Wine regions need a signature grape. Oregon has Pinot Noir. Argentina, Malbec. Napa has Cabernet Sauvignon. The Finger Lakes region, Riesling. All of these areas make excellent wines from many kinds of grapes, but the signature grape gives consumers a focal point, a place to start their journey. “It’s like a calling card,” as Doug Glorie puts it.

Glorie is president of the Hudson Valley Cabernet Franc Coalition, an eight-year-old group that realized that wines from hybrid grapes like De Chaunac, no matter how well-made, were not the future of a thriving industry because of consumer resistance. So the group took a significant risk on something different.

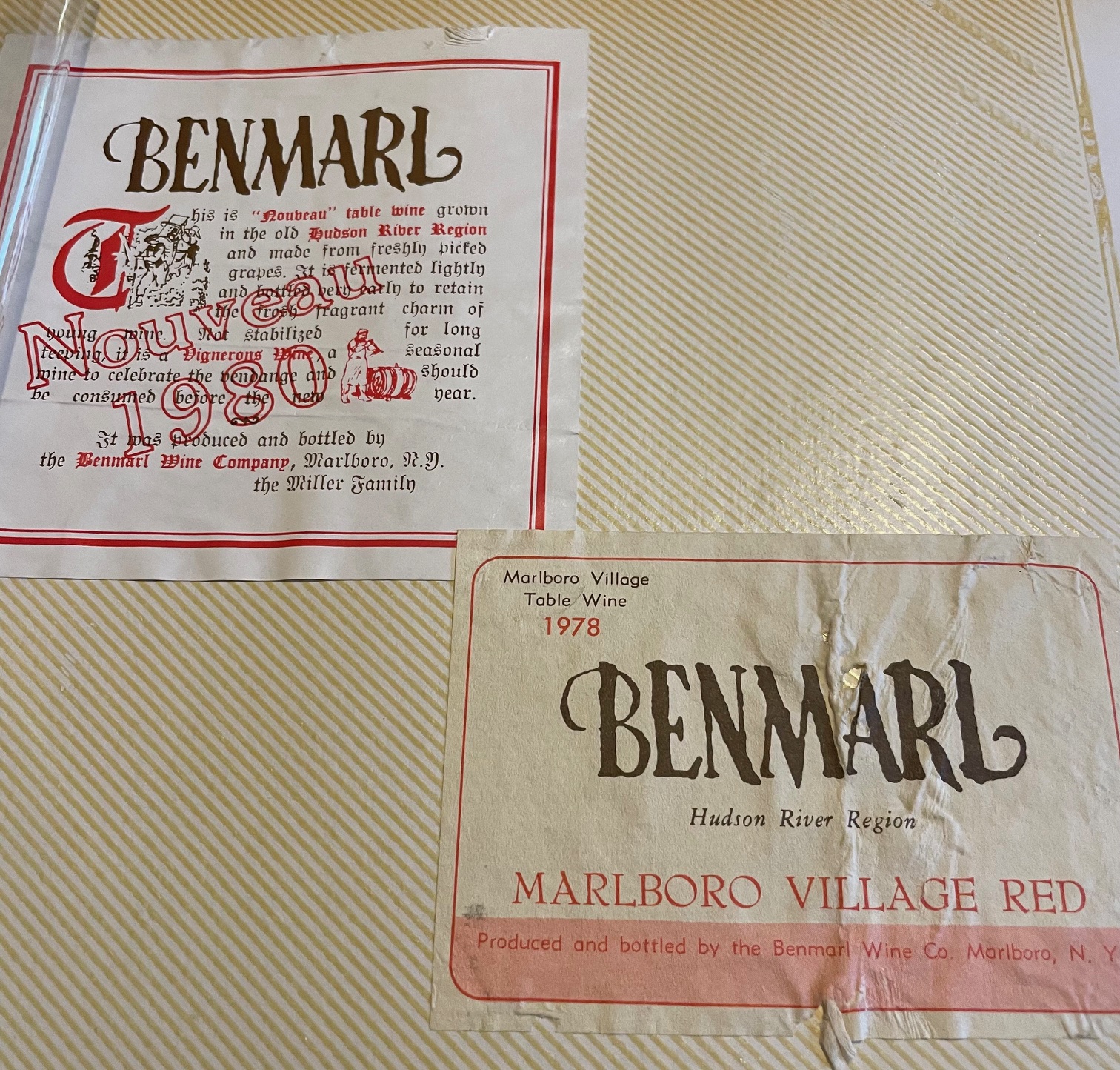

The Hudson Valley American Viticultural Area, north of New York City, includes about 60 wineries, mostly on the west side of the Hudson River, according to the New York Wine & Grape Foundation, which cautions that the figure is from 2021 and may be inaccurate. We had our first wines from there in 1980, both of them from Benmarl Wine Co. in Marlboro. One was “Marlboro Village Red” and the other was simply “Nouveau 1980,” made from “freshly picked grapes,” though the label doesn’t say what variety. For some reason, we believe it was Baco Noir, a French-American hybrid grown in the area.

The Hudson Valley American Viticultural Area, north of New York City, includes about 60 wineries, mostly on the west side of the Hudson River, according to the New York Wine & Grape Foundation, which cautions that the figure is from 2021 and may be inaccurate. We had our first wines from there in 1980, both of them from Benmarl Wine Co. in Marlboro. One was “Marlboro Village Red” and the other was simply “Nouveau 1980,” made from “freshly picked grapes,” though the label doesn’t say what variety. For some reason, we believe it was Baco Noir, a French-American hybrid grown in the area.

As it happens, in 1979, just a year before, Doug Glorie bought land in the region for a farm. He began planting grapes in 1983, but not Cabernet Franc. “We weren’t aware it could grow here, so we were planting hybrids,” he told us. He planted his first Cabernet Franc around 1994. Other wineries got interested, too. When we dropped into Whitecliff Vineyard & Winery in Gardiner in 2009 anonymously after visiting Zoë in college upstate, we tasted through their wines and left with a bottle of Cabernet Franc. Benmarl planted three acres in 2016.

A vitis vinifera, Cabernet Franc is one of the world’s great grapes, of course, a fundamental building block of great Bordeaux and Bordeaux blends around the world. It’s the standout red grape in the Loire region of France, used to make stunning Chinon. We've been fans of Cab Franc from Long Island, N.Y., for many years and have had some outstanding examples from California.

But Cab Franc is likely not associated with a specific U.S. wine region among many consumers, so Doug Glorie, 76, and his wife of 31 years, MaryEllen, realized in 2015 that this meant a wide open lane. The region had been thinking about a signature grape for a while, Doug Glorie told us. “We tried to figure that out early on, probably in the early 2000s, and we were thinking about the term diversity, we have so much diversity. Each winery’s making different kinds of wine from different kinds of grapes and that should be it, a calling card, a way to get people to come to our vineyards and wineries. But it didn’t seem to work. And we tried Seyval Blanc as a white heritage wine, with De Chaunac being the hybrid Hudson Valley heritage red, but that never took off, either.

But Cab Franc is likely not associated with a specific U.S. wine region among many consumers, so Doug Glorie, 76, and his wife of 31 years, MaryEllen, realized in 2015 that this meant a wide open lane. The region had been thinking about a signature grape for a while, Doug Glorie told us. “We tried to figure that out early on, probably in the early 2000s, and we were thinking about the term diversity, we have so much diversity. Each winery’s making different kinds of wine from different kinds of grapes and that should be it, a calling card, a way to get people to come to our vineyards and wineries. But it didn’t seem to work. And we tried Seyval Blanc as a white heritage wine, with De Chaunac being the hybrid Hudson Valley heritage red, but that never took off, either.

(Dottie and MaryEllen and Doug Glorie)

“We want to get recognition. We tried with hybrids, but the real world likes vinifera. So we thought so what are we going to do?”

MaryEllen, now the treasurer of the coalition, discussed this with other winemakers around the state and came back with an answer: Cabernet Franc, a parent grape of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Carménère. They then discussed it with Robert Bedford and Linda Pierro, publishers of the Hudson Valley Wine Magazine, who signed on and now are the vice president and secretary of the coalition, respectively.

“The thing about Cabernet Franc is that it’s widely planted in the area. It does flourish here. It does produce a pretty reliable crop. It has the word Cabernet in it and people like that,” Doug Glorie said. He said that while many vinifera grape varieties, including Cabernet Sauvignon, will not do well in the cool climate of the Hudson River Valley, Cabernet Franc can ripen with fewer days when it is warm enough for ripening, so it’s a solid choice.

They took their idea to local vineyards and wineries and received a positive reception. “The Hudson Valley needs clarity in people’s minds,” Yancey Stanforth-Migliore told us. She is the founder-owner of Whitecliff, along with her husband, Michael Migliore.

They took their idea to local vineyards and wineries and received a positive reception. “The Hudson Valley needs clarity in people’s minds,” Yancey Stanforth-Migliore told us. She is the founder-owner of Whitecliff, along with her husband, Michael Migliore.

(Dottie and Yancey Stanforth-Migliore)

The coalition was formed in 2016. It now has eight members: Benmarl, Fjord, Milea, Millbrook, Quartz Rock, Robibero, Rosina’s and Whitecliff. The Glories sold their farm and winery and its 54 acres in 2020 and the new owners have renamed it Quartz Rock.

Reliable and current statistics on vineyard acreage are hard to come by in New York. The New York Wine & Grape Foundation says there were 446 acres under vine in 2011 in the AVA and that it is conducting a survey of acreage in New York now that will be released in July.

Doug Glorie said their members have about 40 acres of Cabernet Franc and there are probably 10 more among non-members. That’s a drop in the bucket in a worldwide perspective, but Glorie said there might have been one acre in 1990 and he and the other members see this as a virtuous cycle. He said there are bound to be more wineries and wine growers coming to the Hudson Valley. “There’s going to be more of that in the future, people who have money, people who want to participate in this journey of making wine and growing grapes. They’re going to say, well, what should I grow, what should I be, what is useful, what will I be successful with? And they see other wineries being successful with that. And they see this happening and they say I want to be a part of this. It builds over time.”

Like some of the stricter wine regions around the world, the coalition has rigorous rules. The wine has to be 75% Cabernet Franc from the AVA. At least 85% of all of the grapes (including other varieties) must be from the region. The rest of the grapes have to be from New York State. And once a year, there’s a blind tasting to see who can put the black hawk – the symbol of the coalition – on the neck of the bottle. Chianti Classico has another bird to show that the wine met its standards, the black rooster.

“If people want to apply that black hawk seal to their bottle of Cabernet Franc, we say, bring that to our meeting,” Doug Glorie told us. “Usually it’s finished or almost finished, could be out of the barrel or ready to release. And we pass it around with a bag over it among the membership and the officers and we taste them blind. We’re not over-critical, we’re pass/fail. We taste them to make sure they are all high-caliber, there’s no drawbacks to the wine. And we have had that. And we’ll say, you know, Joe, we think that wine is a little bit suspect and we’ll talk about it and that winery will say, you know, I’m not going to put that sticker on it.”

We tasted through wines of all eight members at an event recently at Benmarl, which made us smile since it closed a circle for us. One word all of the producers use about Cabernet Franc is “versatile” and that was certainly on display. Fjord served a juicy rosé and Robibero even makes a white with some bite. We had read about white Cabernet Franc, but had never had one. Quartz Rock poured a beautifully well-structured barrel sample.

We have always liked Cab Franc because of its distinctive pepperiness, vitality, and one of its markers, hints of pencil shavings. It can also sometimes have significant herbalness, which can be fine in small doses. These wines were quite varied, but thoughtful and proud. After all these years, we still very much liked the Whitecliff, which has a special purity.

To be sure, the Hudson Valley wineries are still finding their footing with Cab Franc, but this isn’t unusual. We’ve seen Oregon Pinot Noir change dynamically, for instance, since we first starting drinking it more than 40 years ago. When we first wrote a column about Cab Franc in 1999 in the Wall Street Journal, we had trouble finding enough made in the U.S. to taste. Our favorites back then included classics, such as Lang & Reed, Longoria, Consentino and Robert Sinskey. By 2022, we wrote in this publication “The Red Wave is Here: It’s Cabernet Franc” and its price per ton exceeded that of Cabernet Sauvignon, in Napa. Some note-worthy newcomers we’ve discovered include single vineyard ones from T. Berkley Wines in Calistoga.

“We want to expose more people to the grape and that the Hudson Valley can grow it,” Doug Glorie told us. “That’s the whole idea of the coalition, to expose the grape, expose the wineries, get people to come to our tasting rooms, try the Cab Franc and while you’re there, maybe that’s not your wine, maybe you will like a hybrid better, or another vinifera at that winery, and that will enable more sales at that winery. Come to our winery, then you can see the breadth of other wine we make here.”

“We want to expose more people to the grape and that the Hudson Valley can grow it,” Doug Glorie told us. “That’s the whole idea of the coalition, to expose the grape, expose the wineries, get people to come to our tasting rooms, try the Cab Franc and while you’re there, maybe that’s not your wine, maybe you will like a hybrid better, or another vinifera at that winery, and that will enable more sales at that winery. Come to our winery, then you can see the breadth of other wine we make here.”

(Dottie and Doug Glorie)

All this said, we had gone to an elegant restaurant in Poughkeepsie the night before the Cab Franc tasting and there was not a single local wine on the list, even though it had a sign in the window pushing local products. We asked Glorie if it is difficult to get the wines into New York wine stores and restaurants. He paused for a while and finally said, “Absolutely. It’s really difficult.”

It’s not just New York. In happens all over the U.S. Here’s a good story from Henna Bakshi, one of the fellows at the Wine Writers Symposium this year, on the lack of wines from the state of Georgia on the wine lists of restaurants in Atlanta.

So next time you do see a local wine in your store or a restaurant, think about those people in the Hudson Valley Cabernet Franc Coalition, who have a vision and are putting a lot on the line to fulfill it. They deserve our support.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.