David Ramey has seen a lot of change since he graduated UC Davis in 1979. Ramey learned his craft working in Bordeaux for the Moueix family of Chateau Pétrus and then at the high volume Australian winery Lindemans. While Napa and Sonoma have seen stylistic changes over the years, Ramey is known for his consistently well-balanced wines. "Unlike many of his California contemporaries, David Ramey makes wines of restraint and vibrancy." Jay McInerney wrote in The Wall Street Journal.

Grape Collective talks to Ramey about the changes he has seen over the years and the challenges for young California winemakers today.

Lisa Denning: Can you tell us a little bit about your background, and how you ended up in wine?

Lisa Denning: Can you tell us a little bit about your background, and how you ended up in wine?

David Ramey: I have a highly technical degree in American literature from UC Santa Cruz and when I got out, I was a waiter in a Sicilian restaurant in Los Altos. We waited on ex-49er football players like John Brodie. And then I thought I was going to teach English in Columbia for a couple of years. And during the long drive between Mexicali and Hermosillo — I was by myself in a '71 Toyota Hilux pickup truck with no radio — I was thinking, "Well, what am I gonna be, what am I gonna do when I'm done with this?" And it was, in French you would call it a coup de foudre, a lightning bolt, it was like an inspiration.

Well, why not make wine? In fairness, I had been visiting wineries, reading wine books, tasting wine and I thought, "Well, okay, but I can't do that. You have to go to the University of California, Davis for that. That's just for sons and daughters of industry, like Mike Martini." And then I'm driving along, and you know, 10 miles later I was like, "That's not true. It's the University of California. My folks pay taxes for it. Hell, I pay taxes for it." I continued on and I was staying with a family at the time in León, Guanajuato, in Central Mexico, and I all but turned around and came back.

And two weeks later I was in Chem 1A at San Jose State. It took four and a half years from Chem 1A through the Master of Science in oenology from UC Davis. But that's okay, because I wasn't doing anything else. Thank God that coup de foudre happened, because otherwise I don't know what I would've done with my life. So, yeah, the only thing I've ever done as a grown up is make wine.

All of my classmates that came out of Davis in '78, '79, there were about 30 of us — John Kongsgaard, Cathy Corison, David Graves, Dick Ward — we all had undergraduate degrees in political science, literature, history, philosophy, psychology. We got out of school and realized that we didn't want to get an MBA. That wasn't even a thing then. We didn't want to be doctors, didn't want to be lawyers. But making wine, "Wow, that's cool!"

So we all ended up at Davis at the same time but I knew that I wanted to work overseas, so I did that. I worked with Christian Moueix in Pomerol, Bordeaux and I worked in Australia for Lindeman's Karadoc Winery, a big factory. And then when I came back to California, I was fortunate to be able to get a job as Zelma Long's assistant at Simi Winery. It was 1980 and everybody else got full-charge winemaking jobs, but I realized we didn't really know how to make wine and that I needed some experience. Zelma and I worked together for five years and did some really good work with oxidized juice, brown juice and white wine production with lees contact, skin contact and temperature variation which I published a paper on. Then I was asked to replace Merry Edwards at Matanzas Creek, so I did that for five years, and kind of grew that brand.

Then Christian asked me to come back to Bordeaux in '89, and I was affianced to my wife and business partner Carla at the time. We were married in France. But then he said, "It's not time to work together. Get a job, and we'll see." So the job I took was back in the US at Chalk Hill and, for six years, I traveled a lot, and changed the style and quality of the Chalk Hill Wines.

Next I went over the Mayacamas mountains to the Napa Valley and I helped build Christian's Dominus Winery. I was actually sort of in charge of the construction. I was the General Manager and Winemaker there. After a little while I met Leslie Rudd, and agreed to help him turn the Girard Winery into Rudd Estate. So that was the last job that I had. And I left Les in '02.

But the thing about going to work for Christian was, I said, "Well, Christian you know, you don't make any white wine," and he said, "Well, if you want to make a little Chardonnay on the side, that's okay." A light bulb went off. I knew Larry Hyde from Matanzas Creek and I bought his Semillon to go into the Matanzas Sauvignon Blanc. And he found a little Chardonnay for me. And that's how we started Ramey Wine Cellars with 260 cases of Hyde Vineyard Chardonnay, 1996 vintage. Sold in '98, cause we do a long time, 20 months, in barrel on the lees.

And we started in just six states, and one of them was right here in New York, with Michael Skurnik Imports. And here we are almost 20 years later, still with them.

(Photo: Camomile cover crop grows at the base of the Ritchie Vineyard Chardonnay vines, planted in 1972.)

How did your experience in Bordeaux influence your winemaking?

Tremendously. I would say in two ways, with red wine, with the Cabernet complex: Cabernet, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec. In Bordeaux you don't add tartaric acid to those, because as Jean-Claude Berrouet, the long time oenologist for Moueix told me, "Tannin and acid are contrapuntal." and so as the tannin goes up, that's Cabernet, the acid must come down. And then as the tannin goes down, the acid goes up, that's Pinot Noir, which is sort of the white wine of reds, because there is a more feeble phenolic structure, tannic structure, and acidity plays a more prominent role.

At the time, UC Davis was telling everybody that low pH was tremendously important, and winemakers were acidifying their red wines a lot. I left Simi where we were doing that and went to Matanzas where I just stopped acidifying, and that's why really, the Matanzas Creek Merlots were so good. That was a little unusual. So that's one instance of French influence, and then, traditionally in France — when I worked with the Moueix organization in '79 — they didn't inoculate, they used native yeast. So I came back to California in '89 and was committed to trying native yeast, wild yeast fermentations, which was really radical in California then although Paul Draper had been doing it for decades. I found that it works and so I've been using native yeast for a quarter of a century now.

So I would say those would be the two influences, and the third thing is the realization of wine as a natural product. I sometimes joke that nature has been making wine for 6,000 years before oenologists showed up. At Ramey, we use all native yeast, native bacteria, and we don't own a filter. So we really do let nature make the wine. And that, I would say, I got that from the centuries of tradition in France that I was fortunate enough to be able to be part of for a while.

If you were starting out today, would you be able to start a winery?

Well, I can't say that I couldn't start a winery today, because so many people are doing it. On the other hand, I'm glad that I don't have to, because so many people are doing it. There are increasing numbers of labels every year, and the competition is deafening, frankly. So many voices clamoring for attention and not only on the wine side, but on the press side too. 25 years ago there was a handful of critical voices in the wine world that mattered. And now, there's a proliferation of voices, and mostly it's a positive thing, but it also can be confusing and deafening. So yes, I could, but it's much more complex now than it used to be.

Since you started your winery, what kind of changes have you seen in Sonoma and in Napa?

I would say that on the Chardonnay side, which is half of our production, the significant changes are the widespread adoption of Burgundian technique — barrel fermentation, sur lie aging and malolactic fermentation — along with the march to the coast. You just don't find a lot of Chardonnay in Rutherford anymore. And Napa Valley has become close to a Cabernet monopole. In Sonoma, a lot of Chardonnay is grown in the Russian River and the Sonoma Coast area now. And people have realized that the cooler climate of the marine-influenced coast gives a fresher, livelier Chardonnay product. That's a big change that we as an industry have discovered over the past 30 to 40 years.

What advice would you give to a young winemaker today?

Well is this winemaker coming from left field, or is this a winemaker fresh out of Davis, or Fresno, or Cornell with a degree in oenology?

Someone like you, who came out of Davis.

If I were him or her, I would go work with somebody who knew what they were doing for a while and then you just see where your career takes you. I'm really fortunate we had the opportunity to start our own brand which we've grown into a substantial business but not every winemaker is cut out for that.

There are a lot of analogies between winemaking and cheffing at restaurants. And there's a difference between making wine and running a winery. There are a lot of business aspects that need to be successfully managed. It's the same thing with chefs, some are tremendously creative, and can plate food beautifully, but when it comes to managing staff, and insurance, and rent, and the whole business aspect, they're maybe not cut out to be restaurant owners. You know, when I was at Davis, and I've told them this, nobody made me take Business 1A. I didn't learn the difference between an income statement and a balance sheet at Davis but I should have, because every winemaker is responsible for that ultimately. That's what I would say.

What is your philosophy of winemaking?

First, wine's supposed to taste delicious! That's it. Now, that said, for us it means working with nature to let nature craft the wine, as opposed to manipulating it from the outside with additives. We want it to taste delicious, but we're purists, we're classicists. So we let nature do that but we monitor the process closely and we intervene a little bit where we need to, if we need to.

So sometimes an anology I use is, we're on the surfboard and we're coming into shore, and we're making little corrections to the surfboard on where the wave is pushing us to shore. But we never lose sight of the fact that it's the wave that's pushing the board to the shore, not us. And that's a fundamental difference between that approach and the food technologist approach, sort of the additive, making the wine from the outside in, instead of letting nature make the wine from the inside out. And again, I'll mention Paul Draper, who was one of the great gentlemen of the wine world, still is, he retired but he's still alive; he's 80, or 81 now. He used to say, "The grape is the only thing in nature that contains everything it needs to make its finished product." And that's a really interesting fact when you think about it.

Can you talk about your Cabernet Sauvignon and what makes it special?

It's a number of things. Picking at the right time where the tannins are mature and supple but before you get porty, jammy, raisiny flavors. If I see a few tiny raisins, that's fine, if I see more than that, I've waited too long. If I don't see any, I might not have waited long enough. Gentle handling of the fruit.

In Bordeaux, they classify red wine, which is really all they care about, into two kinds, vin de garde, and vin de consomation. Vin de garde is one to keep, guard, and vin de consomation is supermarket wine, it's wine to consume. And the difference is the amount of extraction that you do. So if you make a vin de consomation, you drain early, you limit extraction. But if you make a vin de garde, the tradition is about three weeks. So we do that. We make vin de garde and our wines always show better at 10, 12 and 15 years old than they do when they're fresh.

The next thing is barreling down, it used to be called barreling hot. We drain one day, and we go to barrels the next day with the lees. That lees is important. There's not as much lees in red wine as in white wine that's fermented in a barrel but there is some. And that's important texturally for the wine. The next thing, blending early. When you blend early, the wine comes into harmony during the élevage. You know, that's a great word that the French use. They elevate the wine in barrels. It's the same word that they use for students. A student is an élève because they are being elevated during their schooling.

And so we school the wine properly, like having good parents raise you properly. And since we don't acidify, the wine has its own natural harmony. It's unfortunate that unfined and unfiltered has entered the wine lexicon, because these are two completely different things. Fining with traditional fining agents like fresh egg white for red wine is a traditional artisanal part of making fine wine, going back hundreds of years. We fine all of our Cabernet with egg white, and then we don't filter it. We don't own a filter. So all those classical techniques go into making a wine that has built itself from the inside out rather than having the wine maker poke at it from the outside in.

Are you organic?

Well as organic as makes sense to be. No, we don't seek to become certified organic, because one example is that to be certified organic, it has to be mined sulfur as opposed to chemically produced sulfur. That costs 10 times as much. It doesn't make sense. When we bought our vineyard, one of the first things we did was to eliminate Roundup in the vine rows. So we're as organic as it makes sense to be, but not slavishly so.

There seem to be two styles of wines being made in California these days, the big, powerful, high-alcohol wines and then the more food friendly, lower-alcohol style. Where do your wines fit in?

We've always been in the middle and have a pretty consistent stylistic vision for all of our wines. Now that we've bought 75 acres on West Side Road, a mile south of Rochioli and across the street from Williams Selyem, we're starting to make a Russian River Valley Pinot Noir. And stylistically, it's in between the sort of, really cola, Slurpee type of Pinot Noir, and the extreme coastal, austere, hair shirt Pinot Noir. I would say it's the same thing with our Chardonnays and with our Cabernets.

You know in France, the great vintages have always been the warm vintages, which there are more of now, with global warming. But in a warm vintage you get higher sugar at harvest, and you get more alcohol in the wine. So good white burgundy will reach 15% alcohol naturally in a ripe year. That's an extreme, but it exists. The last couple of Leflaives I analyzed, they happened to be from the '06 vintage, there were two Premiere Cru Pulignys, I think a Clavoillon and a Pucelles. And one was 14.65, and the other was 14.72 alcohol.

And then I would say, with very few exceptions, when faced with a 12.5 percent alcohol vintage in Burgundy or Bordeaux, they chaptalize to 13.5 or 13.8. To say that there is this sort of anti-Robert Parker perspective of, "We're gonna make mean, lean, low-alcohol wines," I don't agree with it. On the other hand, some of the 16% Napa Cabernets with residual sugar, that's not our style either. We're classicists, so we make honest wine with native yeast, native bacteria, and we don't own a filter. Everything we do is unfiltered.

We're making Neo Burgundian, or Neo-Bordelais, but with the blessedness of California's climate. I mean, it doesn't rain for six or eight months of the year. How good is that? We had Jeremy Seysses doing a tasting for us once, and he said, "You guys that are sorting your grapes, you're idiots," he didn't say that, but that's basically what he said. "Your grapes are beautiful, they're perfect! You don't need to sort your grapes!" So that's the climate with which, I think if we take hundreds of years of French tradition of making wine and apply it to our grapes in California, we get this glorious product.

Let's talk a little bit about corks and other closures. In 2009, you started experimenting with Diam corks. What have you learned since then?

We do constant experimentation on everything, including closures. We've done experiments with screw caps, both the tin liner, and the Saranex liner. The tin liners are supposed to block all the oxygen and the Saranex liners are supposed to let a little bit through. We've tried plastic corks and Noma cork. In '09 when we did the experiment with Diam, we had no expectations. It takes a while, under different closures, to express itself. Unless it's a really bad closure, you don't see that in 12 months. It takes a number of years for it to develop. So every year, before we bottle any particular wine, we open up all the preceding bottlings that we did of that particular wine. We analyze them, we taste them, and we say, "Well, what did we do right? What did we do wrong?" And we try to make a little improvement.

In 2014 it was the Ritchie Vineyard Chardonnay that we'd done the Diam experiment on. Wow! It was clear that the Diam was a better wine. So we did more experiments, and very quickly we realized that this technical cork was the way to go.

The raw cork plug manufacturers want to say that the only issue with raw cork is TCA, trichloroanisole, which makes corked bottles and makes the wine smell like damp newspapers in the cellar; musty, moldy. It's very distinctive, especially at higher quantities. The insidious thing is, at very low quantities where it's not distinctive, it does what we call scalping. It scalps the aroma of the wine. So the wine isn't expressing itself as well as it could and if you don't know the wine, you just think, "Oh well, that wine's okay, but it's not particularly good."

But that's only half of the issue. The other half is OTR, oxygen transmission rate. And, for example, we just had lunch at The Modern at The Museum of Modern Art. They have our Hyde Vineyard Chardonnay and half bottles on the list. We had a guest so we ordered two bottles and the first one was a little more mature than I had hoped. It was a little more golden and a little more nutty in the aroma. We ordered a second bottle, and it was perfect. It was just like we bottled it yesterday, or six months ago.

And that's the significant fault of what I now call raw cork plugs. Diam solves that issue by standardizing the OTR. It doesn't mean that there's not going to be a better mousetrap produced by somebody else someday. We have experiments going this coming bottling and it doesn't mean that Diam is going to improve everything. But right now, we think it's the best solution.

Tell us about your second line of wines, the more affordable Sidebar Wines.

Sidebar, in law, is when the judge calls opposing counsel to the bench, out of hearing of the jury, and they have a little sidebar. In literature, if you are reading an annotated Shakespeare, there's a little down the side of the page with notes. Or in our business, in restaurants or bars, you might have the main bar, and then you've got a little sidebar over there for overflow, or for a special product. So Sidebar's our second brand, and it's kind of a fun brand. It doesn't mean that we don't make it with native yeast and sur lie aging, and it's unfiltered, but it's varieties that Ramey as a brand does not deal with. Ramey makes Chardonnay, Cabernet, Syrah, and a little Pinot Noir now.

But Sidebar can do anything. It can do Sauvignon Blanc from High Valley in Lake County or Sauvignon Blanc from Kent Ritchie's 42 year old vines in the Russian River. It can do Kerner from Lodi, or 125 year old red field blend from Russian River. So lots of interesting possibilities with Sidebar in a little less traditional package and a somewhat different price point.

And how is it that you are able to have them at a much lower price point than the Ramey Cellar Wines?

The lower price of the grapes. Napa Valley Cabernet costs a lot of money as does Sonoma County, Russian River Valley Chardonnay and Pinot Noir.

I understand that you bought some property in the Russian River Valley, and that you would like to build a visitor center and tasting room there. Can you tell us the status of this project?

It's been a long process but we were approved. December 27th will mark five years since we bought the property. We have done 10 or 12 studies and the planning commission did approve our project, but there are some people who have retired to wine country, because well, yeah, it's nice. Nice climate, nice environment, nice restaurants, but they think there's too many wineries, too many hotels.

So they're sort of anti-winery, anti-vineyard, anti-tourism, even though they chose to retire to wine country and bought an ag zoned parcel and built a Mc-mansion on it. So this is what's happening in Sonoma County now. Napa is also feeling these growing pains and Paso Robles is and certainly Santa Barbara County is. People are trying to turn ag zoned land into rural residential, and those are two different zonings. And I would say that if you want to do that, you need to get the county supervisors to change the zoning in the general plan, which is redone every 20 years. But in the meantime, they're trying on an ad-hoc basis to deny property owners their rights because wineries are commercializing rural areas and impacting rural character.

But as John Bucher, one of our Pinot Noir growers and neighbor, asked one of our supervisors, "But what defines rural character? Is it agriculture? Or is it houses?" And so this is where we are right now. The project has been appealed to the board of supervisors and we're waiting for that hearing. I anticipate that the planning commission's ruling will be upheld. But, we'll just see what happens.

We wish you luck with that.

Thank you very much. It has been a more dispiriting experience than we anticipated.

What do you like to drink when you're not drinking your own wine?

My wife would be the first to tell you that Brunello is a recent love. I have way more Brunello than I should. I started buying with '06 and '07 vintages most recently, and then I bought a lot of the '10s and a lot of the '12s. I love Alsatian style Gewürztraminer. If it is dry, we buy a case of Navarro dry Anderson Valley Gewürztraminer every year, and then various Alsatian ones. We like un-oaked Italian whites: Vermentino, Verdicchio, Arneis, Kerner from Alto Adige, Fiano di Avellino, Gavi. We have all those wines in the cellar.

(Photo, Lisa Denning and daughter Colette visiting with Cameron Frey, VP Winemaking, at the Ramey Cellars red wine production facility in Healdsburg)

And if you were stranded on a remote island, what would you bring with you for a book, a movie, and a bottle of wine?

Oh, wow. A book, well since I was an American lit major, I'm tempted to say an Ernest Hemingway novel, but all American literature starts with one book, Huckleberry Finn. I'd have to think about that. But that could well be it, Huckleberry Finn.

And then a movie. You know I had the pleasure of consulting for a while for Francis Ford Coppola, for his Rutherford brand. Francis cooked me lunch one day, which was, I'm not afraid to say it, a high point of my life — not the high point, but a high point. Apocalypse Now could be one, Godfather I is one, Godfather II is one. Every year my son Alan and I, and our son-in-law Ivan watch The Godfather trilogy, and Alan, who's now 25, said this time that it's probably the fourth time he's seen it and he said, "Every time I see new stuff," so I'm gonna say Godfather I & II. I'm gonna stretch it a little bit.

Oh, one bottle of wine. Usually I'm asked for red and white and the answer used to be a dry Alsatian Gewürztraminer and a Châteauneuf-du-Pape, like a Henri Bonneau, or a Beaucastel. But now, if I had to say, I would probably say a Valdicava Brunello from a good vintage. And then some Ramey Chardonnay for my wife, cause we would be there together.

I have one last question for you. Did you take Dorothy Gaiter's advice, and go to Jazz Standard and listen to jazz while drinking your Sidebar Kerner?

I absolutely did. When we were here the third week in October for the Wine Spectator tasting at the Marriott, my son Alan was with me, and our last night in town, after dinner, we went to Jazz Standard and ordered a bottle of Kerner.

You have experienced a lot of change in the wine business over the last 30 years.

You know what I would say, and we were just talking about this with Ray Isle at lunch yesterday. It's the tremendous interest that's developed in America for wine over the last 30 years. We love it, we appreciate it but at the same time, it creates a lot of noise and confusion. What I would say is, the way I learned about wine, other than learning about chemistry at Davis, and other than learning about cellar techniques in the cellars of France, the way I learned about wine is  buying and tasting, and blind tasting.

buying and tasting, and blind tasting.

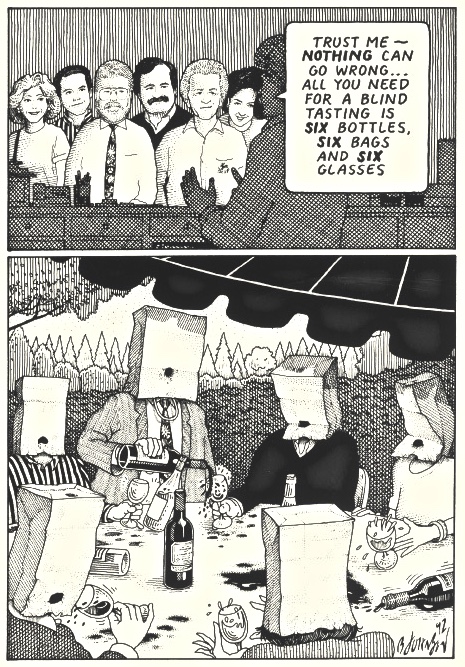

There's that great Bob Johnson cartoon with the retailer telling the guy, "Nothing can go wrong. All you need for a blind tasting is 6 bottles, 6 bags and 6 glasses" and then the people all have the bags on their heads, and the wines are all over the place. Blind tasting with like-minded colleagues is how I learned about wine, how I learned to identify what aldehyde was in a wine, what H2S was in a wine, rotten egg smell, what gunflint, which is disulfide, is in a wine. I would just encourage people to do that and Grape Collective is a great spot to choose your wines because the staff here really knows what they're doing.

Read more from Lisa Denning on Grape Collective and on her blog, The Wine Chef.