Count Laurent Bernard de la Gatinais admits that having the title of a French nobleman doesn’t hold much sway these days. But on a personal level it means a lot to him. “Every morning when I look at myself in the mirror I want to be proud,” says the owner and winemaker of Sicily’s Tenuta Rapitalà. “Not just for what I do, but in the way that I do it — the way my parents taught me and their parents taught them. For me, it’s a code of honor.”

Laurent’s French father, Count Hugues Bernard de la Gatinais, met his Sicilian mother, Gigi Guarrasi, at a party in France in the mid-1960s. Three years later, they were married and living in Sicily where they had inherited the Guarrasi family estate that had been destroyed by a powerful earthquake. They rebuilt the winery, planting indigenous Sicilian grapes along with some of their favorite French varieties.

Fifty years later, Laurent is continuing to make wines that are a pure expression of the distinct Sicilian terroir combined with an elegant French winemaking style. Grape Collective sat down with Laurent to talk about the rich mosaic of cultures in Sicily — a land of contrasts — and Tenuta Rapitalà’s place in it.

Lisa Denning: Thank you for joining us today Laurent.

Laurent Bernard de la Gatinais: (laughing) I am half Sicilian so I don't know if I will answer too many questions. My French half will answer though, so don't worry.

Thank goodness for your French heritage! Can you tell me a little bit about your background and the history of the winery?

The history of the winery is a family history. It was my mother’s family estate since around 1800 but in the end, it’s due to a schoolmate of my mother’s who didn't pass his last high school exam. His parents — they were good friends of my grandparents — said to my grandparents, “We already paid for a trip in France but he has to repeat the exam so if you want to send your daughter to France with us, the trip is already paid.” This is how my mother, when she was 18, ended up meeting my father in Northwest France.”

My paternal grandfather was a winemaker, but he passed away when my father was young. My father entered the military and became an officer in the French Navy. He would often pay visits to his uncle who would have many guests at his home in the northwestern part of France. One time, he entered the living room and said, "Uncle, who is that nice girl near the fireplace?" The uncle said, “She is from Sicily, don't even dare to speak with her." Lucky for me, my father didn’t listen to him and after three years they got married in Rome and then she imported him to Sicily in 1968. It goes to show you that you never know where destiny will take you. I'm here because a schoolmate of my mother’s failed his high school exam!

My paternal grandfather was a winemaker, but he passed away when my father was young. My father entered the military and became an officer in the French Navy. He would often pay visits to his uncle who would have many guests at his home in the northwestern part of France. One time, he entered the living room and said, "Uncle, who is that nice girl near the fireplace?" The uncle said, “She is from Sicily, don't even dare to speak with her." Lucky for me, my father didn’t listen to him and after three years they got married in Rome and then she imported him to Sicily in 1968. It goes to show you that you never know where destiny will take you. I'm here because a schoolmate of my mother’s failed his high school exam!

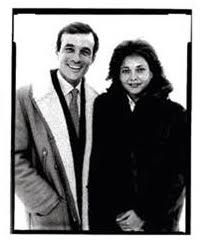

(Photo: Count Hugues and Countess Gigi)

1968 was the year of the earthquake in Sicily and all of the buildings collapsed at the estate and my parents decided to rebuild the estate which is in the Alcamo area — in fact, Alcamo was one of the oldest DOCs in Italy. It’s close to Palermo and Trapani, in the Northwest part of Sicily, on the complete opposite side of Mount Etna.

We were the third winery bottling quality wine in Sicily in the middle of the '70s. We came out in the market as a family enterprise and in 1999 we merged with a group called GIV, Gruppo Italiano Vini, the owner of Italy’s largest collection of wine estates. We were seeing what was going on in this market and we saw that you need to have bigger shoulders for the economics of winemaking and especially to reach the foreign market. I like to say I was born with the wedding of my parents and I was reborn with a civil union between me and the GIV group.

And nowadays, we are one of the most known and sold Sicilian wines in all of Italy. 75% of our sales are in Italy. If you sell a bottle of Rapitalà here in the US, you can be sure your customers will find it in Italy and you will see that it’s a truly appreciated wine. I'm very proud of that, especially in foreign markets where you don't always find true brands from the place. Many are made for export — made to please, as they say. With Rapitalà, don't worry, you are buying a true Sicilian wine even if it's from a French point of view.

What percentage stays in Sicily?

Half of the 75%. Every region in Italy drinks the wine from their own region.

What about you, did you always think you would be a part of the family business?

I always knew that it would be my summer job, but first I became an engineer. I wanted to become an engineer since I was three years old and I had to be hard-headed to accomplish that. Then I decided to came back to the family business. I thank my parents that they let me be free to choose whether to come back or not.

In a lot of family enterprises, what you see at the changing of the generations is a very critical and crucial moment and if someone does it because they have to or because it’s the easiest way, that’s not good. I made my own decision to come back and now that I’m linked to a big group, if I didn't do my job well, I wouldn't be there.

Where did the name Rapitalà come from?

Where the name came from is lost in time in a sense. In the 9th century, Sicily was conquered by the Saracens who spoke Arabic, so like Mars el'Allah is  Marsala, The Port of God, Rapitalà might have two roots, Rabat or Rabeed. Rabat is land, gardener, so it could mean the garden of God. Rabeed is like more the stronghold of God.

Marsala, The Port of God, Rapitalà might have two roots, Rabat or Rabeed. Rabat is land, gardener, so it could mean the garden of God. Rabeed is like more the stronghold of God.

Are you the first to have introduced non-indigenous varieties to Sicily?

My father, if not the first, was surely one of the pioneers. We started planting French varieties at the end of the '70s when nobody was even dreaming about Pinot Noir or Chardonnay.

What percentage would you say is indigenous versus the French varieties?

Mostly indigenous, afterall, we are a Sicilian brand. But our wines are made from a French point of view in the sense that they are more elegant, more balanced. The estate is 550 acres all in one block from 1,000 to 2,000 feet, exposing north. We start the harvest around the 10th of August, more or less, and we end it at the 10th of October. Then we do a late harvest that we pick in November. Three to four months of harvesting the same place! It's unique in the world.

Why is it done like that?

Because of the altitude. It’s amazing how just 1,000 feet of difference can delay the harvesting. For example, Catarratto, a typical white indigenous variety can have one month of delay from the bottom to the top.

I haven't found a lot of places in the world where you have this long time of harvest. Sicily is really a continent in miniature, so harvesting in the south begins at the end of July but in Etna you're still harvesting during October. I like to make a parallel comparing the wine to athletes that are running the marathon. I don't care which one goes the fastest and wins. I just want everybody to arrive to the finish line. The challenge is to understand how to train them. The backpack they can carry, and how they carry this backpack to the end of the finish line will determine the results.

Tell me a little bit about the different grape varieties you grow and the terroir.

Our terroir, technically, is all clay. The more you go up, the more sand you usually find in the clay. We also get a very nice difference between day and night temperatures. It's like the French concept where they have a certain zone divided from one vineyard to the next. We began to recognize over the years that certain places are different, even if planted with the same variety. For us, we call it a parcel. It’s not just the exposition, altitude, micro climate, but even the agronomical technique used to build it. The 550 acres of estate are divided into about 150 parcels.

Our terroir, technically, is all clay. The more you go up, the more sand you usually find in the clay. We also get a very nice difference between day and night temperatures. It's like the French concept where they have a certain zone divided from one vineyard to the next. We began to recognize over the years that certain places are different, even if planted with the same variety. For us, we call it a parcel. It’s not just the exposition, altitude, micro climate, but even the agronomical technique used to build it. The 550 acres of estate are divided into about 150 parcels.

It's not easy to cultivate vineyards in Sicily because we have too much sand and a low amount of water and so much heat in June, July and August. If you compare Sicily to the North of Italy, for example, we do less than half the average production they do, so in Sicily we produce a low amount of grapes per acre.

Let's talk about sustainability and what you’re doing at the winery in this regard.

We just started the conversion to organic and in three years we will be certified but we’ve been cultivating in the organic way during the past two years. I think for us it’s been a natural evolution of our way of farming the vineyards. During the past ten years we started doing things like planting other crops, fava beans for instance, which help in many ways to keep the vines healthy. We also have introduced pheromones to sexually confuse the insects. They go a little crazy but then they don’t damage the vines.

I don't think you can find another estate in Sicily changing 550 acres in one block to organic. Because bureaucratically you have to go through all the different paperwork, this, that, and the other thing. You have to declare when you start and to be subject to controls and in three years you can be certified.

Additionally, we use a lot of technology, like sensors in the fields that link to software, enabling us to determine the probability of the development of illness, or insects for example. We use infrared photos that give us the map of the more vigorous parts, so we know where to give nutrients and where it’s not necessary.

For us, our philosophy in the field, the vineyards, and in the cellar, is that the less you do the better it is. Prepare the condition to let the process flow in the direction you want. Any adjustment is something that if you prepare well, you won't need.

Is that your philosophy of winemaking?

It's a philosophy which you need to know how to not do anything.

You do a lot in order to do nothing!

Absolutely. I remember an agronomist, a few years ago, worked with us and was doing very well. He was working on the cultivating and he came to me and he was very proud of his job. I said to him, “Yes, you are lowering the time and the cost of everything. Now you have to learn not to do anything.” He looked confused and said, "What?!" I think he spent the worst week of his life trying to understand what I meant!

What changes have you seen in Sicilian winemaking in the past 40 years?

As Rapitalà we belong to the first oenological revolution of Sicilian wine. At that time, early in the seventies, there were just 3 main bottle producers: Duca di Salaparuta/Corvo, Tasca d’Almerita/Regaleali and us, Rapitalà. The main difference compared with the past was the use of cold vinification, soft presses and new vines being planted, both indigenous and French. During the '70s was the first winemaking revolution where quality wines started to be made and finally people became aware of Sicilian wines.Then in the eighties Donnafugata was born then Planeta in the nineties, etc.

In the early 2000s, we saw the second revolution of Sicilian wines. An explosion of producers, little and big ones. New winemakers came to Sicily and we saw the growing of very good young Sicilian winemakers. We can say that in the last 40 years we saw the transformation of Sicily as a real mosaic of wines. We finally saw a renaissance of wine in Sicily. It has become a modern, trendy region with a fantastic offer in terms of diversity, quality, know-how in vinification and vineyard cultivation.

What are the different styles of Sicilian wine being offered to the consumer these days?

If you like the style of Californian wines, go to the south of Sicily. If you like extremely mineral wines, there's Etna. If you like elegance, come to Rapitalà. Everybody will find his own wine. What is nice is that even in one area, you have hundreds of interpretations of a grape because of the style of the producer and because of where it grows — higher, lower, south, west, north — so many different styles.

Sicily is split with the European area and the African, so the soils are a composition of the two. It is really squeezed between the two. The Northern part is from the European area. The Southern part is from Africa. The diversity, the richness you can find in Sicily you cannot find everywhere else in the world. It's in everything. I call it the Land of Contrasts. It's a mosaic. There's something for everyone. There's a taste for everyone and there's a terroir for every single one. All of our labels are as pretty and as colorful and they represent this mosaic of what is Sicily. Mosaics are in Sicily both an art and an architectural form. They are in our history.

Even with Sicilian food, It's one of the richest mosaics of cuisines you can find in Italy. Everybody passed through, historically. When you visit Sicily, the richness is from every denomination — the Arabs, the Normans, the Romans, the Venetians, the Greeks, everybody. The Mediterranean sea was the center of the world for commerce throughout thousands of wars. The richness you find in Sicily, in history, in architecture, in food and in wines, can be found nowhere else in the world.

I’ve never been to Sicily and I would love to visit.

Take at least one week because it's quite huge to visit. We have so many things to see that I think no matter how many times you visit, you'll see something new, something different, even in the same city. I live in Palermo. There’s one million inhabitants. It’s the largest city, the capital city of Sicily. You can spend one week just there in Palermo. The only problem with Sicily is that you can become addicted to Sicily, absolutely.

I could end up moving there like your father did!

Absolutely.

What kind of wine do you like to drink when you're not drinking your own wine?

I like to drink everything. Of course, I love Burgundy wines, Puligny-Montrachet, Nuits-Saint-Georges. I also like Californian wines and Pinot Noir from Oregon. I like to taste different wines from different parts of the world. It's very interesting and, especially nowadays, globalization means that you have to be aware of what is going on all over the world. I like that. It's always an experience. Also, in every moment of your life, your taste changes. Fifteen years ago I was fan of big, red wines. Today I'm more into dry, white wines.

And from your own wines, if your cellar were under water, which bottle would you dive in and save?

I would try to organize a rescue for every bottle.

You don't want to settle for just one — you want to save them all!

As an engineer, I cannot save just one so I would plan an entire rescue for them all, like a Titanic rescue.

If it was your last meal on earth, what would you have to eat and which wine would you pair with it?

I would need to spend a lot of time to decide since it would be my last meal and because it would depend on my mood. Even if someone asks me what my favorite wine is amongst my own, I say, "Well, it depends on my mood and it depends on what I’m eating." I like to cook too. I conquered my wife by cooking. The only problem is she doesn’t gain weight. I take the weight!

That's not fair.

You’re right, it's not fair. I have a good friend of mine who once told me that I eat everything that doesn't bite me first. I like to try different things, different cuisines, from Sicilian to Chinese to whatever because I think that cuisine is an expression of the culture. If you want to really understand people, try their cuisine, the way they cook, the way they prepare the food. It's a measure of their culture. The richness in the cuisine is a measure of that.

Read more from Lisa Denning on Grape Collective and The Wine Chef.