In 1991 Frank Prial writing in the New York Times described Hudson Valley wines as a little eccentric. "Some are, at best, idiosyncratic and really out of the mainstream of New York or, for that matter, American wine making." Today though the region has moved forward in leaps and bounds, it is still playing catch-up to New York's two most popular wine regions, the Finger Lakes and Long Island.

While French Huguenots planted the region's first vines in 1677 the area is still better known for apples than grapes. However, today there are a dedicated group of winemakers who are focused on quality and on elevating the reputation of the region and one sees the Hudson Valley popping up on the wine lists of top New York City restaurants with greater frequency.

I first encountered Whitecliff Vineyards on the venerable wine list of Gramercy Tavern. I was surprised to see a Hudson Valley wine on the list and even more surprised at its quality when I tasted the wine. The winery was established in 1979 and has through continued trial and error become one of the shining examples of the potential of the Hudson Valley. They currently work with about 20 different grapes.

Grape Collective talks to Whitecliff owners Michael and Yancey Migliore about their Hudson Valley wine journey.

Christopher Barnes: Talk a little bit about the estate here. When did you start?

Christopher Barnes: Talk a little bit about the estate here. When did you start?

Michael Migliore(MM): So this land I've been farming since 1975, back when I was a graduate student at New Paltz University and it started out, not as grapes in '75, it started out as raising dairy cattle replacements and growing hay, and then when I graduated from New Paltz as a graduate student, I was an undergrad-

Yancey Migliore (YM): In chemistry.

MM: In chemistry, yes. I got a job. I got a job with IBM. So at that point, it was, okay, I have some money, I'm gonna buy a piece of the property. I would choose which piece I wanted and chose this hilltop 'cause I knew a little bit about grape growing because I spent my summers in the Finger Lakes with my grandfather at my aunt's farm. So she was a corn and wheat producer up there, but my grandfather was from Miltenberg in Germany and we would go visit Finger Lakes wineries. That was what we did in the summertime. So I had a knowledge of grape growing in the Finger Lakes.

And then I acquired the property in 1978 and immediately planted some grapes. Planted a few hybrid varieties. They did well on the hilltop here and then, when Yancy and I were married in '83, we started this vineyard here, which is about 1.5 acres. And almost every row is a different variety. We spent really 10 years experimenting and seeing what would grow well and what wouldn't. And then in about '93, planted the two acres in the back. We have 18 acres on this plot. And then in '95, acquired 52 acres adjacent to us.

We actually purchased it from the Jehovah Witnesses. It's a very interesting process. We took the whole family over there. We were interviewed. Somebody became our advocate to go before the board in Brooklyn. Pitch our cases that farmers won't expand. They agreed. We agreed on a price. And we acquired then 52 acres. Now we're at 70 acres.

So '96, we start planting out the other side there. We had determined at that point that it's mostly the Bordeaux varieties were okay, but the Burgundy varieties did very well, and south of Burgundy. So we determined to be planing Gamay Noir, we planted Chardonnay, we planted-

So '96, we start planting out the other side there. We had determined at that point that it's mostly the Bordeaux varieties were okay, but the Burgundy varieties did very well, and south of Burgundy. So we determined to be planing Gamay Noir, we planted Chardonnay, we planted-

YM: Some Pinot. On our best spot, highest.

MM: On our best spot on the hillside, and so then marched on at five-acre parcels at a time. And sort of is still working through this and planting. So my heritage, both grandfathers were home winemakers, and this is what I know and it's my background and this is what I want to do.

And how many acres do you have right now planted with vines up here?

MM: On this site right here, we have 26. We have two other vineyards. We have a wonderful hillside vineyard on the Hudson River, north of Newburgh in Middle Hope, which is on calcareous soil. So we have Pinot and we have Chardonnay on that site.

And then we have just planted a new vineyard three years ago, which is in Hudson, New York, just the other side of the RIP Van Winkle Bridge, and that is six acres of Pinot Noir, Gamay Noir and Cabernet Franc.

YM: Which are really I think the best red grape varieties for the Hudson Valley, and even beyond. I mean, Cab Franc is now taking over, I think, in New York red production.

MM: We had been involved in a vineyard project south of where we put on our new vineyard. It's on this ridge that's right over the Hudson River, runs right down to the water's edge, and we had been involved in the production of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir and Riesling there. So I knew this site. So it was just another thousand feet to the other side of the ridge, and when it was offered to me as President of the Hudson Valley Wine and Grape Association, somebody approached me, "Do you know anybody that would be interested in planting grapes here?" It was so fortuitous, I said, "Yes, me." I know this ridge, I know I wanted to do that.

So it was a long process, we didn't buy the land. We're leasing it on a 25-year lease and there were four siblings and the matriarch of the family and negotiating all of this because they had never leased land before, so it took a good year with a lot of effort and a lot of times saying, "What are we doing? Let's just walk away from this." We would think we would have a contract, another sibling would pop up, we would have to redo the whole thing. I signed agreements and leases all the time. They're usually one or two-page agreements. This agreement wound up being 26 pages long.

But it was done. And we all did this elaborate dance around each other, looking to see if we would trust each other. And low and behold, we really like each other. So I feel part of the family. They feel really part of the grape-growing experience. So much so that I've hired the son of the matriarch and he works for me, doing everything from spraying and mowing and shoot positioning and leaf pulling and everything else.

But it was done. And we all did this elaborate dance around each other, looking to see if we would trust each other. And low and behold, we really like each other. So I feel part of the family. They feel really part of the grape-growing experience. So much so that I've hired the son of the matriarch and he works for me, doing everything from spraying and mowing and shoot positioning and leaf pulling and everything else.

So for me, it was a great thing, because it's an hour and 15 minutes away. So if I load up my crew in my truck and go up there, I'm paying for two and a half hours of just sitting in the truck and watching the road go by. So if I can get labor and skill up there, it's just a great thing.

So a total, where you asked how many acres are we actually farming right now, we're farming 35 acres and we're looking at now expanding that. We need to put in some more varieties here on our home site and as I talked about before, there are 120 acres at this site up in Hudson that's available to me and I may put in some other varieties there.

Certainly the demand is there in the Hudson Valley. Hudson Valley produces in the region of a thousand acres of grapes, from Long Island and the Finger Lakes. I have a long list of fellow winemakers who want to purchase my grapes. We were just agonizing over that today. I promised somebody a ton of Cabernet Franc. I'm trying to figure out how-

YM: Which fruit to give him.

MM: How I'm gonna get that to him.

Talk a little bit about the terroir in the Hudson Valley.

Talk a little bit about the terroir in the Hudson Valley.

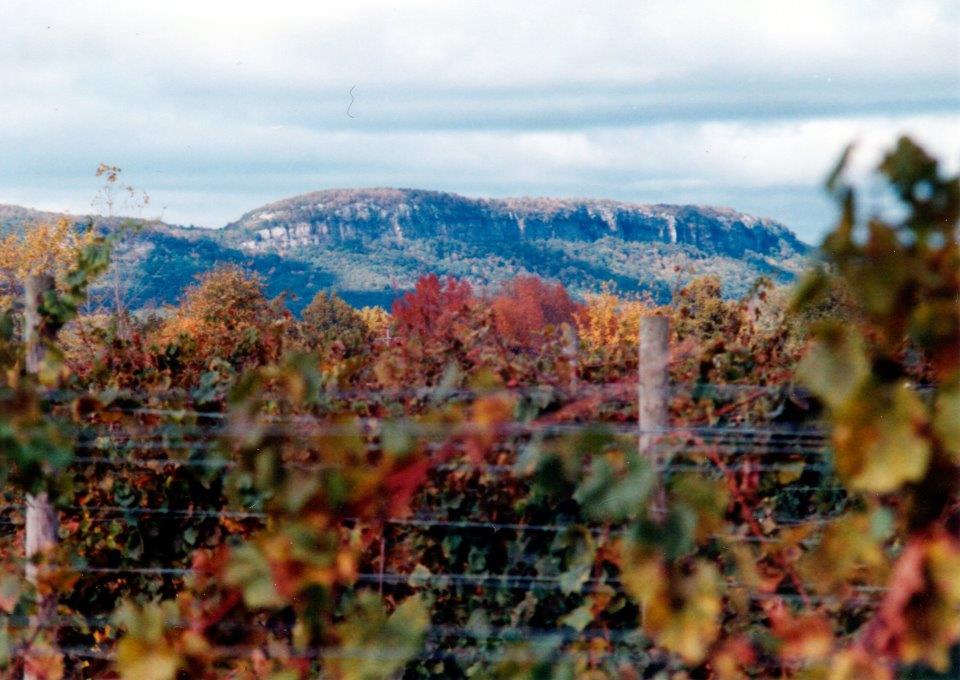

MM: I'm going to reach down and I'm gonna pick up a couple of rocks here from this site. So this site here you're looking at quartz conglomerate. You'll see the cliffs in back of us later. So here's two examples of the terroir of this soil site. So all of this was formed by the Wisconsin Glacier 10,000 years ago. So it brought material from other mountain ranges. Catskills brought down this sandstone and shale stone. Quartz conglomerate was formed 400,000 years ago. There was an inland sea. The shoreline was right along the edge here. This sand was part of that shoreline. Three mountain ranges later, compressed this into a hard material, and then differential erosion of shale formed the cliffs that are in back of me to form. So we have quartz conglomerate, sandstone, and shale in a mixture of glacial till, which is medium in terms of organic matter and medium in terms of the amount of clay.

So you'll see that throughout my site, but there are three different soil types here. There is Castile, there's Cayuga, and there's Churchville. So this goes back to having a knowledge of viticulture, planting the right grape with the right root stalk on the site to have it survive.

What about the climate here? I mean, you know, it can get quite cold here in the winter.

MM: So the climate here in the winter used to be quite severe. You would see routine winter temperatures of two years in 10 that would be less than 16 below zero. So magic numbers if you're looking at grape varieties, viniferous varieties, Riesling, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, are cold hearty to eight, nine degrees below zero, depending on how it hardens off going into the fall. And the hybrid varieties, which we also grow, are usually good to around 16 below zero.

So for the first 10 years after we planted, from the '80s into the '90s, we had a lot of severe winters. What we would get is that the trunks would die back to the ground and you see these are moderately hilled up, so anything that has a grafted root stalk, we would hill up with dirt over the wintertime to protect them. What that would mean is, yes, maybe we would lose the upper part of the plant, but we would not lose the whole plant and have to replant it. So we could bring up a new trunk. Maybe we've lost the next year's production, but we don't have to replant.

That's changed. That's really changed. You may deny climate change, but it's happening here. So now over the past three or four years, we see low winter temperatures, instead of 16 below, we see them three below, and what that means is all of the vinifera will survive without trunk renewal. It's a massive change. I would not change that for the sake of my production versus the planet, but it's a reality for what we're doing here.

YM: We also still get wild swings of temperatures so, even though the typical low is much warmer than it used to be, we'll get, you know, one night where it swings way down, so we've been very mindful of which varieties we plant on a flat as opposed to with a hillside where you'll have several degrees of more moderate temperature. We invested in a wind machine, which can save you several degrees on the coldest night. You know, for us now, it's about the dangers of a few hours on one or two nights. At four in the morning, when everybody else is in bed, do we turn on the wind machine, which sounds like a helicopter landing in the middle of the field, in the middle of the night? But yes, we still give it all a lot of thought.

YM: We also still get wild swings of temperatures so, even though the typical low is much warmer than it used to be, we'll get, you know, one night where it swings way down, so we've been very mindful of which varieties we plant on a flat as opposed to with a hillside where you'll have several degrees of more moderate temperature. We invested in a wind machine, which can save you several degrees on the coldest night. You know, for us now, it's about the dangers of a few hours on one or two nights. At four in the morning, when everybody else is in bed, do we turn on the wind machine, which sounds like a helicopter landing in the middle of the field, in the middle of the night? But yes, we still give it all a lot of thought.

MM: And it's not just an on and off. There are degrees of damage at degrees temperature. You know, the length of time and the temperature. So, you may lose some of the crop, but not all of it.

And what's the worst that's happened in a bad year?

MM: On a bad year, we've seen 19 below zero where we've lost almost everything. So instead of having 100% crop, we were maybe down to 20% crop.

YM: And then you're just buying your grapes. Because that's one advantage to what we're doing is that we grow the grapes, make the wine and sell the wine. So with a crop failure, we can still ... it's a big state. There'll be some part of New York State where there isn't a crop loss. So we still make the wine and sell it.

MM: But our intention is always Hudson Valley fruit, estate fruit that we grow and control. That's what we've marched to over, I guess it's 38 years I've been growing grapes. It's a long time. And that's the big variable. That's the one thing you can't control. You can't control the weather. You can do things to mitigate the problems. You have wind machines. You hill up. You try and not overcrop. You'll get good development of the shoots that develop carbohydrates, which are the antifreeze that protects the vines in the wintertime, but you do all that and it still goes wrong.

YM: And also, that's been a lot of the motivation behind planning the new vineyard at Hudson. It's avoiding having all of our chickens in one basket. Having two sites so that it's libel, you know, if we freeze out here, it's probably not gonna freeze out there.

MM: It's a special site. In the 10 years I was involved with the other vineyard just down the ridge, I never saw the site freeze out. Ever.

You grow vinifera and you also grow hybrids. Talk a little bit about what you grow in terms of the hybrids and what sort of characteristics those have.

You grow vinifera and you also grow hybrids. Talk a little bit about what you grow in terms of the hybrids and what sort of characteristics those have.

MM: You have to realize the hybrids were the first to go in to protect against winter damage. So we grow Setval Blanc. We grow Vignoles. That blend, which is our proprietary blend called the Awosting White, is our biggest selling wine even though we grow all of the usual suspects in vinifera. We grow, in fact, about 35 different varieties of grapes.

The ones that perform back in the hybrids that are sort of insurance policies against things going wrong are those two. We also grow Traminette, which is a release from Cornell University. We're linked very closely with Cornell and what they do and what they do with New York grape growers.

We grow Noiret, another red release from Cornell. We actually grow some varieties from Cornell that just have code names that were never released into production. So there were some Muscat varieties they developed about 10 or 15 years ago that still have a code name New York 84. They didn't release that, but we grow it. We make a forced carbonated Muscat wine out of it.

YM: I find the whole debate about hybrid grapes as a base for wine as opposed to European vinifera sort of frustrating I guess because hybrids have tended to be dismissed by a lot of wine critics as being the source of less serious wine. But what critics like and what the general public like is not always the same thing. And it's important to note that the wine that we sell the most of in our 7,000 to 8,000-case production is a white hybrid blend and a red hybrid blend. You know they make wines people love. And they're easier to get through the winters.

I always think back to a criticism and a discussion of hybrids that I heard a prominent wine professor articulate in a talk where he said hybrids weren't one thing or another because they're different things crossed together, and I'm just thinking, what about Cabernet Sauvignon coming from Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc. You know, that's a criticism? No. So I think they're a great source of wines in the Hudson Valley.

There's a winery in Vermont called La Garagista that we interviewed and all of her wines are hybrids and they've had-

MM: They're Minnesota hybrid.

Minnesota hybrids have had tremendous success. And the wines are selling for $50.00. And Eric Asimov from the New York Times has written very complimentary things about them. So it seems like hybrids are starting to get an acceptance now. Would you say that's true? That you're seeing some more acceptance?

MM: Hybrids are more accepted but it really comes down to the quality, number one. It's gotta be quality one. And it can't taste like Niagara or Concord. It also has to have the right price point. Nobody is going to be paying $60.00 or $70.00 a bottle for a hybrid that they've never heard of such as Marquette or La Croix or Frontenac or Baco or anything else. But they will pay high prices.

But that's really not the point. It's can you make a quality wine out of it. So it's more of a winemaker's challenge and understanding what is ripe versus what is mature. I see it way too often. People will harvest the hybrids when they're ripe but not mature, so they haven't developed the flavors yet. I will see that people still don't understand hybrid reds and their tannin structure and what you have to do to bring them into a balanced palate, and it's not really about just dumping in a bunch of tannins, which has been done in the past because, low and behold, the hybrid reds don't take up the tannins, they just fall out of solution. So you're just throwing money away.

But this is where, you know, the universities help in understanding these things has come a long way.

But this is where, you know, the universities help in understanding these things has come a long way.

YM: But selling hybrid-based wines is partly a winemaker's challenge, it's also a marketing challenge. And I think there ... I don't know if I would say there's an increased acceptance. I'm not sure I can say because we're in the privileged position of selling 75% of our wine to people who come into our tasting room and taste it. And we have no problem at all selling hybrid wines once people have tasted them. But in the other 25% of what we sell to restaurants and stores, it's definitely harder. People are going to gravitate to the bottle on the shelf that's a grape they've heard of.

So that will continue. I think everything in this business, I joke that it's practically un-American because it's not for people who are in a hurry. It's a very long time line, and building acceptance for hybrid wines is just like every other aspect of the business.

The wine that we just won Best in Show at the Hudson Valley Wine Competition for is Vidal Blanc, which is a lovely hybrid wine. It'll come.

And talking about acceptance, the Hudson Valley, I read an interview with Neil Rosenthal, which was done awhile ago, and he made the comment saying, you know, "People in the Hudson Valley should be focused on apples and not grapes and if you want to focus on grapes, go to France or Italy." I'm paraphrasing but there is that train of thought with some people in the wine industry, and then other people are very accepting of new emerging wine regions, and you guys have been extremely successful in terms of championing this region and getting on some very good wine lists.

Talk a little bit about that process of getting the Hudson Valley accepted.

MM: Well I'd love to address the issue of, you know, that the Hudson Valley should maybe stick to apples and not to grapes. A hundred years ago, the Hudson Valley was all grapes. Hudson Valley supplied the grapes from Baltimore to Philadelphia, New York, Boston. It was the grape-growing area. It happened in prohibition when the grape growers weren't allowed to grow grapes and turn them into alcohol anymore that apples took over. Apples took over and started in about 1910. So this used to be a grape-growing area.

It is one of the best areas in the state to grow grapes if you look at the number of growing degree days; so how warm is it, how long is the growing season. There's only one area, maybe Long Island, not in every year, that's better for growing. We'll beat the Finger Lakes every time. There are wonderful sites yet to be discovered in the Hudson Valley.

One of my jobs as Hudson Valley Wine and Grape Association President is convincing the apple growers to diversify out of their single focus on just apples, but to buffer their year and grow some grapes. There's a demand. You can do it. I've been successful with some growers and not others, but we're going to win that battle eventually because, with the over production, over planting of apples in the valley here, that is a cyclical business that will collapse in the future and guys will then change to growing grapes here.

The skill level is here. You know, we have really good winemakers. We have good vineyard managers. We'll go toe-to-toe with anybody in the state in terms of wine, and we've gone toe-to-toe with the California boys and won Best in Show. The San Francisco International Wine Competition for our Riesling against, oh, how many people?

YM: 1,300 white wines from 27 countries and 28 states, with 45 judges tasting blind so not bringing any preconceptions about region and regional quality. And that's an interesting wine, I think typical of what we've done over time. Our Riesling is usually a combination of grapes that we consciously source from all three regions of the state because we get different acidity levels from our own crop here and the Finger Lakes and the North Fork, so making a true New York Riesling.

YM: 1,300 white wines from 27 countries and 28 states, with 45 judges tasting blind so not bringing any preconceptions about region and regional quality. And that's an interesting wine, I think typical of what we've done over time. Our Riesling is usually a combination of grapes that we consciously source from all three regions of the state because we get different acidity levels from our own crop here and the Finger Lakes and the North Fork, so making a true New York Riesling.

And then we've regularly entered that competition because we love the fact that it's respected, it's one of the biggest and oldest in the country, but they taste blind. It's very well run. Our current Bordeaux blend, Sky Island Red, has had now gold medals two years in a row from the San Francisco International Wine Competition, which, being out there by Napa and respecting a New York red, it's just a great thing and I love to talk about how the Sky Island is a really good example of what New York can do with a great red. It's not gonna taste like a California red. It's not as high alcohol, it's not as mouth filling, but it's very complex, it's got lovely delicate flavors, it's gonna be great food wine.

So building acceptance of Hudson Valley winemaking has certainly partly been about entering competitions over the years, being rigorously persistent and determined, you know, in the face of having ... I'd pour at farmer's markets and have people, in the early days, kind of walk past looking down at me, "Local wine. I don't think so." And so it's so satisfying when you can win an award like the ones in San Francisco.

But in terms of building acceptance on getting onto great wine list, you just have to find people who are truly open-minded and that's not necessarily an easy thing but again, the persistence comes in with it and our getting onto Juliette Pope's list on the Gramercy Tavern was totally about finding somebody with an open mind.

You're on the Gramercy Tavern wine list. Talk a little bit about, you know, as one of the iconic New York restaurants when somebody talks about great restaurants in New York, people talk about Gramercy Tavern.

You're on the Gramercy Tavern wine list. Talk a little bit about, you know, as one of the iconic New York restaurants when somebody talks about great restaurants in New York, people talk about Gramercy Tavern.

YM: So we got onto the list at Gramercy back in something like 2002, 2004, early on, since our first vintage was '98. And I took my mother to dinner at Gramercy for her 80th birthday. And she, being my mother, was starting to do this sort of, "Tell them about your winery dear." And I was doing the sort of, "Shh, Mom no." Thinking that no way I'm gonna pitch our wines in here. And then I looked at the wine list and I saw that actually they had a number of New York wines, which at that time was very, very rare. There were no serious New York wine lists with New York state wines. And yet Gramercy did have them.

So then I thought, "Okay, why not?" And the wonderful Juliette Pope was there and came over and said, "Sure I'll taste your wine." And over the years of pouring for her, I've asked her where did she learn so much about wine, and she basically said there at Gramercy because she said, "Everything comes to me here. All you need is an open mind." She said, "For instance, the opportunity to taste your wines, you know, wouldn't necessarily happen in other places."

Over time, she's had our Gamay Noir, she's had our Awosting White, which is ... and I said it the way I said it just now because it's a hybrid-based wine and, in fact, I mentioned to her at the time that there's sort of a joke in the industry that we talk about vinifera racism, that there are so many people who are just automatically prejudiced against hybrid-based wines. And she sort of winced and said, "I guess we've been guilty of that 'cause this is the first hybrid wine we've had." But for her, if it tastes good, it is good.

Then for about four or five years, our Merlot Malbec has been on the list there.

Talk a little bit about the philosophy of viticulture and winemaking here.

MM: So I can easily talk about the relationship between viticulture and winemaking and it's a cliché, but it is absolutely true that the wine is made in the vineyard. If you have great grapes coming into your winery, your job is not to screw it up. If they are not at the peak of maturity, your job as a winemaker in New York is especially hard because you then have to do things to bring up the quality level, and it is a hard thing to do but you can do it by bleeding off juice. You can do it by tannin management. You can do it by yeast selection. But it takes a really good winemaker.

I joke about it with my friends in California who are winemakers. About how easy they have it every year. How it's all the same. It's gonna come in at, you know, 27 bricks and the acids are gonna be around four grams per liter so, guess what? You're going to have to look at lowering that alcohol level and you're gonna have to dump in a bunch of tartaric acid, and we have opposite challenges. But it's the inconsistency of the vintage that makes it a winemaker's challenge. And to produce good wines, you have to have a really good relationship between the winemakers and the vineyard managers. And everybody's gotta be looking at what's best for the grapes.

And in terms of the viticulture?

MM: So what I do about viticulture and what's unique and what's different is we are not organic, we are not biodynamic. We are sustainable, and I have this argument all the time with friends who are growing organic, usually not in New York. It's very difficult to grow organic in New York because black rot, there is no organic fungicide that will take care of black rot and I have a number of friends that have gotten out of the organic game because they couldn't control that. The same with biodynamic.

We are sustainable. This is our land. We are in it for the long haul, for ourselves and for our family, and this vineyard has to produce absolutely top notch every year at maximum health to sustain our business. If we don't make money out of these grapes, we will go out of business. It's that simple. So we care about it. But if you look around here and maybe you'll see it later, our house is in the middle of the vineyard. We're not gonna apply materials that poison us because we live here. So it is about minimum invasive materials. It's all about the softest materials because my crew is out here now, they're out there all the time. They don't want to be poisoned. We don't want to affect their health. I'm out here all the time.

So we do the minimum amount that's necessary to sustain our crop and bring it healthy into the year.

Take a 360 degree virtual reality tour of Whitecliff Vineyards. This experience only works in certain browsers including Google Chrome. You can also experience the VR tour directly on Youtube.

----

YM: A nice story actually I like to tell about this is I asked Michael why one section of the vineyard looked like hell. It had all these horrible little bumps on the leaves, which I didn't realize is a form of phylloxera-

MM: Aerial phylloxera.

YM: The same as root louse that took out some of the vineyards of France. And I was surprised that he had allowed something to look that bad. And he explained that we regularly have to hedge the vineyard, cut back shoots, because there's a perfect balance. You don't want to have too little leaf area to ripen the grapes but if you have too much leaf area, you'll also get vegetal flavors because the plant's putting too much energy into the leafs.

So he said we could afford to lose leaves and the phylloxera would do no more than take out some of the leaves and the spray he would have to use to control it and have it look beautiful would have gone in where there were bird's nests and baby birds in the vineyard and that's not something we do if it wasn't essential to preserve the vines.

YM: One thing I'm very proud of is the degree to which we've contributed, not just to recognition for the region, but the knowledge-base and the quality of viticulture in the region and that was really nicely recognized in 2015 when the New York Wine and Grape Foundation gave their first ever Grower of the Year Award in 30 years of giving it, to Michael. It had always gone to the Finger Lakes and the North Fork growers because that's where most of the grapes are, but we've put so much relentless determination and years into doing this.

And the new vineyard at Olana in Hudson is just a really good example of that because, you know, at a time when a lot of people would be saying, "Okay, maybe I'll sell the vineyard and put my feet up." Instead, he keeps putting in six more acres at great expense and effort. And it's really a showplace in terms of viticulture. The fact that we just took a substantial, healthy, beautiful crop of Cabernet Franc.