Malbec is a grape with a long history throughout the Southwest of France, including Bordeaux where it used to be a big part of the red wine blend. But French Malbec is mostly associated with the town of Cahors where the Romans planted it 2,000 years ago. For centuries it was considered one of the finest wines in the world. When the phylloxera epidemic broke out in the late 1800s most of the 80,000 hectares planted (about 200,000 acres) were ruined. It wasn't until almost a century later that Georges Vigouroux bought Haute-Serre, an abandoned estate, and began replanting the vineyards. Malbec was again growing on a winemaking estate in Cahors!

Grape Collective caught up with Georges' son Bertrand, winemaker of the property, to find out more on the current state of French Malbec, how it fared last Spring in a blind tasting with the best of Bordeaux and why he is grateful for Argentinian Malbec.

(Photo: Georges and Bertrand Vigouroux)

Lisa Denning: You come from a family of winemakers. Did you always think you would be in the business?

Bertrand Gabriel Vigouroux: At the beginning, no. My main interest was to ride horses and I wanted to be a professional, but I also worked with my father at Château Haute-Serre every holiday and in the summer. I loved it and when I was 18, I said to my father, I want to work there, to live in Haute-Serre. And he told me, “if you want to live here, you have to know how to make wine”.

Can you tell me a little bit about the history of Château Haute-Serre?

Château Haute-Serre has a really great history. It was a famous estate. The owners were the family Haute-Serre and they were very influential in the law in the Middle Ages, the 15th century, and they wrote a lot of the laws and they also made wine at Château Haute-Serre and the vineyards existed until phylloxera in 1880. The appellation had disappeared and my father wanted to try and replant it one century after the phylloxera epidemic. It was a lot of work to restart the winery. There were no vineyards, no wine, nothing! It had to be built from scratch. My father started to plant some Malbec again even though Malbec was not popular in the 70s.

Château Haute-Serre has a really great history. It was a famous estate. The owners were the family Haute-Serre and they were very influential in the law in the Middle Ages, the 15th century, and they wrote a lot of the laws and they also made wine at Château Haute-Serre and the vineyards existed until phylloxera in 1880. The appellation had disappeared and my father wanted to try and replant it one century after the phylloxera epidemic. It was a lot of work to restart the winery. There were no vineyards, no wine, nothing! It had to be built from scratch. My father started to plant some Malbec again even though Malbec was not popular in the 70s.

So for a whole century, there was no activity going on there for the most part? Did other people start replanting in the 70s?

It was very difficult. We had two wars and the economy was not so good. After the second war, in 1956, some winegrowers tried to replant the vineyards but the winter of ‘56 was terrible and frost destroyed all the vineyards so they waited 20 more years to begin once again.

Tell me about the terroir in Cahors and your vineyards specifically and why Malbec grows well there.

There are two main terroirs in Cahors: one on limestone, and one on the Kimmeridgian soil. Château Haute-Serre is on the Plateau Calcaire and has a great terroir because the roots grow in the Kimmeridgian soil with red and blue clay and with iron and limestone and we call that in agronomic terms the calcifaire. These elements in the soil make a difference because iron is like an antidote for limestone in the plant. If you have only limestone, your leaves will become yellow. If you want to have green leaves and make a lot of photosynthesis you need to have a lot of iron. It’s the mix between limestone and iron that makes really good terroir with the clay because clay is good for keeping regular water in the plants. It’s like a sponge.

There are two main terroirs in Cahors: one on limestone, and one on the Kimmeridgian soil. Château Haute-Serre is on the Plateau Calcaire and has a great terroir because the roots grow in the Kimmeridgian soil with red and blue clay and with iron and limestone and we call that in agronomic terms the calcifaire. These elements in the soil make a difference because iron is like an antidote for limestone in the plant. If you have only limestone, your leaves will become yellow. If you want to have green leaves and make a lot of photosynthesis you need to have a lot of iron. It’s the mix between limestone and iron that makes really good terroir with the clay because clay is good for keeping regular water in the plants. It’s like a sponge.

And what do you think of the success of Malbec coming from Argentina? Was it a good thing for you?

Yes, when I have an interview and am asked about Argentina I always say thank you to Argentinian winemakers because they make a great wine from Malbec and they show it as good as it could be. The work the Argentinians did for Malbec is amazing. Malbec is now everywhere in the world because Argentinian people opened the market to the world.

In France we’re not in the same situation because we disappeared for one century so we had to rebuild the vineyards from the beginning. I think people like Malbec. You can make a really good wine with it in Argentina or in Cahors. Cahors is the birthplace of Malbec since 2000 years ago and the century of the Malbec was the 19th Century when a lot of Malbec was planted. In Cahors, we had about 80,000 hectares of it then and also in Bordeaux there was a lot of Malbec planted. In the 1855 classification in Bordeaux, the main grape used in the blend was Malbec. Malbec is older than Cabernet Sauvignon.

But Malbec is a diva and it’s not easy to manage it. When the weather’s not so well it’s not easy to work with Malbec and we lose a lot of grapes. You don’t have a regular production every year. Bordeaux forgot about Malbec and focused on Cabernet Sauvignon but Cahors stays with its original grape and we work much more now with planting the Malbec in the right place.

How many hectares of Malbec do you have planted now in Cahors?

More or less, 4,000. We have much more than in the beginning of the 70s when we only had 400. But back in the 1800s, it was 80,000 hectares planted in Cahors. In Mendoza, Argentina it’s 40,000 hectares now.

What other wines do you make besides Malbec?

We started to grow Chardonnay because Kimmeridgian soil is a good soil for Chardonnay and it’s working very well. Albesco is the name of the Chardonnay we produce and it means “I become white”.

And how much of that Chardonnay do you make?

Less than 1,000 cases per year. My total production of all of the wine is around 30,000 cases per year.

I read that Cahors is now a “hotbed of new ideas and avant-garde thinking”. Can you elaborate on that?

I think that now you can drink very good wine in Cahors and we have good ratings with journalists. It’s like an oxymoron cause we are not a new vineyard. We are very old but we also have re-started the vineyards. The people are interested in the wine, of course, but in Cahors you have a wonderful story too. It’s 2000 years old and people like that and it gives a sense of history to a bottle of wine. It’s necessary to have a story.

Tell us about the recent blind tasting that pitted you against some of the top Châteaux in Bordeaux.

When I started to work with my father I would hear, “Oh you make a wine from Cahors, a Malbec wine. Your price is too high. It’s the price of Bordeaux”. That made me very angry because I never understood why I couldn’t put the right price on my bottles. We work just as hard and the wine is just as good as Bordeaux. Because I was Cahors, I needed to have a lower price but then I wouldn’t have the money to do my work as well. I decided to show that Cahors is a really great, exceptional terroir and that we can make wines as good as the best wine in the world. It was my professional challenge to show that we could be back in with the best wines of the world and so we worked hard replanting the vineyards with a high density of plantings to have a good selection of clones and rootstock. And it takes time to do this kind of work. We were then ready for the match.

I said, “Ok we are going to compare in a blind tasting some of the Premier Grand Crus from Bordeaux with our wines and others from our region”. We invited 40 tasters — professionals from everywhere in the world, Canada, US, France, UK. We made a blind tasting and we tasted 10 wines, 5 from Bordeaux and 5 from Occitanie, the new area that is a fusion of Languedoc Roussillon and the Southwest. Chateau Haute-Serre won the tasting with the best ratings from all the tasters. I was very happy because my father started the work in the 1970s because he saw this situation where you have Chateau Haute-Serre next to Chateau Margaux and he was thinking if the wine was so good as in the 19th Century then why couldn’t it be again? And he re-planted the vineyards and after a lot of long work we are again next to the great wines of the world getting the best ratings.

That’s great...congratulations!

Thank you.

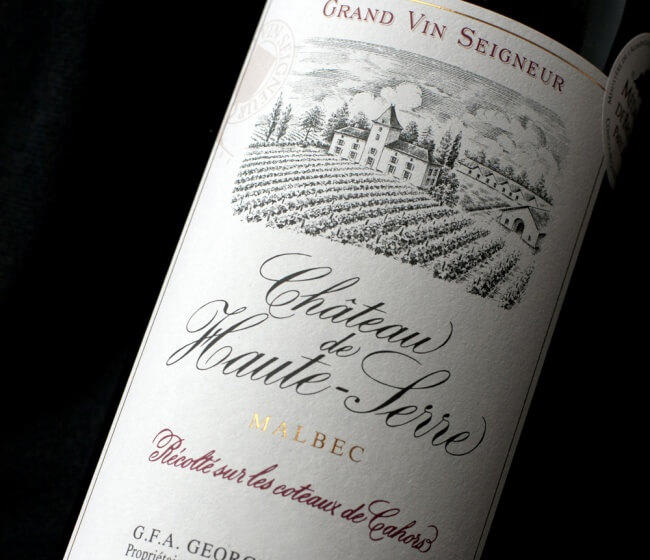

And what about the labeling. Traditionally French labels don’t include the name of the grape but I see that yours do. Can you tell us about that?

And what about the labeling. Traditionally French labels don’t include the name of the grape but I see that yours do. Can you tell us about that?

Yes, I export 70% of my production all over the world and people know my Malbec so the focus was to introduce something new so I put ‘Malbec from Cahors’ on the label. I think before the 1970s knowing about the terroir was very important and people spoke about Bordeaux, Burgundy, Chablis, Sancerre, Cahors and they didn’t speak about the grapes. The new world speaks a lot about grapes and, starting in the 1980s, the focus became on the grapes. Then five or six years ago we are in a new age and people want to know where is the best place in the world for the grape. Where is the best Sauvignon Blanc growing? Is it in Sancerre or in New Zealand? Where are they growing the best Shiraz? Australia or in the Rhone Valley? Where are they growing the best Cabernet Sauvignon, in Napa or in the Medoc?

You also have a new logo on your label.

The new logo has the cross of Occitanie, the new region, on the back of the label by our name and it’s our signature. I put the cross inside a tastevin and it’s the identity of my region with my work.

a tastevin and it’s the identity of my region with my work.

Do you do anything with organics or biodynamics?

We are looking a lot at this kind of thing. We don’t have any label for this process but we expect to in the future because we take care, sometimes much more than organic wines, so we want to have a label for that. My main concern is to give a good product to my consumer and use low sulfites and low pesticides.

How would you sum up your philosophy of winemaking?

My philosophy of winemaking is that I take much more care about the philosophy of the wine than the technical aspects of the wine. I’m a winemaker, but that’s not difficult work to do when you have good terroir. My philosophy is to understand how to make the best grapes in the field. If you understand that, then in the cellar you have nothing to do and you will have good balance in your wine. You'll never have to add anything and it’s perfect in terms of naturality. That’s my philosophy.

I am scientific as well as technical, but my philosophy and what I like the most is to share a moment with people, to take the time to share and the wine is also an invitation to travel. Many, many people who taste my wine say they want to visit the winery. I saw the convergence of wine and traveling. A good region needs to have beautiful wineries and beautiful landscapes with vineyards. I like this philosophy of traveling and wine.

Is there anything else you’d like to tell me that we haven’t discussed?

Just to say, welcome to Cahors!

Thank you! I would love to come visit, speaking of traveling!

You are welcome to come visit us in Cahors. It’s a beautiful city. It’s a Roman city with a strong Middle Ages structure. Cahors is gorgeous.

I heard there’s a beautiful restaurant on your property too.

Yes, that’s right. We have a great chef, one star Michelin. And it’s a very beautiful hotel also for hospitality because we believe wine is just one part of hospitality.

Read more from Lisa Denning on Grape Collective and The Wine Chef.