Americans will drink an ocean of Sauvignon Blanc over the next couple of summer months. Tasty, inexpensive bottles are flooding in from all over the world, from New Zealand, from South Africa, even from Peru. We just had a Chilean Sauvignon Blanc from Veramonte that would be lovely by the pool on a hot day and is a bargain at about $10.

The only wrinkle here is that this abundance of affordable quaffers obscures the fact that Sauvignon Blanc is a noble grape that can be made into something far more interesting. It is, after all, one of the main grapes of white Bordeaux, including the astonishing sweet wine Château d’Yquem.

Merry Edwards, the famous California winemaker, is a passionate advocate for better Sauvignon Blanc and makes a barrel-fermented, lees-stirred Russian River stunner that costs about $42, and sometimes a late-harvest Sauvignon Blanc. “People tend to treat Sauvignon Blanc like it’s a simple picnic wine, but it is one of the two great white grapes of the world,” she said. She made her first in 1979. We called her 2016 “majestic.”

Cliff Lede Vineyards in Napa Valley makes one that includes 12 percent Sémillon (to add complexity and richness to the lean Sauvignon Blanc, they told us) and 2 percent Sauvignon Vert (to add “white peach character”). We said in our tasting notes for the 2017: “This is a very serious wine.” It costs about $25.

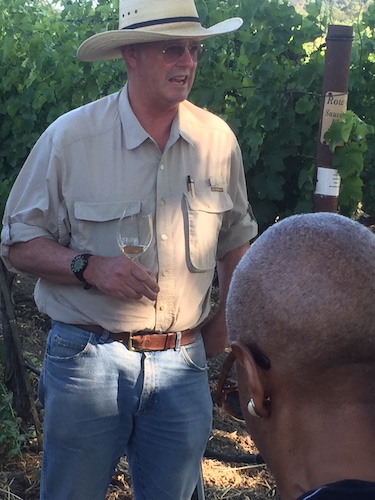

But, to us, the mother of Sauvignon Blanc is Sancerre, from the Loire Valley of France. How different is the Loire’s Sauvignon Blanc? Well, it’s so different that it persuaded California grape grower Tom Gamble to become a winemaker. As Gamble, of Gamble Family Vineyards in Napa, tells the story, he “hated” Sauvignon Blanc when he was younger. “Too green and acidic,” he told us recently.

Then the third-generation farmer visited the Loire in 1986. “They were more nuanced” there, he said. “It was a revelation to me that it could be a fine wine and, with some age on them, profound. I didn’t know I liked white wine back then.”

He decided if he were going to have a good Sauvignon Blanc from the U.S., he’d have to make it himself. Now Gamble makes two from four Loire and Bordeaux clones, with native yeast, oak fermentation and extended lees time. The regular one, $25, is lively, floral and minerally. The small-production unfiltered one, called Heart Block, which sells for $90 only at the winery and to club members, made Dottie swoon with its minerality and soulfulness. If you visit by appointment, you’re greeted with Heart Block, so named because the Gamble Vineyard in Yountville is located at the center of Napa Valley, Gamble told us.

Many Sauvignon Blanc wines come from the Loire – we’ve always been fond of Pouilly Fumé – but there’s something special about Sancerre. It has a confidence and depth that seem wise, even as it retains that lemon-lime, acidic, mineral-rich crispness that defines good Sauvignon Blanc.

What’s the difference between a nice Sauvignon Blanc and a really good one? Let Valentina Buoso explain.

“Nowadays, the wines are so technical, so purified. I’m exaggerating, but they’re made more by design, by people who have decided that they are trying to get the market with people who drink more rosé than reds,” Buoso, the winemaker of Domaine Pascal Jolivet in Sancerre, told us. “We don’t do technical wines. We don’t need to. The wine already expresses what is important. It’s the minerality that is speaking, some acidity that is speaking. When you taste, you taste the estate, the region, a particular part of France.”

Buoso, just 32 and from Venice, became head winemaker for the well-respected Domaine Jolivet in 2013. In Italy, she said, there’s still some difficulty for women who want to be winemakers. But who would guess that an Italian woman would have an easier go of it in France?

(Photo, right: Winemaker Valentina Buoso in the barrel room at Domaine Pascal Jolivet in Sancerre)

We called Buoso recently after tasting three head-banging Sancerres from 2017 that she made: Clos du Roy ($33); Les Caillottes, which is what the French call the exalted, small Kimmeridgian limestone rocks found in the Loire Valley, Burgundy and Champagne ($41); and Le Chêne Marchand ($46). Other winemakers source from these well-regarded vineyards as well.

The grapes Jolivet uses, organically grown in limestone-rich or chalky soils, are picked and sorted by hand. The juice is left on the lees for varying times and fermented with wild yeasts in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks.

Buoso spoke to us while on maternity leave; her first child, Flora -- “like flowers,” she said -- is almost five months old. Her husband, Alberto, is a winemaker at another winery. She admits to continuing to do winery work while on leave, explaining, “When we are passionate, we don’t feel the pressure.”

She credits much of her interest in wine to a teacher who took a wine course with her when she was 16. “He encouraged me. I started studying and the more I studied the more I liked it,” she said. She earned a bachelor’s degree in viticulture and oenology from a university in Italy, with a specialty in wild yeast, did post-graduate work at another Italian university and got a master’s from a joint program at the universities of Montpellier and Bordeaux. She also has worked at wineries in California, Oregon, New Zealand, Australia and Chile.

She loves working in the Loire Valley. “Year after year, I discover something else about the region or the potential that is in the soil. We talk a lot about terroir and climate and soil and there’s really a nice exchange this dynamic leaves in the bottle, in the wine,” she said. “We work quite naturally.”

To be sure, not all Sancerre is excellent. We’ve had some that simply seemed flat. So if you are going to spend $40 or so on one, we’d urge you to consult a good wine merchant. You might even want to take in our notes and say: “I want one that will taste like this!” Here they are:

Les Caillottes: “Ripe lime goodness. Long, tangy finish. Mouthfeel, too, lees. Richness, a little oily – nicely oily, like the peel of a lime. Great acidity, flinty, minerals. It’s clean and crisp with a juicy ‘drink more of me’ kind of SB thing. The finish makes this even more interesting. This has an end so there are all the segments – beginning, middle and end, and they all taste a little different. It’s crisp and focused, with a touch of lusciousness on the finish, only on the finish. This would make any dinner special, a white tablecloth kind of wine. It’s elegant. It’s got stuff.”

Buoso said Les Caillottes is “one of my favorite wines. It represents very well the domaine. It has everything.”

The Clos du Roy, we wrote, was “focused and pure, with lemon-like flavors. Better with air, though less intense than Les Caillottes. Lychee, white fruits. River stones.”

Buoso said of the two vineyards, “They’re very close to each other, but the exposure is different. There’s a lot of minerality with the du Roy, more limestone than chalk. More white flowers, much more body than the Les Caillottes.”

We did not find our first sips of Le Chêne Marchand impressive, though Dottie liked it better than John, who wrote, “Nicely bitter lemon peel, minerals and stones. Long, tangy finish but not as focused as I’d like.” With air and warmth, though, Dottie fell hard for it and wrote, “Tasting later, this is the total package, classic. It’s crisp, with lime peel. Also with some length that ends in seashells and depth. Nice walnut bitterness. Everything you’d want in a Sancerre.”

The next day, after retasting what was left in the bottle, John told Dottie, “You were right.” Let’s repeat that--Dottie writing this—John said, “You were right.”

These are best served closer to cellar temperature (55 or so) than refrigerator temperature. And one more thing: Several times as we tasted the wines, Dottie said, “I think we should decant these.” She felt they were so interesting, with so many layers, that they would stretch even further given more air. John resisted.

When Dottie interviewed Buoso, she asked about that. Buoso laughed. “Yes,” she said. “Absolutely, I decant. I encourage people to decant. The wines are dense and rich and they need some oxygen.”

So there.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective

Read Lisa Denning's Grape Collective interview with Pascal Jolivet