Tempus fugit! It’s already time for all of those “the perfect wine for Thanksgiving” stories that make this choice much harder than it needs to be.

For, despite all the merchandising surrounding it, Thanksgiving is an occasion to be grateful for what you already have: like the people you care about and who care about you; about having another day here with them. So we think your wine choice ought to complement the celebratory mood even more than the food, and the perfect wine or wines to do that are those enriched by your personal stories.

One way to achieve that is to buy a wine that means something to you and your family. We’d guess that most wine writers won’t be recommending Korbel, the inexpensive bubbly from California, but it’s part of our history. When John was growing up, and when Dottie joined his family, Korbel was the only wine his father ever opened, and only at Thanksgiving and maybe New Year’s. That was a wine we enjoyed throughout the meal with John’s family because there were so many memories attached to it.

Another way to do this is to open a bottle with meaning for you that has some age on it. We’ve always recommended a well-aged wine for Thanksgiving because the smoother, elegant tastes that come with a well-made aged wine won’t clash with the food or add yet another side dish the way a wine of youth and vigor might. If you are lucky to have some wines stored, share one with special memories – yes, even though Open That Bottle Night is happening in February.

If you don’t have a collection, you will have to deal with a reputable wine merchant to get that wine with your memories. For instance, was your first-ever visit to a winery at Robert Mondavi in Napa, as it was for us? Try to find an older Mondavi, which will surely be delicious with every bite because of the memories.

Wine is magic that way. In a recent post on her blog WineSpeed, the great wine thinker Karen MacNeil wrote: “When I hear people say they want to demystify wine, I say to myself: please don’t, please don’t. To demystify wine would put it on par with every other beverage in the world, and as far as I’m concerned, it is not with every other beverage in the world. It sits apart. In fact, it has set itself apart for at least 8,000 years, and there’s a reason that wine has been the beverage of religion, because of that essential mystery that keeps us all in love with it.”

So much about wine will always be a mystery to us. Part of the mystery, of course, is not knowing what we will find when we open the bottle. Sometimes wines seem to age and become less attractive long before we would expect. But you never know. Here’s something that just happened to us, with a twist ending that we did not anticipate.

In 1992, we visited the North Fork of Long Island, then a new area for wineries. We dropped in on the pioneering Hargrave, the first winery in the region, founded in 1973 (it is now Borghese). It was famous for its Pinot Noir. Louisa Hargrave, who founded the winery with her husband, Alex, was there. She welcomed us and our two young children warmly.

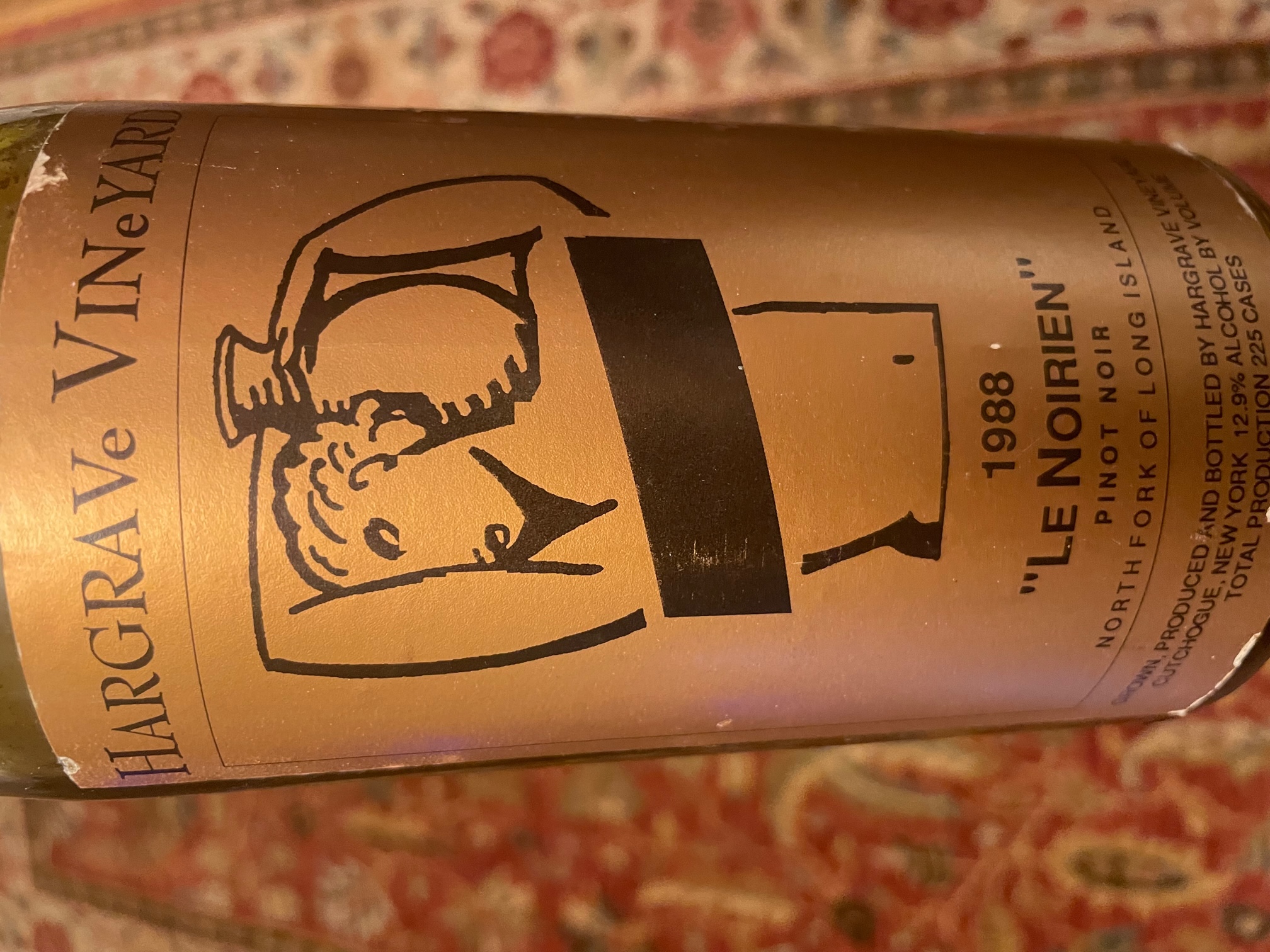

One bottle caught our eye: It was a 1988 “Le Noirien” Pinot Noir with a label unlike the others. It was gold, with a black line drawing of a nude woman, arms raised, balancing an amphora on one shoulder. There was a thick, black stripe across her breasts. Total production was 225 cases.

One bottle caught our eye: It was a 1988 “Le Noirien” Pinot Noir with a label unlike the others. It was gold, with a black line drawing of a nude woman, arms raised, balancing an amphora on one shoulder. There was a thick, black stripe across her breasts. Total production was 225 cases.

We bought two bottles. We opened one several years ago and it was impressive. But we could never open the second. Yes, we know we invented Open That Bottle Night for bottles such as this one. Still, it was just too special. It wasn’t the wine itself. It was that we remembered the girls playing on the beach of the Long Island Sound, Dottie steaming lobsters and fresh-picked corn and how we enjoyed that bounty as the sun set with a wine made nearby.

That 1988 wine surely was not built to last more than 30 years, we figured.

This bottle moved from our New York City apartment to our country cabin north of the city. When we sold our house earlier this year, it moved back to Manhattan with us. Just recently, John was organizing bottles in one of our wine coolers and saw it. For some reason, we don’t often take close looks at our older bottles -- they’re for “another night” -- but what he saw this time concerned him.

“It looks like motor oil,” he told Dottie, who, despite having zero experience with motor oil, figured that wasn’t a good thing in a wine bottle. “I think we need to open it to make space for another bottle,” John added. So we sat by the window the very next night to open the bottle and, we assumed, then pour it out and save the label.

We had two glasses ready just in case it was still drinkable.

When we studied the bottle more closely, it looked far better than John initially had thought. The fill was good and the wine looked fine. Maybe there had been an odd shadow.

The cork, at first, appeared sound. We used a prong opener and all was going well when, ooof, the top half came off. John got the crumbly rest with a small corkscrew.

We opened the bottle at 6:50 p.m., and, to our surprise, sweet, cedar-like Pinot Noir aromas leaped out. We were ready to taste immediately in case the wine was OK but might go right over a cliff. But we had to take a few beats to remark that the nose – with rose petals and more than a little barnyard -- reminded us of a visit to Beaune decades ago when we told a restaurateur that we were there to drink old Burgundies.

In French, he said he had just the thing but we needed to understand that the bottles did not have labels. Dottie answered, in what French she could muster, that would be fine. He went into his cellar brought up two bottles covered in dust and with vintages written on them in white chalk. The wines were ephemeral and tear-worthy, with the kind of complex layers of flavors and heady noses that stamp old Pinots on our hearts. (For more about that effect, check out the new book, “On Burgundy: From Maddening to Marvelous in 59 Wine Tales,” from the Academie Du Vin Library.)

We had not tasted the Hargrave yet and we’d already traveled to France.

We had not tasted the Hargrave yet and we’d already traveled to France.

We knew from the first sip that we were most certainly not going to be pouring it out. It was very good, a well-aged old Pinot – past its peak, but proudly mature, majestic even. We were amazed.

There was a time after about a half-hour when we thought it might be going downhill because it was silent, static. But, instead, it came back with some chocolate-covered cherries. This was quite a shock. It was still excellent and had not lost anything.

We then opened some creamy French feta – we had been concerned about doing that because the feta might overwhelm the wine, but we were hungry. The feta on crackers once again changed the wine. At 10:10, more than three hours after opening, it burst into licorice-cherry Swizzlers, rich leavening earth and sweet purple fruits.

Absolutely remarkable and surprising.

When we later spoke to Louisa Hargrave, after leaving her a message about how good the wine was 35 years later, she said, “I sent your message to Alex and my kids and they are so happy about it. We knew it was a great wine, but with Pinot Noir, ‘the Heartbreak Grape,’ you never know.”

They planted European varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, “but when we planted them, we didn’t know what they would be like here,” she said. In August, she was feted at the 50th Anniversary Grand Celebration of the founding of the Long Island wine region.

With the 1988 Pinot harvest, Louisa and Alex, now her ex-husband, knew they had something special. “The fruit was perfectly ripened, impeccable, and it tasted wonderful,” she said. They bought two costly large French oak barrels just for this wine, “a massive risk” because of the expense. And they wanted to do something very different with naming it and so looked up words describing the dark-skinned Pinot Noir grape and found “Noirien,” one of the names Burgundians used centuries ago for Pinot Noir, “the Black One,” she said. Because U.S. labeling rules prohibited the use of “nudity, children or religious symbols” on labels back then, the Hargraves used a “classic” female form and put a black strip across her breasts.

“Looking at it now,’ she said, “it’s a potent statement about censorship. It’s very provocative and it was our Hargrave protest move. We were in a new region doing things our own way and doing things people said we couldn’t, so we were going to do them anyway. And you can look at it and imagine whatever you want -- and you will, and it’s just wonderful.”

That’s magic. And magic is the best accompaniment on Thanksgiving. Happy holidays.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett