We’ve been drinking wines from Alsace for decades and have especially enjoyed those from Domaine Paul Blanck in Kientzheim. So it was wonderful to finally meet Philippe Blanck, who runs the business now with his cousin Frédéric.

One reason we’ve appreciated wines from Alsace is that they are tremendously distinctive, unflaggingly aromatic and have such astonishing versatility that we’ve had them with dishes from all over the world, often at Indian restaurants. Alsace’s location and diverse soils in northeastern France, along the borders of Germany and Switzerland, probably aids that gustatory chameleon effect. Whatever. To sip a fine wine from Alsace is to appreciate that you are having an experience, whether it’s a peppery Gewürztraminer; a dry, nose-tickling, minerally, walks-a-fine-acidic-line Riesling; an earthy Pinot Blanc or Sylvaner; a floral Pinot Gris or Muscat; a rose-scented, soul-piercing Pinot Noir; a juicy apple-peel or grapefruit-zest Crémant d’ Alsace sparkler; a luscious, sweet Vendanges Tardives or other grape type or style. When well-made, they stick in the memory.

We met Philippe, 64, at a recent event in New York City called Alsace Rocks, sponsored by Wines of Alsace USA. There were more than 150 wines with 11 producers pouring wines from their ranges, some including entry-level wines, reserves and Grand Crus, of which Alsace has 51. There were also tables devoted to specific grape varieties.

We met Philippe, 64, at a recent event in New York City called Alsace Rocks, sponsored by Wines of Alsace USA. There were more than 150 wines with 11 producers pouring wines from their ranges, some including entry-level wines, reserves and Grand Crus, of which Alsace has 51. There were also tables devoted to specific grape varieties.

(Philippe Blanck and Dottie)

Meeting Blanck gave us an opportunity to thank him for his family’s contribution to our wine journey. As we chatted, acknowledging our fondness of well-aged fine wines, he poured splashes of the domaine’s stunning 1993 Pinot Noir. A natural storyteller and towering over us, he rattled off the names of famous restaurants and sommeliers that have carried his wines over the years. “Coming to New York is like a pilgrimage,” he told us, adding that he was on a mission to share the region’s wines with a new generation.

The Blanck family has been dedicated to winemaking in Alsace for centuries. According to its website, Hans Blanck planted vines there in 1610. Jacques Philippe Blanck was honored as a winemaker in 1846. The domaine was founded in 1921. In 1927, Philippe and Frédéric’s grandfather, Paul Blanck, and other winegrowers worked Schlossberg into a site fit for grand cru status. In 1975, when the grand cru appellation system in Alsace was created, their dreams were realized with Schlossberg becoming the first vineyard to earn the designation. In 1984 Philippe and Frédéric took over from their fathers, Marcel and Bernard, respectively. Frédéric, 60, makes the 35 wines (120,000 bottles annually, 20% stays in France and 20% goes to the U.S.) and oversees the organically farmed vineyards (including five grand crus and four lieux-dits, potential grand crus). Philippe handles communications and is viewed as an ambassador for the industry, which is composed of 720 wineries, 3,030 grape growers and 38,500 acres of vineyards that produce more than 132 million bottles. We called Philippe after he’d returned home to ask him about the state of the wine industry there. This has been edited.

Grape Collective: What makes the wines of Alsace special?

Blanck: Our goal is to create wines with a strong personality, with minerals, because we trust the terroir. Single vineyards are the future of our viniculture. You can produce Riesling and Pinot Blanc all over the world but it’s not the same as here in these vineyards. You can make Chardonnay all over the world, but it’s not the same as in Burgundy. In Alsace we have a diversity of grape varieties and on top of that a great diversity of soils, 13 types, so we can adapt the grape to the soil.

GC: What trends do you see?

Blanck: With the price of Burgundy high, people will buy more and more single-vineyard Pinot Noir from Alsace and vineyard prices will continue to increase. Also, two other things are pushing Alsace up. Sparkling wine, Crémant, has had large percentage growth in 20 years, with one-third of wines AOC Crémant d’Alsace. It’s the second most popular sparkling wine in France after Champagne. And there is a very strong evolution in white wines, mostly Pinot Blanc and Riesling. [Whites made up 89% of the wines produced in Alsace.]

Blanck: With the price of Burgundy high, people will buy more and more single-vineyard Pinot Noir from Alsace and vineyard prices will continue to increase. Also, two other things are pushing Alsace up. Sparkling wine, Crémant, has had large percentage growth in 20 years, with one-third of wines AOC Crémant d’Alsace. It’s the second most popular sparkling wine in France after Champagne. And there is a very strong evolution in white wines, mostly Pinot Blanc and Riesling. [Whites made up 89% of the wines produced in Alsace.]

(1993 Blanck Pinot Noir)

GC: Does Paul Blanck make a Crémant?

Blanck: We decided to stop a few years ago. Pricing was so low so we stopped so we were not running into the spiral. A lot of top producers don’t produce Crémant. They don’t have enough margin. But the quality has never been better. People know how to do it now. There are positive points and negative points. We are independent growers and we have another conception of our job rather than the cooperatives and négociants.

GC: How are Rieslings selling?

Blanck: Rieslings from single vineyards and grand crus, they are outstanding. There’s been a good evolution in the wines.

GC: And Gewürztraminer?

Blanck: We trust in Gewürztraminer, but some people don’t trust in Gewürztraminer anymore so they’ve pulled it out and planted Pinot Noir. We sell five percent more every year. All over the world it’s a great food-pairing wine in China, India, Thailand, Hong Kong, even in the United States with fusion food.

GC: Is Alsace a tourist destination?

Blanck: We have less than 2 million inhabitants and we can go to 20 million people visiting each year, peaking in 10 million in December, the Christmas market. Visitors come from all over the world for the Christmas fairs and holiday traditions.

GC: When you and Frédéric took over from your fathers, did you face any unexpected challenges?

Blanck: For us it was very easy because we were in a very successful firm. The issues came a little later, first in 1986 due to the export market collapsing, recession, and then COVID, which was such a difficult time that we reduced our space, from 35 hectares to 25. When you have this situation, you have to adapt. You have to pay your bills, you have to pay to your loans, you have to pay salaries, you have to find your balance. So we reduced the size of the boat to be more efficient. A neighbor took over some land we had on loan.

Blanck: For us it was very easy because we were in a very successful firm. The issues came a little later, first in 1986 due to the export market collapsing, recession, and then COVID, which was such a difficult time that we reduced our space, from 35 hectares to 25. When you have this situation, you have to adapt. You have to pay your bills, you have to pay to your loans, you have to pay salaries, you have to find your balance. So we reduced the size of the boat to be more efficient. A neighbor took over some land we had on loan.

(Philippe and Frédéric Blanck)

GC: Do you and Frédéric have children in line to take over some day?

Blanck: My son works in the vineyards so he’s really interested, motivated. He sweats in the vineyards. Frédéric has a son who is a winemaker in Australia and who has a vineyard there. He’s working for a big company as a viticulturist and with a partner making his own wine where he buys the grapes. But also with the evolution of the price of the land in Alsace, part of the family that is not involved in wine would like to sell it. Every generation we have a new challenge. The challenge for this generation is finding investors and finding young people who are motivated because 50% of the winemakers are over 60 years old. In the next five or 10 years, there will be a complete change in the viticulture in Alsace. I have not yet searched for investors. We have a different point of view than my cousin about the question.. We agreed to find a new patrimonial ground with part of the family and people interested in legacy and transmission. This is a work in progress. The future is open. There are a lot of changes and issues and not just in Alsace. I admire my friend David Ramey of Ramey Wine Cellars in Healdsburg, California, whose children are now co-presidents of the business.

GC: Do you think the coming changes will upset traditions?

Blanck: Sometimes there are options. There’s this flower that when they grow too much, you have to divide them. So like in Burgundy, you have smaller domains. Perhaps this is the solution. People are more interested in money than the generation before. People are sometimes split over traditions. There is always turmoil every 100 years but things always recompose. I’m not very worried about what is the form of it. I’m more interested in how the legacy passes to people. Our sons, some older cousins and their sons are involved in winemaking and viticulture. Everybody is backing up each other. This is what I’m considering as a community. I’m a positive person so my vision of change is different. I am a Christian who is also a Taoist. There is a saying in Chinese culture: “Do the right thing in the right moment.” The future is always open. I believe the key to the future is innovation.

GC: We can still taste that 1993. Have you found Americans becoming more open to aged fine wines from Alsace?

Blanck: We were in Dallas and had a 2007 Pinot Blanc from the Classic range and it was aging very well. Then we had a single vineyard Pinot Blanc from 2008 and it was a Hallelujah wine. You heard the bells ringing. When you get this testimony and people get more aware of that, it’s a good thing.

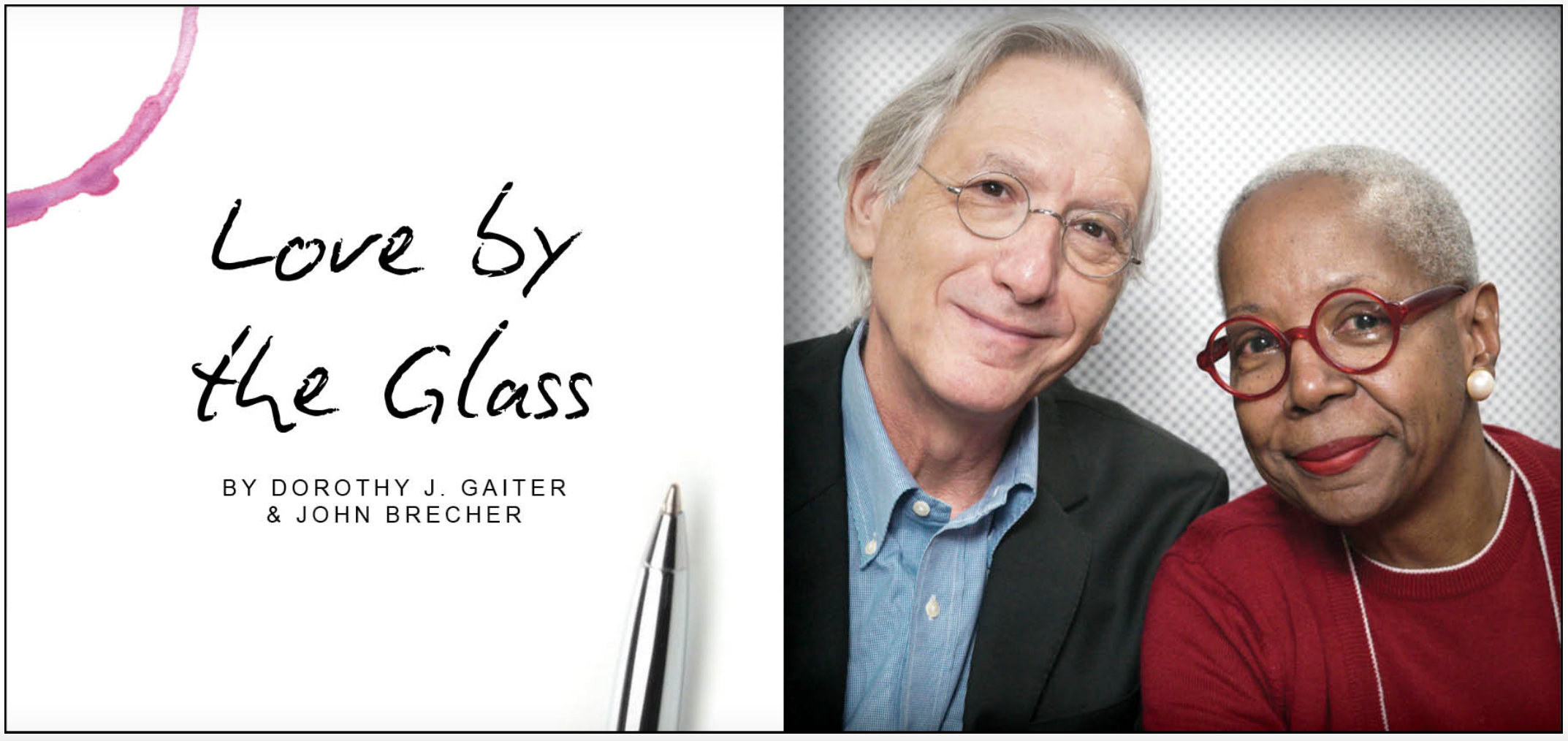

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.