Sometimes you just fall in love with a wine, right? If it’s a magnum and it’s a Burgundy, that helps, but we’d guess most wine lovers remember a bottle – or two, or three – that they simply fell for, regardless of price or pedigree. That happened to us recently and here’s the story, which, like any good love story, has some angst in the middle but ultimately a happy ending.

We have attended few tastings since the pandemic began. Actually, we haven’t done much of anything since the pandemic began. So we were very happy to be invited to a tasting of the wines of Bouchard Père & Fils with its cellarmaster, Frédéric Weber, whom we’d met before and found to be charming and knowledgeable. Bouchard is one of Burgundy’s oldest and most important winegrowers, producers and merchant houses. Headquartered in Beaune, it is a name from the Côte d’Or we have trusted for a long time. What’s more, the dinner and tasting was at New York’s Keens Steakhouse, famous for its giant steaks and chops.

The dinner featured some of Bouchard’s most famous wines: We tasted Le Corton 2013 and 2017 and Corton-Charlemagne 2015 and 2017, all in magnum and all exquisite. They are very special, Grand Cru.

The dinner featured some of Bouchard’s most famous wines: We tasted Le Corton 2013 and 2017 and Corton-Charlemagne 2015 and 2017, all in magnum and all exquisite. They are very special, Grand Cru.

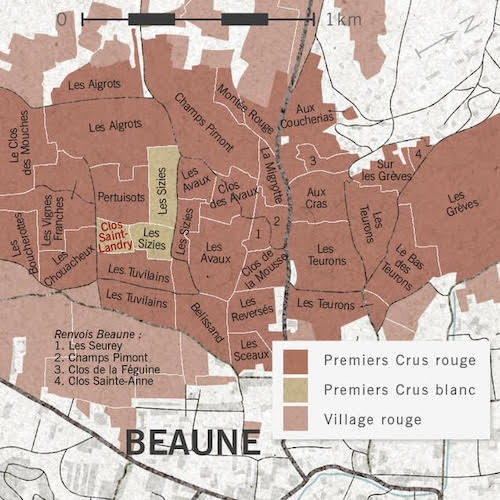

But the first still wine of the night – almost like the warm-up act – was the one we couldn’t shake. It was Clos Saint-Landry 2017 Monopole, a Premier Cru, both luscious and vibrant. Weber had explained that, as a Monopole, it’s from an appellation that belongs exclusively to Bouchard, which is unusual in fragmented Burgundy. Even large Bouchard only has two. Weber also explained that Clos Saint-Landry is the oldest site of Chardonnay in the region and surrounded by Pinot Noir (you can see where it is on the map). Chardonnay has been grown in this spot since at least the 13th century.

Throughout the night, even with Dottie’s giant T-bone, we couldn’t stop whispering to each other about this wine. It haunted us, as a good Burgundy should. We wondered how it would taste as it opened, with air and warmth, sipped slowly, our sole entertainment for the night. We wished that all Chardonnay-based wines could taste at least a little like this: elegant, restrained, balanced.

The next day, as a surprise for Dottie, John went to wine-searcher.com, assuming he could not buy the wine and, if he could, that it would be far out of our price range. Fortunately, he was wrong. He could only find the 2017 in magnum and it cost $120 (with free delivery!). That is a hefty sum, for sure, but not outrageous for a double-size bottle of such anticipated bliss.

Dottie was delighted, of course, but we did have some concerns. We’ve all had that experience when we try a wine on vacation or at a restaurant or at a tasting and then have it again at home and it’s not as good. Was it the moment speaking or the wine? We’d surely like this wine – we’ve had a soft spot for Burgundy for a very long time -- but would we love it? Were we asking too much?

In the days before the wine was delivered, we got back in touch with Weber to ask more questions about the wine. Typical of fine Burgundy vineyards, it has quite a history. “Before it was bequeathed the appellation of Clos Saint-Landry, this vineyard operated under the title of Tiélandry, meaning the estate of a certain Landry. Then it was owned by the Abbey of Maizières before it was purchased by Antoine Philibert Joseph Bouchard in 1791 after the French Revolution. Since then, Bouchard Père & Fils has retained the monopole of this white Premier Cru,” Weber wrote us by email. The Joseph Henriot family of Champagne makers purchased Bouchard Père & Fils in 1995.

In the days before the wine was delivered, we got back in touch with Weber to ask more questions about the wine. Typical of fine Burgundy vineyards, it has quite a history. “Before it was bequeathed the appellation of Clos Saint-Landry, this vineyard operated under the title of Tiélandry, meaning the estate of a certain Landry. Then it was owned by the Abbey of Maizières before it was purchased by Antoine Philibert Joseph Bouchard in 1791 after the French Revolution. Since then, Bouchard Père & Fils has retained the monopole of this white Premier Cru,” Weber wrote us by email. The Joseph Henriot family of Champagne makers purchased Bouchard Père & Fils in 1995.

Bouchard’s press materials on this wine said the site had been “preciously kept” and we asked what that means. Weber responded: “First, it has been kept from erosion and protected by a stone wall, which gives the name Clos in French. Second, it has been farmed organically since 2015 in order to preserve and achieve the most accurate expression of the terroir. Last, it is cared for by the same winegrower (Marc) for more than a decade who knows each vine and parcel very well and can make appropriate decisions based on his experience. A part of it has been torn off in 2017, left fallow for three years (to rest and re-nourish the soils) and replanted in 2020.”

We asked how the winegrowing, winemaking, geography and soil types of the Premier Cru Saint-Landry differ from Grand Cru Corton-Charlemagne. “Clos Saint Landry is a flat area where Corton-Charlemagne is on the hill,” he wrote us. When we were starting out in wine, we’d read that centuries ago monks observed the difference in the quality of wines from grapes they had planted in certain locations. Those on hills tended to be of higher quality and thus more expensive. “Clos Saint-Landry achieves early maturity while Corton-Charlemagne reaches maturity later due to east exposure and windy conditions. In both case, soils are predominantly white and yellow marl – very suited to Chardonnay,” Weber added.

Is the Clos Saint-Landry meant to drink younger? “Younger than Corton-Charlemagne, yes. Ageing potential varies with vintage but it can easily go 5-7 years,” Weber responded.

The Clos Saint-Landry vineyard is only about 5 acres. Weber said it produces 10,000 to 12,000 bottles a year. Of those, maybe 500 bottles are exported to the U.S. We felt very lucky to have bought this wine so easily. And now we had all of the background. It did seem to put a lot of weight, a great deal of expectation, on this bottle, though. Could it meet our hopes?

Sometimes we prefer a fine white straight from the wine closet – at cellar temperature – but in this case we refrigerated our big bottle. Our feeling was that it would warm up once we took it out and we had plenty of time and wine to try it at various temperatures.

We opened it at 6 p.m. to watch the sunset. We’d forgotten how much fun it is to handle and pour a magnum of just about anything. It’s so regal. Many years ago, our friend Chip Cassidy of Crown Liquors in Miami used to sell magnums of Domaine Chandon from Napa as a loss leader for $19.99. We always enjoyed Chandon as a house bubbly, but in magnum it became something larger, and not only the size of the bottle. It became an event. We opened one whenever we needed a giant hug.

We opened it at 6 p.m. to watch the sunset. We’d forgotten how much fun it is to handle and pour a magnum of just about anything. It’s so regal. Many years ago, our friend Chip Cassidy of Crown Liquors in Miami used to sell magnums of Domaine Chandon from Napa as a loss leader for $19.99. We always enjoyed Chandon as a house bubbly, but in magnum it became something larger, and not only the size of the bottle. It became an event. We opened one whenever we needed a giant hug.

So in this case, the first step of the wine tasting was not looking at the wine – it was simply looking at the bottle. Then we opened and poured. The nose was filled with minerals and a kind of Burgundy light sourness that, to us, gives it a sense of place. It hit us in the back of the jaw with its abundant acidity. The fruit, acidity and oak were in balance, with great precision.

We talked about how the wine seemed to us to be a perfect age. It was not better a year ago and wouldn’t be better next year – not that it won’t be delicious for a few years, but we don’t think it would improve with age. At five years old now, we felt it was at its peak of flavor and depth. The combination of weight, vibrancy and nuance lined up at this moment. It was a white wine of real grip, with layers of taste that required small sips to try to appreciate.

At 6:30, with air and warmth, the wine had not changed substantially, but was opening and softening a bit. As the acidity became more linear, the wine became more luscious, with all sorts of citrus fruits on the ascendency. The finish became even longer and more cloud-like, leaving more of a sense than a taste.

We drank the wine throughout the night and it continued to open and become more relaxed, which made it a slightly different wine, more charming, vulnerable like a sweet embrace. With shrimp thermidor and sautéed mushrooms, broccoli and garlic, it pulled off that Burgundy miracle: It complemented every bite and yet never allowed itself to get lost in the flavors of the meal.

We put the wine back in the refrigerator for a few minutes after about an hour for a quick chill. After two hours, there was even less of a taste of oak and, interestingly, a sensation of mint, clean and fresh. And there was more citrus as the wine continued to open.

We did not finish the magnum in one night – we are not as young as we once were – so we pumped it and had it the next day. It tasted very much like it did when we put it away the night before.

Of all the notes we took on this wine, the most important to us was simply this: “Not obvious.” In a world where so many wines are easy to describe, with tastes that announce themselves in capital letters, this Burgundy required our attention to truly appreciate its wonder and complexity. And that means we had to put down the damn phone, turn off the computer, set the oven to warm and let the wine take us somewhere. Ultimately, isn’t that what a truly special wine should do?

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett