When Canadian Matthew Chittick moved to Bourgogne in 2011 to start his winemaking journey, he worried about being accepted by the local vignerons.

“I was thinking, ‘I’m only 29. How will I talk to people with 30 years of vineyard experience?’” he said. Fortunately, things worked out well, and not only have he and his Parisian-born wife Camille successfully founded Maison MC Thiriet, they’ve also formed many lasting friendships.

The French wine region of Bourgogne, widely regarded as the benchmark producer of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, frequently attracts ambitious, young winemakers from across the globe to its alluring terroir. However, the area is steeped in centuries-old winemaking traditions, and wineries are typically handed down through the generations. New arrivals have a hard time finding property for sale, and if they do, it doesn't come cheap.

The French wine region of Bourgogne, widely regarded as the benchmark producer of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, frequently attracts ambitious, young winemakers from across the globe to its alluring terroir. However, the area is steeped in centuries-old winemaking traditions, and wineries are typically handed down through the generations. New arrivals have a hard time finding property for sale, and if they do, it doesn't come cheap.

The price per acre of vineyards starts at around $70,000 on the lower end and reaches staggering figures in the millions throughout the renowned Grand Crus. According to Safer, a French land acquisition firm, a single hectare of vines in the Côtes d'Or averaged about $7 million in 2020, a 4% increase from the previous year.

Nevertheless, success stories are not unheard of. Some newcomers, without familial vineyards or generational expertise, are able to navigate the intricate process of finding, buying, and establishing their own wine estates. During a recent visit to the region sponsored by the Bourgogne Wine Board (BIVB), I met three young winery owners, including Chittick, who have established new estates in a place where vineyards have long been synonymous with lineage. These next-gen winemakers, driven by passion and, perhaps, a bit of luck, are joining their Bourgogne-born peers in crafting wines with a sense of place while safeguarding the land for future generations.

Domaine La Croix Montjoie

One tale of success is that of Domaine La Croix Montjoie in Vézelay, a beautiful village in Bourgogne’s north-central area, about 60 miles northwest of Beaune. The estate, founded in 2009 by Sophie and Matthieu Woillez, draws its name from a cross situated at the juncture between Vézelay and Tharoiseau, part of an ancient pilgrimage route.

One tale of success is that of Domaine La Croix Montjoie in Vézelay, a beautiful village in Bourgogne’s north-central area, about 60 miles northwest of Beaune. The estate, founded in 2009 by Sophie and Matthieu Woillez, draws its name from a cross situated at the juncture between Vézelay and Tharoiseau, part of an ancient pilgrimage route.

Vézelay is an appellation known for crafting high-quality, affordable, Chardonnay-based white wines from its clay-limestone soils. The clay contributes to the fruitiness and roundness of the wines, while the limestone imparts a minerality reminiscent of the more famous Chablis. Domaine La Croix Montjoie produces about 120,000 bottles annually of AOC Vézelay white wine and AOC Bourgogne Rouge. The Woillezs have, in a short time, become known for diligently producing fresh, mineral-driven wines that represent Vézelay's unique terroir.

The young couple met while studying agronomy and enology in Montpellier, afterward working in Bordeaux and the Rhône Valley before pursuing their dream of owning a winery. Initially, they looked for property in Beaujolais, where Sophie's grandparents had been winegrowers, but found nothing suitable. Turning their attention to Bourgogne, they focused outside the most pricey areas, discovering a Vézelay property with breathtaking views of the Morvan mountain foothills.

“We found ten interesting hectares adjacent to a 19th-century farm that were very low priced for Bourgogne,” said Sophie. “I think sometimes things work out by chance, and we are very happy to be a part of Bourgogne.”

Woillez noted when she and Matthieu first arrived, the local wine producers were watching them to try and understand who they were and how they wanted to work.

Woillez noted when she and Matthieu first arrived, the local wine producers were watching them to try and understand who they were and how they wanted to work.

“As they understood that our arrival was good for the appellation and the vineyards, they became friendly,” said Sophie. “Vézelay is a small appellation that is not well-known like the stars of Bourgogne, and there is not a lot of competition between the producers. Everybody knows each other, and people, like us, who work hard and want to promote good Vézelay wines are welcomed into the close-knit community.”

The young couple has also strengthened bonds with the local community by engaging in village life. “I am an active member of the local and regional tourism offices,” said Sophie, “and the Association of Women and Wines of Bourgogne. Matthieu is very involved in the BIVB (Bourgogne Wine Board) and is President of the Vézelay appellation.”

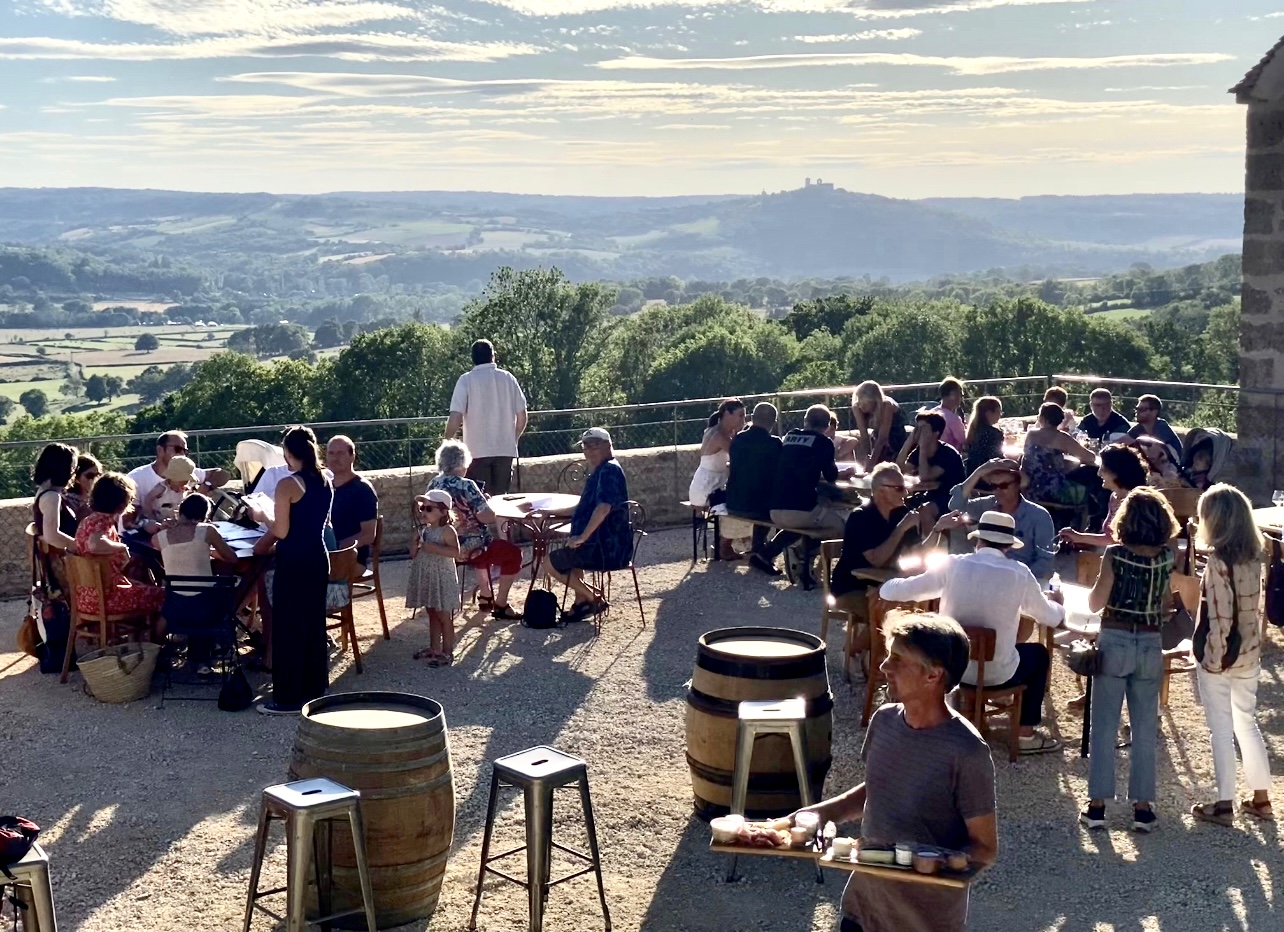

Showing how newcomers often bring new perspectives, Domaine La Croix Montjoie welcomes visitors, a departure from the historical practice of limited winery access in Bourgogne. Tastings and tours are available year-round, with a summertime pop-up wine bar on the terrace which draws those seeking a scenic aperitif.

Showing how newcomers often bring new perspectives, Domaine La Croix Montjoie welcomes visitors, a departure from the historical practice of limited winery access in Bourgogne. Tastings and tours are available year-round, with a summertime pop-up wine bar on the terrace which draws those seeking a scenic aperitif.

Additionally, in keeping with the ethos of the up-and-coming younger generation, the Woillezs are dedicated to the long-term health of their vines and soil. They have been practicing organic since 2018 and certified in 2021, embracing eco-conscious practices despite the difficulties posed by the region’s typically cool and damp climate.

“Vézelay is so beautiful and well-respected that vintners here are trying to farm without the use of synthetic chemicals,” affirms Sophie. “With climate changes bringing more sunshine and warmth, it has become easier. Today, 50% of the vineyards in Vézelay are organic or in conversion, whereas the average for organic viticulture for all of Bourgogne is less than 10%.”

Domaine de La Monette

Adding a unique take on the story is Pierre-Etienne Chevallier, proprietor of Domaine de La Monette in the Mercurey appellation of the Côte Chalonnaise region. While Chevallier is not a newcomer to Bourgogne since he was born and raised in the region, his story is not one of inheritance; he became the first in his family to establish a winery when he acquired an estate in January 2023.

Adding a unique take on the story is Pierre-Etienne Chevallier, proprietor of Domaine de La Monette in the Mercurey appellation of the Côte Chalonnaise region. While Chevallier is not a newcomer to Bourgogne since he was born and raised in the region, his story is not one of inheritance; he became the first in his family to establish a winery when he acquired an estate in January 2023.

Chevallier's journey into winemaking took an unconventional route. “I didn't begin my life with wine, but rather with politics and literature,” he said. “However, I realized I needed to be outdoors, working with my hands, and I've been working in the wine business for nine years now, primarily in production.”

Following a three-month stint in Sonoma, California, Chevallier returned to Bourgogne, where he found work at several local estates. His story illustrates how individuals shaped by international exposure and varied work experiences can thrive in Bourgogne, bringing fresh perspectives to a traditional environment.

The Bourgogne-born Chevallier said that his local origins helped him navigate the purchase of his estate. However, the main reason the community accepted him was his experience in the field. “To be accepted here,” he noted, “it’s crucial to prove that you know what you are talking about. And also, because of my previous jobs, I already knew a lot of winemakers.”

And most important, says Chevallier, is to have a deep understanding of the specific region where you plan to establish a winery. Working at Domaine du Cellier aux Moines, situated in nearby Givry, provided Chevallier with valuable connections in the local winemaking community. Philippe Pascal, the proprietor of Cellier aux Moines and former LVMH executive, had his own sets of hurdles when creating a winery in Bourgogne. Originally from the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, Pascal came from a family whose business was in the textile industry. When he and his wife Catherine arrived in Bourgogne in 2004, they were initially considered strangers, despite Catherine being from Beaune. “It took years,” Pascal told Grape Collective in October 2020, “but once the locals realized that we were seriously committed to Givry, they began to appreciate us.”

Another reason Chevallier says the locals accepted him is his family's involvement in the town's activities. “My wife and young children have become a part of the community,” he says. “We bring life to the village, and we see that people here appreciate that.”

His path was not without its challenges, though. “It has been very difficult to settle as a new winemaker here,” he stated. “Since the demand for vines is so high and the supply so low, prices have become exorbitant. When I purchased my vines, it involved a substantial financial commitment, and I had to borrow a large amount of money. Fortunately, Bourgogne wines sell quite easily.”

Despite the economic pressures of purchasing an estate, Chevallier remains committed to sustainable practices, including organic farming, which requires, among other costs, a 2,000 euro annual fee. Like many other young Bourgogne wine producers, he considers pesticide-free farming integral to a vineyard's well-being and is continuing the estate's 12-year-long history of organic certification.

And, similar to the Woillezs, Chevallier also enjoys hosting wine consumers and industry professionals. The winery offers cellar visits with tastings and tours, and there are plans to convert a building on the property into a tasting room with guest accommodations.

“Many producers don’t want to participate in the time-consuming process of offering guest experiences since Bourgogne wines already sell so easily,” said Chevallier. “I think it’s a bit unfortunate.”

Maison MC Thiriet

Chittick and Thiriet’s story is equally inspiring. The young couple created a boutique negotiant business in 2016 with just four barrels of Bourgogne Blanc and three barrels of Côtes de Nuits Villages. In 2022, with a strong network of grape grower relationships, they purchased a domaine and built Maison MC Thiriet in the heart of the Côte de Nuits. Their gentle, minimalist cellar practices, such as native yeast ferments, manual punch-downs, and minimal sulfur additions, yield light, fresh wines with an appealing purity of fruit. Their goal, said Chittick, is to make wines that can be enjoyed soon after bottling or ten years down the road.

Chittick and Thiriet’s story is equally inspiring. The young couple created a boutique negotiant business in 2016 with just four barrels of Bourgogne Blanc and three barrels of Côtes de Nuits Villages. In 2022, with a strong network of grape grower relationships, they purchased a domaine and built Maison MC Thiriet in the heart of the Côte de Nuits. Their gentle, minimalist cellar practices, such as native yeast ferments, manual punch-downs, and minimal sulfur additions, yield light, fresh wines with an appealing purity of fruit. Their goal, said Chittick, is to make wines that can be enjoyed soon after bottling or ten years down the road.

With their well-crafted wines, Chittick and Thiriet have been readily welcomed into the local community. Yet Chittick notes that Burgundians are, by nature, reserved and can initially seem cold and distant. Still, he says, things can change very quickly with a little bit of effort.

“The wall is very much there in the beginning,” he says. “For example, when you go to a tasting, the winemaker might pour you wines and say nothing, just give you the wine. It's really up to you to be passionate and engaged. When you’re forthcoming and ask questions, a wine producer might then say, ‘Have more wine,’ and they'll pour you a vertical of 7 vintages dating back to 1954!”

Like Chevallier, Chittick pointed out that the best way to foster rewarding relationships with locals is to show them what you’re capable of. “You have to be able to do everything they do, or more,” he says.

While Maison MC Thiriet may not yet hold official organic certification, Chittick and Thiriet’s natural approach to winemaking includes the use of organic and biodynamic viticulture. As newcomers to the region, they particularly feel the responsibility to preserve the natural landscape.

“Burgundy is small, and there’s quite an obligation, especially as a foreigner, to make the vineyards healthier for the next generation.”