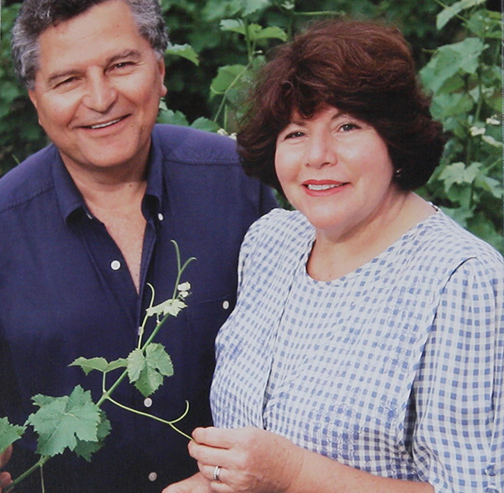

Paumanok Vineyards was founded in 1983 by Ursula and Charles Massoud. The 127-acre Paumanok estate makes Chardonnay, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot but it is Chenin Blanc that is the real star. Paumanok is the only Long Island winery to currently grow the grape. Eric Asimov in the New York Times has described their Chenin Blanc as: "Year in and year out, this is one of the best American chenin blancs around."

Today the winemaking on the estate is run by Kareem Massoud, the son of Ursula and Charles. Grape Collective talks Long Island Chenin Blanc with Kareem Massoud.

Christopher: Kareem, how did your family get into the wine business?

Kareem Massoud: My family got into the wine business through my parents' heritage. My mother was originally from Germany, from the Pfalz. That played a big role in my parents falling in love with the idea of becoming vintners themselves. My father was born and raised in Lebanon, where he and his family enjoyed a lot of fine wine. My father spent time in France, and became very much a Francophile, enjoying French wine and gastronomy. They always had a dream to get into an agrarian lifestyle. They realized what they really would love to do is to become vintners themselves.

When did they decide that Long Island is where they wanted to make wine? And this specific part of Long Island? How did that whole thing come about?

The way my parents ended up here in Aquebogue, on the North Fork of Long Island to plant their vines, to get to that story we have to rewind a little bit, and talk about how my father first made wine in Kuwait, which is a dry country, both literally, it's a desert, but also it's illegal to actually buy alcohol in Kuwait. My father says he had to make wine out of necessity. He would buy grapes at the market and bring them home, and ferment them, and make wine. That was his first experience actually making wine, and what he was doing in Kuwait was working for IBM. He started his family there with my mother. I was born in Bahrain, and then my parents moved, my father got transferred to New York with IBM. My parents bought a home in Connecticut, where we grew up. By this time it was the mid-to-late seventies. My parents read an article in the New York Times about Alex and Louisa Hargrave, who were really the pioneers on Long Island.

They had already been thinking in the back of their mind, perhaps they could look for an existing property in Germany to plant the vineyard. What with my mother's relatives still being there, but my father wasn't ready to walk away from his career at IBM. They said, "Perhaps we can do this in our own backyard." They came out, they met the Hargraves, and basically fell in love with the North Fork, and then within a few years, by 1983, is when they finally closed on this property, where we are right now. In 1983 they planted our first Riesling and Chardonnay grape vines.

Kareem, your father was working at IBM, he met the Hargraves, he saw this piece of property, and then what happened?

After my parents met the Hargraves, they really caught the bug, so to speak. They thought, "You know, we don't have to move far away, we might be able to do this in our own backyard." They lived in Connecticut at the time, and they just fell in love with the idea of being able to grow fine wine in New York City's backyard, on the east end of Long Island. By 1983, they closed on this farm and planted our first grape vines. For the first six or seven years we were just grape growers, and then by 1990 they renovated and rebuilt what used to be a turn-of-the-century potato barn. Since 1990, we've been an estate winery, doing everything here. We plant the vineyards ourselves, we do all the vineyard work, the vinification, and the bottling, it's all done here. We're a true family estate winery. We grow eight varieties, Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Petit Verdot.

How did Long Island become a grape-growing region?

The modern history of Long Island wine really goes back to the early seventies when the Hargraves were the first to start, and then there were a few other pioneers who came after them, including my parents, and the conventional wisdom then is more or less still the same now, which is, Long Island being an island jutting out in the Atlantic, and being surrounded by the Atlantic, Peconic Bay, and Long Island Sound is very much a maritime climate. If you look at a globe and draw a line around the globe, you'll see that where we are on the 43rd degree of latitude coincides with some other great wine districts around the world.

We have the most in common with Bordeaux, and that, I think, was part of the inspiration for the industry here. If you look at the parallels that we have with Bordeaux in that it's a maritime climate, the soils drain extremely well, which also explains why the topography being primarily flat is actually okay, whereas otherwise it may be less desirable. Since the soils drain so well, we're not as concerned about drainage as far as being on a slope. Then we have the fact that we're a cool climate, which allows us a long ripening period, because of the maritime climate. The maritime climate acts as a season extender. When the bodies of water warm up during the summer, they retain their heat and act as a heat-sink. September and October, it can be unusually warmer here, and in fact the day of this shoot is November 2nd and you can see I'm wearing just a shirt. That's not uncommon out here. That's key to having a slow, but thorough and complete ripening of the grape.

Talk a little bit about the terroir in Long Island.

So the terroir in Long Island can really be defined by the prevailing soil type, especially on the North Fork, which is a sandy loam with sandy, gravely sub-soil. Long Island was created during the last Ice Age. When the glaciers receded, they left behind a moraine field, and we have this alluvial profile to our soil. The key point is that they drain incredibly well. Even after a rain event where we might get two or three inches of rain, let's say, you go out after the storm, and you rarely see any standing water in the field. If you see any ponding or puddling, it's usually wherever there might be ground-compaction. In most fields you won't see any standing water. It's like a giant sieve. The soils drain extremely well.

Then, the climate is really defined by the maritime aspect of the climate, where we have these bodies of water, Peconic Bay, Long Island Sound, and the Atlantic Ocean, which act as air conditioners in the summer, and as heat-sinks in the fall, where they really act as season extenders. They elongate our growing season, because they provide a little bit of extra warmth at the end of the season. On the other hand, the beginning of the season is delayed because these bodies of water are holding all the cold temperature from the winter. Which is kind of a blessing in disguise, because that provides some insurance against the spring frost. Since the growing season is starting later, it gets you usually into a safety zone as far as being frost-free.

Talk about some of the issues with vintage variation in Long Island. What are some of the issues, and how will one vintage be different from another, mostly in terms of crop yields, the ability to make wine, and also in terms of some of the profiles of the wines.

As far as vintage variation, we certainly do have vintages on Long Island that we can see a fair amount of variation from one to the next. That's entirely attributable to the fact that weather patterns can vary quite a bit. We have flowering usually in mid-June. The weather in mid-June can be very variable, where it can be sunny, breezy, and dry, which is ideal for flowering. It can also be muggy, and calm, and foggy, and sometimes you have all of the above, plus some rain, and that makes it very difficult for flowering. For the most part we usually, more often than not, have good to above-average yields.

Then, our biggest challenge on Long Island is the perennial humidity. We do get humidity on more or less a perennial basis. The question is not if we'll have it, but how long it will last. Sometimes it's just two or three weeks in July, sometimes it's more like six weeks or more starting in June and getting into August. Usually by the end of August the humidity has abated, and we get some beautiful blue skies, sunny, dry, breezy weather with cool nights as we move into the end of summer.

Do you have a philosophy of viticulture?

Our philosophy, when it comes to viticulture, is really we have two points of orientation. One is that you can not manufacture great wine, you have to grow it. There's no substitute for healthy, ripe fruit. The only way you can make great wine is by starting with the healthiest, ripest grapes obtainable. With that big overarching goal in mind, to grow the healthiest, ripest fruit we can, we really try to stay focused on the goal, and allow the method to be incidental to the goal. In other words, to put it in a soundbite, we describe our viticultural techniques as sustainable. We are a part of the Long Island Sustainable Wine growing organization, which is actually a certified program.

In a nutshell, like I said, we try to remain focused on the goal, and we're open-minded about the method. We're open to different methods of viticulture. The most important thing is to start off with healthy, ripe fruit. You can't make a great wine without healthy, ripe fruit. No matter how well-equipped you are. No matter how you may or may not want to manipulate a wine. You can't manufacture great wine, you have to grow it.

Now talk about your philosophy of winemaking. Once you've got the fruit in, and you're bringing it into the cellar. How do you approach that?

As far as our philosophy with winemaking, it's very simple. Like many producers around the world, as winemakers we view ourselves as custodians of what we got from Mother Nature. I believe it was Galileo who said, "Wine is bottled sunshine." You get this gift from nature, and we've worked very hard with Mother Nature, as my father likes to say, "Winemaking is less of an art, and more of a partnership with Mother Nature. Unfortunately, she's the senior partner." When you get this fruit that you've been given from a wonderful season, it's your job as the winemaker, your fundamental responsibility, to preserve it, and keep it protected, and get it into the bottle without any diminishment of what characteristics it had to begin with, and to just guide it along its path. Very minimalist approach, and in fact we have a whole range of wines that we call 'minimalist.' In general even for our mainstay Paumanok labels, the winemaking approach is a minimalist approach.

People say that Bordeaux varietals are the ones that perform best in Long Island. You've been growing grapes here for a long time. What varietals are you excited about? What varietals do you feel really represent the climate and the soils here?

On Long Island, there's been a lot of talk about the Bordeaux varieties, and the Bordeaux varieties grown on Long Island have had a lot of acclaim over the years. We continue to grow, and to be very pleased with what we're getting with the Bordeaux varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cab Franc, Petit Verdot, are the four Bordeaux reds that we grow. We also grow Sauvignon Blanc. We've also been very happy with the Loire varieties, we're the only winery in New York growing three Loire varieties. We grow Chenin Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc, and Cabernet Franc. They all clearly do well in the vineyard, and they all really make nice wines.

Then, finally, we also have Riesling, which is a bit of an homage to my mother's heritage being from the Pflaz. Riesling has also done very well for us over the years. If you asked us to tear out one of these eight varieties, we really wouldn't know where to begin. We're happy with all eight of them. We're not ready to hang our hat on a single variety. We like to celebrate the fact that we can do a number of things well. If anything, we might look into planting some additional varieties in the future.

For example, I mentioned the Loire varieties, of all the Loire varieties, the one that might make the most sense on Long Island is Melon de Bourgogne, which in the Loire Valley is grown in Muscadet, which is the district that's closest to the Atlantic over there. Given our maritime climate, it would be interesting to experiment with that. We've thought about varieties like Albariño, of which there are now a couple other producers out here who are experimenting with Albariño. We may still consider that in the future. Something like Malbec is also definitely of interest, that's another Bordeaux red variety, and there are some others who have done well with it here. There are a couple of others that may be of interest over time as well. Pinot Noir for sparkling wine. We already make a blanc de blancs from Chardonnay.

Then, there are some things like Dornfelder, or Blaufrankisch, which are also a bit of an homage. You see some varieties like that grown in the Pfalz where my mother's from. There are also some examples here that have also done well.

First start with when you took over from your father in terms of the winemaking. Were there any new ideas that you had, or were you focused on maintaining what he had started? How did you approach that transition to becoming the primary winemaker?

I'm a second generation winemaker at Paumanok. I learned from my father, who's the founder and owner of the winery, together with my mother. My father's been my mentor. I really learned from him. I really got into the hot seat, as far as the winemaking, starting with the 2001 vintage. Since then my father and I continue to collaborate on an executive level. I still do the hands-on work, and as far as the winemaking, my father and I very much share the same general philosophical approach; to have the fruit that we get from the vineyard transcend into the bottle as an expression of the terroir, what we would call 'vin de terroir.' That's been our approach from the beginning; to make wines that are charismatic and reflective of the terroir, and above all that are delicious wines that pair well with the local gastronomy that we find here on the East End of Long Island.

We talked a little bit about vintage variation in a generality, but from year-to-year, how do the wines change? I've had your Chenin, which is a delicious wine, and they do seem a little different sometimes from year-to-year. How is that? How is the vintage variation?

When we talk about vintage variation with our wines here at Paumanok, and in Long Island in general, it has everything to do, as in most cases, with the weather that season. We'll have some summers where we simply have significantly more heat. Where you are going to have higher alcohols, lower acidity, and stylistically that can make a dramatically different wine. That said, it's not unlike elsewhere. We have typical vintages, where we can say typically, our whites are in the 11 to 12, 12.5 percent alcohol range. Even 13 depending on the variety. The reds are more like 12 to 14. If you look at the import labels from Bordeaux today, and in the past, they would say 11 to 14 percent, just to cover themselves. We could use the same label on Long Island wines if we were exporting them and they required a range of alcohol.

There certainly will be years where the wines are going to be a little bit more alcoholic, a little bit more full-bodied and lower in acidity. Typically, they're going to be more moderate, have good acidity, good varietal character, but there's no question. We have vintages where one season Mother Nature is smiling on you with a lot of heat and sun, blue skies, cool nights. 2013 was as close to ideal of vintage as we've had. That's one recent vintage as an example. Then, we have a vintage like 2016, which is the year that this is being recorded right now, where it was a good vintage, but in comparison to '13, there was a little bit more humidity, a little bit more rain during the vintage, and it's been a little bit more challenging, but still a good vintage.

Fantastic. Is there a big difference from year-to-year in terms of your yields? How much wine are you making, and how much does that vary?

As far as our production and year-to-year variation in production, we've been hovering around 10,000 to 12,000 cases a year. Yeah, it has varied basically from 10,000 to 12,000 cases a year over the last few years. That's a combination of the yield that we get from the vintage, and natural causes, so to speak, whatever Mother Nature's giving us as far as fruit set. We're also planting new vineyards, we're rejuvenating old vineyards. In some cases we're ripping out and replanting older vineyards. That will obviously also impact the total size of the harvest.

(Banner art by Piers Parlett)

Read Eric Asimov in the New York Times on American Chenin Blanc

More on Long Island wine:

Miguel Martin at Palmer Vineryards

Barbara Shinn and David Page of Shinn Vineyards