We grabbed a bottle of wine and walked over to Central Park to watch people watch the eclipse. It was like a giant party. Young children were chanting, “Go, Moon! Go, Moon!” Three teenagers were selling eclipse glasses for $5 each. Some people were wearing weird New Age outfits.

It was such a beautiful day that we thought a rosé might be in order. We didn’t have eclipse glasses for this momentous event but we could experience it with a rose-colored wine, right? So John grabbed the Dianthus Rosé 2023 from Tablas Creek Vineyard that a winery representative had sent and we found space on a bench facing the reservoir. For about two hours, we talked about the mind-tickling wine and watched the eclipse’s shadows play on the sidewalk while our neighbors looked upward, spell-bound.

It was such a beautiful day that we thought a rosé might be in order. We didn’t have eclipse glasses for this momentous event but we could experience it with a rose-colored wine, right? So John grabbed the Dianthus Rosé 2023 from Tablas Creek Vineyard that a winery representative had sent and we found space on a bench facing the reservoir. For about two hours, we talked about the mind-tickling wine and watched the eclipse’s shadows play on the sidewalk while our neighbors looked upward, spell-bound.

(Watching the eclipse)

We have been fans of Tablas Creek, in Paso Robles, since we stumbled upon its white at the California Grill in Disney World in 1999. The winery was founded in 1987 as a joint project of the Perrin family, of Château de Beaucastel in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and the Haas family of Vineyard Brands. It has been a leader of Rhône varieties in the U.S. and produces about 30,000 cases. It’s organic, biodynamic and regenerative organic.

Tablas Creek makes two rosés, Dianthus (1,380 cases, $40) and Patelin de Tablas Rosé, which we also liked (5,250 cases, $28). Dianthus, named for a genus of flowering plants that’s also known as “pinks,” is 51% Mourvèdre, 38% Grenache, 8% Counoise and 3% Cinsault. It’s fermented in stainless steel and, to us, seemed so dry that it almost had an edge despite its juiciness, which is quite a balancing act. After a few sips, we wished we’d brought over dinner to have with it on a blanket.

Whenever we have a wine that strikes us deeply, we know there’s a story we want to hear. We have found Jason Haas, the second-generation partner and general manager of Tablas Creek, to be particularly thoughtful and eloquent over the years. So we called him to learn more about this wine – and, of course, it turns out that the story begins with his mother, Barbara, now 83. The following has been edited for length.

Grape Collective: Big question first. Why do you make rosé?

Haas: We started making rosé way back in 1999, really before any of the leading ripples of the rosé wave had hit in the United States and it was originally my mom’s idea. She decided after a trip to visit Beaucastel that it was crazy that we were growing these grapes that made such wonderful rosés in the south of France and not making something to drink ourselves. So it was not really a commercial idea at the beginning. We made three barrels of rosé in 1999 and we honestly expected that we would end up drinking most of it. We did release a little bit of it and it sold well and it has basically built from there.

It was really before the rise of Provence-styled rosé in America, so we actually looked to Bandol and Tavel for our inspiration. So we tried in our experiments making it kind of Bandol style -- Mourvèdre-driven, not a lot of skin time, fairly short soak -- but decided that there was enough lushness, enough richness that we needed a little bit longer soak, a little bit more of the bite from skins to balance the richness of the estate Mourvèdre. And that was how we landed on the model that we still use on the Dianthus, a little more than half Mourvèdre and a little less than half the other southern Rhône varieties. [More technical information here.]

It was really before the rise of Provence-styled rosé in America, so we actually looked to Bandol and Tavel for our inspiration. So we tried in our experiments making it kind of Bandol style -- Mourvèdre-driven, not a lot of skin time, fairly short soak -- but decided that there was enough lushness, enough richness that we needed a little bit longer soak, a little bit more of the bite from skins to balance the richness of the estate Mourvèdre. And that was how we landed on the model that we still use on the Dianthus, a little more than half Mourvèdre and a little less than half the other southern Rhône varieties. [More technical information here.]

(Tablas Creek's Jason Haas with Sadie)

GC: And you still use the same vines?

Haas: That very first year we decided that the lot that made sense to make rosé out of was our nursery block, which is in a coolish part of the property and it’s not a spot that we would normally plant grapes likes Mourvèdre and Grenache and Counoise, but in that era we put everything on that one hillside so it was convenient to the grapevine nursery. We only had five rows of each variety that we planted back in 1994 and we were pulling cuttings from them to propagate and graft and plant the rest of the vineyard. So what it meant was that that section ripens quite a bit later than other blocks. And since they were such small blocks, just these five rows of each variety, we decided to co-harvest and co-ferment the Mourvèdre and Grenache and Counoise – kind of when the Grenache was ready, which is kind of on the early side for Mourvèdre and Counoise. That worked great since it was going to be used for rosé anyway.

GC: So this wine really is a little slice of history. We think many people still see rosé as a soft, maybe slightly sweet sipper. Isn’t it challenging to sell a dry rosé?

Haas: No. I think rosés are most successful when they have this kind of vibrant fruit but are also fully dry. That seems to me to be the style people mostly gravitate towards. The thing that requires a little bit of contextualization for people sometimes is that it’s a darker rosé, with deeper color and more time on the skins than what I think people expect in this day and age. People are expecting Provence or expecting something that is influenced by the style of Provence, where it is very much a white-wine style of rosé where you’re focused almost exclusively just on the flesh, the juice of the grapes, and not so much the skins, where there’s just enough color that people know it’s not a white wine but it’s supposed to taste more or less like a white. This is not that. This is more of the Tavel tradition, where it’s made a little more like a red is, where you get more of the texture and the flavors and the complexity you would get from the skins of the grapes because it spends longer on those skins.

There is a whole generation of rosé drinkers in America who came to rosé in this Provence era and they often will look at something like Dianthus and think, oh, this is going to be sweet, this looks like White Zinfandel. We find that we often have to tell the story that, no, there are other rosé traditions. That’s the piece that sometimes confounds people with this wine, but not the fact that it’s dry.

GC: When we were drinking the wine in the park, we talked about how it seemed so much like strawberries and like watermelons, but fully dry strawberries or watermelons, which was interesting. Does this seem weird to you?

GC: When we were drinking the wine in the park, we talked about how it seemed so much like strawberries and like watermelons, but fully dry strawberries or watermelons, which was interesting. Does this seem weird to you?

(Dottie with Dianthus)

Haas: Not in the least and in fact those are the two main fruit tones that we get. The main fruit tone from Mourvèdre made into rosé is watermelon and the main fruit tone when Grenache is made into rosé is strawberry. And those are the two major components of Dianthus.

GC: Is it a challenge to get people to pay $40 for a bottle of rosé?

Haas: I think Bandol has led the way a little bit for that. When people ask us that, we say, well, this is 100% from our estate. That farming has real costs to us. And the quality of wine is real in the bottle. It is not a rosé that we would expect people to have a case of and just open a bottle on a regular Wednesday evening sitting by the pool. That’s not what this rosé is about. It’s not your everyday rosé. It’s not supposed to be. It’s supposed to be an example of something special for a special occasion and, for that, I feel that’s not a big ask.

GC: We called this a white tablecloth rosé. Do you think Americans are used to serving rosé with the finest meals or is that a leap?

Haas: It’s one of the ways we talk about Dianthus being a little different from most of the rosés most people encounter. This is a rosé that’s a little more of a gastronomic kind of wine, something that would be paired with a meal. Dry rosés are incredibly flexible and friendly with food. The Dianthus is absolutely a food wine. I think it is one of the things that helps people put that wine into context because it is an outlier in a lot of people’s experiences. Like, OK, this is a rosé that I should think about pairing with food.

I remember a dinner I did six or eight years ago where the Dianthus was paired with a spice rubbed quail with a salted watermelon feta salad and it was one of the best pairings I’ve ever done in all of the wine dinners I’ve ever hosted.

GC: Oh heavens.

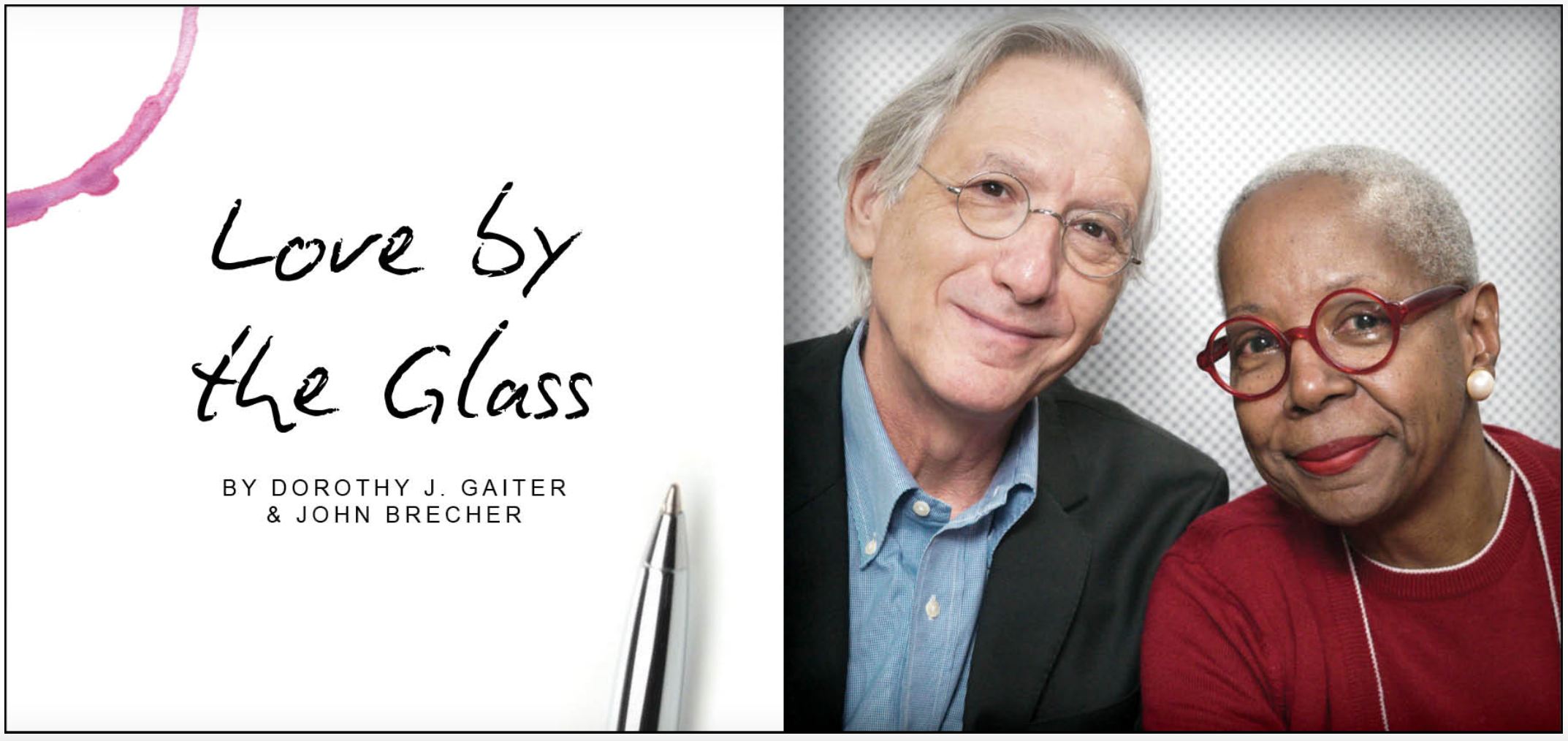

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett