MFEO isn’t an acronym we toss around lightly. To be perfectly honest, we’d never even heard of MFEO until we watched one of Dottie’s all-time favorite movies, “Sleepless in Seattle,” which was, to his ever-lasting regret, brought to her attention by John. She could watch it every night. The right people end up together because they were: Made For Each Other.

Jill Klein Matthiasson and Steve Matthiasson, of Matthiasson Wines in Napa, were MFEO. She grew up in Pittsburgh and he grew up in Tuscon and both from a pretty early age felt their calling was in farming, and only a little later, about farming grapes. Matthiasson Wines makes restrained, beautifully balanced, elegant wines not only from the usual grapes like Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon but from “others,” like Ribolla Gialla and Tocai Friulano and Schioppettino. The circularity of their lives is some sort of magic, what everyone yearns for in their Valentine. They got married in 1996, a year after they made their first wine, and have two adult kids, Harry, 26, and Kai, 23, who had just made a batch of butter the morning we spoke to his parents.

Jill, 61, had to get past Steve’s “funny-looking beard,” she confided when we called them recently. “At first, I didn’t think much of him.”

Jill, 61, had to get past Steve’s “funny-looking beard,” she confided when we called them recently. “At first, I didn’t think much of him.”

“Immediately it was like I want to date her,” Steve, 54, told us.

(Steve and Jill tasting wines and blends at their estate vineyard)

Well, we asked, how long did it take for you to ask her out?

“Here’s the thing,” he said, pausing. “I was nervous about asking her out and so it took me, it probably took me an inordinate amount of time and my roommate basically had to do an intervention. He said, ‘Dude, if you don’t ask her out I’m going to.’”

The notion that farming might be her life’s work occurred to Jill while she was studying botany at the University of Pennsylvania. She also studied for two years in Israel harvesting rainwater and learning other types of early farming methods. She worked in Tucson at a nonprofit founded with the help of Gary Paul Nabhan, an agrarian activist who helped start the eating local food movement as well as the heirloom seed-saving movement. Among the books he’s written is “Jesus for Farmers and Fishers: Justice for All Those Marginalized by Our Food System.” At UC-Davis for graduate school, Jill studied soil health, sustainable agriculture.

“Truth is that I just got this idea in my head that I was interested in farming. No real reason except that I was a dedicated environmentalist and people make environmental choices every day by eating and therefore organic farming seemed like a good way to promote environmentalism,” she said.

“Recently I’ve been doing some genealogy research and have discovered that my paternal great-grandparents were farmers in the old country on one side and tavern owners on the other side, so growing grapes and making wines seems to be more in my DNA than anyone thought,” she added.

Steve was on sort of a parallel route. Although he was born in Winnipeg to anthropology professors, his family had a farm in North Dakota. When he was 7 and his parents were divorcing, he spent a serene, indelible summer on a cousin’s farm in Manitoba, where he fell in love with farming. He moved with his mother to Tucson and attended a school where students cared for farm animals and plants. A group of global environmental activists who visited the school also had a deep effect on him. In an article about the pair by Tim Carl in which Steve mentions the activist environmentalist Edward Abbey, Carl notes, “In another of his popular books, ‘A Voice Crying in the Wilderness,’ Abbey wrote: ‘How to Overthrow the System: brew your own beer; kick in your Tee Vee; kill your own beef; build your own cabin…’ a sentiment that captured much of what would become Steve’s future.”

Indeed it has, and Jill’s too. They call themselves extreme environmentalists. After studying philosophy in college, Steve moved to San Francisco in the early 1990s and supported himself as a bike messenger, brewed his own beer, and found a way to nourish his love of growing things and the environment. “I got involved with the San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners. It isn’t around anymore but it ran all of the community garden plots. I had my garden plot, and I was very passionate about my garden plot. I did that for three years, but I was stymied” in search of a way to farm organically in a larger way, he told us. He took a leap and got into UC-Davis’s horticulture program and landed an internship helping orchards in San Joaquin Valley develop sustainable ways to grow their fruit.

Jill had gotten a job with a farmers’ nonprofit and met Steve when he had that funny-looking beard. She was a friend of his roommate. The nonprofit was Community Alliance With Family Farmers and that’s where she started a farmer-to-farmer information-sharing network. “Farmers learn the most from other farmers. They trust the information they get most from other farmers, farmers who have experience either farming organically or using reduced pesticides,” she said.

About six months later, when the nonprofit got an EPA grant to work on reducing pesticide use with a consulting company that helped growers of almonds and also grapes, she hired an intern, Steve. He was a first-year graduate student in horticulture and pest management at UC-Davis. That was in 1994.

His job? To count earthworms. “And other things,” he quickly added. An abundance of earthworms is a good indicator of soil health. Soil treated without pesticides has more earthworms than soil treated with pesticides, for example.

Working with farmers, he decided it was a good idea to shave that “funny-looking beard” and Jill said yes when Steve finally got around to asking her out. Their first official date was a Jackson Browne concert to which a friend accompanied them. They hit it off so well that they dropped the friend off and the two of them went to dinner. “We had our first kiss after that dinner,” Jill said.

Soon after, they decided to make their first wine together. A UC-Davis student, he had the map of the student vineyard. “Nobody liked Muscat so we were going to make a Muscat of Hamburg wine,” he said. “It was our first vintage, the first wine we made together, 1995,” she said. “We were into local food and that whole world and it was all new and exciting in the ’90s. Alice Waters was doing her thing. So we went into the school vineyard and we wanted to make wine out of something really cool and interesting and different and we loved this particular grape. You probably know it. Quady made one, it’s Black Muscat,” Steve said.

Soon after, they decided to make their first wine together. A UC-Davis student, he had the map of the student vineyard. “Nobody liked Muscat so we were going to make a Muscat of Hamburg wine,” he said. “It was our first vintage, the first wine we made together, 1995,” she said. “We were into local food and that whole world and it was all new and exciting in the ’90s. Alice Waters was doing her thing. So we went into the school vineyard and we wanted to make wine out of something really cool and interesting and different and we loved this particular grape. You probably know it. Quady made one, it’s Black Muscat,” Steve said.

(Dottie with Matthiasson Chardonnay at Wine Writers Symposium at Meadowood, Napa)

How did it turn out? We asked.

“It turned out great,” he told us. “And it was a great lesson in winemaking because it didn’t turn out the way we expected. I had neglected it because I spent all of my time going over to Jill’s house and eventually moved in with her and then I remembered. The wine! Oh man, I’ve got to deal with this wine. So I was dumping it out and said, ‘Oh, that smells good. It had turned to sherry. It had flor yeast on top of it. So I saved it and we bottled it and we had it for years. It was a fun thing to learn about wine: It doesn’t necessarily go the way you expect it. You have to honor the process, the direction that the wine takes.”

He is a firm believer that wines are made in the vineyard and they cherish the opportunity to nurture the land and the people who work on it. The couple are active supporters of the 280 Project, based in San Francisco, which exposes minorities to the wine industry, from vine to bottle, so that they might decide to get jobs in it. Matthiasson Wines is certified organic and “fiercely independent,” but they balk at the term “certified sustainable.” “You can be on the path to sustainability but not certified sustainable. We, as an agricultural community, are not there yet. We need more innovation to achieve sustainability. We still haven’t solved the housing issue for farm workers,” he said, for example.

Jill used her position at Community Alliance With Family Farmers to work with organic farmers throughout California, people growing walnuts, peaches and vegetables. “I got to know a lot of organic farmers like that and I did it for 10 years,” she told us. Among other things, Jill taught them how to sell directly to consumers using a model called Community Supported Agriculture, where consumers buy shares of a harvest in advance, sort of like wine futures.

In 1996, Steve helped write what’s known as the Lodi Rules for Sustainable Winegrowing, a groundbreaking set of guidelines so influential that its model spread. Working in Lodi was the first time Steve had worked exclusively with grapes, and from there, he worked as director of Viticulture Research for R.H. Phillips winery. He became a much sought-after consultant on conscientious grape growing and today also teaches organic farming at UC-Davis.

After Steve was recruited to help start Premiere Viticultural Services, a vineyard management and consulting business in Napa, the couple moved to Napa in 2002 and founded Matthiasson Wines in the West Oak Knoll region in 2003. “We wanted a small, family business [wine and farming] that Jill could focus on,” Steve said. In 2014, the San Francisco Chronicle named Steve its Winemaker of the Year and in 2012, Food & Wine named him one of its winemakers of the year.

They started with 120 cases and now make 12,000 cases including a charming Chardonnay from the famed Linda Vista Vineyard that we just tasted at the Wine Writers Symposium at Meadowood Napa Valley, hosted by Meadowood and the Napa Valley Vintners.

The move to Napa to make wine did not halt their passion for growing other things to eat. “We hadn’t lost track of our idealistic dream of growing food,” Steve told us. Part of a vineyard property he was working on was unsuitable for grape growing, he said. “I was telling Jill about it and she said, why don’t you see if they’ll let us grow fruit trees there. That was our chance to grow some food in the Napa Valley,” he said.

The move to Napa to make wine did not halt their passion for growing other things to eat. “We hadn’t lost track of our idealistic dream of growing food,” Steve told us. Part of a vineyard property he was working on was unsuitable for grape growing, he said. “I was telling Jill about it and she said, why don’t you see if they’ll let us grow fruit trees there. That was our chance to grow some food in the Napa Valley,” he said.

(The Matthiassons selling their produce years ago at Napa Farmers Market)

What do you grow and where? We asked. “Peaches, plums, nectarines, figs, apples. It’s a mile or something like that from our house. When we moved here, people were bringing in their fruit and vegetables from outside Napa to sell at the Napa Farmers Market,” Jill said. Some Napa residents told them it was impossible to grow peaches there, she added.

Their bounty makes Valentine’s Day sometimes a conundrum, Steve told us.

“Going out to dinner for us, it’s always bittersweet in a certain way because we grow our own vegetables. We have a giant garden with amazing produce so we like to cook ourselves. But then we have restaurants that support us and our wines and are happy to see us. We’re friends with the owners, but we actually rarely go to restaurants. We do a lot of stuff from scratch. That’s what we enjoy. It’s a way of life.”

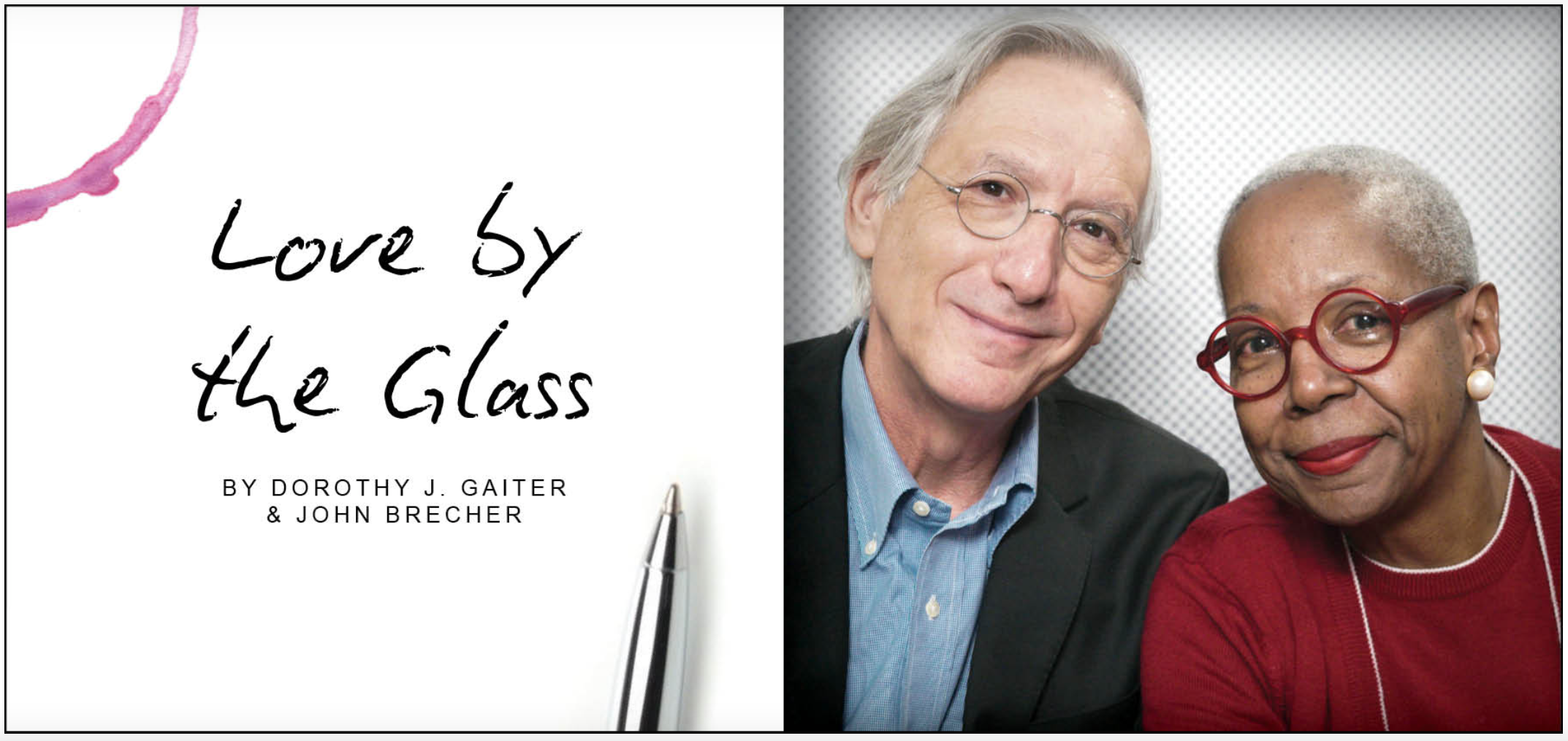

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett