Oregon's Willamette Valley has become one of America's leading wine-producing regions. With more than 20,000 acres of vineyards and over 400 bonded winemakers, this AVA has come a long way since the first Pinot Noir vines were planted back in 1965 by David Lett of Eyrie Vineyards. Pinot Noir, of course, is the predominant wine produced in Willamette Valley, having found a special place in the challenging, cool climate of Oregon. The mid-1980s were kind to Willamette Valley, and its Pinot Noirs began to receive the recognition they deserved. The world took notice of their quality, and Oregon was soon trailing behind Burgundy.

Kentucky-born Ken Wright found his way to Oregon in 1985, leaving behind his job at Talbott Vineyards. Though his incipient years as a Willamette winemaker were rocky, he would prove to be pivotal in the AVA's growth and evolution. He would introduce sorting lines to ensure quality in the grapes that entered into the fermentors. He began using dry ice to cool grapes before the onset of fermentation, too. After selling his first winery, Panther Creek, Wright established Ken Wright Cellars in 1995, beginning his focus on single vineyard Pinot Noirs.

Wright soon noticed a pattern. Grapes grown in volcanic soils led to more fruit driven wines, whereas grapes from marine sediments led to greater floral and spice notes.

His obsession with vineyards and the signature they imparted on wines did not just end there. It led him to co-establish an impressive six sub-appellations within northern Willamette Valley. These subregions, Yamhill-Carlton, Chehalem Mountains, Ribbon Ridge, Dundee Hills, McMinnville, and Eola-Amity Hills regularly appear on his wine labels.

Megan Stypulkoska: Can you tell us about your background as a winemaker, how you got started, and what drew you into wine?

Ken Wright: Well, I was actually in the heartland of great wine country, Lexington, Kentucky. And going to school there, I was working my way, working at a restaurant, a great restaurant at the time, called The Fig Tree. The restaurant was terrific, they had a great wine list, but the staff essentially were all kids in college, and none of us had much money, had never had an opportunity to try the wines that were on the list. They were too expensive for us. We had staff meetings and the owner of the restaurant got really upset with us because of the poor sales of the wine list. And we all looked at him and said, "You know, we don't know what to say. We've never had the wines, it's difficult with our experience to talk to them and speak to them."

Ken Wright: Well, I was actually in the heartland of great wine country, Lexington, Kentucky. And going to school there, I was working my way, working at a restaurant, a great restaurant at the time, called The Fig Tree. The restaurant was terrific, they had a great wine list, but the staff essentially were all kids in college, and none of us had much money, had never had an opportunity to try the wines that were on the list. They were too expensive for us. We had staff meetings and the owner of the restaurant got really upset with us because of the poor sales of the wine list. And we all looked at him and said, "You know, we don't know what to say. We've never had the wines, it's difficult with our experience to talk to them and speak to them."

And good on him, he took that to heart and he said, "Fair enough. At these staff meetings going forward, I'm going to pick a region, and we're going to taste every wine from that region until we work our way through that entire list." And it was a great list, a really great list. For Kentucky, by far the best list in that region. To give you an example, we had every bottling of the '71 DRCs on that list. Every one. And it was just terrific wines from around the planet.

And so we did that and I was amazed by the quality and how great wine could be. I had no idea. And I got very interested, learned everything I could, tried everything that I could get my hands on. Of course, there was no real wine industry back then in Kentucky. There really still shouldn't be, but there is.

I ended up starting some wine appreciation classes while I was in school, with a friend of mine who was a roommate. And he was a graduate horticulture student. So he and I did that for two years. Actually, his masters thesis was on the cold-hardiness of vines native to Kentucky, which made him our resident expert, though no one cared then and they still don't. But the university was curious about whether or not there would be any vines, any wine varieties that might work in Kentucky. So we actually planted vineyards for them, for the university. It was a horrible failure. The diseases in Kentucky, because of the humidity, are crazy.

The humidity drives black rot and many others, and the chemistry you would have to use to combat those disease is even worse. It's really a non-starter, honestly. It was a good lesson. You know, failure's good. Then I was making wine there in Kentucky from purchased grapes that was just god-awful. Undrinkable.

But anyway, it became clear to me that I loved everything about it. I loved having the vineyard, designing it, tying it, nurturing it, as physical as it was. The whole process of fermentation was fascinating to me. So I decided, you know, I was in political science pre-law sort of curriculum and I decided to just forget about that and sold everything I had and drove out west in a VW van with my then girlfriend to Davis. UC Davis. So I enrolled there. We had just enough money to make that happen. And then I took all the viticulture courses, all the winemaking courses at Davis. And then ended up getting into the industry in '78, there in California.

And I was very, very fortunate, my first job was making wines for two companies, Ventana and Chalone, and I don't know how old you are, but-

I'm 24.

Well, then you could not possibly know what Chalone meant. Well, Chalone was by miles, by miles, the most advanced winery in the United States, by miles. And they're making the best wines, at that time, period. At that time it was under the direction of Dick Graff, who was an amazing individual, a great mentor. And he was pushing the edge of understanding of fine wine, big time. I was was very fortunate to land in that spot as a young person. And he started a group called the Small Winery Technical Society.

Because I was making wines for them, I was invited to be part of that and it was an amazing group of people. We met at Mount Eden every month and the group included Rick Foreman from Napa, Steve Kissler from Sonoma, Josh Jensen and, of course, Steve Doerner. That's when I first met Steve. Josh Jensen and Steve Doerner from Calera. We had Rick Sandford and Berno Delfanza in Santa Barbara. Mary Brooks from Acacia, which was quite the producer at the time. And all of the Chalone properties, of course, were involved in those meetings and the research that we conducted both in the winery and the vineyard. And we got two French producers in Burgundy mimicking our work and trying to replicate what we were doing to see if the results there were the results we were getting. So essentially when we started that grid, that was when the fax was first invented. So because I was the youngest in the group and the least experienced, I was elected to be the recorder of the meetings and then the one who would then communicate through the fax.

We did quite a bit of work there. It was a great opportunity for me to be around people who were very successful at the highest levels of our business and just to be a sponge, you know? So I was in the California industry there in '78 til '86. So after doing the time with Chalone, in 1982, I was offered an opportunity in the Carmel Valley by a family that had a lot of property there, to develop vineyards and winery for the family. And that was Robert Talbott. And so I was hired by the mom and dad to work with their son, Rob, in developing that business. And a little over four years later, we had gotten to the point where he was ready to take over and I was ready to start my own thing in Oregon, which I did.

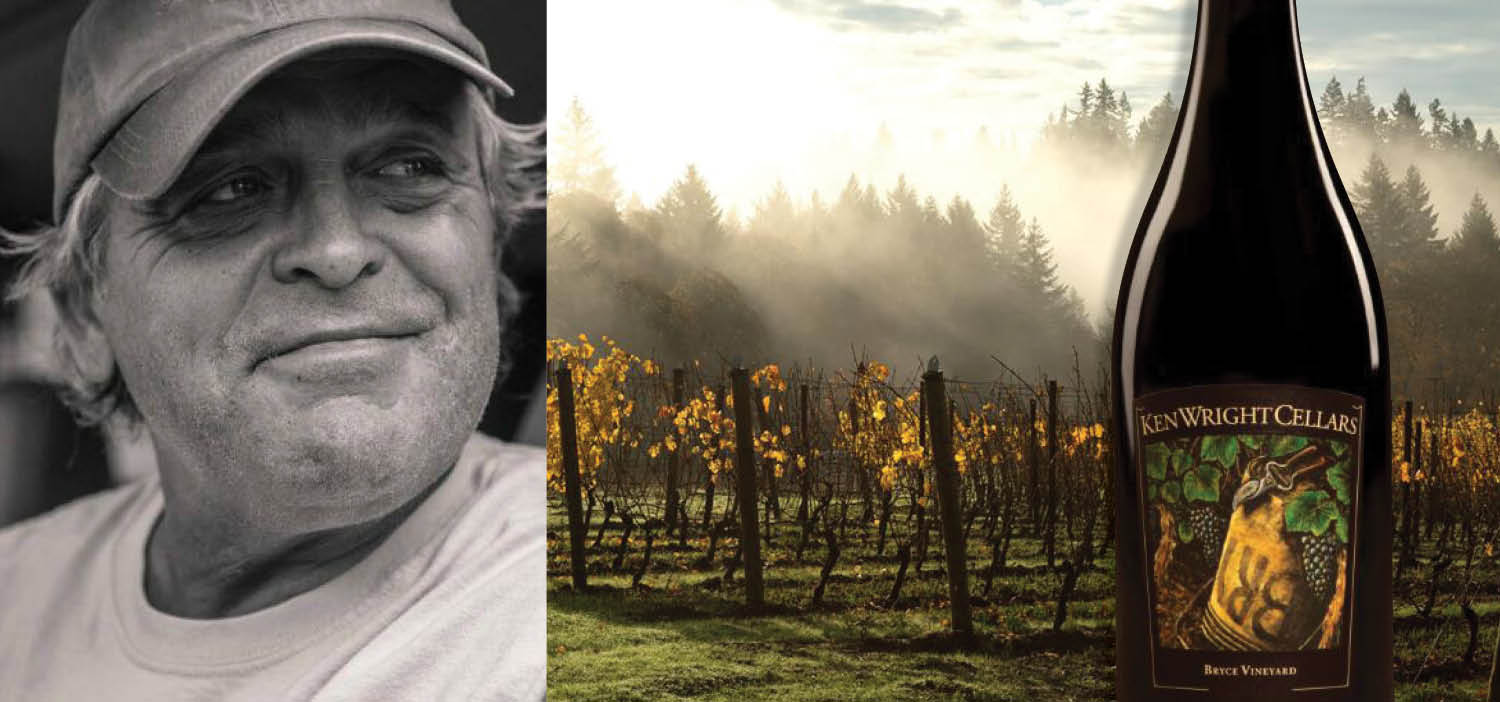

(Photo: Ken Wright's vineyards in Willamette Valley, Oregon)

I moved up to Oregon in '86 with 10 barrels until I, actually, in '85, Martin Ray had.. do you know who Martin Ray was? Martin Ray was a figure. A figure of importance in California, let me tell you. He really was the one who brought the industry to it's knees and embarrassed the industry regarding the fact that at the time the law was that you only had to be 51% varietal. So you could make Cabernet Sauvignon, you could make Pinot Noir, and it only had to be 51%. You didn't have to tell anybody what the rest of it was. And it embarrassed him that the standards were so low, but also, at that time the industry in California, California was the black eye of the world, because they were using labels, like Chablis, like Burgundy, and more, with champagne to sell wine on the backs of others. The rest of the world saw California as a substandard place as a result. Martin Ray was the one who really called people on the carpet, the whole industry, and said, "This is not okay. If we don't believe in ourselves more than this, we're never going to be a region of note." Funny how, he was important, and for some reason, people don't seem to remember that.

He's amazing. So, yes Martin has passed and his wife, Eleanor, I'd known her for years because they're situated right next to Mount Eden, right next to where we were holding our meetings. She contacted me to say she had this fruit, this beautiful, old vineyard on their property that she didn't have a home for.

So in 1985 I took that fruit, which was a combination of Cabernet and Merlot. Very small, but very beautiful, small vineyard. It only produced 10 barrels of wine, essentially. And that was the wine that I brought to Oregon with me in '86 when I started my business up here. It was a bit weird to bring a Bordeaux blend to the heart of the Willamette Valley, but I did. It was a very, very good wine, eventually.

I was going to say, when I brought it up, I was so naive about the laws regarding alcohol, generally, that I brought that up in the truck that had all my belongings. And the barrels were just trapped in the case of a trailer and I set up shop in McMinnville, Oregon. At that time, there wasn't the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, the BHES, which still ruled us at that point, before 9/11, the BHES, they would send agents out, and you don't see that happening anymore. But they would actually send an agent out to inspect you, to make sure that you were real. And they would meet with you and interview you. The agent that came out for me, his name was Ron Fitzgerald, he came out and he was sitting in my crummy little office. I rented this space for $250 a month, and he was sitting there with me, and just kept going through the checklist. He goes, "I can see you have a stemmer, I see you have some tanks, you have your pumps, and I can see you've got some barrels in the back there."

And I said to him, "Yeah, that's amazing wine from the Santa Cruz Mountains that I brought up with me when I moved up here." And he said, "What?", and I said, "Yeah! It's terrific, terrific fruit from Santa Cruz Mountains." And he said, "You're not licensed to produce yet. You can't have that wine, yet." And I said to him, "If I can't sell that wine, I'm out of business before I start." And he realized that I was just incredibly naïve and that I wasn't trying to circumvent any laws. And he took pity on me and he found a way, writing letters to people throughout the chain of command, he found a way for me to able to sell that wine. Which was huge. At the time it was just absolutely huge. So I thanked him, will always thank him for that, for working on my behalf.

So that was the first wine we had. And of course the focus was Pinot Noir. The reason I came to Oregon was Pinot Noir.  What brought me here was, I had been visiting the area for years, that same fellow that I was roommates with back in Lexington, came to Oregon State to get his doctorate. And he became the vineyard manager for what was then called Knudsen Erath. I'd visit him quite a bit and over all the years when he would visit Buckley I would visit him here. I became familiar with Pinot Noir from that area, and enamored with it. Just absolutely loved the profile of the wine. And I remember at that time, there was a lot of inconsistency for a lot of different reasons, but when they were on the mark, they were absolutely beautiful. That's what drew me up here.

What brought me here was, I had been visiting the area for years, that same fellow that I was roommates with back in Lexington, came to Oregon State to get his doctorate. And he became the vineyard manager for what was then called Knudsen Erath. I'd visit him quite a bit and over all the years when he would visit Buckley I would visit him here. I became familiar with Pinot Noir from that area, and enamored with it. Just absolutely loved the profile of the wine. And I remember at that time, there was a lot of inconsistency for a lot of different reasons, but when they were on the mark, they were absolutely beautiful. That's what drew me up here.

(Photo: Pinot Noir grapes on the vine)

Do you want to tell us about your philosophy of viticulture and winemaking, now that you're an established and successful winemaker?

In the end really great success is when you have the right variety in the right location, where it inherently wants to be magical. For me, it applies to all things, all plants around the world. If you think of the great things that we have in terms in food, particularly, it's always about environment.

If you love tomatoes and, you know, San Marzano tomatoes are absolutely the ultimate experience in Italy. And it's not because someone in Italy is a genius, it's because that plant loves that place, absolutely loves that place. All the environment factors there, everything, all of the influences are exactly the right thing for that plant.

I go to Japan every year. Every April, late April, I go to Japan, have for a dozen years, and I don't go there at that time for the Cherry Blossom Festival, although the cherry blossoms are out, it's really more for the bamboo shoot in Kyoto. Bamboo shoot, generally, at least when I grew up in the Midwest, bamboo shoot was something that came in a can and tasted like sawdust, but in Kyoto, it's absolutely a religious experience. It's the most amazing, amazing plant and when prepared correctly, it's insanely delicious. And so, I've been everywhere around Japan, nowhere else in Japan is it that good. People make a sabbatical to Kyoto from all over that country to have the bamboo shoot at that perfect time in late April. And that's because all the conditions are right. It's exactly where that plant wants to be amazing.

And that's what we have here in Oregon. The Willamette Valley is a very, very broad, it's a massive area. The reality is 95% of it is not suitable for quality fruit, but the the sub-AVAs that I was involved with in creating here years ago I wrote one of them, I was the author of one, the sub-AVAs are really there to identify those areas in the valley that are absolutely world class.

And to create essentially, a roadmap for those coming to our region about where they should plant, where they would be likely to have the greatest success. Because we didn't need people coming to the region planting in inferior areas and making poor wine. That doesn't help anybody, certainly doesn't help us. We need everybody working at the highest possible level. As a small region, it's all about quality. It's all about that. So we had to identify those small areas.

So these areas are places where this plant, or Pinot Noir, wants to be spectacular. It inherently wants to be amazing. It's been on us over these last 50 years. So we learn how to farm, in a way, how do you farm in a way that supports this plant at the highest levels? It can realize all of the potential it has. And that takes time. Farming is hard, and it takes years to understand your individual properties and what you need to do to support that plant in an ideal way. And in the end, it's always about nutritional balance.

Do you think your winemaking has evolved over that period of time working with your vineyards?

Yeah, I mean, we were the first sorting in Oregon. We were the first to create a sorting line, the first to use dry ice. Back in the day, one of the issues we had here in Oregon was that the way business was done, and this is California as well, the way business was done, you were buying fruit by the ton, okay? You didn't necessarily have your own blocks to work with. You would simply work with a grower, they would do their best to accommodate your order for fruit from wherever they could in their vineyard. That's the way it was. At that time, there was no mechanism between a purchaser and a grower, there was no mechanism to do thinning. If you're paying the grower by the ton, you can't go to them and say, "Hey, would you mind dropping off the crop so we can make something more concentrated here."

So years where you had all the accumulated heat you needed to ripen before the weather broke down, everything worked out. But there were too many years where it didn't, where you had a cooler season, there wasn't enough accumulated heat to get the fruit in the barn dry before the rains would come.

And essentially, in Oregon, the way it works is you have, while we're getting into harvest, we're also looking north to the jet stream, which starts up in Canada and it begins to slowly fall down south, coming through Washington State and eventually, normally right at mid-October, it begins bringing in, from the Pacific, one storm after another. If you're not done, if you're not in the house with all of your fruit before that begins, you're going to struggle. You're going to have pollution from rainfall, you're going to have disease. Disease begins almost instantly. You're going to struggle.

And essentially, in Oregon, the way it works is you have, while we're getting into harvest, we're also looking north to the jet stream, which starts up in Canada and it begins to slowly fall down south, coming through Washington State and eventually, normally right at mid-October, it begins bringing in, from the Pacific, one storm after another. If you're not done, if you're not in the house with all of your fruit before that begins, you're going to struggle. You're going to have pollution from rainfall, you're going to have disease. Disease begins almost instantly. You're going to struggle.

(Photo: Harvesting grapes at Ken Wright Cellars)

So that is the key. In a quiet year, the way in which you can alter the dynamic is to remove crop, it's serious sacrifice, but you can remove crop to lessen the workload of the plant. The engine of the plant is the same, the leaf surface is your engine, so that's your photosynthetic engine. It remains the same, year in, year out, essentially. You're working with the same canopy, the same leaf surface. But the weight of what you're asking that engine to push through a season, the weight can vary dramatically, very dramatically, from year to year.

In a cold year, the way that you can get home before the fall rain begins, is to lessen that work load, which we did. Which is what we do now. We began that in '87 by changing the dynamic. We looked at our growers and said, "You know, given the conditions here, we can't be good in most years. We have to be competitive and producing the wines that are compelling every year. We're not going to get there with this current arrangement of buying by the ton. We have to change the dynamic."

So we were the first to do that. In 1987, we went to our growers and said, "We want to buy by the acre. We want to do acreage contract where we are paying you a set fee for an acre. And those vines are now our vines. Those blocks are our blocks. And if we determine during the year that we need to drop crop at any level, you need to be contractually obligated to do it for us to be successful because you're collecting the same check."

The grower doesn't care anymore, right? They're getting paid and that time it is was $5,000 an acre. We said, "Well, you're getting the same check no matter how much fruit we take, so you're no longer impacted, but we need a different way of doing business." And that was a huge thing. That was a big change for us and then eventually for everybody. And that's the way that business is generally done universally at the highest levels, obviously. So that was a very big deal.

For me, the connection that Pinot Noir creates to us, that connection to place that it provides, I don't think is matched by anything else we consume. I can't think of any food, any other beverage that begins to connect us to place in such a complex way. We work for the wine varieties, how they have a varietal makeup that includes traits that can dominate place at some level.  For me, Pinot Noir is a completely blank canvas and everything you smell and taste has everything to do with where it's grown. Everything. So that, when it's done right and you're farming correctly, and of course there's the absolute assumption that you have that variety in exactly the right place, that when you support it correctly through your farming and you get a huge voice coming because of that correct support, it's amazing.

For me, Pinot Noir is a completely blank canvas and everything you smell and taste has everything to do with where it's grown. Everything. So that, when it's done right and you're farming correctly, and of course there's the absolute assumption that you have that variety in exactly the right place, that when you support it correctly through your farming and you get a huge voice coming because of that correct support, it's amazing.

(Photo: Pinot Noir grapes)

To me, it's in our correct place as human beings and so many people talk about their winemaking approach and this and that, and to me, that's all good, but the gift that this plant brings to us, it's a serious gift. It is beyond us. We need to learn how to support it, but what's magical is that it's something beyond. The reality is we're just learning how to be fake stewards and making the right choices for supporting the gift which is this possibility to do what it does and bring pleasure to us. For me, Pinot Noir is the ultimate. It's absolutely the ultimate in that ability.

What are your thoughts on organic viticulture?

Organic is, what we do, we meet the standard in our approach, but you have to understand, minor organic or biodynamic requires testing to show nutritional balance, okay? I applaud anybody that wants to farm in a sensitive way, but in the end, what really matters is that you have to go beyond that. Organic is really just a list of chemicals you can't use, that's all it is. It's of a list of chemistry you cannot use, but there's no requirement by that farming method to investigate your site, to actually investigate your property, to do the testing that tells you in real language and hard facts what's really going on.

It means, are you deficient in manganese? Are you excessive in phosphorus? Are you in perfect shape with copper, iron, zinc? You don't know. The problem is, for me, if you don't know that stuff further, if you don't go the step further to really understand what's going on in your place, then you're farming in a blind fashion. It's just a recipe. And you know, the same recipe doesn't work at 5,000 feet as it does at sea level. And if you're not addressing the actual nutritional needs of your site, if you're not actually down there at next level, then you're just guessing. You're just hoping that you hit the mark. And you might. You might do just fine, but it won't be through knowledge, it'll just be through a recipe, thinking that it will work.

So for us, this started, oh let's see, it's really based on Japanese farming, beginning about 25 years ago. It was funny because in serious farming, I mean when you talked about serious farming operations, not grapes, but anything, those folks who do serious farming, they understand exactly what's going on in the properties to the square inch. To the square inch, they know what the nutritional needs of their properties are.

And in our own business, it's so funny, we end up with these romanticized kinds of approaches that have no, necessarily, basis and fact of any kind. I find it, I mean, I like to know what's going on. I want to know, I don't want to guess that I might be doing the right thing. I want to know what. I think that if you do that, I know that when you do that, you can see, it's amazing to see the change that happens in the vineyard.

And in our own business, it's so funny, we end up with these romanticized kinds of approaches that have no, necessarily, basis and fact of any kind. I find it, I mean, I like to know what's going on. I want to know, I don't want to guess that I might be doing the right thing. I want to know what. I think that if you do that, I know that when you do that, you can see, it's amazing to see the change that happens in the vineyard.

(Photo: Checking seed development)

For us, it's more about, in the end, when you talk about winemaking style, I try not to think I have a winemaking style. I'd like to think that we have learned how to farm in a way that we are getting a wonderful volume to aroma and flavor to the right kind of nutritional support where the plant is really just humming. Then learning how to be invisible. Honestly, if what we're trying to do is showcase place, which is what we, we've been doing this longer than anybody in Oregon, big, single vineyard wines, by far, we're the only ones for years. And that's because we love that. We love the ability to get connected to place. We think it's a magical thing the plant provides. In order to do that, to really showcase place, you need to become invisible. It's much harder to be invisible than it sounds. It's easy to be manipulative. It's really hard to protect and enhance the fruit. That's hard. It's really hard. It starts, always, with farming. Always. No one in the world is that good where they could take average fruit and make it extremely wonderful. That doesn't happen.

Do you want to talk a little bit more on the terroir of your estate and your different vineyards? I know you've touched before on climate and soil.

So, to understand the valley, it's pretty simple in the Willamette Valley, fortunately. Our region was created by plate activity years ago from the scrapings. Where we exist, here, this was all Pacific Ocean. I mean 200 million years ago the state of Washington did not exist. Nor did half of Oregon. At that time, the Pacific coastline was way further east and over this couple hundred million years, we've had the Juan de Fuca plate, which is our nearby marine plate, plunging under our coastline. As it plunges, the soft sediments that are on the top of that plate get scraped off as it rubs against our coastline, then plunges downward and under the crust. All of Washington and half of Oregon were created in this manner, so all of the base material for where I am now, and in Washington, all of Washington State is made of sediments. It's all sand. All of it. So that's how it was initially created.

Just 15 million years ago, just like yesterday, 15 million years ago there was a set of volcanoes on the other side of our state near Idaho, on the eastern side of our state.  They're called the Blue Mountains now, but back in the day, 15 million years ago, they were the most violent chain of volcanoes on the planet. Over a very long period of time, they issued so much lava that it's called the Columbia River Basalt flow. It's the largest flow of basalt in the world. Any geologist could tell you that.

They're called the Blue Mountains now, but back in the day, 15 million years ago, they were the most violent chain of volcanoes on the planet. Over a very long period of time, they issued so much lava that it's called the Columbia River Basalt flow. It's the largest flow of basalt in the world. Any geologist could tell you that.

(Photo: Columbia River Basalt flow)

It issued so much lava that it came all the way west across the entire state, including where we are here in the valley. It created a veneer, or a laminate, over the valley, over those marine sediments that were here first from the plate activity. So it's a veneer, you know, a couple hundred to three or four hundred feet over the marine sediments.

That's 15 million years ago. Since then, it's been pretty quiet, geologically. So that veneer, that covering over the marine sediments has been eroding and weathering and going away. So now, as of today, there are islands that are left of that topical basalt, of that volcanic flow. Those are places you may know, like the Dundee Hills. The Dundee Hills is a remnant, a vestige, of that flow that came from the other side of the state 15 million years ago.

The Eola Hills, same thing. It's a remnant of a flood. These are volcanic areas. They're not volcanic from activity underneath, there never has been, ever. Ever. It's just what's left of this incredible flood that came so many millions of years ago. Around them, the marine sediments are now re-exposed, the really old stuff now has been re-exposed. What we see is that the new plant, Pinot Noir, in the volcanics, in the young stuff, planting in the volcanics, the wines will tend to be fruit driven.

So, Dundee tends to be more of a red profile, you get cherry, strawberry, raspberry. Eola tends to be much darker in its profile. You're seeing blueberry, black cherry, cassis. The McMinnville area is also volcanic, it's similar blue, black in profile. While the type of fruit might vary from place to place, the seam remains the same. The seam is that the volcanics tend to be more fruit driven wine.

When you plant Pinot Noir in the marine sediments, the old stuff, it's totally different. It's a different creature altogether. It becomes very savory. You're going to see chocolate, cedar, tobacco, clove, root beer. All of these elements that are not fruit driven. And it's just because that's what it's about, the mother rock. It's not about soil, never about soil, it's always about the mother rock. It's the mineral make-up of that mother rock that is driving that profile.

People talk about soil so much, it just blows my mind. I don't get it, because when you plant vines, you know, in those early years when your root system is fairly shallow, it's only exploring soil, you have very little character. Really, the wines are part muddled. They lack clarity, they lack specificity, they're just whatever, muddled. It isn't until your vines are old enough that the root system is beyond soil and engaging your mother rock. And, assuming that you're farming correctly and that you have the microbiology present to break it down, to break that mother rock down, that's when the change happens.

That's when all of the sudden, the site goes from being okay to being incredibly detailed. All of a sudden you see all these qualities that weren't there before, once your root system is in that parent material. And that's what you wait for. As a grower and as a winemaker, you're waiting for that important time where the vineyard is at an age where that begins to happen, because all of a sudden you have a whole new set of characteristics that make that wine so interesting.

To understand the region is to know. Anybody drinking Oregon wine, their first question should be, every time, at least the Willamette Valley, the first question should be, "Is this volcanic or is this sedimentary?" Because if you do that, if you begin caring about that, you will begin to see a pattern. And you may not describe it like I do, people are different in the way they do things, but you will see a pattern, I promise you that. You will begin to notice the characteristics of the volcanics are definitely, completely different than the sedimentary sites. And it's all eye of the beholder. There's no right or wrong. It's whatever pleases you, in the end. There's a lot of people who much prefer the marine sediments, they like those savory qualities. Tons of other people do not. They prefer the more laser-like fruit. There is no right or wrong, it's just what it is and in the end, it's this wonderful ability to be connected, again, to place, by this plant.

So, how would you say Oregon has evolved over time as winemaking region?

Well, a lot over the years. We had the benefit of having a region that innately, this plant, wants to be great here. It really does. And again, all success comes from that.

But over the years we've learned about, inherently, the trellising methods that work and don't work here, cloning material. We were so lucky, honestly, we were so lucky that David Lett brought Wädenswil. It was '66, not '65, like the books say, it was '66. David Lett brought Wädenswil in '66, Dick Erath brought Pommard in '68. Those two clones really provided the basis for some amazing early success that happened from this area.

But over the years we've learned about, inherently, the trellising methods that work and don't work here, cloning material. We were so lucky, honestly, we were so lucky that David Lett brought Wädenswil. It was '66, not '65, like the books say, it was '66. David Lett brought Wädenswil in '66, Dick Erath brought Pommard in '68. Those two clones really provided the basis for some amazing early success that happened from this area.

(Photo: Vineyard at Ken Wright Cellars)

And that's because those two clones were so well matched to this region. One is, the Pommard is the basso. It's more tannic, darker colored, more muscular. Whereas the Wädenswil is the soprano, big time. It's all high notes. It's not necessarily darkly colored, it's not tannic, but it is absolutely beautiful and ethereal and complex. Together, those plants were super well matched, because they provided such stretch to the aromatic and flavor profile. Beautifully matched.

Many plants came and went over the years, but some kind of worked, some didn't work at all. Eventually the design material came from Raymond Bernard in the '80s from the University of Dijon. Oregon was the first area outside of France to get the Dijon material, because Raymond loved Oregon so much. Those had become clones as well. So cloning material can make a difference.

Having the acreage contracts that I mentioned, changing our way of doing business so we could control crop level is key, really key.

And then things like, we have, when it comes to thinning, used to be that lore, when I was in California and when I first came up here, there was this lore and assumption, our world was full of it, that you should never thin before color. That if you did, if you thinned before color change in the fruit, that the fruit would size up. You'd have a very large berry size. Which would mean less skin to juice, meaning less color, less flavor, less all that. And that was the lore. I've been working with a group, we call ourselves the Cellar Crawl, we've been working together for 23 years now, doing experimental work here in Oregon.

One of the things we took on was this lore and assumption about thinning. So we did a trial for many years, that everybody participated in. There were six of us, six brands. We proved that it does not exist here. There is no sizing. What it meant is this: if you wait 'til color to remove fruit, for thinning, you're only six weeks from harvest. Essentially, you really haven't done anything to help yourself. We found that we could thin as soon as right after flowering in June. So we could be thinning by mid-June, which means you're taking away, to really make a difference in that plant's ability to ripen that fruit sooner in a cold year, by thinning that early, you've removed all that weight. All that weight from the plant months before you thought it was okay, traditionally. And it makes a magnificent difference. And it is huge in terms of granting the plant lightness when needed. With that thinning, that changed everything. People now understand they can thin much earlier.

We have tighter spacing than we used to have, which I think can be helpful. In the end, older vines, you really treasure older vines and even widely-spaced older vines can make unbelievably great wine, but there are advantages to tighter spacing, especially in a cooler year because you have more leaf surface in a given acre of ground. Your engine is just bigger. It's a bigger engine and so you can help yourself in that case. It's more expensive to be more closely spaced. It's more expensive over the year, 'cause your farming costs go way up, but it can be an advantage in a challenging year, to have more leaf surface, for sure.

We started dry ice use, came in about 1994, which made a difference.

I think we've done a lot of work, these studies and so on and so forth that have changed, it really changed things over the years. People's approaches.

We were the first to do salting of barrels. Back in the '70s and the '80s, barrels were pretty consistent and they were essentially as advertised when you purchased barrels and you asked for a certain amount of AOs of aging of the wood, seasoning, and source based on forest, etc, etc. The pressure on wood supply, because of the growth worldwide, it's insane.

We were the first to do salting of barrels. Back in the '70s and the '80s, barrels were pretty consistent and they were essentially as advertised when you purchased barrels and you asked for a certain amount of AOs of aging of the wood, seasoning, and source based on forest, etc, etc. The pressure on wood supply, because of the growth worldwide, it's insane.

(Photo: Barrel room at Ken Wright Cellars)

When I left California, there was not a vine, Sonoma Coast didn't exist. There was one winery in Santa Barbara. It was a very different world. And it's amazing worldwide the change that's happened. Look at South America. South America wasn't in the game back then, quality-wise. The growth in Australia and the rise and quality of line from Italy, I mean, back in the day, you had Gaja making some good wine, but my god, there was a lot of bad wine coming out of Italy.

That has all changed. That has all changed here in the last 30 years. It's amazing, worldwide, how the quality of wine worldwide is amazing and the use of oak is part of that. So the demand on oak is crazy, in fact, I was sitting here, I had a visit from André Porcheret and Denis Mortet, when he was still alive, they were visiting with me here in Carlton.

André Porcheret was the winemaker at the Hospices de Beaune for 35 years. And of course Denis has his own label in Burgundy. We sat there, were sitting in '94, I think it was, and we just noticed that the barrels supplied by French coopers were becoming almost inconsistent. There was a lot of green wood. A lot of cheating going on, frankly. A lot of cheating because of demand.

And I was using this steaming method trying to get rid of the harshest resins and so forth, and I asked them, "Have you noticed this trend that barrels are becoming so inconsistent?" And they said, "Oh yeah, absolutely" And I ask them what they were doing, and André, next to me, he was having a lot of success with this salting technique of using cane-dried salt to extract the harsh resins from green wood. Anyhow, we started doing that. So we were the first to do that in the U.S. back at that time, but yeah that's become kind of standard operating procedure for most to do this practice to eliminate this issue. But that's a detail.

I think in the end, we've all gotten, as an industry, we've gotten more and more focused on the farming side of things and understand how critical that is. Increasing the quality of the fruit you receive so that you have the best chance of making something beautiful. We've become better and better at protecting the wines through the process of winemaking. It's really, it's been so interesting.

I remember I was in China a couple years ago and traveling there for the first time and I was absolutely shocked at the awareness of the Chinese wine industry, one with people involved there, in the restaurant industry especially. I was amazed of the awareness of the Willamette Valley. I mean, I thought I would go there having to teach, point to a map and say this is where Oregon is and this is where we are. It was not like that at all. It was actually stunning how well, not only did they know the Willamette Valley, they knew how to say it, and then they would give me two thumbs up and say, "Pinot Noir." And that really hit home for me during that trip what a wonderful and significant asset we have, that we have this association of Willamette Valley and Pinot Noir. Not every region has that.

I mean I would suggest only Napa Valley Cabernet and Willamette Valley Pinots have that in the U.S. And so, it just struck me that we now really have a worldwide, truly a worldwide asset that took the work of a lot of great people. A lot of great people through this history here, 50 plus years, have done so much to create what we have. And it's really because we were so fortunate that people who came to this area were so passionate and were driven, truly driven, by making the very best wine they could possibly make. That has been the trend. There were enough folks that came first in filing, had tended to be incredible collegial and sharing people. Somebody needed a cup of sugar, they all got a cup of sugar.

It's been an incredibly sharing industry and an industry that cares about each other and each other's successes. We all know that we're small fish in this pond and in the end, as I said, it's all about quality. Making some amazing wine that's going to be on the world's stage, 'cause we're certainly not ever going to be it by volume. That's for sure.

Obviously Pinot Noir and Oregon go hand in hand, but are they any other grapes that you're excited about growing in Willamette Valley or want to experiment with?

Chardonnay is increasing now. In the beginning, most of the Chardonnay that was in the Willamette Valley was the UCB 108 and it was a perfect tone for Chardonnay.  It did well. It did well in a number of areas in California, but it did not do well here. For me, it is something that still hasn't, not producing wine so much, but for me, I found it difficult.

It did well. It did well in a number of areas in California, but it did not do well here. For me, it is something that still hasn't, not producing wine so much, but for me, I found it difficult.

(Photo: Ken Wright's Savoya Chardonnay)

It wasn't until in the '80s and actually pushing into the late '80s that we were able to receive the new cloning material from Raymond Bernard. So we got four clones at that time that have all done pretty well, but again, they were young and we just got them, most of it came in the late '80s. Those vines got planted, but you're not going to see, as I mentioned, you're not going to see, until the vines are deeply rooted, you're going to begin to see the real, the true complexity of what they can do, for years. It's years and so now, I think in the last, especially the last I'd say eight years or so, a lot of those vineyards that were planted are now at an age where they're really producing some really good wine. Really good wine.

There are lot of people producing some Chardonnays that are absolutely beautiful. And really detailed, really pretty wines. So that's great to see. We weren't as lucky with Chardonnay as we were with Pinot Noir in terms of what was brought first, so that took a generation to turn the other direction. I'm tasting some delicious Chardonnays from around the region now that I think are really compelling, really beautiful wines. We make a very small amount ourselves, you know, from the 548 clone which is a clone we brought in 2001 that we think is making some terrific wine.

There are other varieties I think that can do pretty well. There are some Pinot Blancs from the region that are quite pretty. I think when it comes to part of our world, there are realities of having to make ends meet. Every acre that we dedicate to something other than Pinot Noir is generally going to be a less profitable acre of ground. It's just a fact. So the other varieties tend to become, just because of economics, they tend to become hobbies. You do it because you love it, but you don't do so much that it becomes difficult.

Home page banner art by Piers Parlett