Springtime in the Piemonte region is beauty personified. The landscape is a blanket of green, with hazelnut orchards in the valleys and vineyards that march up to the summits of the rolling hills, many of which are topped with tiny villages marked by roofs of red-clay tiles and church steeples. The majestic Italian Alps rear their high snow-capped peaks in the distance.

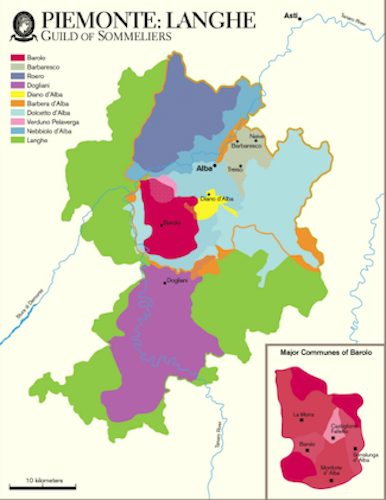

We spent several weeks taking in the beauty of the region and visiting women winemakers in the Piemonte areas of Asti and Langhe, the latter a UNESCO World Heritage site that includes the Barolo, Dolcetto d’Alba, and Barbaresco d’Alba regions (see map). Located in northern Italy just west of Milan, Piemonte ranks sixth largest in the country’s wine production and is well known for the high quality of its wines; it produces more DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) designated wine (Italy’s top wine classification) than any other region of the country. Its Barolo, Barbaresco, and Barbera wines, in particular, receive considerable worldwide attention. Over half the wines produced are exported to other countries.

We spent several weeks taking in the beauty of the region and visiting women winemakers in the Piemonte areas of Asti and Langhe, the latter a UNESCO World Heritage site that includes the Barolo, Dolcetto d’Alba, and Barbaresco d’Alba regions (see map). Located in northern Italy just west of Milan, Piemonte ranks sixth largest in the country’s wine production and is well known for the high quality of its wines; it produces more DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) designated wine (Italy’s top wine classification) than any other region of the country. Its Barolo, Barbaresco, and Barbera wines, in particular, receive considerable worldwide attention. Over half the wines produced are exported to other countries.

Why We Visited

We study women winemakers in major wine regions and what facilitates their success in the male-dominated field of winemaking. Reporting on prominent international wine regions where women are receiving increased recognition as winemakers is of particular interest.

Although Italy is known to have a masculine culture and is ranked the lowest in gender equality among the countries in the EU,1 recent wine industry publications indicate significant changes in the role of women in the Piemonte.2 We were interested in knowing more about these changes, and especially whether they extended to women wanting to break into the field of winemaking.

Some history. Wine families in the Piemonte are often multi-generational, residing at the same location for well over a century. Both legal and cultural traditions dictated that the land and the responsibility for the wine estate passed from father to son. In fact, until Italian family law changed in 1975, the father had sole paternal authority and was il "padrone" di casa (master of the house). This significant change in family law formally put an end to the hierarchical structure of family dominance by men, but the custom continued for many years, and still continues to some extent today.

As we describe later, a number of the women we interviewed noted that the prevailing attitude in their families was that as girls, there was no place for them in the estate’s winery. Others grew up under the view that, "having a girl, only girls, is a family curse."

The Women Winemakers Upending the Curse

There are many wineries in the Piemonte, and relatively few women winemakers. Through our research we were able to identify and arrange meetings with 10 women known for making high quality wine in the Barolo, Barbaresco, and Asti wine regions.3,4,5

We visited in April and May, just as the vines were bursting forth from their long winter dormancy. Warmly welcomed at each and every estate, we often met with other family members, tasted excellent wines, and visited the vineyards and cellar. Our conversations were lively and informative. We asked what ignited their interest in winemaking, and sought information about their experiences growing up and their education, career path, and the wines they crafted. Finally, we asked about their being a woman in a male-dominated field and their perceptions of how things have changed in Piemonte since the 1980s when the first women winemakers entered the field.

We visited in April and May, just as the vines were bursting forth from their long winter dormancy. Warmly welcomed at each and every estate, we often met with other family members, tasted excellent wines, and visited the vineyards and cellar. Our conversations were lively and informative. We asked what ignited their interest in winemaking, and sought information about their experiences growing up and their education, career path, and the wines they crafted. Finally, we asked about their being a woman in a male-dominated field and their perceptions of how things have changed in Piemonte since the 1980s when the first women winemakers entered the field.

(Photo: Springtime in the vineyards of Langhe)

The trailblazing women.6 Because 1975 was a pivotal year for women’s rights in Italy, we first describe the career paths of the four trailblazing women born before then. The four, born between 1959 and 1967, all needed to find a way around "tradition" and "the curse of being a woman" to pursue a career in winemaking. They are Chiara Boschis, the first woman in the Langhe to own and operate a winery, M. Cristina Oddero, the first person in Barolo to use netting to protect her vineyards from hail, Marina Marcarino, whose winery, Punset, located in the Barbaresco denomination, is the oldest organic winery in the area, and Maria Teresa Mascarello, who at age 38 was the first woman to take over an iconic estate in Barolo. We share their fascinating stories below in order of their age.

The women one generation later.6 We next describe the career paths of the six younger women. They are Silvia Altare, Emanuela Bolla, Silvia Cigliuti, Paola Rocca, Nadia Verrua, and Sara Vezza.

All 10 women grew up in wine families, and nearly all are now the winemaker for their family's original wine estate. And all were the first in their families to work full-time as winemakers managing an estate's vineyards and cellar.

Unique among the global wine areas we have studied, most of the women learned their enology and viticulture working with their families and studied other subjects during their formal schooling. Interestingly, adolescent girls and boys must decide their specialized course of study at the early age of 14; it wasn’t until the late 1970s that girls were even permitted to enroll in the highly regarded six-year enology program at the Scuola Enologica di Alba.

With regard to siblings, nearly all grew up with one or more sisters and no brothers, so clearly were in a position to upend the "curse."

The Trailblazing Women

Chiara Boschis

"I am first a farmer."

The winemaker and owner of E. Pira & Figli di Chiara Boschis located in Barolo is the passionate, talented, and determined Chiara Boschis. She is the first woman winemaker in the Langhe and also the only female member of a small group known as the "Barolo Boys" about whom more will be said later.

(Photo: Chiara Boschis)

Chiara and her three siblings, a sister and two brothers, come from eight generations of farmers. She grew up loving the land: "I have especially nice memories of the harvests. All the relatives would come and help my parents. My mom would be cooking and everyone was happy, singing, eating, and drinking at the end of the working day!"

While her brothers prepared themselves for running the family winery at some future time, Chiara, knowing that as a daughter she would be excluded from it, studied business and economics at the University of Turin. As fate would have it, in 1980, while she was still at the University, the centuries old Barolo estate of a dear friend of her parents, Luigi Piri, became available; Luigi had died and left no heirs. Chiara, who was very interested in a future in wine, convinced her parents to help her purchase E. Pira & Figli. They formed an Azienda Agricola and took out "a big mortgage together.”

Chiara worked at an international consulting firm for several years after graduation to earn money and gain experience; her father and older brother managed the winery during this period. By the mid-1980s, she was able to begin working full-time at the winery.

The situation for women today. Chiara noted that back in the late 1980s and 1990s, she was very much on her own as a winemaker. Working in the cellar was meant for men, and all the male winemakers viewed her with suspicion. "Now things have changed, and a woman competing in a man's world is no longer strange. In the EU, USA, and some Eastern Countries at least, if you have talent, and if you are also a good person, you can find the help you need and the way to grow as I did."

The vineyards and the winery. In the late 1980s, Chiara became associated with other visionary young winemakers in the area, all men, who also had realized change was needed to improve the wines of Barolo. "It was a very exciting time when I started. This group of friends and I, the Barolo Boys, as they are called now, were always exchanging suggestions and ideas. We wanted to make Barolo the best we could."

Chiara officially took over the leadership at the E. Pira & Figli winery in 1990, becoming both its owner and winemaker. She began implementing what she had learned in association with the Barolo Boys, protocols such as dropping fruit to decrease the size of the crop—a "shocking" practice at the time—thereby increasing the quality of the grapes, shorter fermentations, and using small barrels known as barriques7 to accommodate the limited amount of wine produced as single crus. She farms organically, and organic certification was obtained in 2014. Her younger brother, Giorgio, joined with Chiara in 2010 and brings his thirty years of experience to the winery.

E. Pira & Figli wines. Chiara prides herself on crafting Barolos with "approachability, balance, intense aromatics, and elegance." Dolcetto d'Alba, Barbera d'Alba, and Langhe Nebbiolo, the three traditional Piemonte reds, are also produced. Her very first wine, the 1990 Barolo Riserva Cannubi, earned the coveted Tre Bicchieri award from the Gambero Rosso. High praise has continued. Her 2010 Barolo Cannubi, for example, received a score of 96 from The Wine Advocate. (Our appointment for a tasting had to be cancelled at the last minute due to the death of Chiara’s dear father, Franco Boschis, at the age of 92.)

M. Cristina Oddero

"My joy lies in preserving the strong values of family and tradition, while also embracing research-based innovation and change."

Cristina Oddero, a scientist at heart, has learned to seek new paths when life throws her a curve ball. First a student of agronomic science and then a teacher of chemistry and biochemistry, Cristina now co-owns and manages the Oddero estate located in the Barolo area.

Cristina Oddero, a scientist at heart, has learned to seek new paths when life throws her a curve ball. First a student of agronomic science and then a teacher of chemistry and biochemistry, Cristina now co-owns and manages the Oddero estate located in the Barolo area.

(Photo: M. Cristina Oddero)

A representative of the family's sixth generation, Cristina and her older sister grew up in a wine family, although her parents, Carla and Giacomo, were both pharmacists and co-owned a pharmacy. Italian and French literature was discussed over dinner, and empathy for others was always emphasized. Giacomo was also a visionary leader in the wine community. For example, he helped bring about the procedural guidelines that gave wines of the Langhe and Roero DOC and later, DOCG certifications. In addition, her father co-owned the family estate that he and his brother, Luigi, had inherited.

Cristina attended Liceo Classico in Alba for high school and then went on to the University of Turin to study agriculture. An important aspect of her undergraduate research there concerned how various kinds of grapevine rootstock respond to the different soils in the Piemonte region. She subsequently completed a master’s degree in viticulture and enology at Turin in 1987. The subject of her thesis was malolactic bacteria in the production of Barbera wines.

Beginning in 1987, she taught soil chemistry and then chemistry and biology in Alba and married during this period. A few years after the birth of her son, Cristina decided to pursue a new path by working part-time in the cellar at the family estate; she left her teaching position in 2000 to be full-time at the winery.

Cristina and her Uncle Luigi had "some different ideas about the vineyards and the cellar" and in 2006, after a few very tense and difficult years, the two families decided to go their separate ways. They divided their nearly 60 hectares of land, with Cristina keeping the family's historic cellars in La Morra and her uncle starting his own winery. She and her older sister, Mariavittoria, a physician, are now co-owners, and Cristina’s son, Pietro, and Mariavittoria’s daughter, Isabella, have key positions at the estate. Meeting Pietro and Isabella the day of our visit was a special pleasure for us.

The situation for women today. Cristina noted that "Italy is a masculine culture and change is slow." She is encouraged by the young women today doing excellent work and feels sanguine about the future. She thinks women are better than men in certain areas of winemaking as women have learned to be more detail oriented, and controlling details is crucial in crafting top wines.

The vineyards and winery. Cristina clearly loves what she does, as she demonstrated during our enjoyable and extensive visit to the vineyards. Beehives have been placed near the vineyards consistent with the region’s designation as a UNESCO site, and the fact that 90% of their grapes are now being certified as organic. Close attention is paid to the vines from spring pruning to harvest. Cristina was the first person in the area to use netting to protect the grapes from hail, as noted earlier. Although she initially received a bit of ridicule "as a girl" for doing so, it is now a common practice.

Winemaking at Oddero combines traditional knowledge with modern methods and research. The impressive new winery, completed in 2015, uses up-to-date approaches to insulation and energy conservation. Carefully selected oak is used for aging the Barolo and Barbaresco wines. Her Barbera is aged in the traditional botti.8

Oddero wines. Oddero wines consistently receive excellent reviews from wine critics. For example the 2014 Oddero Barolo Brunate received a score of 93 from both Robert Parker and Migliori Vini d'Italia and the 2012 Barolo Villero a score of 97 from James Suckling. We tasted several gorgeous wines with Cristina, including the 2017 Langhe Nebbiolo, and the 2015 Oddero Barolo Villero.

Marina Marcarino

"My philosophy is to produce excellent wines in complete harmony with nature."

Marina Marcarino, owner and winemaker at Punset, an organic winery, is among the very few early woman winemakers in Piemonte and an early advocate of organic farming, using biodynamic techniques. Punset, located in the Barbaresco denomination, is in fact the oldest organic winery in the area.

Marina Marcarino, owner and winemaker at Punset, an organic winery, is among the very few early woman winemakers in Piemonte and an early advocate of organic farming, using biodynamic techniques. Punset, located in the Barbaresco denomination, is in fact the oldest organic winery in the area.

(Photo: Marina Marcarino)

Her love for viticulture and the environment started as a child. "My grandmother always had me in the vineyards, not in front of the TV or playing with dolls. We could see blue chemicals everywhere [farmers wanted to be modern], and saw the negative effects of spraying on the birds and butterflies." Marina entered the Scuola Enologica di Alba in 1978, at age 14, with plans to continue her studies in enology at the university in Turin. Her parents, however, wanted Marina to study engineering and join the family business. Her father and grandfather owned land and made wine only as a hobby, but the real business of the family was construction.

Marina's passion was with wine, however, and she quietly continued her oenological studies in Turin until she was "found out" for doing so. She then left the university to work in the family business. After six months of being unhappy in her work there, she approached her father with a business proposition that involved her running the family farm for one year. His response was that if she could make a profit at it, she could keep doing so.

Marina had little money, but she had a project in mind for the farm and the passion to see it through. She approached one of her former professors and asked about the possibility of assigning students as interns to assist her with the project. The professor responded that if she came up with something worthwhile and educational, he could assign student workers to her project. Her proposal was associated with organic farming, a relatively new idea for Italy in the mid-1980s, and students were assigned to the project.

Her project with the university was successful in that Marina kept the estate profitable, but the resistance to her as a woman winemaker and to implementing organic farming practices was considerable. She kept her focus and also continued to hire younger people "because of their mentality and their openness"; In her experience, "Older men are difficult to work with."

The situation for women today. Marina noted that until the 1970s "women had no value in Italy." Girls (her only sibling is an older sister) were left out of the inheritance of land and were expected to marry and care for children and husbands. When she started at age 19 in 1983, things were very different from today: The mentality for years and years was "women are not capable."

It is her belief that it is very rare for winemakers who are women to get a job at a winery that is not owned by her family. Similar to Cristina Oddero, she thinks women are better in certain areas of winemaking "because of their socialization."

The vineyards and winery. Through commitment and tenacity, Marina has forged a respected space for her philosophy and her wines, "within the conservative and very masculine world of viticulture and winemaking." In 2012, Wine Spectator listed her 2007 Barbaresco among the Best 100 Wines. This highly significant recognition brought Marina and her wines the respect they had long deserved. Two years later, in 2014, Coldiretti (Italy's national association of farmers) began to promote organic practices and chose Punset for a field trail. The visit of many growers to the Punset vineyards raised awareness of organic practices and further increased her stature in the region.

Punset wines. The Punset wines, which we unfortunately did not have time to taste, receive consistently strong reviews from wine critics, especially the winery’s Barbarescos. As an example, the 2007 Punset Barbaresco was awarded 95 points by Wine Spectator.

Maria Teresa Mascarello

"I have a big responsibility."

Maria Teresa Mascarello, who owns and runs her family’s iconic Barolo winery, Bartolo Mascarello, is a bit of an anomaly in the male-dominated world of wine. She began working in her family’s winery in 1993 when she was 26 years old. "The environment was very masculine and women were always marginalized." Nonetheless, she persisted carrying on the winemaking traditions of her father with great aplomb, much to the surprise of those who were waiting for her to fail.

Maria Teresa Mascarello, who owns and runs her family’s iconic Barolo winery, Bartolo Mascarello, is a bit of an anomaly in the male-dominated world of wine. She began working in her family’s winery in 1993 when she was 26 years old. "The environment was very masculine and women were always marginalized." Nonetheless, she persisted carrying on the winemaking traditions of her father with great aplomb, much to the surprise of those who were waiting for her to fail.

(Photo: Maria Teresa Mascarello)

Maria Teresa grew up in a celebrated wine family but remarkably, wine did not interest her. Her parents allowed her to make her own decisions, and Maria Teresa chose to attend Liceo Scientifico in Alba and then to study foreign languages, namely, French and German, at the University of Turin.

As a daughter, she was not expected to be able to carry on with her father’s work, but as an only child, she began to feel a responsibility to do so. Her grandfather had produced his first Barolo in 1919, and his knowledge and use of the traditional methods was passed on to her father, who was now producing great Barolo. Maria Teresa felt a commitment to continuing her family’s work and traditions.

In 1993, she began learning the business from her parents, who were then already in their 60s. (Her father, also an only child, was 41 when she was born.) Her father became her teacher in both the vineyards and the cellar. When his health began to decline in the late 1990s, Maria Teresa began taking on more and more of the work in the vineyards and cellar, and she was taking nearly full responsibility by 2004 (her father passed in March 2005).

Her first vintage was produced in 2005, when she was only 38 years old, and received rave reviews. Antonio Galloni’s Vinous awarded the 2005 Barolo 95 points, describing it as “a gorgeous wine.” Wine reviewers consistently describe her Barolo as having a harmony and elegance that surpasses the great vintages of earlier years.

The situation for women today. Maria Teresa believes that men today are more open to women’s abilities, and that women are più bravo. She sees women as more free to decide their futures, and believes the current generation may finally be experiencing a shift in women's rights in Italy.

When she was born in 1967, as the first and only child of older parents, her father, Bartolo, refused to come to see her in the hospital: "to have a girl is like a woman being barren." Her father's family also refused to have her named Giulia after Bartolo's father, Giulio, a tradition they reserved for a son. This masculine attitude continued. When she began working with her parents years later, "Women were paid no salary for their work and were also expected to raise the children."

Similar to Cristina Oddero and Marina Marcarino, Maria Teresa also noted that there are many more men than women in the cellar still today, but also that "women have a greater sensibility about wine, they pay more attention to nature and have respect for it. Women have to see 360 degrees."

The vineyards and winery. Maria Teresa continues to run the winery according to her father and grandfather’s traditional methods. Indigenous yeasts and long fermentation and maceration times are used. Fermentation occurs in glass-lined concrete tanks with no temperature control, and wines are aged exclusively in botti,8 rather than the smaller barriques7 favored by the "modernists." Indeed, Bartolo was such a "traditionalist" that he once produced a hand-painted label stating, "No Barrique, No Berlusconi," a statement of his aversion to the smaller barrels being introduced by the modernists and to the political leadership in Italy at the time.

Bartolo Mascarello wines. The estate’s Barolo wines are particularly well known and receive very positive reviews from Italian and international wine critics. Wine Spectator listed the 2010 Barolo among the world’s 100 top wines. We were pleased to taste the 2016 Bartolo Mascarello Langhe Nebbiolo, with its bright fruit and wonderful aromas, and the elegant 2014 Bartolo Mascarello Barolo, which recently received 95 points from Wine Enthusiast and 94+ points from Vinous.

The Women, One Generation Later

We now turn to the six younger women, all born between 1977 and 1982, and presented below in alphabetical order. Three of these women craft their wines in the Barolo region, two in the Barbaresco region, and one in the Asti region. They are Silvia Altare of Elio Altare and Emanuela Bolla of Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno (Barolo), Silvia Cigliuti of Fratelli Cigliuti and Paula Roccaof Albino Rocca (Barbaresco), Nadia Verrua of Cascina 'Tavijn (Asti), and Sara Vezza of Josetta Saffirio (Barolo).

Silvia Altare

"Revolution is from wine being part of the culture."

Silvia Altare, a young woman of great radiance, intelligence and wit, is now the owner and winemaker of Elio Altare located in the Barolo region. She grew up in a wine family made famous by her father, Elio, who in the mid-1970s was one of the Barolo Boys who dared make wine more like the French Burgundians do. Elio and Lucia’s two children, Silvia and Elena, however, were never pressured to involve themselves with winemaking. In the early 1980s, that was a future reserved for boys.

Silvia Altare, a young woman of great radiance, intelligence and wit, is now the owner and winemaker of Elio Altare located in the Barolo region. She grew up in a wine family made famous by her father, Elio, who in the mid-1970s was one of the Barolo Boys who dared make wine more like the French Burgundians do. Elio and Lucia’s two children, Silvia and Elena, however, were never pressured to involve themselves with winemaking. In the early 1980s, that was a future reserved for boys.

(Photo: Silvia Altare)

Growing up, Silvia participated in the various aspects of winegrowing and winemaking with her family but often felt that she had to prove herself as a girl. Starting in 1994, when she was 15, her parents sent her to live with a family in California for the summer. She helped with their five children and loved it so much that she returned for the next eight summers. "I was the rock star of the village" (relatively few people leave her small village for California!). For high school, Silvia enrolled in the Liceo Classico in Alba, taking the humanistic and economics paths, not the science and enologa routes. She then attended the University in Turin and studied international business, graduating in 2003.

Interestingly, her summers in California were with a family that had started its own winemaking adventure, Sine Qua Non, in 1994, the same year Silvia first went to California. They were successful and their wines are quite well known. This fortuitous connection led Silvia to travel to other wine areas in California and to work harvests in other countries. When she graduated from the university, it was clear that she would be joining the family estate.

Her younger sister Elena, who studied languages, moved to Germany, where she married in 2006 and now lives with her family. She represents the Elio Altare brand in Germany and also runs a wine importing company.

The situation for women today. Silvia's superhero is Chiara Boschis, the first woman winemaker in Barolo. "I look at her photo every day and say I want to be just like you." And truth be told, she is! "One needs the passion from inside. It is so intense."

Silvia describes Italy "as a macho country" and knows first-hand what it was like growing up needing to prove oneself when one is not born a son. At the same time, she is hopeful and sees her generation as making a difference. "Today there are fewer mama's boys who need a woman to do everything for them."

The vineyards and winery. Silvia purchased the winery from her parents and sister in 2016 but is continuing the family-run structure and traditional approach to viticulture and winemaking. The vineyards are cultivated without the use of chemicals and pesticides and "the wines are simple and natural." She, her parents, and a small staff manage the vineyards, the cellar, and sales and marketing. Elio, still energetic and creative, enjoys mesmerizing visitors with the accomplishments of the Barolo Boys.

As one of the Barolo Boys, Elio took things in a radical direction in his own father's cellar after a trip with a few friends to Burgundy in the mid-1970s convinced him that barriques7 rather than botti8 should be used for aging wines. His father was so upset with the break from tradition that he disinherited his son! Undaunted, Elio continued to work while he ultimately bought back the winery and vineyards from his siblings.

Elio Altare wines. We participated in a most enjoyable tasting with Silvia that included the 2016 Barbera d'Alba and the 2015 Barolo and 2015 Barolo Aborina. Known for their elegance and balance, the Altare wines consistently receive top reviews from Italian and international wine critics. The 2010 Barolo, for example, received a score of 94 from Robert Parker, and a 93 from Wine Spectator, and the 2007 Barolo Arborina, a score of 96 from Parker.

Emanuela Bolla

"My love is for the vineyards and the cellars."

The charismatic Emanuela Bolla, winemaker at Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno in Barolo, is a fifth-generation family member. She grew up having a special relationship with, Serio Borgogno, her nonno and the family’s long-time widely respected winemaker.

The charismatic Emanuela Bolla, winemaker at Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno in Barolo, is a fifth-generation family member. She grew up having a special relationship with, Serio Borgogno, her nonno and the family’s long-time widely respected winemaker.

(Photo: Emanuela Bolla)

Emanuela has three siblings, all sisters. She told us that, "luckily the family did not expect me to work at the winery. I was able to come to my own decision." She left home for Turin to study architecture, another of her passions, and met her future husband there in 2006. It was not until after completing her degree that the strong influence of her special relationship with her grandfather became apparent, as well as her own love for the vineyards and cellar: "I realized that I wanted to stay here." She studied with a friend, an enologa, and then in 2010 became part of the family business, working for a year with her grandfather in the vineyards. In 2012, she joined her father, Marco Bolla, in the cellar, "My curiosity brought me to learn from my father the art of making wine."

The situation for women today. Emanuela believes that the big change in the Piemonte region is that women in wine families are taking a more visible role. "In the past men and women worked together and the men usually were the boss of the cellar. Today more women are the boss in the cellar." She went on to state that "for me there is no difference between women and men" but that was not the case for my grandparents. As a woman, "my grandmother cooked lunch for 10 people, took care of the children, and delivered the wine."

She noted that in the Langhe, the women who work in the cellars are from the family and the other employees are usually men. "If you are part of family, you can try work in the vineyards and cellar. It is more simple for the family members as their work is not defined by contract." In her experience, the women who study enology but are not from wine families are typically employed in tasting rooms and sales and marketing.

The vineyards and winery. Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno is located at the very top of Cannubi, surrounded by its stunning vineyards, which we had the opportunity to visit on a beautiful clear morning. Emanuela explained, and demonstrated, how every vine in the vineyards is considered unique and thus treated differently. The goal is to produce healthy, high-quality fruit and also protect the biodiversity that makes their vineyards so special. Organic practices are followed, and the estate is entirely family run.

While touring the extensive cellar, we learned about the importance of following traditions when making the estate's wine. The family believes that the characteristics of the different vineyards and vintages need to be conserved in the winemaking process. Wines are fermented in big wooden vats called "Tini" and then transferred to botti for aging, the "traditional" way of making wine in the Piemonte. (Serio, who died in 2016, did not favor using barriques7 for aging wine, deciding instead to continue his winery's tradition and authenticity by using botti.8)

Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno wines. The estate's Barolo, Barbaresco, and Nebbiolo are all highly regarded. The 2008 Barolo Cannubi Riserva, for example, received a score of 95 from Wine Spectator and was awarded a silver medal at the 2014 International Wine & Spirit Competition (IWSC). We tasted the 2016 Nebbiolo d'Alba, the 2015 Barolo Cannubi, and the 2013 Barolo Cannubi Riserva, very different from one another but all full-boded and luscious.

Silvia Cigliuti

"If you want to produce great wine, you need to know how to treat the plants and the soil. If a vine dies, what do you do?"

Silvia Cigliuti, the winemaker for Fratelli Cigliuti in the Barbaresco region, is a "no-nonsense" person who conveys tons of warmth. The morning we arrived, she gave us a quick wave and then returned to join the two women steadily moving cases of wine to a truck for shipping; the women were her mother, Dina, and her older sister, Claudia.

Silvia Cigliuti, the winemaker for Fratelli Cigliuti in the Barbaresco region, is a "no-nonsense" person who conveys tons of warmth. The morning we arrived, she gave us a quick wave and then returned to join the two women steadily moving cases of wine to a truck for shipping; the women were her mother, Dina, and her older sister, Claudia.

(Photo: Silvia Cigliuti)

As young children, Silvia and her sister helped their father, Renato, put on labels and then as they got older, worked in the vineyard during the summer. When Silvia was 15, she began helping her father in the cellar, mostly with racking wines.

Apparently Renato was surprised that his daughters, his only two children, were interested in returning to the land, but his daughters were not the least bit surprised.

Silvia enrolled in the Scuola Enologica di Alba at the usual age of 14 and went into its viticulture program ostensibly because she could not stand being around girls who gossiped; the truth of the matter was that she loved the plants and the soil. She graduated in 2000 and immediately came to work at Fratelli Cigliuti, the estate of her parents. Her older sister, Claudia, studied languages and worked for a few years in marketing before returning full-time to the family estate. As Silvia explained, "it is normal to stay here. We are the next generation."

The situation for women today. Silvia noted that parents in wine families today focus their children on marketing their wines, particularly their daughters. Finding Italian women or men to work in the vineyards can be difficult. It is her experience that, "Italian men prefer cellar work and have little interest in the vineyards." Indeed harvest workers in the area typically come from other countries. "If one says they want to work in the vineyard, male or female, they will be hired."

When asked if they have ever employed women in the cellar, her response was, "We have no Italian women in the cellar, as none have applied."

The vineyards and winery. Silvia and her sister work together very well and now manage the estate, with Renato and Dina supervising. The family’s mantra is that 90% of the winemaking process happens in the vineyard, which is farmed using organic practices. Manipulation in the cellar is kept to a bare minimum; indigenous rather than commercial yeasts are used, grapes are fermented in stainless steel vats at controlled temperatures; and wines are aged in Slovenian and French oak barrels and casks.

Family is very important to Silvia. She and her sister are both married, and they each have two children. Their two families, as well as their parents, all live in separate houses on the family estate. The day we were visiting, we stayed longer than we had planned, and Silvia let us know that she was pressed for time. The reason was that the families all have lunch together, and noon was approaching. This tradition reflects well on the family closeness and compatibility characterizing Fratelli Cigliuti.

Fratelli Cigliuti wines. Before touring their impressive cellars, we had the opportunity to taste both the excellent 2016 Campass Barbera d'Alba and 2015 Serraboella Barbaresco. The estate’s Serraboella Barbaresco and Barbera wines have a highly reputable history dating back to Silvia’s father, whom we met briefly. He is a youthful 81-year-old farmer and winemaker who dared to begin green harvesting, a practice utilized by very few producers at the time. Knowing that he had to choose between quality and quantity, he went for quality. The 2010 Cigliuti Barbaresco, for example, earned a score of 95 points from Wine Spectator and its 2012 vintage a score of 94.

Paola Rocca

"Most important is the land, the family, continuing the land, and the need to find the right balance with size."

The energetic and radiant Paola Rocca, the winemaker for Albino Rocca in Barbaresco, grew up surrounded with wine. From a very young age she remembers being happy in the cellar working with her father, Angelo Rocca, and the joy of crushing grapes with her feet. The youngest of three children, all daughters, she was the only child who knew early on that her passion was with wine.

The energetic and radiant Paola Rocca, the winemaker for Albino Rocca in Barbaresco, grew up surrounded with wine. From a very young age she remembers being happy in the cellar working with her father, Angelo Rocca, and the joy of crushing grapes with her feet. The youngest of three children, all daughters, she was the only child who knew early on that her passion was with wine.

(Photo: Paola Rocca)

Paola enrolled in the Scuola Enologica di Alba at 14 and graduated from its rigorous six-year program in 2002. Only 20 at the time, she immediately began working full-time as an enologa with her father at the family winery. To the great surprise of her family, the next year, at only 21, she married Carlo Castellengo, the son of another Barbaresco wine family and an enologo as well, who had been mentored by her father and was five years her senior. Paola’s older sister, Monica, who graciously assisted with translations during our conversation, told us that she cried and cried at her wedding. "Paola was so young!"

The situation for women today. Monica and Paola noted that, as a more recent wine region, the Piemonte may be more open to women's participation than Italy's older wine regions. Paola, who observed her mother and father working in the vineyards and cellar, added that "one's parents love and passion for their work can inspire their daughters."

The vineyards and winery. Paola works hand in hand with Carlo in the vineyards and cellar: "We share all aspects of the viticulture and vinification." They make for a passionate and loving team. They are implementing sustainable farming practices and focusing on quality and finding the right balance for the size of their estate. No machines are used for harvest, and the same four employees have worked at Albino Rocca for 20 years.

Carlo, who had worked part-time with the family for a number of years while also working full-time at his father's nearby winery, came on full-time after the death of Angelo Rocca in 2012; Angelo was tragically killed in the crash of his private plane. Paola's two older sisters have also returned to the family business. Daniela, the eldest daughter, returned in 2010 after a successful career in banking, and Monica, who studied law, joined the family team in 2007. Daniela and Monica handle the sales and marketing for Albino Rocca.

Paola totally embraces the complexity and difficulty of her work. She sees the characteristics of her success "as pleasure in my work and love for the land and for my family." Paola and Carlo's two sons, born in 2005 and 2009, respectively, work in the vineyards during the summer, and hopefully will inherit their parents' passion for enology and viticulture and for preserving the land.

Albino Rocca wines. Paola's eyes sparkled when we toured their extensive cellars and tasted her and Carlo's fresh and fruity 2018 Langhe Chardonnay da Bertu and their elegant 2015 Barbaresco Montersino. Indeed, Albino Rocca is widely recognized as a producer of elegant Barbarescos. The 2015 Barbaresco Vigna Loreto Ovello, for example, received a score of 96 from Wine Spectator, and both the 2015 Barbaresco Montersino and 2015 Barbaresco Ronchi earned scores of 92.

Nadia Verrua

"Winemakers are viewed as more elite [than farmers] and thus more able to start changes for more sustainable farming."

The artistic, personable, and determined Nadia Verrua of Cascina 'Tavijn is now its owner and winemaker. Indeed, had it not been for her determination and strength of character, Cascina 'Tavjin located in the Asti province of the Piedmonte region would not exist today.

The artistic, personable, and determined Nadia Verrua of Cascina 'Tavijn is now its owner and winemaker. Indeed, had it not been for her determination and strength of character, Cascina 'Tavjin located in the Asti province of the Piedmonte region would not exist today.

(Photo: Nadia Verrua)

Twenty years ago, the Verrua family, which had worked the Cascina 'Tavjin vineyards and cellar since 1908, seriously considered selling their land. Nadia’s parents were tired, and their three children, all daughters, were grown and had studied in areas unrelated to agriculture. Moreover, as noted earlier, it was not part of the culture and tradition to pass the management of vineyards and the production of wine to female children.

Nadia, the middle daughter, studied art, but she also had a strong connection to the land and wanted to work with her parents to continue the estate. Not unlike other wine families of the Piemonte region having only daughters, Ottavio, her father, was reluctant to let her participate in winemaking. However, Teresa, her mother, with whom Nadia had worked in the cellar over the years, persisted in her support of Nadia's involvement. Her father ultimately agreed to let Nadia start with a production of 1000 bottles, all of which quickly sold. Her first independently bottled vintage was in 2001.

The situation for women today. When asked about this, Nadia said, "there are not really a lot of women." She sees two different groups (1) younger women trained to make wine and know what needs to be done but may have limited opportunities in getting wine-making positions, and (2) similar to her situation, women in wine families who learn mostly from their parents and became part of the winemaking team.

The vineyards and winery. Nadia now runs the small family cellar of Cascina 'Tavjin, and she and her father jointly care for the vineyards and hazelnut trees that are planted on the property. Vines are cultivated using bioorganic methods, grapes are harvested by hand, and only botti8 are used for aging the wines. Nadia favors spontaneous fermentations with native yeasts and performs this stage of vinifying in either fiberglass or concrete tanks.

Being with Nadia is somewhat like being caught in a whirlwind. She is in constant motion! Within only two short hours, we met her father, visited the cellar, talked with her two school-aged children and her mother, all while Nadia was engaged in putting her own beautifully designed labels on some wine bottles, handling phone orders, and carrying on a thoughtful conversation with us. Her husband is not involved with the winery and manages his own restaurant, Consorzio, in Torino (Turin). Among other notable wines of Italy, it features her wines, of course.

Cascina 'Tavijn wines. Nadia crafts wines from three varietals: Barbera, Ruchè, and Grignolino. Her Cascina 'Tavijn Bandita Barbera d’Asti receives consistently high praise and is described as refreshing and lean with focused flavors. We greatly enjoyed her elegant and approachable 2017 Vino Rosso "Teresa"- Cascina 'Tavijn, a Ruchè named for her mother, whom she greatly admires, and with good reason.

Sara Vezza

"I hope to tell you my joy through my wine."

The remarkable Sara Vezza of Josetta Saffirio is totally committed to working with Mother Nature. She grew up as a representative of the fifth generation of an agricultural family in Monforte d'Alba, a municipality in Piemonte where Barolo wine is produced. The family had cultivated and sold their grapes for many years. In 1975, Ernesto Saffirio, Sara's grandfather, asked his daughter, Josetta, who had studied agriculture, and her husband, Roberto, an oenologist to tend the family vineyards. They began producing small quantities of excellent Barolo from their grapes in the 1980s.

The remarkable Sara Vezza of Josetta Saffirio is totally committed to working with Mother Nature. She grew up as a representative of the fifth generation of an agricultural family in Monforte d'Alba, a municipality in Piemonte where Barolo wine is produced. The family had cultivated and sold their grapes for many years. In 1975, Ernesto Saffirio, Sara's grandfather, asked his daughter, Josetta, who had studied agriculture, and her husband, Roberto, an oenologist to tend the family vineyards. They began producing small quantities of excellent Barolo from their grapes in the 1980s.

(Photo: Sara Vezza)

All this changed in 1992 when Sara was 12 and her younger brother was 11. The winery was closed and the vineyards were rented. It was too much for her parents to continue to manage the vineyards and winery in addition to their other responsibilities.

Sara loved the vineyards and working with nature. In 1999, at age 19, she started helping her father to crush grapes, and when she completed her university studies, returned to the family estate full-time. She devoted herself to using sustainable methods in the vineyards and also started working with her father in the cellar.

The situation for women today. Sara is totally immersed in managing the estate and family matters, including childrearing. She thinks women are treated as equals today and appreciates how things have changed from earlier times.

The vineyards and winery. In 2006, the family built an impressive sustainable cellar, integrated with the surroundings and insulated with natural cork; Sara now uses the facility for vinifying the Josetta Saffirio wines. Her focus on sustainable solutions and technologies resulted in the winery’s receiving a Sustainable Certification in 2015 and being granted Organic Certification in 2017. She, her father, and four employees manage the several colonies of bees kept on the property as well. Sara and her husband, who works at a different wine estate, have four children. Sara delights in introducing them to nature on their many walks in the beautiful countryside surrounding the estate.

Josetta Saffirio wines. There was not time to taste her wines, especially her Barolos, which consistently receive high praise from wine critics. The 2008 Barolo Persiera, for example, was awarded 94 points by the Wine Advocate and the 2004 Barolo Persiera, 93 points.

In 2009, Sara and her father began experimenting with a sparkling wine-a 100% Nebbiolo vinified according to the Classic Method (methode Champenois). "I gradually began to understand that Nebbiolo isn't just perfect for the production of great reds like Barolo, it’s ideal for making sparkling wine too." The 2016 Josetta Saffirio Brut Rosé (Nebbiolo d'Alba) garnered 89 points from the Wine Enthusiast, which said, "Delicately scented, this has aromas evoking spring field flower, red berry, orchard fruit and a whiff of bread dough."

More on the Grape Varietals, the Wines Produced, and the "Barriques"

The main varietals of grapes favored in Piemonte are Dolcetto, Barbera, and Nebbiolo, although lesser-known varietals such as Aneis, Ruché, and Cortese, among others, are also produced. Nebbiolo is the foundation for two well-known wines from the region, Barbaresco and Barolo, and it is variation in the vinification of the juice that differentiates the three wines. Specifically, Nebbiolo results from skin contact of the juice for two to three weeks, aging for six months or more in stainless steel, wood, or concrete, and finally a year or so in the bottle. Barbaresco normale is aged for 26 months, and the Riserva for 50 months; for both, nine months of aging is in wood. For Barolo, the normale is aged for 38 months and the Reserva for 62 months. For Barolo, the normale is aged for 38 months and the Reserva for 62 months, with a minimum of 18 months in wood for each.

The "barriques" saga, an on-going controversy. The barrels used for aging are commonly made of oak, but other woods such as chestnut may be used. They vary in size, however, and this has been a source of controversy in the region. Vintners who are traditionalists use the huge botti8 that may be used over and over for decades. Modernists, on the other hand, inspired by the practices of Burgundian winemakers, foreswear the botti in favor of the much smaller barriques.7

The use of barriques began in the mid-1980s and was promoted by a group of winemakers who came to be known as the Barolo Boys, something of a misnomer because, as noted earlier, Chiara Boschis is one of the five members of the group. Also as noted earlier, one of these "Boys," Elio Altare, became so frustrated with his father’s unwillingness to abandon the traditional use of botti for aging, that he took a chain saw to them, converting the large barrels to firewood. In any case, using barriques was considered revolutionary at the time. Among the arguments favoring their use is that the smaller barrels impart more of their flavors to the wines during the aging period. Whether the traditionalist or modernist approach results in better wines remains a subject of disagreement among Piemontese winemakers even today.

Let's Celebrate the Curse "Upended" and the Women Who Made It Happen

We believe that sharing the inspiring stories of these successful women will further facilitate the process of change that clearly is underway in the Piemonte-Langhe region. Without exception, all 10 women love what they do and care deeply about the future of the region.

Four important themes emerged from our inspiring conversations.

- First, as a group, all these winemakers are proud stewards of the land they love and are proud builders on what their families have accomplished over past generations. All but one winemaker works closely with members of her family, and several work in the cellar with a brother, father, or spouse.

- Second, "to upend the curse," all of the trailblazers and most of the first-generation winemakers had to convince their fathers that as daughters they were capable of continuing the family's traditions in the vineyards and cellars. Their passion, talent, and determination were crucial in this process.

- Third, they "upended the curse" by becoming highly respected winemakers. They accomplished this by learning their craft through formal schooling and/or by working alongside experienced winemakers, often their own fathers. All of their wineries produce wines receiving top reviews from Italian and international wine critics, including wines appearing in Wine Spectator's "Best 100 Wines."

- Fourth, they have demonstrated that women are just as capable as men in the cellar.

Important cultural change is being brought about by women in the Piemonte-Langhe since the significant changes in the law in 1975. They are becoming more visible in enology programs and in the wine business as oenologists, sommeliers, sales and marketing managers, and as producers and marketers of their family's wines.

The women we talked with clearly understand that further change is needed and that they are part of the change. As Maria Teresa Mascarello reminded us, "In teoria dovremmo essere alla pari ma corri cavallo!" ("In theory we should be equal...but there is still much territory to be covered to get there.")

In toasting the 10 trailblazing and first-generation women, we are reminded of an old Italian proverb: la fortuna aiuta gli audaci (fortune favours the brave.)

To all of these women, we wish you well and feel privileged to have had time with you and your families.

Footnotes

1. The policy on gender equity in Italy (2014): EU document IPOL-FEMM_NT(2014)493052_EN.pdf, p. 10.

2. Examples include Wine Spectator, October 31, 2018, and the book, Labor of Love, by Suzanne Hoffman (2016).

3. Opus Vino: The World’s Greatest Wineries and their Wines, edited by Jim Gordon (2010), and Michelin’s Wine Trails of Italy (2016) were used to identify winemakers in the Piemonte who are women.

4. We were unable to arrange visits with Marta and Carlotta Rinaldi of Giuseppe Rinaldi in Barolo. Marta Rinaldi is a winemaker who joined her father full-time in 2009.

5. We also made advance appointments and enjoyed informative conversations with Luisa Rocca of Bruno Rocca (Barbaresco) and her assistant, Giulia Barberis, and Anna Abbona and her daughter, Valentina, of Marchesi di Barolo. Luisa heads up Bruno Rocca's communication, sales and hospitality, both internationally and within Italy, and her brother Francesco manages the vineyards and the winery. Giulia Barberis, in addition to her work at Bruno Rocca, is a sommelier.

Anna Abbona, a co-owner with her husband, is involved in all aspects of Marchesi di Barolo and especially takes pride in Foresteria dei Marchesi di Barolo, her elegant restaurant located adjacent to the winery. Valentina Abbono, who studied International Markets, heads up international sales and marketing for both Marchesi di Barolo and Az. Agr. Cascina Bruciata in Barbaresco, a property the family purchased in 2016.

In addition, we met briefly with Bruna Ferro of Az. Agr. Carussin located in the province of Asti. The farm uses biodynamic farming methods in producing its quality wines.

6. More detailed bioprofiles are available at https://webpages.scu.edu/womenwinemakers/beyond.php

7. Barriques are small barrels normally made of French oak and having a capacity of some 210 L (55 gal).

8. Botti are very large barrels, typically of Slovenian oak, with capacities of over 100,000 L (ca. 26,000 gal).

Notes: Author Bios: Lucia Albino Gilbert, PhD, and John C. (Jack) Gilbert, PhD, both Professors Emeriti, have had long and distinguished careers at The University of Texas at Austin and Santa Clara University and are widely published in their respective fields. Their research on facilitating women's career success in male-dominated scientific fields such as winemaking combines Lucia's academic field of Psychology and John's academic field of Organic Chemistry. They can be reached at [email protected]. Their research website is https://webpages.scu.edu/womenwinemakers/

Content for this article came from our conversations with the winemakers, information they provided us about their wineries and their wine region, and winery websites. Information about the history of the region came from Labor of Love by Suzanne Hoffman (2016), published by Under Discovered Publishing.

The regional map is courtesy of the Guild of Sommeliers, Piemonte, Italy.