Back in 2000, we wrote a column about wine and headaches that explored some of the theories about what actually causes these headaches. We started that “Tastings” column in the Wall Street Journal this way:

“Let’s talk headaches and wine. No, not hangovers. If you drink too much and you’re like most people, you will get a headache. And we’re not talking about migraines or cluster headaches, which are sometimes triggered by wine. Those are special cases, and you should be talking to a doctor about them anyway. We’re talking about otherwise headache-free people who drink a glass of wine and are seized by headaches.”

That article explored sulfites as the culprit, since so many people attribute their suffering to that preservative even though it’s found in greater concentrations in dried fruits, with which some have no problem. Winemakers often use sulfites to control some wild yeasts and bacteria that are introduced in wine through grape skins and can ruin a wine’s flavor and shorten its shelf life. Sulfites are a natural byproduct of fermentation. So there are low-sulfite wines, including some in which sulfites are not added, but there is no such thing as a no-sulfite wine. Many natural wines are made with no sulfites added or less added because winemakers believe the result is a more authentic wine.

In some people, especially asthmatics, sensitivity to sulfites can trigger severe reactions and even death. However, we quoted Dr. Frederick Freitag, then associate director of the Diamond Headache Clinic in Chicago and a board member of the National Headache Foundation, saying in 2000 what other scientists and physicians told us: “Sulfites can cause allergy and asthma symptoms, but they don’t cause headaches.”

We also explored the possibility the culprits might be histamine and tyramine, other chemical substances that are naturally present in wine. Histamine dilates blood vessels and tyramine first constricts then dilates blood vessels. Tyramine can cause your blood pressure to rise and that could trigger headaches. Tyramine is present in aged cheeses, we wrote, and smoked or cured meats and some citrus fruits. We also looked at congeners, compounds produced during fermentation. Freitag told us some people are sensitive to elements in the soils of different winemaking regions. Even compounds in the oak barrels for fermentation and aging may affect others. Headaches from red wine are more prevalent than with white wine.

So much conflicting information and still no definitive explanation. So 22 years after that 2000 column, we learned that the University of California at Davis, one of the world’s top schools for viticulture and oenology, had initiated a crowdfunding campaign to ask wine lovers to fund research to find the culprit. The idea is that if it can be identified, wine could possibly be made without it or certainly less of it.

Dr. Andrew Waterhouse, director of the Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science at UC-Davis and a professor in the university’s department of viticulture and enology, is the project lead. He also holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Bordeaux. The project was also to involve two others, Dr. Morris Levin, chief of the Division of Headache Medicine and director of the Headache Center at UCSF Medical Center, and Dr. Oliver Fiehn, director of the West Coast Metabolomics Center at UC-Davis. Headache suffers were to be interviewed and research done with a lot of wine to investigate thousands of compounds.

The month-long crowdfunding campaign in February ended with just $4,050 or 16% of the goal of $25,000 raised, so the scope and methodology have changed, Waterhouse said this week. (The site notes that there were 36 donors and that if others want to give, donations are still being accepted. Waterhouse said maybe those could be made to UC-Davis and earmarked for the study.)

“So we can’t do what we originally planned but can do a slightly different, a less expensive approach,” Waterhouse said. “I’m surprised we didn’t get more money. Apparently, it’s hard to raise a lot of money with crowdfunding.” He had initially wanted to raise $50,000 as opposed to the university’s suggested goal of $10,000. The $25,000 was a compromise, still too high a sum, it turns out.

So at the moment, instead of Dr. Levin interviewing dozens of participants about their red-wine headaches (RWH) and Dr. Fiehn identifying chemical components in dozens of wines that figure in RWH experiences, a post-doctoral student who is arriving in May, mostly to work on another project, will spend some time helping solve this mystery, Waterhouse said.

Being an intrepid sort, Waterhouse began to think of what he could do with $4,000. There is a pathway through which bodies metabolize or break down alcohol so that it can be eliminated from the body, he said. Enzymes do this work and when it happens as it should, a compound called acetaldehyde can leave the body quickly. Waterhouse said that when that pathway is blocked and the body has to contend with high concentrations of acetaldehyde, that can lead to headaches, hangovers and nausea, conditions that would discourage consumption of alcohol. This is how some medications that treat alcoholism work, he said.

“So we can pursue this basic question. We know this pathway, we can buy the enzyme. Look at the chemicals that appear in red wine,” such as the phenolics, the compounds from every part of the grape that affect a wine’s color, taste, and mouthfeel. “It’s simple biochemical research, a simple test-tube process instead of getting people involved, analyzing hundreds of wines for thousands of components.” The research still will require the participation of a few RWH sufferers.

A couple questions intrigued us in 2000 about the lack of progress in figuring out why some people suffered headaches after drinking wine. We were told then that there are dedicated opponents to alcohol consumption, no matter how moderate the consumption, inside and outside government. Modern prohibitionists are mounting efforts right now to further flag wine and other beverage alcohol as injurious to your health.

“If we don’t do anything to offer a counter argument, within the decade we should expect to see cancer warnings on wine bottles, no matter what the science proves. This type of labeling was adopted as law in Ireland in 2018 and in the Yukon Territories in 2020 and is being pursued in numerous other countries,” wrote Rob McMillan, executive vice president and founder of Silicon Valley Bank’s Wine Division, in his State of the U.S. Wine Industry 2022 report.

Waterhouse said his colleague, Levin, thought that government should help fund the research into wine headaches. “He’s a headache specialist, a neurologist. He thinks government should spend more money on headaches. They are disabling for people who have migraines and there’s not very much being spent to research this,” Waterhouse said. “With researching red wine headaches, he thinks it would discover clues to other headaches.

“From my perspective, red wine headaches are not a medical crisis on a national level and I think that the people who enjoy wine and have this issue maybe they should put some money on the table,” Waterhouse said.

“From my perspective, red wine headaches are not a medical crisis on a national level and I think that the people who enjoy wine and have this issue maybe they should put some money on the table,” Waterhouse said.

In 2000, when we asked the Wine Institute, the California-based industry advocate, about the issue, it sent us a 1996 paper on wines and headaches by Mark A. Daeschel, then professor of Food Science and Technology at Oregon State University. When we tracked him down, he told us, “There’s really nobody out there who wants to support the type of research that needs to be done to definitely nail all of this down. We can’t go to the federal government. They’ll say ‘just stop drinking.’ And wineries are hesitant because they don’t want to raise the issue that there may be a problem. But it’s a complex situation. It’s a combination of things and also the physiology of the consumer. Some people’s triggers go off quicker than others’.”

And Frietag said even if you remove alcohol from wine altogether, as some beverages market themselves today, you “may not remove the headache-related factors from a wine.”

The public has real skin in the game, Waterhouse said. “Wine drinkers are protected against heart disease pretty well, not completely. But they have much lower mortality rates than nondrinkers. There are many studies that show this very clearly.”

In 2000, we quoted researchers suggesting one way to avoid headaches is drink in moderation and with food. Some doctors suggested taking antihistamines, ibuprofen or aspirin before you drink, as an effective way to prevent headaches. But they cautioned that because some people can have harmful reactions with alcohol and over-the-counter drugs, they should first consult their doctors. Because dehydration can cause headaches, drinking a lot of water when you’re having wine is also a good idea.

We believe in science. Waterhouse or someone else will figure this out. But our bottom line 22 years ago and right now is the same: If headaches are preventing you from fully enjoying wine, you really should talk to your doctor.

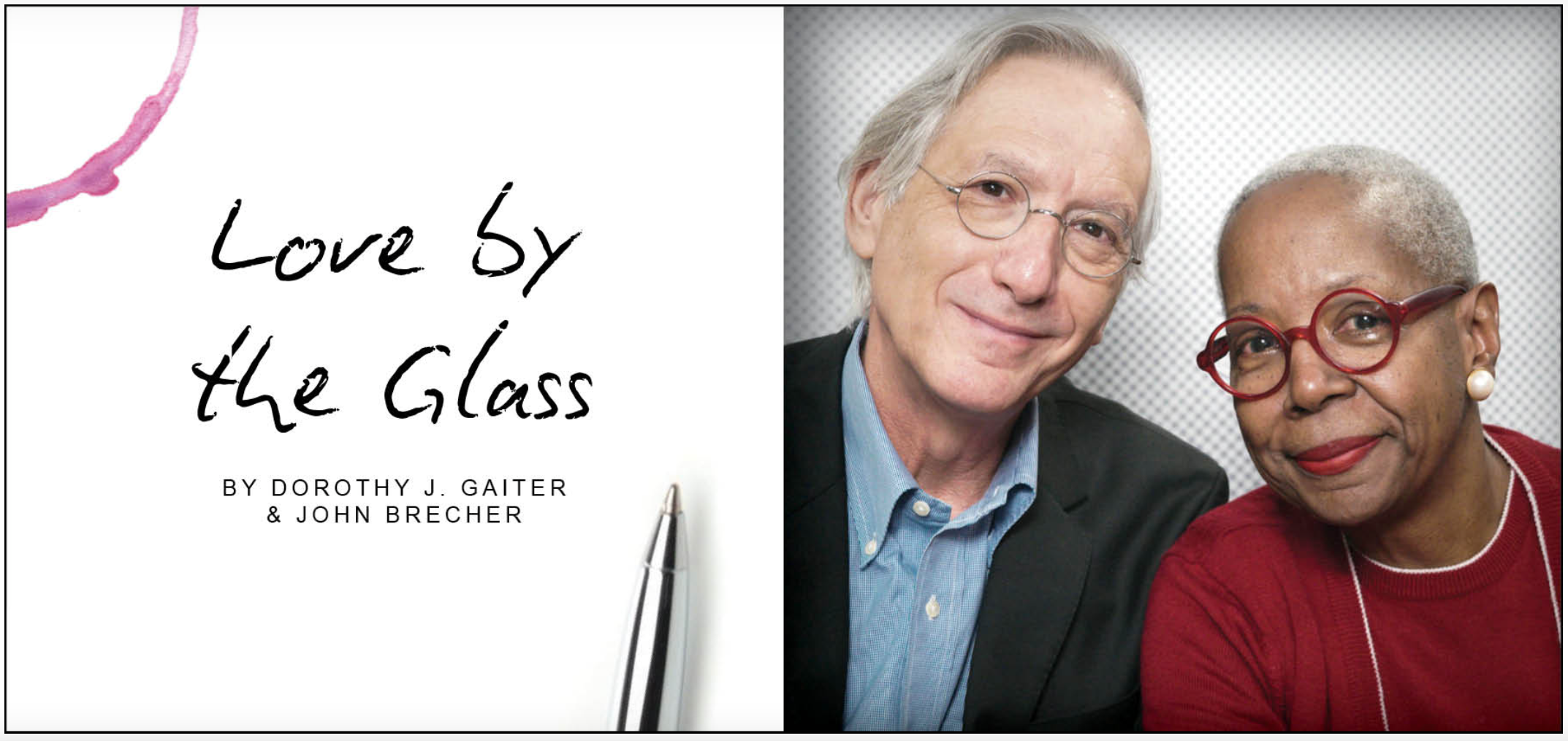

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett