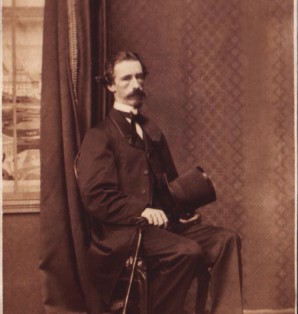

Errázuriz is a family-owned winery located in the far north of Chile 65 miles outside of Santiago. Don Maximiano Errázuriz founded Viña Errázuriz in 1870 and planted the first French grape varieties in the Aconcagua Valley. Today Errázuriz is managed by Eduardo Chadwick - the fifth generation of his family to be involved in the wine business. Chadwick has overseen many significant advances for Errázuriz including developing never before planted coastal areas, launching an icon wine Seña in 1997 to compete with the Bordeaux First Growths, and partnering with Robert Mondavi.

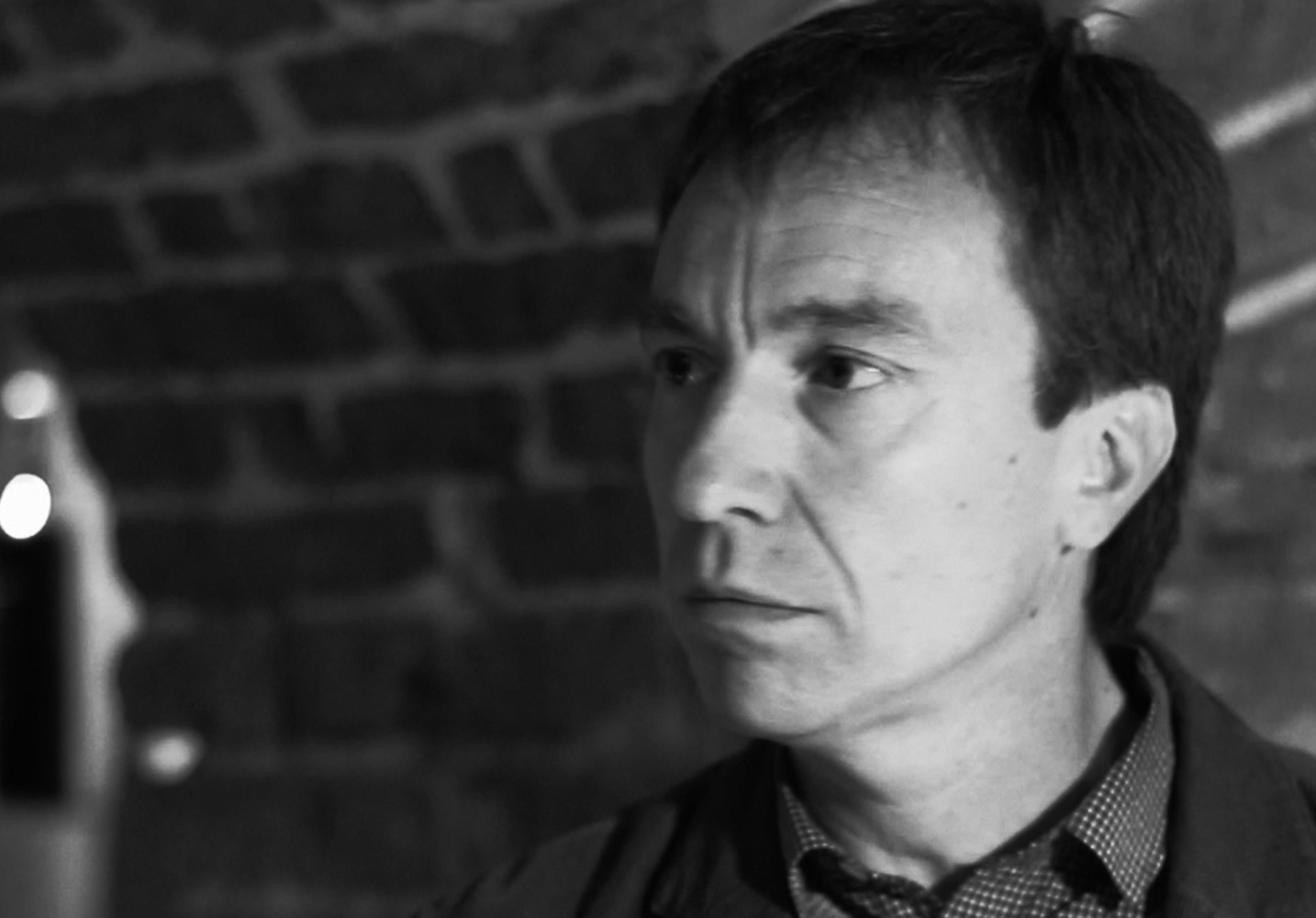

Winemaker Francisco Baettig started at Errázuriz in mid-2003. He has more than 1,000 acres of vines to work with in the cool climate Aconcagua Valley.

(Pictured founder Don Maximiano Errázuriz)

Christopher Barnes: Francisco, tell us about Errázuriz.

Francisco Baettig: We consider Errázuriz an old and classic winery. It was founded in 1870, so really it's been around a long time, but at the same time, it's a very unusual winery. Why? Because it's a family-owned winery. The owner is a very energetic and involved person, a young person, with a passion for wine. He's always trying to maintain the heritage and the history of the winery, but at the same time, looking for new things, improving, and moving forward in every aspect. It's very attractive to work here because it's a link between the past and the future.

How did you end up at Errázuriz?

That’s a good question. Faith, I guess. I started as a winemaker in Chile. All winemakers are agronomists, or agriculture engineers as I think you say. We start with agronomy and at some point, you choose your specialization, the specialty you want to go into. I decided to go into winemaking because Chile has produced wine for many, many years, since the Spanish arrived in the 16th century. But the modern way, to export high quality with more technology, started in the beginning of the ‘90s, end of the ‘80s.

I've had to make my choice as an agriculture engineer. Chile was just starting to export, to improve quality, to have articles in the press about the new things going on. I felt it was very attractive, very interesting to be part of that rebirth and the new challenges for Chile in the wine industry, so I decided to go there. I started in other wineries, Casa Lapostolle, maybe you heard of it from Colchagua, where Michel Rolland was a consultant, so it was very interesting for me to be there. Then I studied in France, I did a master degree in Bordeaux. I met my wife there, and I kidnapped her. When I came back from France, I started in Errázuriz.

What would you say are your main influences as a winemaker?

I was influenced by Michel Rolland at Casa Lapostolle. He was very well-known and had a big influence on the wines he made. But then you start to try to find your own way. You take things that makes sense to you, and then you have your own evolution. Actually, in Chile, when we started this new development, in the beginning of the ‘90s, there were not a lot of winemakers. There were very few winemakers because it wasn't a very developed area in Chile, so a lot of young winemakers ended up managing a winery. At that time, we didn’t really have a lot of experience, so you sort of follow a little bit what the market demands, or the consultant, and at some point, you start to find your own way.

Chile is very far away from all other countries, but Chileans began to travel, and to visit producing areas. Since we are so very far away and it's very hard to find wines from overseas, we're all inspired to travel and visit the different wine producing areas like France, for example. That was how I started to be influenced, and my style also, from visiting France. I studied in France, and at some point, you find the style of wine that represents you, and that's when the evolution occurred for me.

Francisco, tell us a little bit about the terroir of Aconcagua.

Aconcagua is a valley north of Santiago, not too far, about 80 kilometers north of Santiago. It's a narrow valley. It's not as wide as Maipú, which is in the middle, around Santiago. This narrow valley goes from the coast, the Pacific ocean, to the Andes, and it's shaped by the Aconcagua River. It's a very particular valley in that sense, because it goes from the Andes to the Aconcagua Coast, so it’s a more restricted area, more central or coastal. It's a valley that has some influence on the temperature here. It's drier and slightly warmer than the classical Maipú, because we're further north, so it’s very good for producing late ripening varieties in the interior part.

In Chile, the closer you get to the Pacific ocean, the cooler it becomes because we have the Humboldt current, the Humboldt stream coming from Antarctica. And the closer you get to the Pacific it’s cooler, and the more inland you move, you lose that influence of the cooling breezes from the Pacific, so you have warmth. In this valley, we have mainly rain in winter, so if you're inland, we have late ripening varieties. It's a very healthy valley in terms of disease, we don't have a lot of rain. As you move to the coast, you arrive at a cool climate valley, so it's a very diverse valley, because we can go from extremely cool on the coast to extremely warm.

Here, it's moderately warm, so we can produce Cabernet. If you continue to move farther inland, it becomes really warm, and we can produce Mediterranean varieties, like Grenache or Mourvèdre. It’s a very interesting valley in the sense that in one valley, you can go from Pinot Noir, or cool climate varieties, to Mediterranean varieties in the same area. Then you have the diversity of soil that gives particularity to the wines. So, you have diversity of soil as well as climate. Really, it’s a very particular valley because of its diversity.

Is there a grape that you feel is the star of this area, or do you feel there are multiple stars?

It's been a big debate in Chile if Carménère, for instance, should be the flagship for Chile, or if Cabernet is still the flagship variety. I think Chile has a big, big advantage which is its diversity. In my personal opinion, I don't think Chile should stick to just one variety or use Carménère, the equivalent of Malbec in Argentina, or Sauvignon Blanc in New Zealand.

Chile is 40,000 kilometers long. If you had visited 10 years ago, or maybe 15 years ago, the producing area was going from the classic Aconcagua area, Aconcagua here down to Maule. That's more or less 600 kilometers. Today, if you want to visit all places, you have to go 1,200 kilometers from Elqui to Traiguen, Malleco south. That's north to south, and then the diversity we've been developing in the last 15 years is from the coast to the Andes. In the Andes, we were very limited in development, now you will find more and more vineyards there, and also on the coast. I think today, the challenge is to improve, fine tune the style and the quality of the wines. We can produce a very attractive Chardonnay or Pinot on the coast, to very attractive Carignan in the dry farming area in the south, to a very attractive, I don't know, Grenache more inland and the classic Carménère. I mean, Chile is very particular in that sense with a diversity that I think we should explore more than one variety.

Francisco, Errázuriz is a very old company, and yet you're known for innovation. How did that come about?

We’ve had a lot of firsts. First to plant in the foothills with drip irrigation, first to bring all the varieties, first to create an icon or flagship wine. We carry many firsts. It's part of the DNA and goals of the owner, so it's very challenging, but at the same time, it’s very attractive to work here. We have here, for instance, a Pinot Noir from the coast, from this Aconcagua Costa region. It is also a new area that was just planted in 2005, so it’s a very new place, near the ocean, and a very exciting area for us.

Talk about some of the innovations that you've undertaken here.

We have many. We have an interesting project on the coast. I'm trying to, how to say, to access and to develop an appellation within these properties to handle 30 hectares, planted, with Pinot, with Chardonnay, cool climate Syrah, and Sauvignon Blanc with this particular shist soil. I think we have a very particular terroir that I'm trying to map in terms of style, and quality potential and then relate it to the wine, so we can create products that are closely related to the terroir, rather than just creating labels.

That's a very appealing project. We have done that with a Pinot, we worked with the French producer, she’s well-known. Then I brought a geologist from Burgundy to help us to do all the mapping and divide the qualities or the style, like the Grand Cru. We won’t use those names of course, but that's the concept, and it's an interesting undertaking that we’re developing today but we have many, many others.

Francisco, tell us about the partnership with Mondavi.

Robert Mondavi came to visit Chile I think at the beginning of the ‘90s. Eduardo Chadwick, the president of Errázuriz, was very young at that time, and he was his chauffeur, so he moved him around, he contacted the wineries, and he showed him the different wine areas of Chile. They became friends, and then they start to talk about an idea, a project, and to create a joint venture, like he did with Opus One and to start developing Seña. Then in '95, they came here many times and founded the place which is now Seña, and developed, planted, and started to produce his wine.

Then Mondavi is sold to Constellation.

Yes. In 2004, it was purchased by Constellation, and Eduardo wanted to work with it, with the people, with the family, not with the corporation, so he purchased Mondavi’s share. Since 2004, Seña wine is Errázuriz and Eduardo Chadwick owns the project.

Tell us about getting into the icon category. When you came out with your first icon wine, there were a few eyebrows raised. How did that happen and what has happened since?

I think it's understandable that people were surprised. Chilean wine was mainly known for entry level wines at, let's say roughly $10 a bottle, then suddenly the price jumped to $100 a bottle or $50 a bottle at that time for Seña. People were very surprised and I can completely understand it. Also, Chile started to export. Chile has always produced wine, and wine is widely consumed in Chile, but as a product in the market around the world, it was fairly new. People knew Chile by these entry level wines but not by this very expensive wine. I think it's something that we needed to create, maybe we went a bit too fast, we could have done it more slowly, filling the gaps step-by-step. The goal was to show that Chile had the potential for producing world-class wine. The terroir, the climate, all the conditions were there to produce fine wines. That was the point of these wines.

In terms of the Chilean wine industry right now, what are the biggest challenges that it faces?

There are many challenges. If you realize that we only started to export wine, not produce, it's only been 30 years and the wine production is nothing, it’s really nothing. I don't want to sound pessimistic, because really what we've done in the last 30 years is huge. From not being in the market, now we're everywhere, the Chilean brand is known, but I think we have a big challenge in terms of moving up and moving away from this idea of good price, cheap good quality wine, which is difficult when you are set in one category, it’s very difficult to move forward.

We've been consistently moving up and changing things, like paying more attention from the beginning, the plant material, the origin, the soil, the market, developing new projects, small projects. I think the fact that new players are coming into the scene is great, and we needed that, because that pushes the big guys and that also give more sense of place to different projects, it gives more complexity, diversity to the country. I'm really optimistic in terms of what's going on. I feel that the winemakers, we are all there, and we're fine tuning, and finding the style that represents us more. I think there are still many changes in terms of reaching the consumer, showing the new Chile, which is a reality today.

Today, that's the main challenge. I think we really have the potential, the terroir the quality, all that, but we have to do more work in terms of communicating, reaching the market, reaching the consumer, but the quality and the style is going in the right direction, and Chile has become really more diverse in not just product, but also in producers. Chile used to be the least automized producer in the world.

Internationally Chile is known for this sort of value, but inexpensive wine. There are a lot of very innovative things going on, which you're doing, but how do you get out of the mindset that associates you with these inexpensive wines and focus more clearly on the interesting things that are happening in the country?

It depends a lot on the market too, because if you go to Asia, for instance, where there's less preconception, and the consumer has less experience, so to speak, they are more open to trying different things. We do, for instance, with our icon or flagship, we do very, very well. We sell very well and since they try just the quality wine, we do very well. That's one thing market-wise. Then also all these new things, new wines that we're producing, what we need is for the consumer to just try the wines. When we show what we have done in the last five years, in Chardonnay, Pinot, Sauvignon Blanc, you name it, people are really surprised. They really think the wines are worth it and it is still a bargain. But we need to reach the consumer. That's a long-term challenge, but I'm very confident. In the last five years, the evolution has been very fast and very positive.

Francisco, where do you see the future of wine in Chile?

I don't know. I see huge diversity, and I see the consumer starting to really appreciate that. This is something that we need to create, but it's real. I really like the diversity because it provides more opportunity, you're not sticking to just one variety, you’re reaching a more diverse consumer. I think Chile requires some structural changes in my opinion, for instance, working a bit more in the appellation system. That, for me is a little bit broad, or too loose. We need to promote specific places, or local areas.

We require some changes there, and we have to balance, as a wine producing country, reaching the consumer, but at the same time, to show more and more personality in the wines. Wines with a sense of place that are supported by a more formal appellation system, maybe not as complicated as France, but I think we have to work a little bit on that. I think the potential in terms of quality and style is huge, and we're just starting to feel more confident. When I make wine, I feel that I don't have to explain the wine. People try the wine and they appreciate the wine.

In the past, we were saying, "This is like this, this is like that. We want to be like this or that." Today, the personality of Chile is starting really to show, so I think it's a bright future, but with a lot of work, of course.

You're not of the opinion that Chile should stick the flag in the ground for Carménère?

Not really. I think Carménère is interesting to have as a signature variety, or variety that you can identify, a little bit like ours, but I think it would really be a mistake to stick to just one variety. The quality potential is huge in many varieties and that's Chile. Chile's diversity is long, 40,000 kilometer long, from the coast, Andes, north, desert, lakes, et cetera, so we really need to touch on that, and to do that.