There’s no doubt about it, retsina is a polarizing wine. Yes, it has its share of fans, but plenty of detractors too. As a traditional Greek wine, retsina is made with the addition of pine resin, which, unsurprisingly, is a turn-off to people who find the uniquely pungent flavor and turpentine-like aromas unappealing. As an interesting side note, while researching this article, I discovered that turpentine is also made from tree resin and that the solvent, a pure one anyways, should smell nice, like pine trees and licorice.

I remember my first time trying retsina decades ago when the wine's quality was iffy at best, and a bottle went for about $3. But, in spite of its rot-gut reputation, I found the signature forest-like scent intriguing and immediately fell for its piney taste. My friend Nicole, on the other hand, took her time warming up to the wine.

“My first experience with retsina was that it tasted like rubbing alcohol or perhaps lighter fluid,” she recalls. “But it became an acquired taste because it paired so well with Greek salads, piled high with feta cheese and stuffed grape leaves.”

Lovers and Haters

Retsina can be a divisive topic within the wine world as well.

There are wine critics who don’t consider retsina to be a wine at all. Mark Squires, whose specialty is Greek wines, is one of them. He wishes the wine would be permanently dropped from the conversation.

“Retsina is wine adulterated with an additive that invariably overwhelms everything else about it, from the grape type to the terroir,” he writes in Retsina: Can We Never Mention It Again? (Robert Parker Wine Review, 1/10/17). Squires says that retsina has harmed the reputation of Greek wine and that it is in Greece's best interest “never to mention retsina in the same sentence as the word ‘wine’ again.”

In the opposite camp is wine writer Eric Asimov who offers hope to retsina lovers like Nicole and me. In Great Retsina, an Oxymoron No More (The New York Times, 1/17/19), he acknowledges that, while inferior retsinas are not going away anytime soon, he believes that the category of wine is slowly undergoing a renaissance.

“Nowadays,” says Asimov, “mass-market retsina, sold in clear 500-milliliter bottles with crown caps, is usually the cheapest wine available in Greece. Often, in cities like Athens, it is mixed with soft drinks and consumed (primarily to catch a buzz) by those on student budgets.”

The renaissance he is talking about has nothing to do with those bottles.

“A trickle of producers,” writes Asimov, “is demonstrating that if retsina is made thoughtfully and carefully, from grapes grown conscientiously, it can be a delicious wine that goes beautifully not only with a wide variety of Greek foods, but with many other assertive cuisines as well. The producers who have embraced retsina are not trying to transform it into a profound wine, a collectible or a bottle worth aging to show its complexities. Instead, they want to turn retsina into a cultural tradition of which modern Greeks can be proud.”

Origins

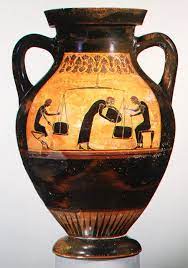

Retsina's history can be traced back to ancient times, when wine was typically stored and transported in clay jugs called amphorae. In Greece, one of the world’s oldest winemaking civilizations, winemakers used thick resin from the abundantly-growing Aleppo pine trees to seal the amphorae and protect the wine from oxidation. Evidence of pine resin has been found in Greek wine vessels dating back to the 13th century B.C.

Retsina's history can be traced back to ancient times, when wine was typically stored and transported in clay jugs called amphorae. In Greece, one of the world’s oldest winemaking civilizations, winemakers used thick resin from the abundantly-growing Aleppo pine trees to seal the amphorae and protect the wine from oxidation. Evidence of pine resin has been found in Greek wine vessels dating back to the 13th century B.C.

Over time, the country's wine drinkers acquired a taste for the distinctive flavor of pine in their wines, and even after wooden barrels became the world’s wine storage vessel of choice, resin continued to be included in Greek wine production.

By the 20th century, however, retsina began to lose its appeal to an increasingly sophisticated Greek population who had been introduced to fruity, non-resinated wines. Many ambitious Greek wine producers abandoned retsina to focus on more marketable, non-resinated wines, made from grapes like Assyrtiko and Xinomavro, which have become extremely successful in the export market. The wineries that continued to make retsina tended to be large, commercial businesses who were more interested in quantity over quality.

Winemaker Dimitris Georgas, owner of Georgas Family, a small winery in Spata of Attica, says that beginning in the 1950s, despite its increasingly poor quality, retsina remained a popular and affordable bulk wine for the working class and it was served "straight from the taverna’s old barrels, filling the five gallon family glass bottles." He noted that as an everyday table wine, there were no quality indicators on the labels either.

Retsina’s Rebirth

In recent years, as Asimov noted, there has been a small group of quality-minded producers that have been championing this distinctly Greek wine. This new generation of innovative winemakers, like Georgas, are using top-notch viticultural and winemaking techniques and are slowly giving retsina a new life.

"The image of retsina today is completely different, because many Greek winemakers have realized that retsina’s quality upgrade is of a great importance for Greek wine," says Stelios Kechris of the award-winning Kechris winery. "Thus we have changed, to a large extent, the image of retsina in the eyes and mind of the contemporary consumer in Greece and internationally. It is now a wine that is perceived as a quality wine, which offers unique opportunities for wine experiences and discoveries."

I was curious to find out what sets these new-style retsinas apart from the mass-market ones. It turns out that the higher-end retsinas are made with carefully grown grapes, a very small amount of the finest resin, and with the use of modern winemaking techniques.

“It’s the grapes we are using,” says Yiannis Paraskevopoulos, founder of Gai'a, one of Greece’s top modern wineries. "We use Roditis grapes that come from vineyards at a high altitude, guaranteeing crispness and fruitiness. Our really nice grapes are turned into wine by state-of-the-art techniques of white winemaking.”

“It’s the grapes we are using,” says Yiannis Paraskevopoulos, founder of Gai'a, one of Greece’s top modern wineries. "We use Roditis grapes that come from vineyards at a high altitude, guaranteeing crispness and fruitiness. Our really nice grapes are turned into wine by state-of-the-art techniques of white winemaking.”

Other wineries prefer to use the Savatiano grape (photo). At Domaine Papagiannakos, located in the Attica region near Athens, the family has been making retsina for three generations from Savatiano, Greece’s most widely planted grape. Stefanos Georgas, export manager of the winery, says that Savatiano is indigenous to Greece and the original variety used in antiquity. Another major factor in the high-quality of Papagiannakos wines, he says, is that the grapes are sourced from older, 50 to 55 year-old vineyards.

Dimitris Georgas is also a fan of the Savatiano variety, despite its bad rap since the 1970s of making thin and flavorless wines. Georgas believes that the grape can provide excellent results when “raised properly.” At Georgas Family, the grapes are meticulously farmed using biodynamic methods, and the vinification is natural with spontaneous fermentation, no interventions and no added sulfites for most wines.

“Retsina is a unique appellation wine with geographical origin,” says Georgas, “and traditionally, the Savatiano grape variety has provided a full body and good balance which are key to supporting the strong pine resin scent. Savatiano is also a fast ripening wine variety, which promotes fresh and yearly retsina in good maturation.”

Yet it's important to note that the law does not dictate which grapes can be used, and producers are free to experiment with other types. Kechris says that the varieties he uses in his family's retsinas are Roditis, Assyrtiko and, for the rosé, Xinomavro.

The Role of Pine Resin

The producers I spoke with agreed that, in addition to carefully vinified grapes, the amount and quality of pine resin plays an important role in how the wine turns out. At Kechris, they aim for a harmonious balance between the aromas from the grapes, the fermentation and the resin.

"The resin we use is collected exclusively from the pine species Pinus Halepensis (Aleppo pine)," explains Kechris. "Resin, as a natural product, has characteristics that depend on many factors ... and are the result of time and harvest method of the resin, in addition to the pine forest's orientation, altitude and proximity to the sea, and also each year’s climate."

Gai'a's Paraskevopoulos says that even though there isn’t an appellation system in place for the pine resin, he says that they “know by experience and tradition that the resin coming from specific forests outperforms others."

“We are using an excellent quality, fresh and non-oxidized pine resin from a very specific pine forest called Kouvaras,” he says. “We use just a fraction of the quantity of resin compared to mass market retsinas. At the end of the day, we are not trying to hide problems that lesser wines have by adding massive amounts of resin. We aim to produce a complex, refreshing white wine, with an herbal twist in it, allowing the fruit to also ‘have a word’ to say.” Paraskevopoulos stresses the importance of using fresh resin since “aged resin oxidizes and conveys to the wine unpleasant aromas, such as paint remover.”

Certain times of the year are better for harvesting the pine resin as well.

“At Domaine Papagiannakos (in photo), we harvest the pine resin, Pinus Halopensis, from Kouvaras at a specific time in the month of June as it has the best quality at that time,” says Stefano Georgas. He says that the winery’s philosophy is to express the Savatiano variety with just a delicate touch of pine resin.

“At Domaine Papagiannakos (in photo), we harvest the pine resin, Pinus Halopensis, from Kouvaras at a specific time in the month of June as it has the best quality at that time,” says Stefano Georgas. He says that the winery’s philosophy is to express the Savatiano variety with just a delicate touch of pine resin.

Over at Georgas Family, the wines see limited resin contact as well. Dimitris Georgas says that for his wines, due to no interventions in the vinification, the pre-fermentation resin is perfectly incorporated into the robust Savatiano grape body.

“The resin is pretty invisible to the mouth,” says Georgas. “Many winemakers are safely exporting retsina around the world and sommeliers are no longer afraid to offer retsina on their menus. Our retsina is very well respected among sommeliers who know how to pair it with certain dishes that result in a beautiful experience for the consumer.”

Food-Friendly Wines

More and more, both the local and export markets are welcoming these relatively mild-tasting retsinas. People who once scorned the wine are now trying this newer style and discovering how well they pair with food.

"Retsina is perfectly suited to the intense aromas of Greek cuisine with herbs and other seasonings and elements like vinegar and garlic," says Kechris. "The acidity of a good retsina cleanses the palate from the greasiness of fried foods, while its aromatic freshness balances the heavy flavor of the olive oil on which Greek cooking is based. The natural brininess of seafood and the saltiness of many preserved foods demand the cool crispness only a good retsina can provide." He recommends pairing the wines with Greek dishes such as small fried fish, grilled lamb chops with rosemary and moussaka with eggplant, but also with Mexican, Indian, Thai and other Asian cuisines.

Paraskevopoulos concurs, saying that there are many ways to enjoy a good, fresh, retsina, especially with recipes that are, as he says, “high-pitched,” and made with bold ingredients like onions, garlic, curry, and “other known wine-killers!"

Paraskevopoulos concurs, saying that there are many ways to enjoy a good, fresh, retsina, especially with recipes that are, as he says, “high-pitched,” and made with bold ingredients like onions, garlic, curry, and “other known wine-killers!"

“Retsina acts as a small herbal bomb,” he says, “refreshing your palate and renewing your experience with what you are eating. Retsina has the power to set an honest fight with those wine destroyers and get out of it victoriously, for the benefit of us all.”

Night at the Taverna

Curious to test out some of these new style retsinas, I met Nicole for dinner at Snack Taverna, a superb, casual Greek restaurant in Manhattan's West Village. We tried several wines alongside delicious and fresh-flavored dishes, including an assortment of pungent Greek dips (tzatziki, hummus, taramasalata, and more), garlicky shrimp with barrel-aged feta, and tender braised lamb shank with cinnamon scented tomatoes, kalamata olives and graviera cheese.

One sip of the Gai'a Ritinitis Nobilis took me back in time and reminded me of why I love retsina. Of the wines we tasted, this one had the strongest notes of pine, but it wasn’t overpowering at all. Due to its balanced notes of fruit, pine and citrusy acidity, the wine went perfectly with the creamy, full-flavored Greek spreads. It's no wonder this wine is a permanent part of Snack Taverna's mostly-Greek wine menu.

The Papagiannakos Retsina, on the other hand, had the least prominent pine resin aromas and could've almost passed for a non-resinated wine if tasted blind. But it was delicious—refined and elegant—with nice acidity and notes of pear and lemon, and with just a mere hint of the piney taste on the mid-palate.

The Georgas Family Black Label, unfined, unfiltered and without added sulfites, was our favorite of the evening. It was the most complex—from its extended lees aging— and full of bright citrus and fruit notes, along with the perfect amount of pine resin flavor and a superb tannic structure. Upon opening, the slight effervescence refreshed our taste buds, while an ash-like, chalky finish gave it an extra bit of interest. Over the course of the meal, there were many exciting layers of flavors in the Georgas wine that developed and changed, much to our enjoyment.

The Georgas Family Black Label, unfined, unfiltered and without added sulfites, was our favorite of the evening. It was the most complex—from its extended lees aging— and full of bright citrus and fruit notes, along with the perfect amount of pine resin flavor and a superb tannic structure. Upon opening, the slight effervescence refreshed our taste buds, while an ash-like, chalky finish gave it an extra bit of interest. Over the course of the meal, there were many exciting layers of flavors in the Georgas wine that developed and changed, much to our enjoyment.

We also enjoyed the Georgas Family Traditional Retsina, made with a touch of sulfites at bottling. At first, its bitterness was a bit too prominent but, over time, it lessened and the fruit and pine flavors became more noticeable. The wine was particularly tasty when paired with food.

Unfortunately, I didn’t receive a sample of Kechris’ top retsina wine, Tear of The Pine, in time for the dinner, but I remember tasting it a few years ago and loving its refined and delicate take on the retsina wines of yore.

These interesting wines, bound to tradition but not trapped in time, give proof that, when made with care, retsina is capable of reaching new heights. They are food-friendly wines that deserve to be celebrated and enjoyed at the table.