There is something very satisfying about the Hermann Wiemer story. It has that "hard work gets you somewhere and nice guys finish first" feel to it.

In 2001 Fred Merwarth started out as an apprentice at the winery, getting his job with a cold call to Finger Lakes wine legend Hermann Wiemer. Wiemer, a German who had worked in Mosel and emigrated to the US, had been one of the pioneers in the industry in the 1970s pushing the region to create quality wines.

After many years of hard work, from cleaning barrels to learning the trade of winemaker, Merwarth took over the operation in 2007. Merwarth and Wiemer worked out a deal that transferred ownership and day-to-day management of the winery to him and Oskar Bynke, the general manager and a college friend.

The team at Wiemer is constantly pushing for innovation. They have engaged in co-producing a wine with three-star Michelin restaurant Eleven Madison Park, and own one of the largest vine nurseries on the east coast. The wines are served on the wine lists at some of the countries top restaurants.

Christopher Barnes: Fred, tell us about Hermann Wiemer and this estate.

Fred Merwarth: Hermann Wiemer, as an estate, is situated on the west side of Seneca Lake. We are one of the older Finger Lakes' wineries. Hermann actually bought the property in 1973 and planted his first vineyards in 1974, making it not only one of the first vinifera plantings in the Finger Lakes, but also the very first vinifera planting on Seneca Lake. We think back just 40 years, and that's a very short time frame to be experimenting and trying to figure out how you grow these more delicate varieties.

Hermann, as the person, came here in 1967 and actually started with Bully Hill. As he was working with Walter Taylor, he realized that was not the business he wanted to be in, bought the farm, and started here. We always think of Hermann as one of those real pioneers. Somebody who really just took on the idea and tried to figure it out, almost by himself, without a lot of infrastructural help in terms of where do you get presses and pumps. He really figured it out. As a person, he was very committed to making great wine here on Seneca Lake. That's our real story, our commitment to continue making great wine here.

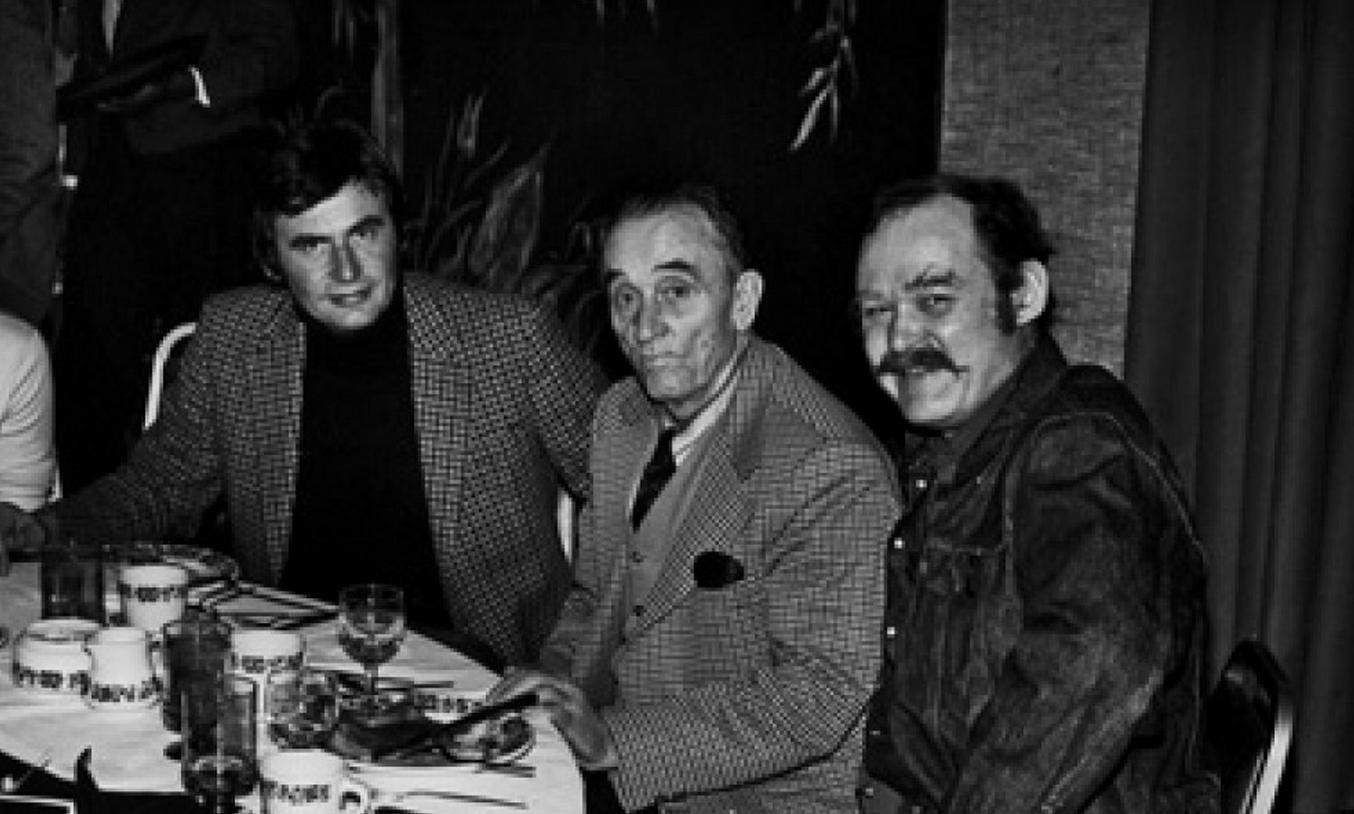

Photo: Oskar Bynke, Hermann Wiemer, Fred Merwarth

Fred, tell us about how you started working here for Hermann, as his apprentice, and then ended up taking over and becoming winemaker.

The story of how I started here with Hermann is kind of interesting. I actually grew up on a big dairy farm. So, I grew up in agriculture and I went to Cornell, in a horticulture major with 'ag' business. Midway through my junior year, I decided to study abroad in Germany. When I was over in Germany, I had a phenomenal experience with a young winemaker who was the fourteenth generation to be making wine in his domain and had just taken over from his father. They had been making wine there since the Romans left. I was just awestruck by how intertwined culture and history is around that industry, that agricultural industry.

When I think back to Cornell, I took some courses that really weren't very interesting. What I did, I cold-called Hermann. I tasted his wines at Cornell and I said, "There's this crazy German guy on the west side of Seneca Lake. I should call him and see if he could help me find an estate in Germany to work with." So, I called Hermann. He threw me a line, "I've been waiting so long. I don't know anybody, but if you want to come here then we will talk about any opportunity here." So, I drove up here in the dead of winter, interviewed with Hermann, and started March of 2001 in a very formal, practical training. There were basically just five full-time employees here at the winery, including myself, when I started. It was a tremendous opportunity to get my hands involved in the winery aspect, the vineyard aspect, and specifically the nursery aspect. Just learning how to prune and tie, clean tanks and clean bottle rinds, and ultimately all the other understanding of making wine, especially from a viticultural standpoint, came about then.

How has the winemaking changed here over the period of time you have been here?

The winemaking has changed slightly, but I think we really have evolved in our winemaking. When I started with Hermann we were really operating off of one main vineyard, like the HJW vineyard here, that was in 2001. In 2002, our Josef and Magdalena vineyards came into the production. One was a property that Hermann purchased and the other was a newly planted vineyard. That fruit came in and completely changed the dynamic of the wines that we were making, because you injected into our traditional wines a greater sense of ripeness. Hermann would be the first one to say that the wines, themselves, had evolved.

In terms of how we work with that fruit, we've gone a little bit further away from conventional practices and, in some cases, very far away from conventional practices. We are not inoculating any of our white wines, no sulfur use until the end of primary fermentation, and absolutely no adjustments to the wine - no sugar, acid, tannin, anything. That has been evolution, basically, since 2004. Have the wines become better? I think that we've worked on understanding our vineyards a lot better, in terms of where you are getting ripeness, where you are getting acidity, where you have bird damage, where you have Botrytis, all of the different variables that you work with during harvest. We have really turned our back away from the winery and said: How do you bring in great fruit? How do you make your wines and pick your wines for that vintage, so that when you turn around and look in the winery you don't have to sit there and scratch your head and wonder how you're going to pull it off. I think that has been one of the big changes.

How has the Finger Lakes evolved as a region since you have been here?

The Finger Lakes has evolved tremendously, even in the last five or six years. One of the big points, looking at the front-end of the industry: the sales, the tourism, we have infrastructure. We are getting more infrastructure now such as bed and breakfasts, hotels, restaurants, and transportation. We are also seeing other activities like agri-tourism and specifically wine-tourism to get people here, so that they can do other things than just taste wine. They can come up for a week with their family and enjoy life in the Finger Lakes. That's a big transition. That's becoming a full 12 month activity now, rather than just mid-May until the first snow flies.

I think within the industry, we have just a tremendous pool of trained people. Whereas, when I started here with Hermann, there were very few trained winemakers. I consider myself untrained when I got here. There wasn't a lot of experiences going on where people were learning to make wine here in the Finger Lakes, and now that is happening. You have another generation of young and middle-aged people who have trained in the Finger Lakes and know the challenges and the qualities that we can reach.

And you are also starting to see Finger Lakes' lines in some of the top restaurants in New York City and outside of New York City. That's a big change, as well.

Yes, watching the wines grow outside the region, you now find them in New York, in D.C., in Chicago. Again, you look back just 10 years and there are very few wineries, thus wines, that have made it into those markets. They are such important markets. New York City is arguably one of the most competitive wine markets in the world. We are only five hours from there. That should be our hub. Then you see these markets having developed in Chicago, Atlanta, D.C., and San Fransisco. These are all markets that are in demand. They are really demanding our wines, and 10 years ago the Finger Lakes was not even on the radar.

Tell us about the viticulture that you do here.

Our viticultural practices are very simple, on one hand. We look at very low input, but I think that they are very complex in the fact that we are working with the soils and trying to figure out how to maintain the soils in a very nonconventional way. That becomes very complicated because the weather and the mesoclimates here in the Finger Lakes are very difficult. So, in the vineyards we haven't used herbicides in over 10 years now and we have very low use of fungicides. We use a classic Bordeaux method of mechanized sulfur and copper sulfate as our primary fungicides, with an organic viticulture, no synthetic or chemical fertilizers, all-natural fertilizers, a lot of compost, and manure.

We have seen a vibrancy within the vineyards. We are using cover crops to maintain soil moisture and decrease weed pressure. It is not easy. It is very labor intensive and it requires a window of opportunity. Here in the Finger Lakes, it is a very small window to get projects done. It forces us to be very strong and very well organized to be able to get cover crops in when they need to be in, or get our spray program done in the time frame that it needs to get done.

Photo: Hermann J. Wiemer, Dr. Konstantin Frank, Walter Taylor

Fred, tell us about the Finger Lakes. What is special about the Finger Lakes as a region?

The Finger Lakes is a cool to cold climate, as anybody living here knows. What makes it special is that we have true mesoclimates. Mesoclimates are the slight differences from one vineyard site to another vineyard site. That creates tremendous differences between the quality of grapes that you are getting from one site, even just two to three miles away. Also, within a block, we have tremendous soil variations from one vineyard site to another. That is very special. Great viticultural areas of the world have these major and minor differences. We are also special because of the lakes. The lakes help moderate temperatures and allow us to grow vinifera varieties. You go two to three miles off the lake and you can't grow these more delicate varieties.

When people talk about the Finger Lakes, they talk about Riesling. Why is Riesling special here? How would you describe Finger Lakes' Riesling?

I think Riesling is special and a very good indication of what we can do here, because if you grow the plants right, they show a true sense of place. It's not to say that other varieties don't, because Pinot Noir and Burgundy have a very distinct taste from one site to another. It is fascinating because it can withstand the winters here. It has a long growing season. You can select quality levels all throughout harvest. You can have a very light, higher acid, very easy-drinking Riesling at the beginning. You can get fruit later in harvest and have opulent dessert wines. That fits our climate. It allows a lot of flexibility, you can get to tremendous quality levels, and it's consistent. That was one of the big marks when Hermann was starting to figure out, in the early '70s, what to plant. Riesling was a natural fit for him, having come from Germany, and trying to figure out how to grow something in this difficult climate.

The true identity of the Finger Lakes, people talk about the acidity, and I think that it's the balance of acidity with its ripeness. The other part is having such differences from one site to another site.

What about other grapes, other than Riesling? What grapes do you see have great potential in this region?

The other varieties that we are doing very well with, and that probably show great potential are Chardonnay, but that has not been planted for a long time, and Cabernet Franc. Cabernet Franc is fairly new to the scene, but wineries are showing that it is growing properly and that you can make very serious and very international styles with it. There is a great debate over Pinot Noir. I think that a sparkling Pinot Noir is absolutely fantastic. I think that we should be doing more sparkling wines here, especially Chardonnay and Pinot-based, and dessert wines. I think many varieties work as a dessert wine, for example Pinot Gris and certainly Riesling, Chardonnay, and Sauvignon Blanc. Wineries are proving that we can make these styles of wines. Other varieties that we have been working with are Grüner Veltliner and Blaufränkisch, two Austrian varieties, that are showing great consistency from vintage to vintage. We grow quite a bit of Gewürztraminer. It's a more delicate variety.

In terms of your evolution as a winemaker, are there other influences besides starting with Hermann that have influenced the way that you've made wine?

That's a great question.

What has influenced me the most, in terms of making wine and evolving within a style, has been the real interest in figuring out what the land can give you and not changing that, or changing as little as possible once you press the grapes. It goes back to our thoughts about you opening your eyes, you walk through, and you are tasting the vineyards, and you get a real understanding of the quality of the fruit that you get out of that block - on this side, on that side, within a row, this block compared to another block. What you are getting are all the components that you ever need to make very balanced and very exciting wines in the winery. One of the tricks, and something that we have gone down a very long road on, is figuring out how those components then fit together to make our dry Riesling, or semi-dry, in the single vineyards. That's, for me, the continuing evolution, to look at the vineyard's site and say, "What quality can I get out of that?"

What is in the future of the Finger Lakes?

The future of the Finger Lakes is in Cabernet Franc, in sparklings, certainly in continuing to get better at Riesling. We are good at Riesling and I think that we have become, as a region, very well-known throughout the U.S. as a high quality Riesling producer. But, I think that internationally we can get into new markets. I think that the sky is the limit, at the moment, in terms of what the potential of the region is. I think viticulturally and vineyard site wines are the two areas we have to really improve on. That's not a critique of where we are, but that is what we need just to get to that next level. It's the viticulture and choosing the right sites, with the right varieties.

So, how did Hermann end up in the United States?

It's very funny. Hermann came to the U.S. and was working on Hemlock Lake for a monastery. It was a post-education internship that was a one year internship. When he was finished with the internship, he went back to Germany and Walter Taylor had tracked him down, because he knew that there was this young German working in the region. That's what brought him back here to work at Bully Hill. It's a great story and Hermann tells me all of the time how he ended up here.

Monastery? How did he get involved with the monastery?

Through the Vatican.

Read the feature story on how three Michelin star Eleven Madison Park collaborated on a wine with Hermann J. Wiemer.