We adore our daughters. Still, since they started living under their own roofs, we have looked forward to them leaving town. Lucky for us, Media and her husband, José, are inveterate travelers and Zoë is a professional drummer who tours. We miss them when they are away and beg for pictures. But the reason we also look forward to their trips is because they allow us to stay at their apartments in different zip codes and that provides us with an opportunity to discover restaurants with new, tantalizing wine lists.

We have just returned from a few days at Media and Jose’s apartment in Brooklyn, where once again we had a wine at Saint Julivert Fisherie and Wine Bar that made our socks roll up and down. Last year, while enjoying Saint Julivert’s delicious and imaginative dishes, we discovered a Hoof & Lur skin-contact orange wine made from Moschofilero grapes by Troupis Winery in Greece. This time, we had The Scythians 2022 Palomino from Cucamonga Valley near Los Angeles. Yes, that Los Angeles. What’s more, it was made by Rajat Parr, who has been hailed as one of the greatest sommeliers of our time and who left that behind to work with wunderkind Sashi Moorman, both of them founding partners, proprietors and winemakers for Sandhi Wines and Domaine de la Côte in the Sta. Rita Hills in Santa Barbara, California; and biodynamically grown Evening Land Vineyards in the Eola-Amity Hills of Oregon. The Scythians 2022 Palomino retails for about $60.

We have just returned from a few days at Media and Jose’s apartment in Brooklyn, where once again we had a wine at Saint Julivert Fisherie and Wine Bar that made our socks roll up and down. Last year, while enjoying Saint Julivert’s delicious and imaginative dishes, we discovered a Hoof & Lur skin-contact orange wine made from Moschofilero grapes by Troupis Winery in Greece. This time, we had The Scythians 2022 Palomino from Cucamonga Valley near Los Angeles. Yes, that Los Angeles. What’s more, it was made by Rajat Parr, who has been hailed as one of the greatest sommeliers of our time and who left that behind to work with wunderkind Sashi Moorman, both of them founding partners, proprietors and winemakers for Sandhi Wines and Domaine de la Côte in the Sta. Rita Hills in Santa Barbara, California; and biodynamically grown Evening Land Vineyards in the Eola-Amity Hills of Oregon. The Scythians 2022 Palomino retails for about $60.

Parr, we discovered, has been putting his considerable focus and energy into two different low-intervention, small-production wine projects. Scythian Wine Co. made the Palomino, a dry, mineral-driven, mid-weight almost orange wine that was pitch-perfect first with our hushpuppies and anchovies and green herbed butter and then with our whole fried fish.

The 2022 Palomino, Parr’s second release from Lopez Vineyard, came from rugged, own-rooted vines planted more than a century ago when Los Angeles was one of the most prolific hubs for grape growing (Garnacha, Mission or Pias, Palomino, Tintorera and Zinfandel) and winemaking in the nation.

Parr’s second enterprise is Phelan Farm Wines in San Luis Obispo County, inland from the Pacific on the Central Coast. The Phelan Family had been farming there for decades when Greg Phelan decided to plant own-rooted Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Between 2017 and 2020, Parr expanded those plantings by grafting acres of vines there to Trousseau, Gamay, Gringet (we had a fine example of that, from France, at Big Tiny), Mencia, Mondeuse, Savagnin Vert, Savagnin Jaune, Poulsard and Jaquesse. And because he’s been having fun with Palomino from Lopez Vineyard, which the Galleano Family has overseen for generations, Parr planted some Palomino at Phelan Farm. The two projects are in such disparate regions that their harvest times do not overlap. We caught up with Parr by phone recently during a brief spell between the two projects.

“We just finished the last pick just a few days ago,” he said of the 15 acres of Palomino. “This is from an old vineyard planted in 1912 in Cucamonga. This region had thousands of acres planted and was forgotten about and then we, me and my friend Abe Schoener, found these vineyards in 2018 and went in and started to make wine from 2021. It was pretty much forgotten. No one had made wine from there for a very long time and the Palomino was not harvested by a lot of people when we found it and only a few acres had been pruned. There was more Zinfandel.”

“We just finished the last pick just a few days ago,” he said of the 15 acres of Palomino. “This is from an old vineyard planted in 1912 in Cucamonga. This region had thousands of acres planted and was forgotten about and then we, me and my friend Abe Schoener, found these vineyards in 2018 and went in and started to make wine from 2021. It was pretty much forgotten. No one had made wine from there for a very long time and the Palomino was not harvested by a lot of people when we found it and only a few acres had been pruned. There was more Zinfandel.”

(Rajat Parr)

It was like finding a diamond in the rough. The dry-farmed vines, in sand and granite, had never been treated with pesticides or had tractors driven between their rows. He and Schoener, of the natural wine phenomenon the Scholium Project, are keeping it that way, except for pruning a bit. They pick at the same time and then make their wines at different wineries, Schoener at his downtown Los Angeles winery, LA River Wine Company, where Parr made his first release, and Parr now at a small winery in Orcutt in Santa Barbara. The wine we had, the 2022, was made in Lompoc, where Moorman and his wife, Melissa Sorongon, have a winery, Piedrasassi, and an artisanal bakery. Moorman also has a winemaking consultant and wine-focused human resource company called Provignage.

Parr, who grew up in Calcutta and has worked in some of the most prestigious restaurants in the world, doesn’t seem like the kind of person you would find around sheep, goats and chickens and dogs that guard them in vineyards, but that’s part of what he’s doing now as a grape farmer doing things in a low-key, naturalistic way. How did he get there, we wanted to know.

“I was tired of traveling, being everywhere. I moved to Cambria [in San Luis Obispo County] and decided to start farming and ended up here and found these old vineyards so now I’m a fulltime farmer,” he told us.

That’s a significant life change. “Yeah. For sure. It’s great. I love it. I was just tired of flying. I just saw the pollution from the air travel and I just wanted to do something wonderful and useful, try to focus on regenerative farming. I’m trying to focus on a region and farm and learning how to grow grapes and work vineyards with minimum inputs, low intervention. It’s like permaculture,” he said, referring to an agriculture philosophy from Masanobu Fukuoka, whose writings he has read in addition to books by soil microbiologist Elaine Ingham. The droppings from the sheep, goats and chickens that are moved around the vineyards—and guarded by the dogs—help keep the soil brimming with plant nurturing life. After the Palomino is hand-harvested and macerates on its skins and ferments with indigenous yeast, it gets a little bit of sulfite and is not fined or filtered.

That’s a significant life change. “Yeah. For sure. It’s great. I love it. I was just tired of flying. I just saw the pollution from the air travel and I just wanted to do something wonderful and useful, try to focus on regenerative farming. I’m trying to focus on a region and farm and learning how to grow grapes and work vineyards with minimum inputs, low intervention. It’s like permaculture,” he said, referring to an agriculture philosophy from Masanobu Fukuoka, whose writings he has read in addition to books by soil microbiologist Elaine Ingham. The droppings from the sheep, goats and chickens that are moved around the vineyards—and guarded by the dogs—help keep the soil brimming with plant nurturing life. After the Palomino is hand-harvested and macerates on its skins and ferments with indigenous yeast, it gets a little bit of sulfite and is not fined or filtered.

It was also a change in the way he and Moorman had been working. While Moorman was able to stay close to home when his daughter was born, Parr was more of the public face of their joint endeavors. Now that Moorman’s daughter is older, Parr has been able to step back from a lot of that.

Since many of the Palomino vines are more than 100 years old and untouched by chemicals, we wondered whether any lessons could be drawn from their continued survival.

“I think it’s pretty amazing that these vineyards without any human help have lived this long and are healthy. They are super healthy vines. They’re strong vines, not weak by any stretch of the imagination and they have a long way to go. They don’t get any compost, they don’t get anything,” Parr said.

With climate change affecting so many things but especially with what you’re doing now, farming, have these old vines taught you anything about nature?

“One hundred percent, we’ve learned from these wines. They have taught us so much, especially how resilient they are. You just have to believe in the system. They’ve been through severe droughts, they’ve been through not pruning for years and years. They’re resilient and they produce fantastic wines.”

“One hundred percent, we’ve learned from these wines. They have taught us so much, especially how resilient they are. You just have to believe in the system. They’ve been through severe droughts, they’ve been through not pruning for years and years. They’re resilient and they produce fantastic wines.”

Palomino is best known as the grape of sherry and after it is hand-picked, it is fermented and aged in old French oak barrels and, from Ramiro Ibanez in Sanlucar, Spain, old sherry barrels that are not topped off for six months to allow for the miracle of the flor, a cap of indigenous yeast cells that protects the wine from oxygen. Parr is wild about the 2021 because “we had lots and lots of flors,” he said, "which gives the wine a savory quality, that flor-like aroma. It’s outstanding.” After we had the 2022 at the restaurant and called Parr, he sent us the 2021 and it is indeed a special experience -- cloudy, a bit orange, with the tangy, fleshy acidity of tangerines and kumquats. It did remind us of a very dry sherry. It was a touch edgy with a rusticity that translated as a pure expression. It was delicious and real.

He made 300 cases of the 2022, which was 95 percent Palomino and 5 percent “unknown” varieties. Unknown? We asked. “Yes. There are a lot of varieties growing together so there are some red grapes in there. That’s why it has the pinkish-orange tint." The 2022 got skin contact and right now, the just-picked 2023 is fresh, he told us. "We’ll see if the flor comes.

“Every year we think of different ways to showcase the grape. This year I’m making a sparkling Palomino. It’ll be released next fall.”

We can’t wait.

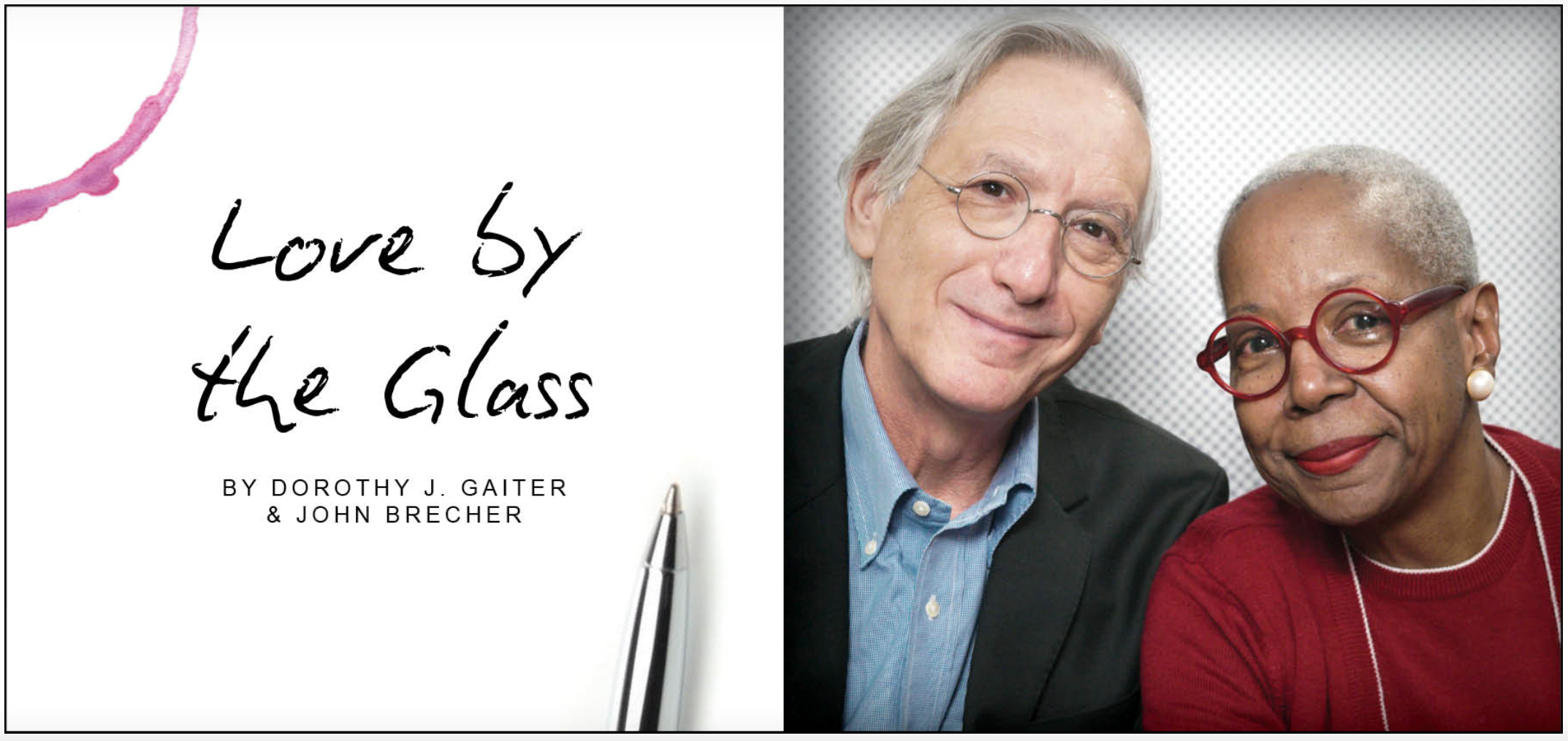

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett