Wineries come and go in California, but the current status of Ravenswood Winery is particularly sad. Ravenswood and its founder-winemaker, Joel Peterson, helped prove that Zinfandel could be a wine of structure, balance and elegance as well as power. Now Ravenswood is caught in the limbo of a billion-dollar deal between two of America’s biggest wine producers, Constellation Brands and E. & J. Gallo Winery. It appears there will be no 2019 Ravenswood, at least for now. Will the label ever return? We’ll see.

With the 47th anniversary of the day we met coming up -- it was June 4, 1973, the day both of us started as reporters at The Miami Herald -- we thought about how we would celebrate in lockdown. We wrote recently that a restaurant with a fine wine list near us was selling its bottles curbside. John saw that it had five vintages of Ravenswood’s Dickerson Vineyard: 1988, 1994, 1996, 1997 and 1999. (We had the 1989 Dickerson at the same restaurant in 2005 and it was beautiful.) The wines averaged $80, which is not nothin’, so we decided we’d give them to each other as an anniversary present and drink them on successive nights.

It was a perfect way to celebrate our meeting, at age 21, and also celebrate Ravenswood, Dickerson, and Peterson, who founded the winery in Sonoma County three years after we met.

It was a perfect way to celebrate our meeting, at age 21, and also celebrate Ravenswood, Dickerson, and Peterson, who founded the winery in Sonoma County three years after we met.

Peterson felt Zinfandels should be site-specific and his vineyard-designated Zins became justly famous. We have a special fondness for Dickerson, the man and the vineyard. The greatest Zin we had in the entire decade of the 1990s was a ’92 Ravenswood Dickerson Vineyard Napa Valley.

So we decided to give Peterson a call. We’ve spoken to him a few times over the years and have always found him charming and candid. At 73, having started a new project, he has not changed. We spoke to him in the midst of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests and asked how those of us who write about or make wine can feel good about what we do right now.

“We just all just need to get along,” Peterson said, “and one of the ways we get along is by sharing our commonality and our commonality is that we all eat and we all drink. Some of my most important social experiences have been with people of incredibly diverse and different backgrounds than my own and wine is a way of interacting that is non-controversial, that allows you to get to the controversial stuff while still being amicable, and I think it helps you reach understandings that you wouldn’t otherwise have.”

Peterson grew up in the San Francisco Bay area surrounded by extraordinary people. Both of his parents were chemists – his mother was a nuclear chemist who worked on the Manhattan Project – and they had similarly accomplished friends. Soon they began all sorts of wine and food tasting groups. One member was a psychiatrist named Bill Dickerson.

Years later, Peterson was running in a race near Domaine Chandon in Napa when he glanced over his shoulder and there was Dickerson, who did not recognize him as the boy who hung around those tastings. But once they got reacquainted, Peterson explained that he had started a winery and Dickerson said he had a small Zinfandel vineyard in Napa – on Zinfandel Lane, as it happened. Dickerson was selling his grapes to Louis Martini and was not happy about it because they were just going into big blends.

In 1981, Peterson made his first Dickerson Zinfandel.

For all of you who didn’t have the pleasure of drinking Zinfandel back then – and especially Ravenswood and Ridge -- it was such a fine wine. We’ve also enjoyed others over the years, of course, including Rafanelli and Rosenblum. We believed it could be America’s unique contribution to the fine red wines of the world (although the grape originated in Croatia). We asked Peterson what happened – how too many of them became the monstrous, sweet, alcoholic, bowling balls of wine.

“Through the ’80s and ’90s, the wine style was driven by people like me and Ridge and Joe Swan…and we were influenced by the European model,” he said. “We’d all grown up with European wines and we knew what made the great wines of Europe great and the simple word is balance, that essence between fruit and acid and interior strength.”

But in 1994, he said, critics went wild for a Zinfandel that was high in both alcohol and residual sugar. Zin makers took note. Soon after, a Zin with even higher alcohol and sugar won a double gold at a prestigious competition. And then it was off to the races. We never much liked those monsters and neither did Peterson. “You lose the character of the vineyard and you lose the vibrancy and you lose the energy,” he said.

With America suddenly more enthusiastic than ever about Zin – the real thing, not White Zin – Peterson began to produce a popular-priced Zin called Vintners Blend. By the end of the ’90s, a man who planned to produce a small amount of highly personal wine was making a million cases a year. Ravenswood went public in 1999 and then was sold to Constellation in 2001 for $148 million. Peterson remained with Constellation in various executive, winemaking and consulting roles until last year.

He added: “Some of the most successful wines I made at least in terms of the wines I’ve been able to evaluate with age are the wines I made between 1987 and 1999. Those wines have held up very nicely and are still very pleasurable to drink today.”

We were delighted to hear that, since those were basically the years we’d just purchased. We asked if he remembered any of our vintages in particular. Like every winemaker we’ve ever met, he remembers every year like it was yesterday, but he most wanted to talk about our oldest, the 1988.

“The ’88 is interesting because ’88 was a fairly cool year and it was really hard for others, but not for Dickerson, which tends to ripen relatively early,” he said. “I was still adding stems in ’88, which tended to fix color better and provided tannins. Dickerson can be fairly soft.” With all of that as background, we began our own journey down memory lane. We started with the youngest, 1999, and moved to the oldest, 1988, which was the year before we had our first child, Media.

We drank each over several hours, with and without food. Each was lovely, still with good fruit and plenty of acidity. Our favorites were the youngest and the oldest. Fortunately, the 1988, which we had on our actual 47th anniversary, was the very best.

The ’99 was notable for its great structure, truly a wine of elegance and class, a sophisticated Zinfandel. “It smells like grapes and earth,” we wrote in our notes. “Black cherries, chocolate, black pepper.”

Some of our notes on the ’88: “Smells like crushed dried rose petals. Still quite vibrant on the nose, but clearly some age. It’s kind of dusty. Great acidity, tobacco and tar. Like sipping wine through a straw in the ground. This is the best. It has great acidity at the beginning, middle and end that just knits everything together. There’s still plenty of fruit. It’s not too old but it’s also not going to get better. It’s bright. It’s a beauty. It’s not fragile. There’s a certain hardness about it that is surprising and very attractive. So easy to drink. Elegant. A beautiful wine, even now.”

And, by the way, it was just 13 percent alcohol, low by today’s standards.

In 2013 in Sonoma, Peterson started Once and Future Wines, where he makes 3,200 cases – including Zinfandel, naturally -- by hand. “I absolutely love what I do,” he said. “Ravenswood became a million-case winery. And when you’re running a million-case winery you don’t actually make wine anymore. You don’t really get your hands dirty. Really what I wanted to do was make wine – physically make wine again. And I wanted to work with the vineyards I loved. So I’ve gone back to really primitive winemaking. I resurrected some of the redwood fermenters I put in cold storage in 2001, the same ones I made wine in in 1994. In many ways I’m making wine for me.”

The future of Ravenswood is not clear. Constellation sold more than two dozen brands, including Ravenswood, to Gallo in a blockbuster deal last year that still has not closed. Constellation said at the time that it wanted to focus on “premium” brands. So Ravenswood is in limbo. We asked Constellation and Gallo if there would be any 2019 or 2020 Ravenswood. Constellation said it “has no information to share on the 2019 vintage” and that we should contact Gallo. A spokesman for Gallo said: “Numerous brands will join the Gallo portfolio as part of the modified agreement with Constellation, pending regulatory clearance. That being said I can reiterate that Ravenswood is one of the brands we plan to acquire from Constellation, pending FTC approval.”

We asked Peterson how he felt about all of this. “When you sell a company it belongs to someone else,” he said, and he is optimistic that Gallo will do good things with the brand. “But mostly,” he added, “the whole thing makes me sad. I had hoped that Ravenswood would become a legacy winery. That didn’t happen, but it did help fund my son’s winery -- Bedrock Wine Co. -- and lead me back to the core element, hands-on winemaking, which I am doing at Once and Future. That is a legacy of sorts.”

The fate of the Dickerson vineyard is unclear as well. We struck up an email friendship with Dr. Dickerson and then met him at our Vintners Open That Bottle Night in St. Helena in 2000. He brought two amazing Zinfandels: a 1916 from Italian Swiss Colony and a 1947 given to him by Louis Martini. The local newspaper ran a picture the next day of Dickerson uncorking the 1916 wine with Dottie’s help.

In 2004, Dickerson and his wife died in the tsunami that hit Thailand, where they were on vacation. Dickerson vineyard remains a Zinfandel vineyard – apparently the last on Zinfandel Lane -- and Constellation, for now, still controls the fruit, although it doesn’t own the vineyard. We said to Peterson that we guess that means there is no Dickerson Zinfandel being made at the moment. “Ahhhh. Wrong,” he said, and then he laughed. It turns out that the current owners of the land get a bit of fruit for themselves, some of which they sold to Peterson. A small amount of Dickerson is in tanks at Once and Future. It will be released in March.

We told Peterson to save us a bottle.

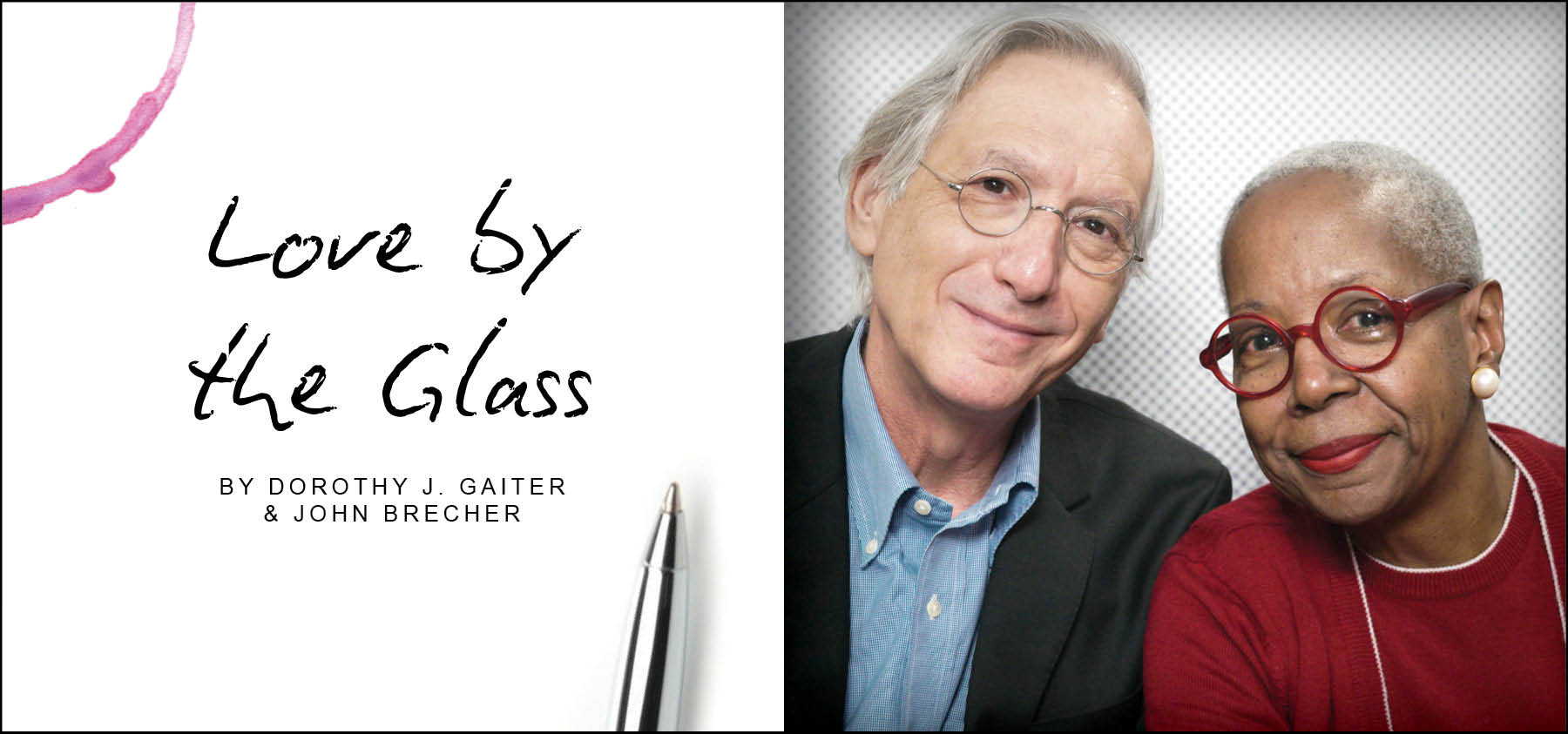

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective.

Banner by Piers Parlett