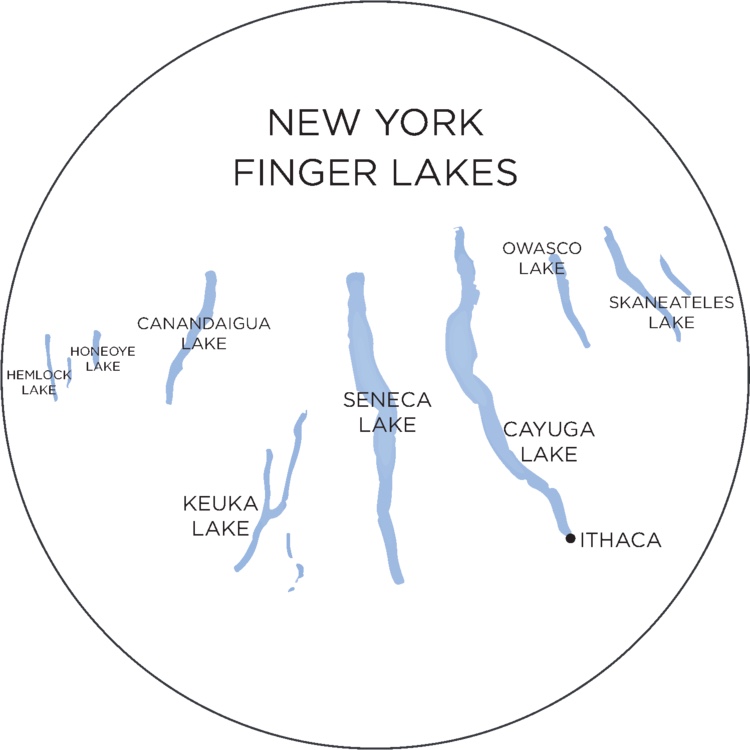

Thomas Pastuszak, Wine Director of The NoMad Restaurant, was pre-med at Cornell University when he fell in love with the local Finger Lakes wine. Little did he know that this new love would alter the course of his life. After college, he headed back to his hometown of New York City and decided to forgo medicine to pursue a career in the restaurant business. In 2014, with a dream of making a Finger Lakes dry Riesling, Thomas started his own wine label, Empire Estate. The fruit is sourced from several growers and the wine is made in collaboration with winemaker Kelby Russell at Red Newt Winery on the east side of Seneca Lake.

Grape Collective caught up with Thomas to talk about life as both a sommelier and a winemaker and whether having a fabulous head of hair helps to sell wine.

Lisa Denning: Can you tell us about your personal journey that led you to winemaking?

Thomas Pastuszak: I grew up in New York City and was always fascinated by science and music. I was a classical pianist and I really got into biology and ended up going to school upstate in the Finger Lakes for neurobiology. I was pre-med at Cornell University, but all my life I had worked in restaurants, whether it was as a toast boy at my godfather's bed and breakfast out on Shelter Island or bartending, serving and eventually managing restaurants when I made my move upstate. While there, I fell in love with food and wine, fell in love with restaurants, even more so than before, and at some point just decided to go full on into the world of restaurants.

When I lived in the Finger Lakes, I was focusing on restaurants in the area and I was learning everything I could about the world of wine. The wines of Chablis, of Bordeaux, of Barolo, they were of equal importance as the wines of the Finger Lakes because the Finger Lakes was my backyard. I was a 2-minute drive from the very best vineyards in the area. That took on a very significant weight for me. Eventually I moved back down to New York City with the intention of wanting to really focus on restaurants. There were some great opportunities that came my way, but I realized that not a lot of people knew about the very best examples of Finger Lakes wine. I made it a personal mission to showcase those wines, to feature them. I poured my friend's wines by the glass. I put together wine lists that showed as much breadth and depth in areas famous for Riesling for instance, such as the Mosel or the Wachau in Austria, and then I would have just on the next page, a section just as dedicated to Finger Lakes Riesling.

Eventually I wanted to start my own production. I wanted to create something from scratch. With having fallen in love with the Finger Lakes area, I wanted to start a production there and bring my love of Austrian and German dry Rieslings, and put that into an embodiment, which would eventually become Empire Estate.

What year did you start Empire Estate?

2014 was our first vintage. It took a little bit of time to get there, but there's a lot of inspiration and focus that goes into what ends up being just one bottle and the focus is Finger Lakes dry Riesling. We launched the wine project with the specific intent that there's not enough people drinking Finger Lakes wine and there's not enough people drinking dry Riesling. Riesling as a varietal has planted itself as the flagship varietal for the Finger Lakes in terms of white wine. I love dry Riesling, especially from Austria and from Germany. The style of the wine is very much influenced by that, but we also wanted to be able to make a wine that ideally we can get out to a number of different markets that don't see Finger Lakes wines. The intention is to get people to try the wine and ideally like what's in the bottle, fingers crossed! We really hope that we target and focus on people that don't already know the wines of the area.

Tell us how your wine is made?

For Empire Estate, in the first vintage in 2014, we started with just three vineyards that we worked with. We don't own our own winery and we don't own a single vineyard of our own, so what we were able to do is find a few growers with whom I was friendly when I was still living in the Finger Lakes. Also, we found a few growers with whom we made connections through our winemaker and the winery where we're making the wine. We established these very healthy contracts where we are able to work with specific parcels from their vineyards, and help to manage them as though they're our own domains. We've grown from three small vineyards to twelve different vineyard sites in the three years since we started production.

We're trying to focus on sustainability, really maintaining low yields in the vineyards to make sure that the quality of the fruit is very high. Also, just making sure that our farmers, our growers are well taken care of year after year. We make the wines at the Red Newt Winery, which is a fantastic winery in the region to begin with. The winemaker there, Kelby Russell, is a good friend of mine for many years. He and I are able to collaborate on the style of the winemaking. It is very much focused on what you would find in central Europe – Austrian and German techniques, in terms of the winemaking. That's everything from how the fruit is being managed in the vineyard to when it's brought in and how it's being treated. For instance, we love to implement skin contact with riesling, which means crushing the grapes, keeping the skins, and the juice in contact for a day, sometimes two days, and really engaging the skin and juice relationship. The style with which we ferment, which is often using yeast that we source from Austria and Germany, or performing native yeast fermentations. These are much more inspired by the techniques that you would see in central Europe.

There are a lot of varietals that are planted in the area. In terms of red wines, there's a lot of Bordeaux varietals that are planted because in the early 80s and going into the 90s, there was a lot of inspiration from the West Coast and from Bordeaux in terms of what types of varietals were to be planted. There's quite a bit of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot. Cabernet Franc for red wines is, I think, the varietal for the area. There's no other region in the US that's staked claim with Cabernet Franc, for instance, as the way that Napa Valley has with Cabernet Sauvignon. Cabernet Franc performs extremely well in cool climate regions — think the Loire Valley in France. There's a lot of similarities between the Finger Lakes and the Loire Valley. Not to mention that Cabernet Franc does very well in slightly cooler conditions like we have during our winter period. I think Cabernet Franc as a red varietal is super exciting and I think it's very cool that there's no other area that's really owned it. That said, there's also beautiful Chardonnay that people are making into sparkling wine, as well as table wine. You also see folks who are experimenting with northern Italian varietals, like Teroldego and Lagrein. You're seeing an explosion of rosé production in the area as well, from some of those Bordeaux varietals I mentioned before, and certainly from the varietals that you'll see, like Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir. There's a lot of experimentation, as well as a focus on the tried and true varietals of Riesling and Cabernet Franc.

One of the challenges of grape growing in the Finger Lakes can be the extreme cold. Have you noticed with global warming that it's actually a good thing for winemaking in the Finger Lakes?

It's a very challenging question because some people will say global warming, some people will say climate change. There's definitely something happening, but I think what we've seen is that there are more erratic weather incidents. We're talking about hails during the summer, cool spells in the late summer, extended fall seasons, and probably the most intense is when you see a January or February day where it gets a little bit colder than it used to get. You'll have certain varieties, certain vines that just don't fare as well when they're exposed to those really, really cold conditions. You'll have vine death because trunks will literally snap and the vines will die as a result of hitting those extreme temperatures, which is in part why a varietal like Riesling or Cabernet Franc can do well in those conditions because they're a little bit more cold hearty than a lot of other varietals that are planted in the area.

And your wine, how has it been received around the country?

It's interesting because New York City especially has seen Finger Lakes wines for a couple of decades now. You'll see some of the smaller producers making their way down here too because it's not too far of a commute to hand sell, or if you're not distributing, to get the wines here. The reputation and the quality of the wines have been going up. New York City is better than ever in terms of being able to find Finger Lakes wines. You still go to places like Boston, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles that have very little understanding of what Finger Lakes wines are about. Many people are already looking for this model of leaner, cooler climate, fresher wines to pair at the table, and the Finger Lakes has that. It's a great opportunity to be able to expose these wines, not just Empire Estate, but our friends' wines too to those other markets, and it's a breath of fresh air for most people.

On top of that, people just don't know what's happening in the area, so it's fun to be able to get to those cities and focus on the sommelier community and focus on the buyers who really care about what's happening in the soil, as well as what's happening in the cellar, and help tell the story of the region by doing that.

The Finger Lakes is a challenging place to make wine organically. What is your opinion of that?

I think that's a very true statement. It is challenging to practice organics in the Finger Lakes. It's a very humid region so you'll often see very rigorous soils that retain a lot of moisture. There's a lot of different types of disease pressure throughout the course of the year. I'm not just talking about pests and bugs, but frost, hail, and humidity that can often apply disease and rot pressure to the vines. It is indeed very challenging to farm organically. When you look at some of the places that are able to do it best, they're often regions that are drier, that have excellent airflow. They are places where you won't have as many of those pressures that I just mentioned. I'm in full support of those who are able to do it but there are only specific sites in the area where you can do that. Certain vineyards allow for organic viticulture more so than others where you need to use more conventional methods for farming.

Let's talk about the restaurant business. Nine out of ten restaurants in New York City don't make it past the first year. What is it about the NoMad restaurant and EMP (Eleven Madison Park) Group that makes them so successful do you think?

When the NoMad was opened in the spring of 2012, I was brought on as the Wine Director for the restaurant and it was a very ambitious opening because you have the team behind Eleven Madison Park, Chef Daniel Humm and Will Guidara, in terms of operations, basically running the show. The NoMad was supposed to be this very unique concept because we are a very high end hotel, but it's boutique, it's relatively small. At the same time, the NoMad restaurant concept would be running food and beverage operations for the entire property. The vision with the NoMad was not only should it be a great new vision of what a grand European hotel would be for the modern day traveler, but you would also have a fantastic restaurant for the modern day diner. We had this remarkable opportunity to create many different spaces and many cultures within the restaurant. We have a grand plush dining room, we have an open air atrium for one of our dining rooms. We have a grand barroom. We would have our library lounge, etc. We would have many different spaces for different people's needs. I think through the combination of the collective efforts of everyone on the team and the fact that we were creating a new niche, we were creating a brand new concept, not just a stand alone restaurant, but many different concepts within one building, I think that really set us apart when we opened.

Tell us about a typical day for you at the restaurant.

Today it's less typical than ever before because of the fact that we have a few more balls that are being juggled, but if I'm not visiting a restaurant trying to promote Empire State, trying to get people to taste the wine throughout the day, then I would typically get in to the restaurant sometime in the mid-morning when we have the administrative work to be taken care of during the day. Often there's meetings for events that we have happening in the restaurant. We often plan a lot of large scale events, such as the NoMad Masquerade, which is a big undertaking. I will take tastings with reps who are trying to get me to buy wine for the restaurant's wine program. I also go to auction to purchase wines from fine and rare collections for the restaurant. We have wine tastings that we host, some that are just with myself and the sommeliers. Once a week, we'll get together and I let the sommeliers pick wine from our cellar within a reasonable price point so then we can all do a blind tasting and keep our tools very, very sharp.

Likewise, myself and the sommeliers as a team, we host tastings and seminars for the entire restaurant staff. We really try to encourage the individual sommeliers to get passionate about a particular region, maybe they have it already. Maybe it's about an area that they're less knowledgeable on, but they want to become more knowledgeable on, and we host classes and tastings for the rest of the team. Any number of those things are happening usually before about four o'clock, which is when family meal happens and the entire team comes together to eat as a family. We get all of our service notes ready so we can line up at five o'clock and open up the restaurant at 5:30, and then from there, the curtains open and the show is going.

You must get a lot of reps contacting you who want to show you their wine. How do you decide which wines you'll taste?

Especially in New York, we're blessed with the sheer number of distributors that are out there. I find that it's very much about relationships, and of course you want to find the very best wines to suit your program, and so you have to have a specific vision of the type of wine you want to have in your wine program. At the same time, you also realize that it's about the relationships that you have with people. If you were to have three dozen different distributors with whom you're doing business, it's very different than if you chose 15 to 20 or even less. You want to make sure that you are taking care of your distributor and the reps who are taking care of you to make sure that everyone's happy.

At any high end restaurant, there's always this balance between what will be the star, the wines or the food. How do you deal with that challenge at the NoMad?

What's remarkable about our restaurant group, Make It Nice Hospitality, is that it's based on the idea that the dining room is not more important than the kitchen, the kitchen is not more important than the dining room. It's about a relationship and understanding that both parts need to be in beautiful synchronicity in order for the whole thing to work. That is very much imbued in everyone's perspectives, which is really, really important for relationships and for that balance. The approach when it comes to wine is it's a balance of building the wine list and the cellar that you want to have because you know you'll have a certain clientele. You'll have certain guests who want to enjoy certain types of wines. Basically finding those that will work well for their needs, but also building a wine list that really supports the cuisine.

What's remarkable about our restaurant group, Make It Nice Hospitality, is that it's based on the idea that the dining room is not more important than the kitchen, the kitchen is not more important than the dining room. It's about a relationship and understanding that both parts need to be in beautiful synchronicity in order for the whole thing to work. That is very much imbued in everyone's perspectives, which is really, really important for relationships and for that balance. The approach when it comes to wine is it's a balance of building the wine list and the cellar that you want to have because you know you'll have a certain clientele. You'll have certain guests who want to enjoy certain types of wines. Basically finding those that will work well for their needs, but also building a wine list that really supports the cuisine.

For instance, Chef Humm and the entire kitchen team at the NoMad have menu items with a lot of focus on acid-driven dishes and fresh seasonal dishes. It's very important that, for the wine program, I select wines that will pair well with those dishes. Fortunately what it often means is going to regions that are cooler climate, which typically means bright acidities with fresher characteristics in the wines that will pair well with the cuisine just based on the sheer nature of those wines. We're talking Champagne, Chablis, the Northern Rhone, Burgundy, Northern Italy. In the US, central coast California and the Finger Lakes.

Would you say your wine list represents several different regions around the world, even the obscure places?

It's heavily weighted on classics — Champagne, Burgundy, Bordeaux, Northern Italy — because these are regions that make remarkable wine not only for the cuisine, but they're very ageable wines coming from those areas. We can build verticals, we can have young wines and old wines. There's a great history to that area, but we also recognize that there's always new up and coming regions. We have sections like our Nomadic whites and our Nomadic reds, where we feature varietals or regions from less common areas, and it's a chance for us to be able to show off those lesser known regions and expose guests to something new.

How has your wine list evolved over the years that you've been there? Has it changed?

I would say the core ethos has remained the same because there's a vision and we're pushing for that. I would say that what we've been able to do over time is build our cellar and build our inventory. When we first opened the restaurant we had about 300 selections and now, we're close to 2,000 selections. That's largely based on finding one very special rare bottle that might be a little bit more expensive, but you can add it to that category of Burgundy or Rhone or Piedmont, for instance.

How important do you think wine education courses are for someone who wants to be a sommelier?

I think that people who pursue the path of becoming a sommelier have to recognize that you're working in a wine capacity and a restaurant. The greatest thing that you can do is better yourself, which means finding the best people that you can possibly work with, finding the best restaurants to work at, finding peers with whom you can share knowledge and share tastings, whether it's within the restaurant capacity or outside of the restaurant, and build your knowledge based on the fact that you'll learn more from tasting than from just reading a book. That said, you need the studies as well, and there's so many different ways to get that. I often find that it's to each their own, but today you have many different organizations that provide education. My personal recommendation is getting great restaurant experience in a place where they really invest not only dollars, but time into their education and combining that with programs that are external, that can really supplement the education that you're getting in the restaurant.

You oversee the making of some wines that are exclusively sold at the Make It Nice Hospitality restaurants. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Sure. We're in New York City and we have this amazing viticultural area right in our backyard, and that's the Finger Lakes, just a couple hours northwest. When we opened the NoMad, we had conversations about trying to create some wine that was specifically for the NoMad, and also for our sister restaurant, Eleven Madison Park. We're really close friends with the entire team at Hermann J. Wiemer Vineyard up in the Finger Lakes on the west side of Seneca Lake and we got together at the very beginning and said, "What can we do together?" We came up with producing some limited production wines where we can actually get our staff involved in the winemaking, in the winery itself. That means going out to help with harvest. That means tasting through wines that are being made and on their way to being a finished wine, which means going up and educating themselves in viticulture and winemaking as well and getting our staff involved in the process.

We forged this wonderful collaboration with Wiemer, and we created a special red for Eleven Madison Park. It's called Bye Bye Blackbird and it's a Cabernet Franc. Then for the NoMad, we created a very special sparkling wine, which is called Back to Zero, which is a brut nature blanc de blanc. We produce very small quantities of these two wines. They're very significant to each respective restaurant, and the only place that you can have them is either at the restaurants or back up at the vineyard.

Many consumers hear the word "Riesling" and they just automatically think it's sweet. How do you deal with that?

I actually love it as a challenge because I guess I'm always going after the underdog. I think that Riesling is misunderstood and some of the most beautiful examples in the world are off-dry or sweet examples. I also think that dry Riesling as a category is remarkable. One of the things that I get to do is to have guests put their trust in me and they want to be shown an experience. They want to have a new discovery, they want to be told a story. Oftentimes, I'll have a guest who comes in and says, "I just want to have a glass of dry wine. Something not too expensive." Maybe they won't pay it any attention, I'll come over and pour a dry Austrian Riesling or something from the Finger Lakes in a drier style, like Empire Estate. They'll taste it and they'll say something in the range of, "That's really good. What is it?" Then when I tell them that it's Riesling, a light has been shown, the doors are open, and they realize that Riesling can be made in a dry style. I think it's a misconception and often you just need to get the wine into people's glasses. You need to get them to taste it to realize what it can be. I know Chardonnay drinkers who end up loving dry Riesling, but they need to give it a chance first.

In the framework of putting a restaurant list together, what do you think about the new, leaner California style versus the big, blockbuster style?

The world over, there's many different styles of wine being made. There's also many different tastes that folks have. I personally have always been drawn to lower alcohol, leaner, less extracted wines. We're talking slightly more traditional producers. Today, you have a new wave of producers that are often billed as the 'New California', who are making wine in that more traditional old school, fresher style. I find that, especially in the context of building a wine list and pairing these wines with food, it's often easier to do that with wines that are constructed with more acidity, more freshness, less alcohol. They're wines that reinvigorate, that refresh the palate, and pair beautifully with cuisine. Again, you have to think about the food and what wine is going to go really well with that. In the end, those fresher, brighter, more lively examples are the ones that always pair better with the food and also will keep people feeling more alert and more alive throughout the course of their meal.

Speaking of the food, I think the roast chicken at the NoMad is the best in New York City. Which wines do you typically pair with that dish?

Thank you and I agree. The roast chicken has become very famous and we love it. Foie gras, black truffle, and brioche are blended into this wonderful stuffing that's put in between the skin and the meat of the breast. The bird's roasted whole, and then we carve the breast and it's served on its own, and we take the dark meat from the legs and it's fricasseed. Depending on the season, we change what's called the set — the accompaniments that go with it. If it's springtime, we're focusing on spring vegetables and flavors that are very alive and are happening during the springtime. In summer, you'll see more of the use of, for instance, corn because it's very much a summer vegetable. As we go into fall and winter, you'll see more root vegetables being used and darker flavors.

Thank you and I agree. The roast chicken has become very famous and we love it. Foie gras, black truffle, and brioche are blended into this wonderful stuffing that's put in between the skin and the meat of the breast. The bird's roasted whole, and then we carve the breast and it's served on its own, and we take the dark meat from the legs and it's fricasseed. Depending on the season, we change what's called the set — the accompaniments that go with it. If it's springtime, we're focusing on spring vegetables and flavors that are very alive and are happening during the springtime. In summer, you'll see more of the use of, for instance, corn because it's very much a summer vegetable. As we go into fall and winter, you'll see more root vegetables being used and darker flavors.

Honestly, depending on the season, that is how I choose which wines will pair best with that dish. Case in point, in the summertime, a rich white like a Rioja blanco from Lopez de Heredia, one of my favorite Spanish producers. It's a slightly oxidated wine and it's got some nutty, earthy tones to it. It's rich, it's robust. It can stand up to the black truffle, the foie gras, the brioche, but also pairs really nicely with some of the summer vegetable components. When we're talking fall and winter and we're looking at root vegetables, brussel sprouts, we're using certain meats in the fricassee as well. For instance, you'll see some chorizo in there or some other sausage meats that are blended in. We want richer, darker flavors. Then I look to northern Rhone Syrah, I look to Piedmont for great Barolo and Barbaresco. I would look to old Burgundy. Then, fortunately, we're able to balance that not only on the wine list in terms of bottles, but we have a pretty extensive by the glass program with over 50 selections. We're able to have a lot of diversity in terms of what people can be offered there.

Is there anything else you want to tell us about the restaurant?

For those folks who live in Los Angeles, we're opening up a NoMad in LA very soon. We're very excited to be able to have an outpost there. We have one coming up in Las Vegas as well, which is going to be as small and boutique and focused as the example that you have here in New York and in Los Angeles. We're really excited to be able to get NoMad out to other markets and get people to come under our roof and have some fun.

I have one last question. Recently there was an article on Grape Collective by Stuart Pigott, and it mentions you in the context of what "awesome hair can do for 'Fancy Wine.'" I'm wondering if we could have a few locks of your hair to put on display with the Empire Estate dry Riesling that we're selling at Grape Collective.

Absolutely. If it helps the cause and helps to sell the wine, I'll gladly do that.

You do have awesome hair.

Thank you, I appreciate it. It definitely helps with wine sales.

Read more from Lisa Denning on Grape Collective and on The Wine Chef.