We just watched Drops of God, the Apple TV+ series about wine. No spoilers here, although Dottie, a frustrated screen writer, ruined it for John by guessing way too early a pivotal plot line. Nevertheless, we would recommend it for wine lovers and those who have wondered what the fuss surrounding wine is all about. It was most interesting to us when it touched on the importance of terroir in thoughtfully made wines. Not just geography, as many people think of terroir, but the people who make it, how they make it, and the consequences of climatic factors that Nature deals them in every vintage.

Last week, a few days after we saw the series finale, we read an Associated Press report that two U.S. Democratic senators, Patty Murray of Washington and Alex Padilla of California, had introduced legislation “to better protect winegrape growers in Washington, Oregon, and California—the top three states for wine production in the U.S.—against wildfire smoke damage.” The AP also reported Representatives Dan Newhouse, Republican from Washington, and Mike Thompson, Democrat from California, co-chairs of the Congressional Wine Caucus, had introduced companion legislation in the House. Aside from funding more research into smoke taint, the legislation would also order federal officials to develop a policy “to insure wine grapes against losses due to wildfire smoke exposure.” Thompson and now-retired Republican Congressman George Radanovich founded the caucus in 1999 and used to assist us in our Presidential Wine Taste-Offs when we wrote “Tastings,” the Wall Street Journal’s wine column. In January, the feds announced $930 million in funding to 10 states for programs to reduce wildfire risks. With smoke from Canada’s wildfires still wafting in the U.S. and now in Europe, winemakers surely are watching the newly introduced legislation. Meanwhile, a scorching heat wave is moving across the country and authorities have attributed at least 15 deaths to the rising temperatures.

Within days of that AP report, Wine Growers British Columbia (WGBC), a trade organization, announced the results from a report it commissioned on the devastating short and long-term effects of what it termed the “climate change related freeze events” last December. Megadrought-stricken Chile is reeling from its wave of at least 405 separate fires earlier this year that killed 24 people and destroyed more than one million acres including homes and vineyards. This new round follows fires in 2017, which had been called the worst in the country’s history, killing at least 11 people, destroying billions in structures and acreage, including vineyards. So we reached out to Paul McRostie, winemaker of Santa Rosa de Lavaderos in the Maule Valley whose old-vine País we wrote about last year. Vineyards in New York’s Finger Lakes and parts of the Hudson Valley were damaged by frost in mid-May. And in late July we will open the International Pinot Noir Celebration 2023, which will feature, among many interesting classes, discussions on the impact of climate change globally on Pinot Noir and the benefits of truly sustainable farming.

As if making wine was not hard enough!

(Photo: Fred Frank, left, Dr. Konstantin Frank’s Vinifera Wine Cellars; Richard Ball, New York Commissioner of Agriculture; and Hans Walter-Peterson, viticulture extension specialist, examine damage along Keuka Lake. Photo credit: Mark James, New York Farm Bureau)

Hans Walter-Peterson, senior viticulture extension specialist for the Cornell Cooperative Extension, has done cooperative extension work for more than 20 years and has worked in the Finger Lakes region for 16 years. A day after the overnight below freezing temperatures hit, he told Tracy Schuhmacher of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, “I’ve never seen spring frost this bad. This is the worst I’ve ever seen. We’ve never had just a region wide event like this.” He later toured the area with New York Agriculture Commissioner Richard A. Ball, who could recommend that the area receive disaster relief. We called Walter-Peterson this week and asked if his early assessment of damage had held. “Yes,” he said. “It’s a lot of growers saying the same thing and they’ve been here a lot longer than I have. They’re still going through bloom, waiting to see how many grapes end up in clusters. But my educated guess is that we’re probably in the neighborhood of 35 to 40 per cent yield loss across all varieties, all vineyards.

“Based on what I’ve seen, some vineyards, some areas, have almost no damage at all. In fact they’ll have a pretty healthy crop. And there were other areas, where almost all vines got hit. It’s all about location, as these frost events always are,” he added.

We asked if he had heard anything from Ball about disaster relief. “Things are still in the works. I was just on the phone with him 20 minutes ago. We’ve been in contact with other commissioners in the Northeast, too. Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Maine that also got impacted with other specialty crops like fruits. It’s not just grapes that were affected. There’s definitely enough damage in the Finger Lakes to quality for disaster relief,” Walter-Peterson concluded.

In British Columbia “Initial forecasts following the freeze event showed a potential crop reduction of 39 to 56 per cent. Following budbreak, our industry-wide research concluded that our worst fears were realized with a 54 per cent reduction in 2023 and 45 per cent of total planted acreage suffering long-term irreparable damage,” Miles Prodan, President and CEO of Wine Growers British Columbia, is quoted in the report. In terms of direct economic impact, the organization estimates the wine industry will lose $133 million and that suppliers, wine stores and restaurants may lose more than $200 million, with fulltime vineyard and winery jobs down by 20 per cent.

The projected losses are most severe, at least 60 percent of the crop, in the south Okanagan Valley, Kelowna and Similkameen Valley, the report states, with Syrah, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon suffering projected losses of more than 65 per cent.

We reached out to Anthony Gismondi, https://gismondionwine.com/ longtime BC wine writer and host of a weekly radio show we appeared on in February to discuss Open That Bottle Night, to ask what he was seeing and hearing on the ground about the freeze event. He wrote back that the “catastrophe” was a couple years in the making.

“The vines were assaulted by a blistering heat dome in the summer of 2021, creating a tiny crop. A frigid 2021 winter inflicted more winter damage before a wet spring in 2022, delaying the flowering and set, pushing back what turned out to be a huge harvest that benefited from an old-fashioned, long, warm Indian summer that, while ripening all varieties to perfection, saw the vines working long into November leaving little time for the vines to properly shut down before the temperatures dropped precipitously on December 27.”

“It must be said editorially that what we know now is that in a young region eager to expand, it is clear some grapes were never planted in the right areas, and some of the parts probably never should have been planted with any grapes,” Gismondi wrote. “From a terroir point of view, it is a fabulous teaching tool in that particular grapes in certain blocks did not survive while others performed well.” The damage will be a challenge to overcome over the next three years, he wrote, “but spirits remain high, and replanting is on everyone’s mind.”

As we wrote about País last year, it was the first vitis vinifera planted in the New World, Mexico in the 16th century, and was planted in California in the 18th century, becoming the mother grape of the California wine industry. It’s known as Mission in the U.S. and was planted widely for a time to make sacramental wine. It and Carménère are Chile’s signature grapes. We reached out to McRostie and he told us that his family’s hillside vineyards, with some vines older than a century, have been spared smoke damage and so far unusually heavy rains, also a consequence of the warming atmosphere. “I’m certain the vineyards haven’t suffered from erosion. They received some water coming from the near-by small hills, but it wasn't something the cover crops and weeds they have this time of the year, could not support,” he wrote us. As Walter-Peterson noted about threats to other crops, McRostie told us, “Some fields which had corn were recently plowed. The river (with current) got into them and probably caused a lot of erosion. Only when the water retreats we will be able to see the extent of damage, but probably it will be bad. Maybe we have to think about plowing less (make a more regenerative agriculture).

As we wrote about País last year, it was the first vitis vinifera planted in the New World, Mexico in the 16th century, and was planted in California in the 18th century, becoming the mother grape of the California wine industry. It’s known as Mission in the U.S. and was planted widely for a time to make sacramental wine. It and Carménère are Chile’s signature grapes. We reached out to McRostie and he told us that his family’s hillside vineyards, with some vines older than a century, have been spared smoke damage and so far unusually heavy rains, also a consequence of the warming atmosphere. “I’m certain the vineyards haven’t suffered from erosion. They received some water coming from the near-by small hills, but it wasn't something the cover crops and weeds they have this time of the year, could not support,” he wrote us. As Walter-Peterson noted about threats to other crops, McRostie told us, “Some fields which had corn were recently plowed. The river (with current) got into them and probably caused a lot of erosion. Only when the water retreats we will be able to see the extent of damage, but probably it will be bad. Maybe we have to think about plowing less (make a more regenerative agriculture).

(Photo: Dottie with Paul McRostie)

Others have not been as fortunate.

The large and influential Spanish-owned wine enterprise Miguel Torres has been instrumental in reinvigorating the cultivation of País, especially old-vine País. Its partnership with 19 small winegrowers, known as the Viñedos Esperanza de la Costa Association from Chile, works to bring back this and other ancestral grapes. Miguel Torres Winery makes Estelado Brut Rosé, $19, which it says is the first traditional-method País bubbly. A Torres representative sent us a bottle recently and Dottie liked it more than John. After decanting it to smooth some of its rusticity, she found it savory, with black pepper, orange zest and earth, reminiscent of some orange wines we have tried.

Eduardo Jordán Villalobos, chief winemaker and technical director of Miguel Torres in Chile, wrote us in a statement about the February fires: “Over here the consequences of the fires have been terrible, many hectares of forests burned and this time unlike the 2017 fire, there are 24 victims and I have seen a greater number of vineyards, many of them centenarians, in addition, houses, and even wine cellars of small artisan producers.” One grower lost 30 per cent of her old Cinsault vines, he added.

Eduardo Jordán Villalobos, chief winemaker and technical director of Miguel Torres in Chile, wrote us in a statement about the February fires: “Over here the consequences of the fires have been terrible, many hectares of forests burned and this time unlike the 2017 fire, there are 24 victims and I have seen a greater number of vineyards, many of them centenarians, in addition, houses, and even wine cellars of small artisan producers.” One grower lost 30 per cent of her old Cinsault vines, he added.

(Photo: Fire Damage in the Itata Valley)

Villalobos wrote, “The areas that have been most affected in terms of vineyards are the Itata and Bio Bio valleys where a large part of the ancestral vineyards are located, some of which are more than 200 years old and have been an important part of Chile's viticultural history” such as Muscat of Alexandria and País, “introduced by the Spanish more than 400 years ago.”

He continued, “Undoubtedly, a year of great challenge for our technical team, in terms of vinification of grapes that were exposed for a prolonged period to smoke but we already have more experience after

what happened in Chile in 2017.”

This week, Miguel A. Torres, the fourth generation in his family’s business and president of Familia Torres, was quoted in Decanter imploring winemakers worldwide to join International Wineries for Climate Action (IWCA), founded by him and Jackson Family Wines, to work together to reduce carbon emissions. It currently has 41 member wineries from 10 countries.

In Oregon at the International Pinot Noir Celebration, July 28-30, Greg Jones, an atmospheric scientist and wine climatologist, will share his studies on what climate change will do to Pinot Noir globally by 2050.

Our friend, Brian Freedman, a journalist and author of “Crushed: How a Changing Climate Is Altering the Way We Drink,” will lead an international panel of winegrowers and winemakers in a discussion about successful ways to reduce the footprint wine has on the environment.

At the end of his statement to us, Villalobos in Chile echoed something William Harlan of Harlan Estate told us earlier this year at the Wine Writers Symposium at his Meadowood Napa resort, which lost some structures and woodlands in the wildfires of 2020. He explained that among other things, a sizable portion of forest is being replanted with native species of more fire-resistant trees.

Villalobos wrote, “Another important thing after what we experienced this season and the mega fires we had in 2017, is that I hope we learn as a lesson, the importance of the design of forest plantations that

allow greater security, the use of firebreaks and the earlier reaction of the government entities responsible for attacking the fires.”

Amen to all of that.

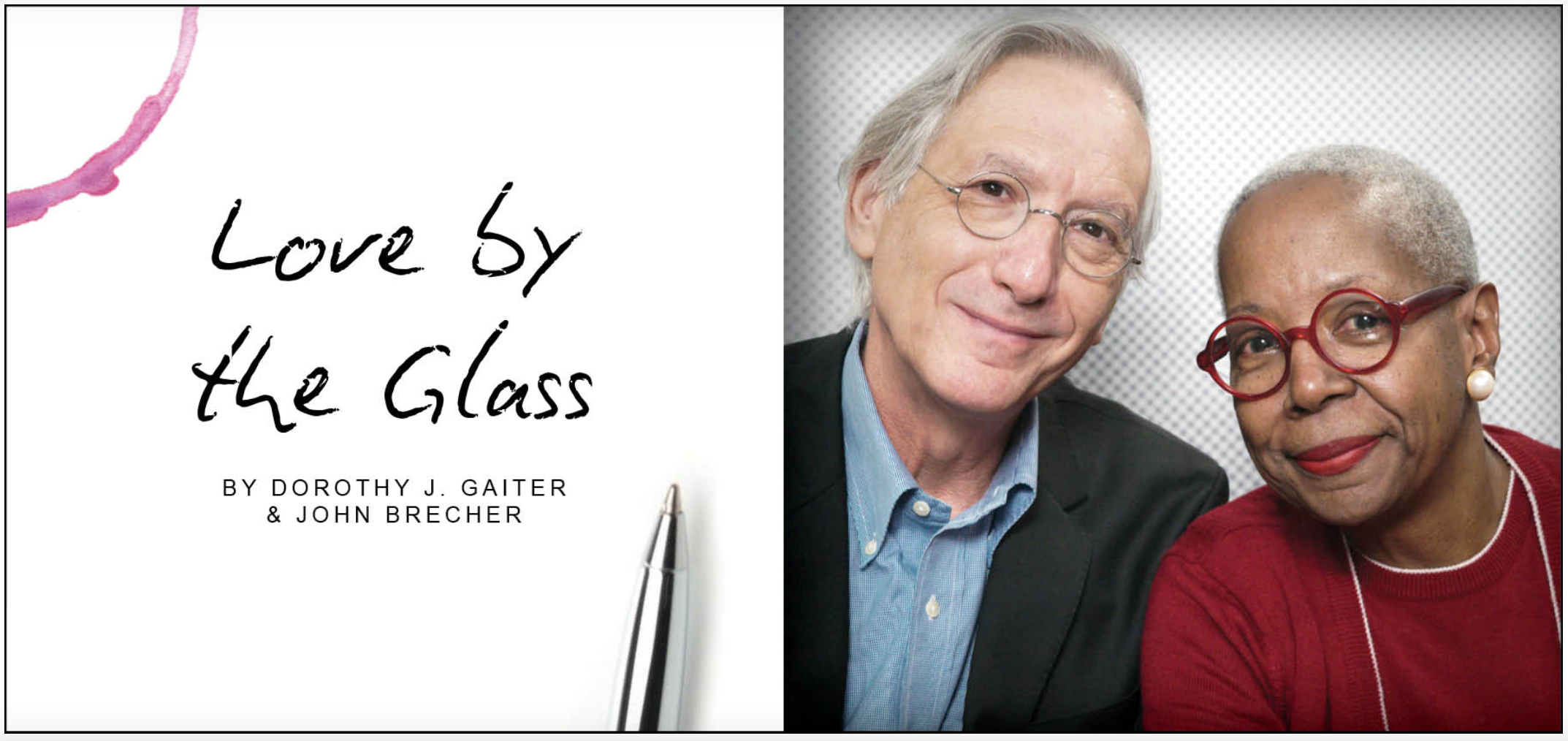

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett