Colorado is much in the news these days. Pro football Hall of Famer Deion Sanders is turning heads as head football coach at the University of Colorado. Colorado got its first Michelin Guide and five restaurants with a star. The winery we’re writing about here, The Ordinary Fellow, is in Colorado and has wine on the lists of two of those five, Bruto and The Wolf’s Tailor.

“That ain’t bad,” Ben Parsons, The Ordinary Fellow’s winemaker and owner, told us when we called to discuss the wines that were sent us a month before the Michelin announcement. Parsons, 47, who is from England, and says “whilst” instead of “while,” was clearly being charmingly colloquial and humble. He had just recently driven to the vineyards he sources from and works, Hawks’ Nest Vineyard at 6,800 feet and Box Bar Vineyard on the slopes of a mountain that overlooks Mesa Verde National Park, and through Telluride with its movie-set vibe and mountain peaks. “I was thinking. It’s a beautiful state. This is so beautiful. There are worse places to live,” he said, laughing. “I’m really happy with what we have achieved.”

“That ain’t bad,” Ben Parsons, The Ordinary Fellow’s winemaker and owner, told us when we called to discuss the wines that were sent us a month before the Michelin announcement. Parsons, 47, who is from England, and says “whilst” instead of “while,” was clearly being charmingly colloquial and humble. He had just recently driven to the vineyards he sources from and works, Hawks’ Nest Vineyard at 6,800 feet and Box Bar Vineyard on the slopes of a mountain that overlooks Mesa Verde National Park, and through Telluride with its movie-set vibe and mountain peaks. “I was thinking. It’s a beautiful state. This is so beautiful. There are worse places to live,” he said, laughing. “I’m really happy with what we have achieved.”

(Ben Parsons)

In one of our very first articles about wine, in Tastings, our column in the Wall Street Journal way back in the late ’90s, we implored readers to visit their local wineries. We noted that people enthused about wines from vacations abroad or wines they had had from the well-trod wine-producing regions stateside. But wineries elsewhere, in some unexpected place, in their back yards? Not so much.

Try them -- not first and foremost because they are in your home state, although eating and drinking local has its merits. But try them because they are often very good wines. No need to grade on the curve or add qualifiers. Making good wine takes dedication. Making it in an off-the-beaten-path location takes that and a lot more. Doing it with vitis vinifera is a considerable feat. Attention must be paid.

In 1987, a hugely talented colleague and wine-drinking friend at the Miami Herald, Colorado-born David Von Drehle, gave us a 1981 Cabernet Sauvignon and a 1982 Zinfandel from Colorado Mountain Vineyards in Palisade, Colo., that bore on the labels, “For Sale in Colorado Only.” Colorado Mountain Vineyards is now Colorado Cellars Winery and, according to its website, Colorado Mountain Vineyards was the first winery in the state to make wine from Colorado grapes, fruit and honey. We found both wines delightful but rarely saw wines again from Colorado, which according to the state has more than 150 wineries.

So we were thrilled when the public relations company Parsons hired asked if we’d like to try some of the wines from The Ordinary Fellow, a 2,500-case winery also in Palisade. We received six, all Colorado-grown and all from 2022 except the 2021 Cabernet, $38.99: Riesling, $23.99; méthode champenoise no-dosage Blanc de Noir, $48 (disgorged in July 2023); Chardonnay, $34, on its lees for 7 months; Pinot Noir, $36.99; and Rosé of Pinot Noir, $26.99. His tasting notes on the Rosé say, interestingly, “aromas of marijuana, strawberry and forest floor.” All of the wines were gratifying and well-balanced, with vibrant acidity and true-fruit tastes. They were beautifully made with a lean and clear throughline that connected them to a singular vision, that of Parsons. In addition to the two Colorado vineyards, he sources grapes from four he has worked with in Washington. Roughly 98 percent of the wines he makes are from Colorado-grown fruit, he told us.

So we were thrilled when the public relations company Parsons hired asked if we’d like to try some of the wines from The Ordinary Fellow, a 2,500-case winery also in Palisade. We received six, all Colorado-grown and all from 2022 except the 2021 Cabernet, $38.99: Riesling, $23.99; méthode champenoise no-dosage Blanc de Noir, $48 (disgorged in July 2023); Chardonnay, $34, on its lees for 7 months; Pinot Noir, $36.99; and Rosé of Pinot Noir, $26.99. His tasting notes on the Rosé say, interestingly, “aromas of marijuana, strawberry and forest floor.” All of the wines were gratifying and well-balanced, with vibrant acidity and true-fruit tastes. They were beautifully made with a lean and clear throughline that connected them to a singular vision, that of Parsons. In addition to the two Colorado vineyards, he sources grapes from four he has worked with in Washington. Roughly 98 percent of the wines he makes are from Colorado-grown fruit, he told us.

“Most of the work happens in the vineyard and then when it gets in the winery, you have to not mess it up and let it do its own thing. There is balance in my wines and great acidity in my wines and it’s 26 years of winemaking -- knowing what to do and what not to do, not having a heavy hand,” he said.

“I’ve been through that whole new-oak over-extracted high alcohol thing back in the early 2000s and I don’t enjoy those wines anymore. I want to make wines that I want to drink and I want to make wines that go with food. I love acid. Honestly. I rarely drink red wines. I love Riesling and I love Chenin Blanc. Those are my kind of wines, and if I drink reds, I’m going to drink Pinot Noirs.”

He has called Colorado home since 2001 after winemaking stints in Australia, where he got a degree in viticulture and oenology from the University of Adelaide, and New Zealand.

He was early to the urban winery trend, setting up in downtown Denver, and the wine in kegs and cans trends—hat tip to craft breweries--with pioneering winery The Infinite Monkey Theorem, which in 2016 was Colorado’s top-selling winery, he told us. In 2019 he sold The Infinite Monkey Theorem business, which also has outposts in Texas and is distributed in 42 states. He is currently a minority shareholder of that venture but not involved in any part of its operation “whatsoever,” he said.

“I didn’t think I could take it any further. Honestly, it was time to move on, to get back in the vineyard and grow grapes and make the best wine I could. I felt that the canned wine market was becoming kind of saturated and the opportunity to exit was becoming less probable.”

Born in Kent, Parsons studied animal science in college and thought he’d become a veterinarian. His father was in insurance and although his dad drank wine, his father’s more-favored tipple was single malt scotch whiskeys. To earn some money, Parsons worked at a couple wine stores and upon visiting a winery in New Zealand thought he might enjoy making wine instead of just selling it to others.

But how did he get to Colorado? “I was back in in UK briefly like in summer of 2001 and was looking for a Northern Hemisphere wine harvest placement and stumbled upon a job listing in a wine country classifieds publication for a job as a winemaker in Palisade, Colorado, for an estate winery. I didn’t even know there were wines in Colorado. I applied for it like you used to do with a résumé and a cover letter and three days later, they hired me sight unseen and without an interview. I moved from London to Grand Junction on the 9th of September 2001” and went to work for Canyon Wind Winery.

But how did he get to Colorado? “I was back in in UK briefly like in summer of 2001 and was looking for a Northern Hemisphere wine harvest placement and stumbled upon a job listing in a wine country classifieds publication for a job as a winemaker in Palisade, Colorado, for an estate winery. I didn’t even know there were wines in Colorado. I applied for it like you used to do with a résumé and a cover letter and three days later, they hired me sight unseen and without an interview. I moved from London to Grand Junction on the 9th of September 2001” and went to work for Canyon Wind Winery.

While there, he started consulting for 15 wineries including Sutcliffe winery in Cortez, Oregon, where he got along well with the British owner and in 2005 went to work there. After his father died in 2007 and he inherited some money, Parsons decided to strike out on his own with The Infinite Monkey Theoreum in bottles and then kegs and then cans, all with the intention of making wine more accessible. He had seen enough of how elitist wine could be, working in England. The Ordinary Fellow is named after a pub there and there are rules that The Ordinary Fellow lives by: “He keeps his pinky down, drinks drip coffee, doesn’t care how you say tomato, will drink wine out of any glass and prefers tap water.” The brand’s labels, which look like a psychedelic dream from Peter Max, are anything but ordinary and tell Parsons’ story of travel and adventure along with tasting notes. There’s even a nod to his family, a framed picture of a husband and wife and two children.

Back in 1968, long before his 1973 Stag’s Leap Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon S.L.V. won the red wine competition at the Judgment of Paris in 1976, Warren Winiarski was lured away from the new Robert Mondavi Winery in Napa to Colorado. Gerald Ivancie, a periodontist there, hired Winiarski to figure out how to get grapes from California to Colorado to make wine, which jump-started Colorado’s wine industry. Although Winiarski left that venture after two years to refocus on Napa, he remained convinced of the promise that Colorado held for winemaking. In 2021, the Winiarski Family Foundation awarded a $150,000 grant for an endowed scholarship and established the Warren Winiarski, Gerald Ivancie Institute of Viticulture and Enology at Colorado Mesa University. The college says it is the first in the state to offer a degree in viticulture and oenology.

We asked Parsons what the biggest challenges facing winemakers in Colorado are today?

“The biggest challenge here in terms of viticulturally, when you look at the state in general, is the short growing season-- 155 to 160 frost-free days compared to Napa, which has 250 or something. Some people are adapting by planting non-vinifera hybrids and stuff. But my argument is Colorado wine is already a hard sell and throw a hybrid in the mix that no one has ever heard of, and now you’ve got an unknown wine region and an unknown varietal.”

Then there are the residents of Colorado, 85 percent of whom live in what is referred to as the Front Range.

“One of the biggest challenges is awareness, not just nationally. Colorado wine is doing all right nationally, but even like locally, most of the people who live on the Front Range have never even heard of Colorado wines and our wines are in the best restaurants. I still think that brands are built on-premise. Having the backing of a sommelier and a wait staff that can literally choose any wines to have on their wine list and they’ve chosen a Colorado wine, that gives us credibility.

“Those guys don’t have to qualify by saying it’s good for Colorado,” Parsons told us. “It’s a good wine in general. That’s a feather in our caps and I want to plant a flag and be like, ‘We make good wine and it just happens to be in Colorado.’”

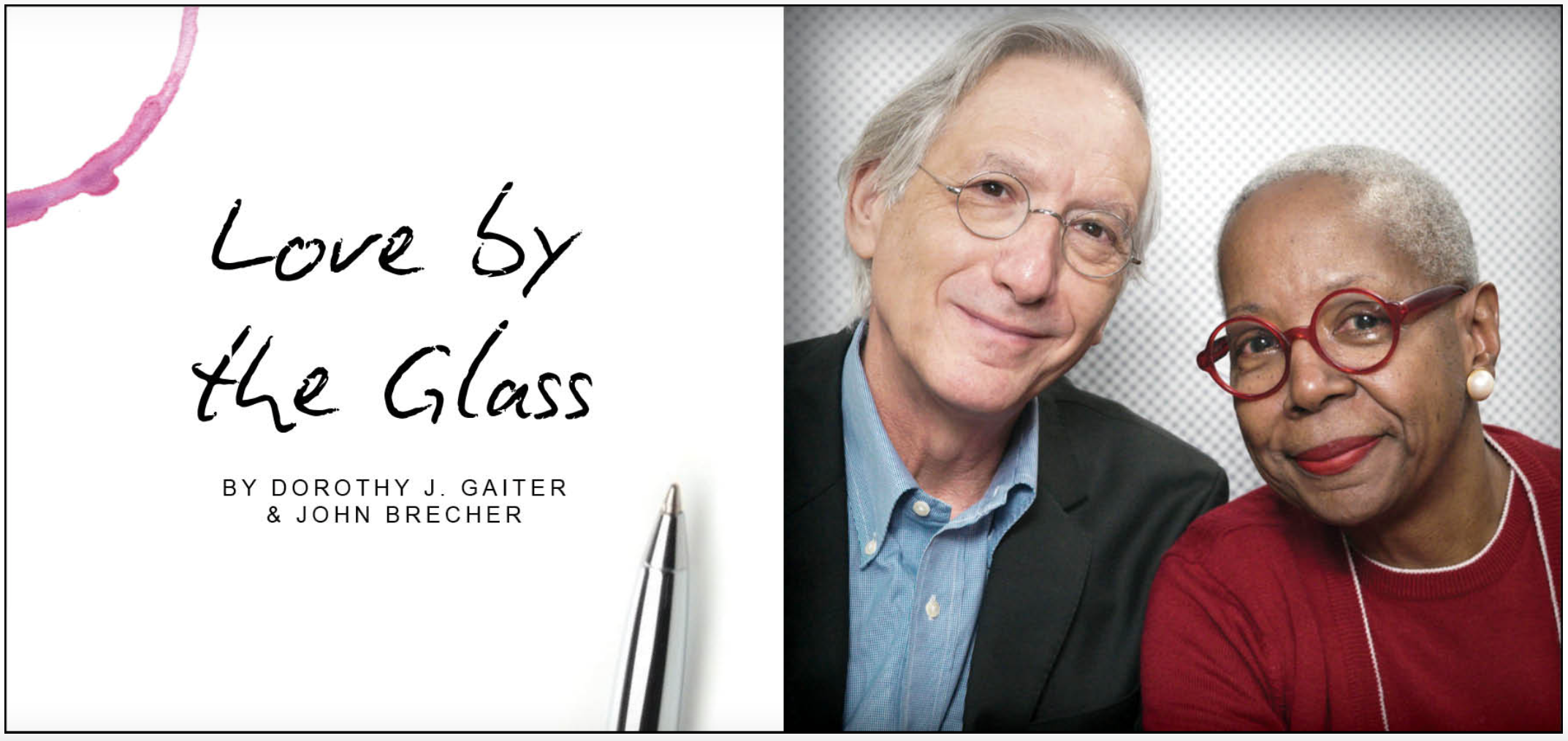

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett