the Mourvèdre for last. And wine after wine after wine after wine, going around the cellar I would watch François very closely when he tasted the wine and there was no immediate reaction at all. Then finally we got to the Mourvèdre from '86 from Mount Veeder and when he brought the glass of that to his nose, he immediately came to attention and he sniffed for a very long time. And at some point his head came up and his eyes rolled back in his head, and he took in this big breath. And then he said, "La terre parle." And everybody just went, "yeah."

That's great.

It was quite a moment. It was pretty fun.

How would you sum up your philosophy of winemaking?

I'm not sure if I have one. The most important thing is, how good are the grapes? And that depends on what the variety is, where it's planted, who is farming it, whether they know what they're doing and how they take care of the vines and the grapes and the soil. Once the decision to pick the grapes is made, the winemaking, unless something goes wrong, is really very straightforward.

The most important thing that I do is just keep in communication with the grower, spend a lot of time with the vines and pay attention to how they're doing what they're doing, what kind of shape the grapes are in, what the weather's doing and all that. And then when the ripening time comes, to make a good decision about when the fruit is ripe, and the only way to make that determination, I think is certainly by tasting the fruit. There are numbers that I keep track of just as parameters or guidelines.

Most important to me is the pH because it's usually an indicator in the progression that it makes, which starts out very slow and gradual and then at a certain point becomes much more dramatic. And at that point, when it starts to go up more vertically than gradually that's the point really past which you should have picked, or before which you should have picked. And it typically coincides with the point at which the flavors are really all balanced and on point and the flavors are pretty focused. And they're lively and my nervous system responds in a certain way.

And it will vary from year to year. And it can be tricky to get the actual time when the grapes are picked to coincide with that point at which everything is really right where you want it. But the more years that have gone by, the better I think I've been able to hone in on that. And again, once that decision is made and the grapes are picked then the winemaking is really simple.

How would you describe the style of your wines to someone who's never tasted them?

They are wines that I think are a combination of refreshing, which tends to make them beckon you to take another mouthful, and savory. They're not meant to be important or unicorn wines or trophy wines or any of that stuff. They're meant to drink and to give pleasure. Can you tell us about the wines you make and the vineyards the grapes come from?

Can you tell us about the wines you make and the vineyards the grapes come from?

With the exception of Shake Ridge Vineyard, (photo at right), where all of the varieties were there before I started to work with any of the fruit, the other vineyards are two Gamay sites that we’re working with, both of which were planted at my request.

The Witters Vineyard planted back in 2000 is a volcanic site, it's at about 3,400 feet elevation, which makes it one of the higher vineyards in California. And the idea of planting Gamay in that site was at that elevation it would be cool enough for Gamay, which ripens very early, to get it to maturity, without having so much sugar that you'd have a high alcohol level in the wine. I think Gamay makes its best wines when it's able to ripen and give you somewhere between maybe 11 and 13% alcohol. And much of California is just really too warm to expect that to happen with any consistency.

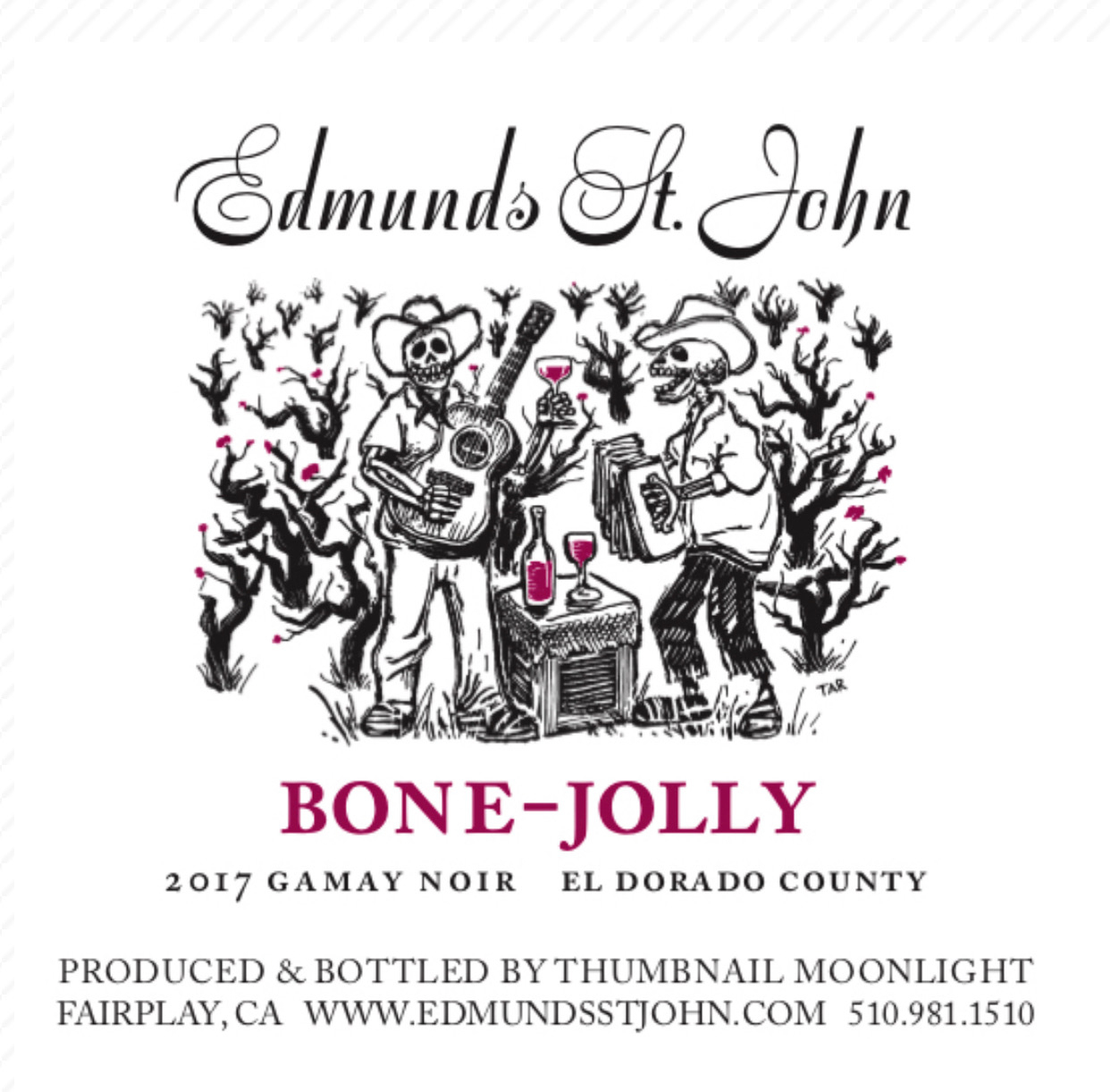

And we were able to make really fairly light, fresh, pretty wines from there. The odd thing about Gamay and that site is that when the vines were young, the wine seemed to have almost no tannin at all. The aromas were good, the acidity was fabulous, and the flavors were all really terrific. But the texture was lacking. And it was a little strange. And then five years later, there is a site at which the Barsotti family for years had been raising apples and they decided they wanted to put in some grapes and so we put Gamay there and the soil is granite, decomposed granite. It's a pinkish, slightly purply color granite soil. And we made the first wine from those vines in 2007. And right off the bat the tannin was there that wasn't there at the other site. Eventually I decided that I would use the Gamay from the original site only for rosé because it just made wonderful rosé. And the red was not anywhere near as compelling. And then the granite site would be the only site for the red wine. And you call those wines Bone-Jolly, a play on Beaujolais. Who thought of that name?

And you call those wines Bone-Jolly, a play on Beaujolais. Who thought of that name?

I did. The story with that was when I was in my retail period, as the buyer for the store that I worked at for several years, I would frequently get samples of wines to taste and there were more than I could possibly find time to taste at the store with the staff. I would just take some of them home and if one of the samples that I took home was a Cru Beaujolais and it was good, and mostly they were, just the smell of that wine would make me feel so happy. It's such a joyous wine. And I felt I was jolly right down to my bones and that was the source of the play on Beaujolais, the Bone-Jolly thing.

I love that! And tell me about your other vineyards?

The other two sites that we get fruit from, one is the Fenaughty Vineyard, also in the Apple Hill area in Placerville, as are the Witters and the Barsotti. Fenaughty's at about 2,800 feet, it's the same soil as at Witters. Its volcanic clay-loam. It's high enough at 2,800 feet to still be really quite cool and produce wines with great aromatic character.

And what we're making from Fenaughty these days, and since about 2011, is a white wine made from grapes that were also planted for me, Vermentino and Grenache Blanc. And then the other site is the Shake Ridge Vineyard that the El Jaleo comes from. It's a warmer site. It's between 13 and 18 hundred feet elevation down in Amador County, east of Sutter Creek about six miles. It’s farmed by a woman named Ann Kraemer who does the most meticulous farming I've ever seen. It's just a beautiful place. Ann makes wines with a lot of character and a lot of wonderful flavor.

And what are the grape varieties in the the current vintage of El Jaleo (2017)?

Let’s see if I can remember the numbers right. 32% Mourvèdre, 28% Grenache, 26% Graciano, and 14% Tempranillo.

That's an interesting blend.

The idea was to take essentially the varieties that are used in the red wines of Rioja and put together a blend to make something from California that was somehow evocative of the wines of Rioja. Rioja does not grow Mourvèdre, they grow what they call Mazuelo which is Carignan. I've worked with both Carignan and Mourvèdre and Shake Ridge doesn't have Carignan and I thought well Mourvèdre is close enough and it's a better grape anyway.

So it worked.

Yeah, I think it works really nicely. Where these grapes are grown in Rioja, there's limestone and in Shake Ridge, no such luck. The grapes of Tempranillo in particular, but the Grenache and Mourvèdre tend to be higher in pH. So they tend to be a little heavy and the Tempranillo and Grenache are especially tannic there. Graciano is much lower in PH, really expressive, has tremendous acidity, very spicy. And I was astonished the first year that we worked with these grapes the way that the Graciano would pull together the other pieces of the puzzle into a shape. And it was suddenly transformed. So we've now worked with the grapes for four vintages. And each year, there's been more Graciano and each year that we've done that the wines have gotten better. Can you tell us about your relationship with your growers?

Can you tell us about your relationship with your growers?

I've been working with Ron Mansfield since 1988. He farms all the El Dorado County grapes that I’ve used for a little over 30 years now. And when I started to work with Ron, he had a small amount of Syrah planted and basically, he had two or three rows of each of about eight or nine different grape varieties. He had planted them on a ranch that he was managing.

His principal business at that point was growing orchard fruit. He grows apples, pears, peaches, nectarines, he grew cherries for a while, and plums. And I think he figured out that grapes were more lucrative than almost any of those, and that they were going to become more and more important. So he put in these various rows of things and then was so busy with the rest of his business that he just ended up selling the grapes to home winemakers and not thinking about it that much.

And I came up to the foothills in ’88 looking for people to grow grapes for me. Because in Sonoma and Napa for the most part, nobody wanted to talk to me because nobody knew who I was. They could get really good money for Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay and stuff like that and they were not willing to bet on Mourvèdre or Syrah or Grenache because they didn't feel like there was enough of a market for it to make it worth their while.

(Photo: Witters Vineyard)

Ron offered to sell me the Syrah that he had that first year and said, “If you think it's really good and you want more, I'm willing to graft over the other rows to Syrah for you, and we can work on a long term basis.” And I said, "That's very attractive. I'll consider that." I made wine from that Syrah the first year and I was already working with Syrah from the Durell Vineyard in Sonoma Valley, which for quite a number of years had became one of the most highly regarded Syrah plantings in California.

And the Syrah from the Fenaughty Ranch, which is where these vines were planted that I bought the grapes from Ron from, the wine was so utterly different. The stuff from the Sonoma Valley was big and meaty and very smokey and quite dramatic. And this stuff from the Fenaughty place was much more ethereal and perfumed and much lighter, and it ripened much later. But it was very intriguing and I just I didn't know how to think about it.

And I invited a colleague to taste it. He had run a retail store, actually my first retail customer, and made his own wine from grapes grown down in Amador County and it went on to become Domaine de la Terre Rouge, a guy named Bill Easton. He came over to taste and he smelled it and he tasted and he said, "It tastes like Côte Rôtie from Robert Jasmin and I went, “You're right, it does.” So I went back to Ron and I said, "Sign me up. I want you to graft this stuff over." So we did that. And in the meantime, he was getting more and more growers of orchard fruit who were interested in switching over to grapes because the globalization of fruit was really driving the price of their tree fruits down. And they were obviously in a place where good wine grapes could grow. So a farmer would go to Ron and say, "Can you put in some grapes?” And Ron would call me up and he say, "Would you go over to this site with me and have a look at it. I want to see what you think might make sense to plant there."

And in the meantime, he was getting more and more growers of orchard fruit who were interested in switching over to grapes because the globalization of fruit was really driving the price of their tree fruits down. And they were obviously in a place where good wine grapes could grow. So a farmer would go to Ron and say, "Can you put in some grapes?” And Ron would call me up and he say, "Would you go over to this site with me and have a look at it. I want to see what you think might make sense to plant there."

So he was a) trying to figure out what to do about planting grapes in El Dorado and b) he knew I was looking for grapes, so he's trying to cultivate a customer and I was an easy mark. I said, "Yeah, put some Syrah there," and he said, "Well, would you buy it?" And I said, "sure." So that's the way things went for quite a while and the planting in Fenaughty got greatly expanded.

And I knew lots of other winemakers who were willing to buy a little Syrah or a little Marsanne or whatever it was he was planting. And then he started planting Grenache, Rousanne, and Viognier and so forth and his clientele started to really increase. And I went to probably four or five different sites with him to talk about what to plant and I ended up buying fruit from most of them, almost all of them.

(Photo: Mourvedre grapes)

And then back in 1999 he wanted to go to Paso Robles to see what was going on down there because he was hearing great things about Tablas Creek and other people. And so we drove down together and spent the day. He came back to my house and had dinner afterward. On the way down there he was talking about this apple producing property at 3,400 feet elevation that was owned by this guy, Bob Witters who wanted to take out apples and put in grapes.

And I had been wanting to get somebody to plant Gamay for me for a really long time but I had no idea how to do it because Gamay was the antithesis of what California thought of as the appropriate wine to make. It was certainly the last thing in the world they thought they could get big points for with Robert Parker. And I started talking to Ron about Gamay for that site because it was so high and it was so cool. And he was very intrigued but he said, "Isn't that what was planted at this other vineyard that you started working with where they grafted it all over to Pinot Gris for you?” And I said, "No, that was Valdiguié but it's been misidentified as Gamay a for a long time. Valdiguié ripens at the end of the season, Gamay ripens at the beginning, they're completely different.

So when we got back to my house, I opened up a couple bottles of Cru Beaujolais that were actually wines that Kermit imported. And we had them with dinner and Ron just flipped. He said, "Man, this stuff is great." So he went back to Bob Witters and he said, "Here's what I think you should do." And Bob ended up planting three acres of Pinot Gris and four acres of Gamay at Witters.

And I told all my friends in the business, I'm going to make Gamay." And they all said, "You've lost your mind." But anyway, Ron and I just worked really closely because it was clear to us that we were going to benefit from each other's expertise and ability. Ron has a great ability to farm for flavor and really has done a tremendous job over the years, supplying me with fruit that I've been able to make wine from that I really enjoy and that is usually very well received in the market.

And then as far as Shake Ridge, I had just been hearing so many great things. I worked with Unti vineyards in Healdsburg for a number of years, about seven years making Rocks and Gravel. I had the chance over that period to really zero in on how to get what I felt was the best result from the grapes of theirs that I was using. And then they stopped selling any fruit at all. So I lost access to that fruit and I lost one of the wines that was an anchor in my lineup. And I had been making wine long enough at that point that I thought, "Well, this has happened before I could be upset about it or I could see it as an opportunity to do something else that I've been curious about for a long time." And I had this idea in my mind of the Rioja varieties and I didn't know whether Ann had those grapes or not.

But I called her up and I said, "I've been hearing such great things about your vineyard, I'd love to come take a look." And she was just wonderful. She said, "Come on up, I'll show you around." And then she offered me some grapes and she said, "What would you want if you could have exactly what you wanted?" And I said, "Well, here's what I'm thinking. What about a ton of Tempranillo, a ton of Grenache, a ton of Mourvèdre, and a half ton of Graciano?" And she said, "Yeah, we can do that. That's fine." And so that's where we started. She's been really wonderful. Every year I've asked her for more Graciano and she's figured out a way to make it happen — she's just incredible. She charges a lot of money for her grapes, but she'll do pretty much anything as long as she's not taking grapes away from somebody else or doing something to damage the vineyard. She's really easy to work with.

Would you say your approach to winemaking is a lot different than many other California wine makers?

It probably is. I don't have any specific intent when I start, I want the grapes to tell me what they want to be. And I just have to really pay attention and it's just tasting.

And you don’t add cultured yeast to your wine. Can you talk about the reasons for that.

No I don’t. The wines ferment pretty easily without any additions. If I get a lot of grapes that just don’t want to ferment and starts tending toward getting volatile or something, we'll take something else that's already fermenting, and we'll use a little of it to inoculate and just get the fermentation going. But once it gets underway, it’s easy.

I almost invariably am looking to make wines that are much lower in pH, which automatically ensures a healthier environment for the fermentation and the whole winemaking process. It means you don't have to use as much SO2 to it means it's just much easier. The fermentation doesn't have a lack of something to fight with, something that could have been where it needed to be if the picking had been done a little bit sooner.

Are there other winemakers that you think, “Wow, they're really doing something interesting”? I think a lot of people think that about you.

I think Tablas Creek, for a larger winery, is doing just spectacular stuff, really great stuff. I think Arnot Roberts is doing really nice things. There's a bunch of them. And no doubt there's some that I don't know that much about that are doing really good things. Hardy Wallace is doing really nice things. There's a guy named Leo Steen in Dry Creek Valley who's making Chenin Blanc that I think is brilliant. Really good stuff.

A lot of people in California, for economic reasons perhaps, gravitate to Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. You obviously made a clear decision not to do that, but there must be economic consequences. Did you ever have doubts?

Yeah, it's interesting that you phrase it that way because my thought back in 1985 was, “If I walk into a store with a Chardonnay or Cabernet to try to sell, my worry is that they'll just say, ‘Oh, another Cabernet, another Chardonnay.’” And there are people who are so established who already have everybody's attention. People who may have already made the best Cabernet that I could imagine anybody making.

When I was in retail and I tasted the first Cabernet from Warren Winiarski from Stag's Leap, I just thought, “Wow.” I was a buyer for a store and I immediately ordered 20 cases on the spot, I went back to my store and my boss said, "What are you doing?" And I said, "Don't worry, it'll be gone in two weeks." And it was. I went through 85 or 90 cases of that wine before it sold out.

And so anyways, I felt I was going to have more trouble trying to establish my credibility, particularly since I was buying grapes. I certainly didn't have the choice of where they were planted. I was just buying what I could find. I knew that the craze was really on in those days to use new oak but we were running on a shoestring. And I was trying to figure out a way to make it all work.

It was clearly an uphill fight to get people to even listen when I said, "I'm making a blend of Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah." Most people couldn't even pronounce Mourvèdre, had never heard of it. A lot of people would say to me, “How am I going to sell that?” It was like I was beating my head against the wall up to a certain point. But after two or three really nice reviews from Robert Parker, my phone started to ring and distributors wanted to buy my wine.

And it was just clear to me. When I got into the business, California wineries made everything from dry Sherry, to Champagne to Cabernet Sauvignon to Burgundy to Riesling, they made it all. And it's not that that was necessarily a great idea. But to suddenly throw everything out and just have Cabernet and Chardonnay, it broke my heart. I just felt like, I don't want to do that.

I want to do something other people aren't doing. The only way to get people to pay attention to what I'm doing is to do something that other people aren't doing. And really make something that's undeniably compelling and interesting. And really the only way that that ever worked was I got incredibly lucky that first year, and ended up working with the Mourvèdre from that planting on Mount Veeder that was such fabulous fruit.

In 1986 the wine that I made from that — that was the wine that the guy from Domaine Tempier said “la terra parle.” That was a wine that when I showed it to other winemakers who were making really expensive Cabernet Sauvignon wines and they tasted it, they would they go, “What is this? This is fabulous.” And I felt like, that's got to be enough, that's got to be where it starts. If you can make something that just grabs people like that, you've got half the battle or more already in your pocket.