Quests are fascinating, especially when they are grand. Watching someone hell-bent on achieving something large, something significant, something extremely difficult and risky, engages us on a primal level. The effort, especially over years, banishes the regretful coulda-shoulda-woulda that is the easier path too many people take.

The exception, then, is exceptional.

Meet Angela Scott, 44, who hopes to become the first Black Master of Wine in the world. The Institute of Masters of Wine, the London-based accrediting organization, says that with its newly announced 2020 class, there are only 409 people worldwide who have that elite title. They are “consultants, winemakers, buyers, shippers, business owners, retailers, academics, sommeliers, wine educators, writers, journalists and more,” according to the institute’s website. The exam that leads to that title was first given in 1953.

Scott grew up in Gulph Mills, Pa., with parents who drank wine occasionally, but were really passionate about food. “It drives my dad crazy to this day that my mother and I will sit at breakfast talking about what we intend to eat at lunch and dinner. We love to cook and talk about food. My first independent wine experience was as a teenager as an exchange student in Spain. Drinking wine with my host family was mind-blowing because it really enhanced the food and vice versa,” she wrote Dottie, who first interviewed her by email from New Zealand for Beverage Journal and SevenFifty Daily.

(Angela Scott, photo taken by her husband, Rob MacCulloch MW)

Scott had other deep interests before settling on wine. After studying Art History and Romance Languages at Dartmouth, she thought about becoming a diplomat or a curator and scored a fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. There she worked under Lowery Stokes Sims, a curator and expert in African, Latino, Native American and Asian-American artists, who was later the executive director of the Studio Museum of Harlem as well as an adviser on the memorial for the World Trade Center.

When the fellowship ended, Scott joined the Peace Corps in Haiti and decided upon returning that she could accomplish great good as a lawyer. At the University of Miami School of Law, she discovered that she especially enjoyed business classes and so ended up practicing securities litigation for a Miami firm and then one in Washington, D.C. There, she joined a wine club that organized tastings at embassies in the city. “Tasting Carménère for the first time at the Chilean Embassy was an amazing way to learn about a new grape,” she told us.

Later, she practiced human rights law in East Africa and Central America, traveling from her home base in D.C., but began thinking she was not living her best life. After some serious reflection, she stepped away from that and moved to Napa and wine, which had brought her much joy.

She studied in 2014 at the Culinary Institute of America with Karen MacNeil, author of The Wine Bible, who later hired her to be a tasting coordinator. And Scott continued to take classes while working part-time for Round Pond Estate, which we visited a year ago when it hosted a Premiere Napa Valley tasting.

Beth Novak Milliken, president and CEO of her family's historic Spottswoode Winery in Napa Valley, also hired Scott parttime to be its hospitality manager and cheered her plan to pursue the MW after she earned the Wine & Spirits Education Trust diploma.

The Master of Wine certification is regarded, the institute states, as “the highest standard in all aspects” of wine. It is the pinnacle. “I like being challenged and loved the vastness of the study of wine. It never ends. I thought, perfect! I don’t ever want to stop learning,” Scott told us.

“If anyone can do it, she can – she is, indeed, very determined, and she knows how to study and get through,” Milliken wrote us, noting that Scott has a law degree. “If one can get through that level of minutiae, I think she is uniquely qualified to achieve this.”

To be accepted as an MW student, an applicant must have completed the WSET Diploma or have obtained the Master Sommelier designation, which focuses more on hospitality and service, or have earned a degree in viticulture and enology. Among other requirements, the institute also requires a recommendation from an MW or “another well-regarded wine professional.” MacNeil recommended her. “She’s very sweet and very smart. It was a pleasure to help her,” MacNeil told us.

Working at Spottswoode in 2016 was a harvest intern named Rob MacCulloch, who had become a Master of Wine in 2014. He and Scott hit it off and when he got a job in Napier, New Zealand, as the winemaker and general manager of Portside Wines, she went with him. (MacCulloch wrote a piece about the rollercoaster-like ups and downs of the early days of COVID-19 there for Jancis Robinson’s website.) They figured it would be a good place for her to prepare for the strenuous MW protocols, which involve traveling to other wine regions and tasting broadly at her own expense. “In addition to fees paid to the IMW, you will need to factor in the costs of travelling to seminars, course days and examinations as well as the purchasing of wines for personal tastings and study,” the institute’s website advises applicants, adding that some scholarships are available.

Scott was accepted into the program in September 2018 and paid its $6,000 tuition, which covers, among other things, four “course days” and a one-week “residential seminar.” The Stage 1 test involves a blind-tasting paper on 12 wines and two theory essays. The residential seminars are offered in Europe, Australasia and North America. Scott attended the course days in Sydney and the seminar in Adelaide, but “many people opt to travel to regions outside of their home base to get exposure to additional wine regions,” Scott told us. “Tuition also covers the review of 6 practice essays and 3-4 Research Paper proposals,” the paper being the final piece of required work, Stage 3.

During the residential seminar, she won an award, “a lovely bottle of Bollinger,” she wrote. And in January 2019, she and MacCulloch got married. MacCulloch is a supportive husband, but Scott is adamant about becoming an MW on her own. The institute says it takes a minimum of three years, but most people take longer.

How grueling is the work? Here’s how Scott tells it: In March 2019, she traveled to San Francisco to visit family and to attend a Tre Bicchieri tasting, “then went to Bordeaux for the Stage 1 student trip. Then met up with friends in Alsace then headed to ProWein and then more wine region visits (S. Mosel, Rhineland & Pfalz) traveling through Munich, Prague and ultimately the Wachau & Vienna. Flew directly to Sydney for Course Days 3 & 4 in early April. Spent mid-April to late May preparing for Stage 1 Assessment which is a one-day mini MW exam. Sat for Stage 1 Assessment in June 2019.

“More people than I realized do not make it through. There are three possible outcomes. Clear pass. Re-do Stage 1. Kicked out of program.

"Was informed that I passed first year assessment in August. Yay!

"The whole process began again in September 2019 but for Stage 2 -- pay tuition, attend course days in late October in Sydney, attend seminar in Adelaide in November. Luckily, Rob and I decided that it would make more sense in preparing for the REAL exam this year (2020) to stay in NZ rather than go to Vinitaly or return to ProWein because we needed the money to buy practice wine (and pay rent…etc.) The way things turned out with the pandemic, I could have been stranded and not able to get back to NZ.

"The REAL exam is the notorious four-day wine geek holy grail.”

She was set to take the Stage 2 exam, a two-parter, in June when they were canceled because of the pandemic. Another $6,000, we asked? “Yes. Tuition is about $6KUS every year of the program plus another $2K to sit the Stage 2 exam. So it would have cost $8K this year even before all the wines and any travel. Some people spend $100K on all of this. That will NOT be me. It’s why I took the time out from work to maximize chances of passing in one go. It’s rare but not impossible." According to a spokesperson, the institute is reworking its fees in response to the economic hardship caused by the pandemic.

“I am pursuing the MW because I love to learn. The syllabus for the MW is insane. It covers everything from viticulture to ethics. It is nerd paradise,” Scott wrote. “I am also pursuing it for credibility. Since I changed careers, I sought out formal education because unlike White counterparts I do not receive the presumption of belonging – as Black people we must prove ourselves over and over again.

“To some extent, credentials help. While it’s encouraging that the industry seems to be taking a closer look at deep seated biases, we have not advanced far enough for people to be afforded the same opportunities simply based on their abilities and enthusiasm. We will always be asked for credentials where others are presumed qualified.”

When Dottie reached out to the institute to ask if Scott would become the first Black Master of Wine if she successfully completes the program, Lisa Granik, a co-chair of the institute's Diversity, Inclusion and Transformation Committee, wrote, “The most accurate way to state this is as follows: If Angela successfully completes the program, she could become the first Black MW. Part of the issue is that the timing for any student is never set in stone. Thus, there is the possibility that another student who identifies as Black -- who might not even be in the program yet -- could conceivably finish before her.”

Scott told us: “I’m hopeful that I’m going to pass this thing but I know that nothing is guaranteed. It’s not going to make or break my life either way. I want to encourage others to jump in and take the chance as well.”

We asked how she would use the Master of Wine designation if she got it. She wrote back, “I’d like to work on the business side with a focus on brand acquisitions (this is why I’d like to look into the topic of valuation factors). But the MW journey is so much more about growing through the process itself. My aim is to improve my overall skill set by testing my knowledge of a huge cross section of issues affecting the industry. It sounds so cliché but this is really about the journey -- soaking up as much as possible from this very unique experience.”

Even after they successfully complete the program, students cannot affix the MW after their names until they sign a code of conduct. It “requires MWs to act with honesty and integrity and to use every opportunity to share their understanding of wine with others.” That is an excellent requirement, one that, if upheld by all industry professionals, could go a long way to making the wine world a far more inclusive place.

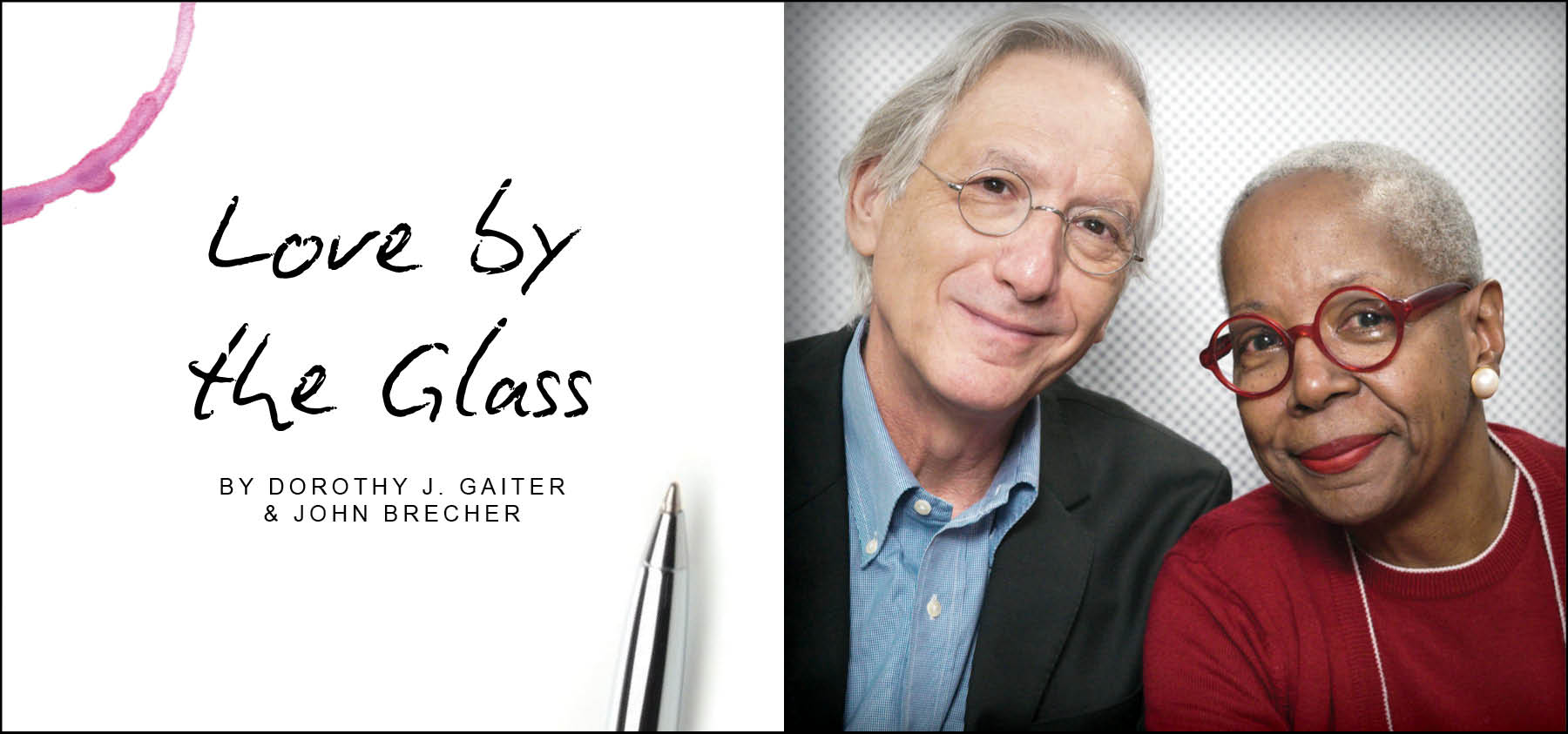

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner art by Piers Parlett