This column began innocently enough. John was just trying to buy some Beaujolais.

Fall makes us think of Beaujolais. While we’ve always said it’s a year-round wine – good at various serving temperatures and with all kinds of food – there’s something about pairing Beaujolais with fall that’s special. Partly it’s because we’re thinking of slightly heavier food. More deeply, fall is a time of simple pleasures, like watching the leaves change and, to us, Beaujolais is very much the same: real, with an elemental, natural feel.

John dropped into two mid-sized wine stores next to the supermarkets near our country cabin, where we have been sheltering for months. Neither had a Beaujolais of any kind, not a simple Beaujolais nor one of the cru Beaujolais from 10 special villages. So he went online to stores that could easily and inexpensively deliver to us. Once again, Beaujolais was harder to find than he remembered, and more expensive, too.

What is going on? So we contacted Inter Beaujolais, an association of winemakers, grape growers, cooperatives and merchants. It sent along its latest report, which included a candid introductory letter from the president of the organization, winemaker Dominque Piron, who wrote about “remotivating the troops” and needing to “rebuild an effective force of committed winemakers and négociants.” (The report is an excellent guide to Beaujolais, with interesting facts and overviews of the region and all 10 crus, which are generally higher in quality. The 10 are Brouilly, Chénas, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Juliénas, Régnié, Saint-Amour, Morgon and Moulin-à-Vent.)

What is going on? So we contacted Inter Beaujolais, an association of winemakers, grape growers, cooperatives and merchants. It sent along its latest report, which included a candid introductory letter from the president of the organization, winemaker Dominque Piron, who wrote about “remotivating the troops” and needing to “rebuild an effective force of committed winemakers and négociants.” (The report is an excellent guide to Beaujolais, with interesting facts and overviews of the region and all 10 crus, which are generally higher in quality. The 10 are Brouilly, Chénas, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Juliénas, Régnié, Saint-Amour, Morgon and Moulin-à-Vent.)

(Dominque Piron)

The report introduced the region’s new slogan: “Nouvelle Génération.”

At this point, it became clear that Beaujolais is working out some problems. How bad is it? We checked Google Trends for “Beaujolais” in the U.S. and, whoa, the chart looks like an EKG line of a patient on Grey's Anatomy. The line spikes every November, when Nouveau is released, and then quickly goes back down. But the most extraordinary thing is that the spike has gotten lower and lower and lower.

And it doesn’t look like the bleeding will stop soon. Karl Storchmann, executive director of the American Association of Wine Economists, sent along a chart showing that vineyard values in most areas of the Beaujolais region have flat-lined or even declined for 20 years. “For economists, land prices are an interesting research object as they look into the future and express people’s expectation, just like stock prices do,” he told us. “In general, factors like expected market declines or climatic changes are already factored in. Whether a part of the slumping Beaujolais prices is due to climate changes, as is the case in Southern France, remains to be analyzed. It may simply be a change in fashion as has been the case of Sauternes.”

So we contacted Piron, 70, whose ancestors began making wine in the region in 1590. He said Beaujolais suffered for a number of years.

“Thirty years ago, to be honest, things were running so well in Beaujolais that Beaujolais sort of withdrew in itself, closing the door to new people, with no vision for the future,” he said. “Slowly, financial difficulties arrived, the winegrowers’ children left to do another job, the wine merchants who were ‘Beaujolais specialists’ became more ‘generalist’ and so on.”

He said Beaujolais also was squeezed as consumers moved toward bolder red wines on one side and more whites and rosés on the other. This left Beaujolais’s charming Gamay-based “happy wines,” as he called them, in the middle. Beaujolais imports into the U.S. have risen somewhat since 2015, Inter Beaujolais reports, but Piron said sales seem poised to stall this year. And he said the immediate future is worrisome, too, “with the strong competition between wines in a weaker economy everywhere because of the pandemic.”

He said consumers have increasingly moved away from Nouveau and are slowly discovering the crus, which is where the industry thinks its future growth and profits will come. “In the past 3-4 years, we succeeded in improving the image of Beaujolais,” he wrote us. “Nouveau is not any longer the head of the train. The crus are taking the leadership and the Nouveau becomes again just an event in November – a nice event, we like it, but just an event.”

When we read that, it struck us that John hadn’t seen a single wine from Georges Duboeuf, either online or in stores. Duboeuf, who made Nouveau an international sensation, died earlier this year. In the past, we used to see his wines – not just Nouveau, but the crus as well – pretty much everywhere. We called Dennis Kreps, co-owner of Quintessential Wines, based in Napa, which has imported Duboeuf since 2016.

He said that while they still import about 150,000 cases of Duboeuf-branded wine – that figure was more than a million about 20 years ago – they’ve moved instead toward smaller producers that are grouped under the Duboeuf Domaines umbrella. There are more than 25 of them and they all import 10,000 cases or less -- and most just a few hundred cases -- mostly of cru Beaujolais. Duboeuf’s company “brings them together to market these brands internationally,” he told us. Most have had long relationships with Duboeuf. Duboeuf has purchased the entire production of Gérard Charvet’s Domaine des Rosiers Moulin-à-Vent since 1976, according to the Duboeuf Domaines’ site. Château des Capitans, which makes Juliénas, is owned by the Duboeuf family.

“They’re all unique personalities, they’re multi-generational, family-owned, really putting their passion into it,” Kreps said.

He said that selling Beaujolais has become much easier over the past few years as smaller producers like these have become ascendant. “Consumers are looking more toward a craft producer as opposed to a larger brand,” he said. “The younger, newer consumers are looking for small, eclectic producers, small estates, and those brands have done really, really well.”

Bottom line: Beaujolais is in a transition period – or, put another way, a dynamic period -- when the old guard is stepping back and younger, quality-oriented vintners with new ideas about making and selling wine are becoming more prominent.

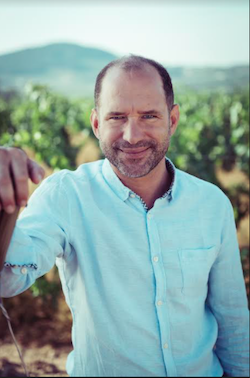

That’s what Piron says Nouvelle Génération is all about. And that is personified by Grégory Barbet, 45. His family has been making wine in the region for 300 years. He owns, with his sisters, Domaine de la Pirolette in Saint-Amour. He is head of Terroirs et Talents, a group of medium-sized family wineries in the region mostly run now by a younger generation.

That’s what Piron says Nouvelle Génération is all about. And that is personified by Grégory Barbet, 45. His family has been making wine in the region for 300 years. He owns, with his sisters, Domaine de la Pirolette in Saint-Amour. He is head of Terroirs et Talents, a group of medium-sized family wineries in the region mostly run now by a younger generation.

(Grégory Barbet)

“The older generation, the baby boomers, they lived in the golden age of Beaujolais in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s with the extension of worldwide Beaujolais Nouveau,” Barbet told us. “Duboeuf was very, very strong. At that time, people were looking for light, fruity, enjoyable wine. When your region is successful, you have no reason to change. In 2000, Beaujolais started to be in crisis and so now we have a new approach. It’s more eco-friendly. More estates are turning organic and also don’t want to produce the light, fruity style but want to produce wine with a little more character.”

He said a 10-year soil analysis of the entire region completed in 2017 has given the new generation a road map of how to produce wines of unique character from Beaujolais’s ancient and varied granite soils.

About the prices. The Inter Beaujolais report is quite up-front about it: “A positioning strategy has been designed and will be led over the next 10 years with a common goal: the gradual move upmarket for the Beaujolais range.” Piron told us: “We need to improve the prices because the cost to produce is high, a lot of work by hand, and winegrowers have to live decently, but we’ll certainly need a bit more time because of the pandemic.”

We asked Barbet if he thought it was feasible to raise prices. “It’s possible to raise prices reasonably if the wine is better,” he responded simply. He added that there should always be a place for “entry-level, simple, inexpensive, very drinkable party wine for the young crowd,” but there should also be room for mid-range and higher-priced Beaujolais. “We are starting to produce wine with true terroir, single-vineyard wines, in small quantity, very special, with longer aging to produce exceptional wine,” he said.

The 25% tariff levied by the U.S. certainly hasn’t helped. Michele Peters, an import portfolio manager at David Bowler Wine who handles several smaller Beaujolais producers, said that’s caused an average 10% to 15% increase in the price of her wines, with much of the additional pain split between the producer and the importer. “We wanted to share the burden,” she said. “I felt bad asking the producers for any sort of break because it’s our problem, it’s our government, but if they sell less wine it’s bad for them, too. That’s the only way I could ask in good conscience.”

She noted that another importer increased the cost of a bottle of Côte de Brouilly from $24 to $30 because of the tariffs. We’d guess that, for American consumers, that’s a significant leap for a Beaujolais.

We also tested our theory that Beaujolais is good with all kinds of food by having one with baked tilapia. It was excellent, with the earthiness of the wine playing off the sweet plumpness of the fish.

Shopping for Beaujolais can be challenging – except, of course, on the third Thursday of November, when Nouveau arrives and is a great excuse for a party that night. There’s some white Beaujolais, made from Chardonnay, and even rosé. But some stores have no Beaujolais and the better crus might not say “Beaujolais” on the label. The des Tours we had, for instance, identified itself as “Red Burgundy Wine,” which technically it is, but this wouldn’t help you know it’s a fine cru Beaujolais.

Even on some good wine web sites, if you search for “Beaujolais,” they will only show you wines that are actually labeled Beaujolais or Beaujolais-Village, generally a step up. If you wanted to find the cru Chiroubles, you would need to look for Chiroubles. And if you walk into many stores and specifically ask for a Chiroubles, well, good luck. The wines from 2019 are beginning to show up now and their freshness is always a plus, but the better wines from 2017 and 2018 should still be very good if kept well (as opposed to baking on a shelf in a bad store).

Still, with all of those caveats, we can’t urge you strongly enough to make Beaujolais a part of your regular wine repertoire. It’s generally delicious and, even with somewhat higher prices, a bargain. In the midst of very difficult times, it’s an easy-to-embrace treat. And all of that is why Dominique Piron remains optimistic.

“Every vineyard region in France, and in the world, has known high and low income levels,” he wrote. “Life is a cycle. In France, Beaujolais was certainly the first to fall into the hole; it’ll certainly be the first to get out of the hole….

“A new generation is arriving to grow vineyards, and even now, a few of the children who left are coming back. A new energy is here now….We have nobody to imitate or copy, we have just to exist for our real values.

“We believe in this region.”

So do we. And we wish it the best of luck. Beaujolais is one of the wine world’s natural wonders and, with a nouvelle génération, we believe it can indeed come out of this better than ever. As Grégory Barbet put it: “It’s very important that the U.S. consumer have a new image of our region. It’s tough sometimes, but it’s very exciting because we are writing a new page.”

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner art by Piers Parlett