Benjamin Spencer, author of The New Wines of Mount Etna and Director of the Etna Wine School, is a celebrated voice in the world of wine, with a deep-rooted passion for the volcanic terroir of Sicily’s Mount Etna. As a sommelier, wine educator, and winemaker himself, Spencer brings both a scholar’s insight and a craftsman’s perspective to his exploration of Etna’s unique viticultural landscape. His book delves into the history, revival, and current renaissance of winemaking on the slopes of Europe’s highest active volcano. Spencer’s journey with Etna wines began over a decade ago, when he was captivated by the island’s dynamic ecosystem and rich winemaking heritage, which has been both challenged and nourished by the constant, unpredictable force of Etna.

With The New Wines of Mount Etna, Spencer’s goal is not only to document a wine region on the rise but to ignite global appreciation for a winemaking tradition as old as the land itself. Grape Collective talks to Spencer about the past and the future of Etna’s wine culture and the unparalleled beauty—and complexity—of this volcanic landscape.

Christoper Barnes: So Benjamin, talk a little bit about how you ended up on Mount Etna involved in the wine scene here.

(Benjamin Spencer)

So Etna filled a lot of missing spaces about what wine was and what it could be for me, but also for others. So it was more or less an interest in discovering more about wine, what wine means to me and what wine is for this part of Sicily. That really was attractive to me. So in 2012, we ended up moving here from California and I ended up falling into the wine business here as a consulting winemaker, but then also launching Etna Wine School in 2013. For me, it was the culmination of a lot of my work and a lot of my studies. I began throwing myself up and down the mountain meeting producers, tasting their wines, spending time with them and their families.

It was a journey of discovery because making wine in California is not the same as making wine on Etna. There was a lot of wine that was already sort of preconceived and discovered in California. Here, what we're seeing is that wine is being rediscovered in real time. So it's a continual adventure of discovery here on Etna from every reclaimed vineyard, every rediscovered slope, in some cases old lava flows or old winemaking facilities. So it is like discovering wine again for the first time, for me, in many cases, even after 10 years of working here.

So you came here in 2007, what was the wine scene like in 2007 on Etna?

When I arrived here in 2007 for just a short vacation, what I had discovered about Etna was very limited and this was from a California perspective. Having feet on the ground here, I discovered that a lot of things were already in play. There were producers making wine, there were vineyards being restored and it was very much a new kind of adventure for a lot of people.

However, at that same time, there wasn't a lot known about the wines or what the potential was for Carricante or Nerello Mascalese. At that same time, 2007, a lot had occurred and in that year, you start to see a lot of attention turning toward Mount Etna. You see Benanti winning winery of the year from Gambero Rosso and Slow Food. You see producers starting to set up shop here in a very scaled type of way, and repurchasing and restoring vineyards at the same time. So what had occurred in the 10 to 15 years before really created a momentum that was catching speed. So 2007, for me, is a really important moment in Etna's history. It is the moment that things really started to change.

Talk a little bit about the scale of winemaking in between 2000 and 2010. The number of producers, how big it was, because it was very different from how it is now.

So in the time that I've been here, I've seen a lot of changes. Going back 30 years, we see about five to eight wineries producing wine and bottling their wine for distribution. Now we have 165 wineries producing Etna DOC wines (as of April 2022). And that number just changed because new wineries are being formed every day, every week, every month. In that time, you also see a greater focus on larger plots owned by families, maybe for generations being restored, the edges of the vineyards being reclaimed and coming back into production. But also you see investments from outside. You see people from Belgium, from Tuscany, from other parts of Sicily, also moving toward Etna with an interest not only for the terrain but for the potential for making wine here. For me Etna has a magical flavor about it.

There's something about the tension that the volcano delivers, the sun delivers and the sea breezes give to the wines. And it's very different from neighborhood to neighborhood, from terrace to terrace and in some cases from vine to vine the types of flavors that we get. And for a lot of producers after having made maybe international varieties or other indigenous Sicilian varieties for years or decades, coming to Etna they are rediscovering the potential for variability in their own vineyards and also from vintage to vintage. This is something I think Etna does very well, just showing the changes from year to year. This was a very important thing for producers to discover for themselves. It is again like discovering wine for the first time for a lot of people from sommeliers to wine students to wine producers.

So for a lot of wineries that have moved in, but also wineries that have also maybe been growing grapes for generations have started to make wine. There was a moment following 2000, 2010, 2015 when people could rediscover the potential of Etna in a real way, and in real time from vintage to vintage. And so in a lot of ways what's happened here in the last 30 years, last 20 years, even in the last five years has been an opportunity to see what Etna is, what it can be, and maybe what the future of Etna will be.

Give us a brief history, Etna is a very old wine region and it's also a very young wine region.

Etna's wine history goes back to the eighth century BCE. Just to the north of us in Giardini Naxos you see the Greeks coming and setting up their own vineyards in the valley of the Alcantara River and from there, the wines spread around the volcano and up the volcano. And in those millennia, the wine has changed in many ways. There have been important regions in the south, on the southeast, on the east and in the north. And each one of them has their own period of time of importance. This current wave that we are seeing in Etna's history is possibly one of the most important since the outbreak of phylloxera in the European continent at the end of the 1800s, when merchants turned to Etna to supply the wine economy of France, of Northern Italy, of Southern Spain. When the phylloxera was taking over the vineyards there at that time, Etna was producing about 55% of all of the wine in Sicily.

Now we are seeing just a fraction of that wine being produced, about four million bottles per year, with an enormous amount of space still available to growers to expand their vineyards, to grow their projects. But at the same time, there wasn't a real inclination toward focusing on high-quality wines back during the phylloxera outbreak. The important thing then was providing Vino da Tavola or blending wine to producers in the north of Italy. Now it's producing high-quality bottled wines for in some cases, very small niche markets or very large markets like the United States. For Etna the number one issue, the number one problem to solve, and the number one goal is to make the best wine possible year in and year out. And that's the new standard.

And let's talk about the culture of Sicily in general, in terms of it has been invaded by multiple cultures, multiple countries, and each has added sort of a sprinkling of flavor to what exists today as modern Sicily. Maybe you can just give us a little bit of background on that.

The history of Etna is thousands of years old, especially in terms of the wine production here, we see about 6,000 years of continuous history. Some of that is recorded. Some of that is absolutely unknown, but what we do see is with every wave, every new culture, every occupying country or economy that set foot on the island and set foot on this eastern half of Sicily, Etna played a major role in what they were producing and the economies of scale that they were interested in. For many of those cultures, for many of those occupiers, it was an important area of interest.

For example, the area around Catania and the southern slopes of Mount Etna was very popular in the early to late medieval period. You see in the late medieval period to the Renaissance that the east slope became very important. And then following the 1693 earthquake that rattled much of Southeast Sicily to the ground, you see a tsunami bringing the sands up onto the beach behind us and allowing merchants to slide their ships up onto the sea, making the area around here incredibly important for vineyards and for the new wine grape Nerello Mascalese.

Following that you see an explosion of interest for cutting wines or blending wines, Vino da Tavola, during the phylloxera outbreak in the later part of the 1800s. There were even specialist merchants arriving as late as the 1920s and 1930s looking for specific qualities of wine for blending up different types of wine for their consumers or their clients in Northern Italy, in Malta and Southern France, even wine bars in the Veneto. But this most recent initiative was followed by a very long period of downtime, which followed the second World War.

Following that you see an explosion of interest for cutting wines or blending wines, Vino da Tavola, during the phylloxera outbreak in the later part of the 1800s. There were even specialist merchants arriving as late as the 1920s and 1930s looking for specific qualities of wine for blending up different types of wine for their consumers or their clients in Northern Italy, in Malta and Southern France, even wine bars in the Veneto. But this most recent initiative was followed by a very long period of downtime, which followed the second World War.

World War II absolutely devastated this eastern part of Sicily and Mount Etna. And you see a lot of rural flight following that period. A lot of the countryside was being abandoned. And you end up with vineyards that were managed by in some cases one or two people, and in a lot of cases went to waste. Some higher parts of the terraces were allowed to go wild, again, returning to Etna. But following the 1990s and a reinitiative toward making quality wines with Carricante and Nerello Mascalese, you see a real renewed interest in making something different from the indigenous varieties that have grown here for a very, very long time. You see the inclination for a lot of wineries to begin experimenting as well. In some cases with the international varieties that were planted here, following World War II.

And I think a lot of people's opinions is that the grapes that have grown here, the grapes that were brought in by maybe the Greeks, maybe during the Crusades, maybe from the Benedictine and Capuchin monks, maybe from the Bishop of Catania or the Spanish, every grape, every little heritage, every Relic variety has contributed something special to the grapes that are here now. And so what we're left with is Carricante and Nerello Mascalese, but then also some indigenous cultivars, in some cases, one vine per vineyard, or five vines per vineyard.

This added something really unique to what's here, so every vineyard may have some Carricante or some Nerello Mascalese, but they'll also have Col di volpe, Grecanico or Minnella Bianca, Minnella Nera, Zu'Matteo, in some cases on the southeast slope, and you'll have something unique from each and every vineyard. So this is one of the special things that makes Etna unique in all the world. This history, this blending over time, this stratification of flavor and the brilliant weather that we have in the volcanic soils that contribute a lot of that dynamic minerality and add a lot of texture to the wines that end up in your glass.

Talk about the current state of affairs in the wine community here. You have a lot of very interesting backgrounds, Belgium, Spain, the United States that are all adding to the increase in quality you see today in Etna. There feels to be something more inclusive about Etna because of this sort of generation after generation change in the composition of the people and the culture.

I think there's a lot to be said about the multicultural community here that's on Etna. It's very international. There's a lot of interest in Etna from outside, possibly because it's a volcano, possibly because of the dynamic flavors that we get in the food and in the wine, but whatever it is, that is attracting people to Etna. The one thing that is sort of a continuing thread throughout time is that it is attracting everyone. It's a place that anybody can succeed at what they want to try. It is a place that is open to discovery, open to initiative, open to a new understanding of what the potential is. And so I think in a lot of ways what Etna has created is an extension of this multinational history that has been, that has created it, or has been at least a part of the culture and a part of the edifice of this place for thousands of years.

It is a stratification of terrain. It's a stratification of cultures, but it's very much in play today. You have Belgium producers, you have Spanish producers, you have Northern Italian, you have Asian producers all looking at Etna with the possibility that this is a place that they can live a good life, but they can also make something unique, something that they can really call their own. And I think that's very inviting, it's not very cookie cutter. If you know what I'm saying, it goes beyond that. It's very much a free-form place. You can create your destiny in a lot of ways.

Talk about the origin of the volcano. You have the African plate and the Eurasian plate. How did we get here?

So Mount Etna is 10,600 feet tall. Currently it is roughly 3,470 meters above sea level. It was formed beneath the sea and a shield volcano about 500,000 years ago where the African plate was subducting beneath the Eurasian plate. And this intersection created a hotspot beneath the water, a shield volcano that continued to spread on the sea floor, rising strata after strata, until it poked out of the surface of the water. And this sub-aerial expression of Mount Etna began to grow. It formed a number of different volcanic moments and volcanic hotspots around a very large bay, which is what Etna has assumed the space of behind me. And what you see is a stratification of at least nine different epics of volcanic activity, some of them moving to the southeast, some of them moving back to the east and eventually just building on each other in rock and sand in both effusive or liquid lava flows in lava fields.

So Mount Etna is 10,600 feet tall. Currently it is roughly 3,470 meters above sea level. It was formed beneath the sea and a shield volcano about 500,000 years ago where the African plate was subducting beneath the Eurasian plate. And this intersection created a hotspot beneath the water, a shield volcano that continued to spread on the sea floor, rising strata after strata, until it poked out of the surface of the water. And this sub-aerial expression of Mount Etna began to grow. It formed a number of different volcanic moments and volcanic hotspots around a very large bay, which is what Etna has assumed the space of behind me. And what you see is a stratification of at least nine different epics of volcanic activity, some of them moving to the southeast, some of them moving back to the east and eventually just building on each other in rock and sand in both effusive or liquid lava flows in lava fields.

And then also explosive lava flows. We end up with a single volcanic cone called the Elliptical volcano, which erupted about 15,000 years ago, or slightly more. The Elliptical volcano recreated or rearranged the plumbing of the volcano. So we have the Elliptical volcano forming the breadth and width of the mountain that's now called Mount Etna. And then the explosive activity of the Mongibello volcano, which is the current edifice that we see at the edge of the Ionian sea, the eruptions following this recreation of the volcano, the Mongibello creation is what we see most today. We have about 85% of the mountain covered in volcanic debris, rock, sand, basalt, silica loaded with iron, also aluminum, magnesium, and other essential minerals. What we also see are little out-croppings, where the eliptico volcano still is present.

About 15% of the mountain still has exposures of prehistoric volcanic debris. And some of that debris is still accessible to volcanic winemaking teams, wineries that are working on the north slope, for example, have access to the eliptico volcano. Winemakers on the south also have access to soils that were formed thousands of years before that. And what we're dealing with currently with the Mongibello volcano is a composite of soils that are 15,000 years old or younger. This is a very important thing to consider. We also have a different aspect, different slopes, different ventilation around the volcano, and also different elevations that give ripening at different times during the harvest. So it's a composite of sand and rock, but it's also a composite of weather. We have incredible breezes, bright sunlight, but also the arc of the sun changes depending on the seasons.

I think Jancis Robinson said something about how Etna has a Burgundian-like quality in the unique microclimate. How does the volcano express its uniqueness?

The expressions of Carricante or some Nerello Mascalese change often from meter to meter. This is where we see a lot of the comparisons between Burgundy, even Piedmont and Mount Etna with the subtle variations of soil of aspect and elevation, the amount of sunlight that a vineyard gets. You do see these increases in minerality or acidity or fruit. And even with the changing vintages, you see the same thing. So in a lot of ways, the band of the Etna DOC, which is approximately 45 kilometers long, very similar to that of Burgundy, you see a mosaic of different soil types, elevations, and expressions that can come across in the grapes. One thing that is very important to remember about Etna varieties is that they reflect the terrain, where they're grown. Very much like Pinot Noir reflects the terrain where it's grown, Nerello Mascalese and Carricante reflect the soils, the moisture, and the stones that are in the soil where it is planted.

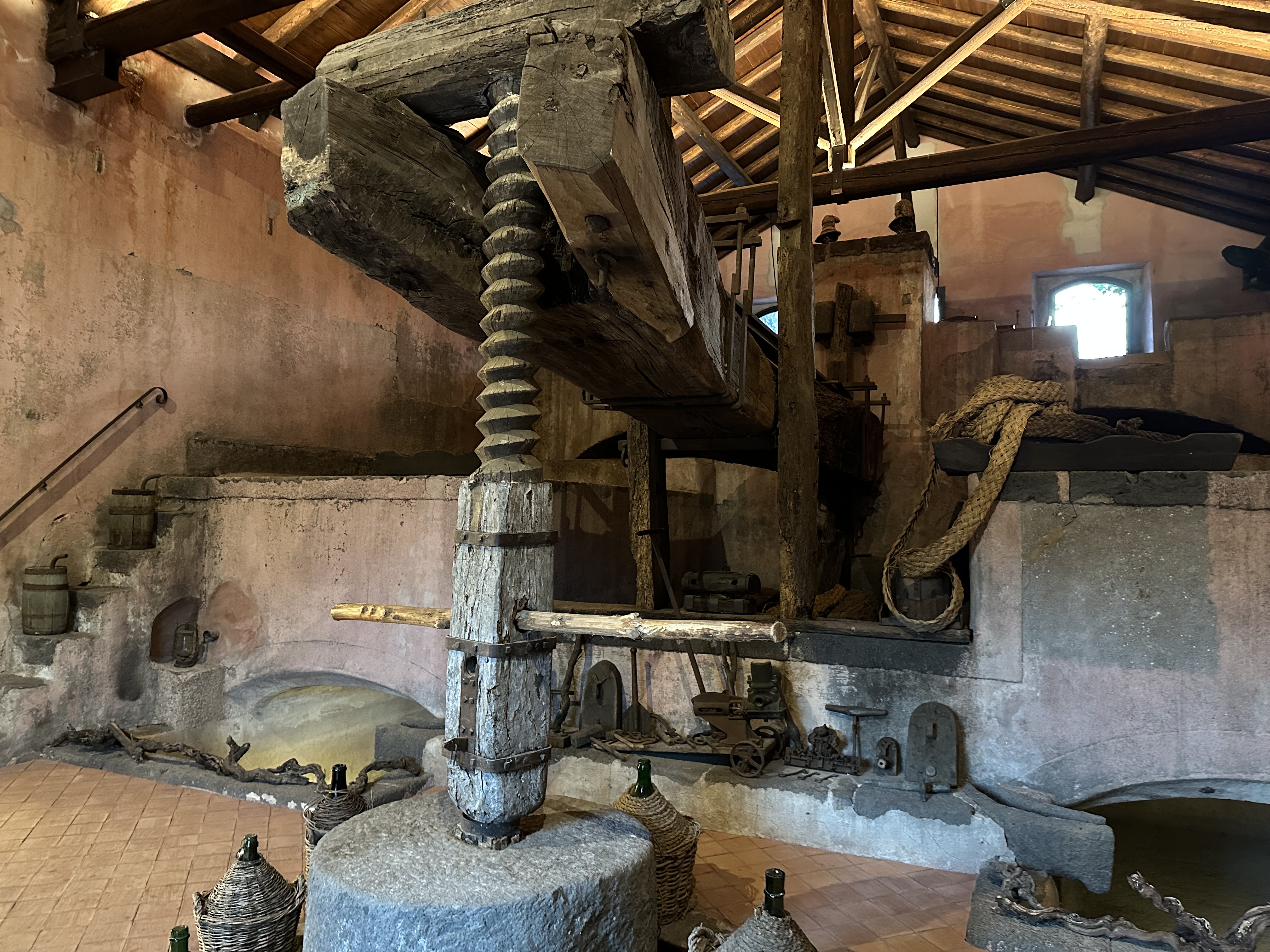

So Benjamin, you have this historical way of making wine on Etna that has been used for a long time that has been stopped by government regulations. Some of the producers, including Salvo Foti, are fighting back, fighting for their heritage. Talk a little bit about the story of palmento and where we are with it.

Palmento is a gravity-operated stone winemaking facility or winemaking facility formed in stone. It is a tradition to make wine in this way, going back thousands of years. The EU effectively in 1978 made these facilities illegal for more or less bureaucratic reasons because of the potential sanitation issues with maintaining these facilities. In recent years, there has been a lot of effort to restore the use of these facilities in some cases by producers who are making Etna DOC wines, but also bringing people into their facilities to show them the importance of this tradition and continuing the tradition.

Palmento is a gravity-operated stone winemaking facility or winemaking facility formed in stone. It is a tradition to make wine in this way, going back thousands of years. The EU effectively in 1978 made these facilities illegal for more or less bureaucratic reasons because of the potential sanitation issues with maintaining these facilities. In recent years, there has been a lot of effort to restore the use of these facilities in some cases by producers who are making Etna DOC wines, but also bringing people into their facilities to show them the importance of this tradition and continuing the tradition.

(Benanti winery palmento)

Reclaiming the tradition of making wine in palmento is a great part of Etna's heritage. And considering that no human pathogen can be found in any wine made in these facilities, it makes no sense to keep them outside of the Etna DOC legislation. In my opinion, some of the best wines that I've had have actually been made in palmento. I won't tell anybody that, but it is the truth.

There's something magical about making wine on this volcano that attracts people from all over and the magic is somehow transmitted into the bottles that people drink. There is something magical about this place with the lava and the smoke.

There's something really magical about Etna for me and that juxtaposition of fire and water, these two essential elements within the world, making wine between these two, these two sacred elements is I think incredibly attractive to a lot of people. It's this tension. I think that we feel within the stones and within the minerality that is expressed through the wines that are made here and this unique combination, fire, water, stone, and the work that men do and women do on this mountain, I think is the greatest attractor for what we see in Etna and what we feel in Etna. There's an energy, a very positive energy, that comes through in the wine that we find in our glass. And that is a direct response to all of these elements, all of these compositional pieces that play together in this incredibly dynamic place.

And Etna's come so far in such a short period of time. What do you think is next for Etna?

Etna is on a path toward incredible things. I believe that I changed my life and moved here 10 years ago because I believe in Etna, 100%. Etna's future is still a little bit undetermined, but what I see is incredible wines, amazing food, adventure at every turn and just enough uncertainty to keep things interesting.