The Ventisquero winery was founded in 2000 in the Maipo Valley. Ventisquero currently has seven vineyards in the major growing regions throughout Chile. The diversity of climates allows Ventisquero to produce a variety of wines each with a unique expression of Chile’s distinct terroirs. In 2004 Ventisquero and Tosso partnered with former Penfolds winemaker John Duval to develop the Pangea Syrah range from the Apalta region.

Grape Collective talks to winemaker Felipe Tosso, who has been with the estate since its inception.

Christopher Barnes: Felipe, tell us about Ventisquero.

Felipe Tosso: Our first vintage was 2001. We planted a little bit earlier. We started in 1996 with the project. It’s owned by Gonzalo Vial. Just one owner. Private owner. We have several vineyards planted from Casablanca, Leyda, in the Maipo Valley, and here in Apalta, where we are right now.

What is the philosophy of winemaking at Ventisquero?

What is the philosophy of winemaking at Ventisquero?

I would say that we only grow our own grapes today. One of the things I say is, “We are terroir-driven wines.” That means there is a lot of common sense in the wine, not too much winemaking, really. We try to let the grapes express in the glass. Not a lot of filtration, or no filtration sometimes, depending on the level of the wine. Really concentrating on getting a more gastronomic experience with the wine, so all the winemakers work together. We work with our partner John Duval, our wine consultant, and some of our partners, on making wines that you can drink with food.

Because of that, we don’t do super big wines. We’re much more focused on elegance. On nice tannins. On complexity in the wines. Earthiness. We like to take out the flavors of the earth. Sometimes our wines are not perfect. They’re not polished, exactly, but they’re nice to have with food. That’s a very important part of the way we make wine.

John Duval, he was the head winemaker at Penfolds for many years. I’m assuming he’s making Syrah here.

The one that we have right now is a blend of Grenache, Carignan, and Mourvèdre. In Spanish we say, “Garnacha, Cadinena, y Mataró.” We do Carménère together also. We do a blend of Carménère and Syrah. We do, of course, a straight Syrah. Here in Chile it’s Syrah, in Australia it would be Shiraz. So we do Syrah in Chile, not Shiraz. But he’s a red winemaker mainly.

How did John Duval adapt to Chilean terroir as somebody who has been making wine for so many years in a very, very specific place?

I think you have such a talented winemaker. The first thing is that John is not bringing a recipe. The first thing he will tell you with his words will be, “I don’t bring a recipe to Chile.” The first is trying to understand Chile. Working together. Using our Chilean winemaking methods, and of course learning from him. We’ve been working nearly 12 years together. It’s a long time. I go to Australia and he comes here.

Just to put it in perspective, John has never, ever made a cold maceration. We always do cold maceration. He doesn’t need it; we like it. He doesn’t do very long skin-contacts in Australia; we do from three weeks up to six weeks of skin-contacts. There are a lot of differences, but it’s like cooking to me. To me, to be a winemaker is very near to being a cook. There’s a way that you like to eat, and that system together ... we connect very well together. We like food; we cook together, and then the winemaking is about having nice tannins. Having elegant wines. Structured wines that are firm, but are also beautiful aromatically. There’s a philosophy of winemaking that we have that is very similar. In a certain way I chose him as a consultant winemaker, and he chose us, saying, “Okay, I’ll work with you guys. You have something I would like to work with. I think it is something exciting.” We try to make exciting wines.

Felipe, tell us about your background. How did you get involved in wine, and what was that “ah-ha” moment when you knew that you were going to be a slave to the grape?

Look, I was very good at math, which has nothing to do with winemaking. I said I was going to be a civil engineer like my dad. Then I had the luck to live in Davis when I was very small, from five to 10 years old. Beautiful sky. The fields were nearby; it was a countryside area.

When we came back to Chile, I was 10 years old. I thought, “There is a little more smog in Santiago. A little more pollution. I don’t want to live in Santiago.” Then I went to university. After two years of studying civil engineering I said, “I’ll have to work in buildings, offices. I want to live in the countryside.” So I changed my career to study agronomical science. Once inside this field of study I discovered winemaking. I found it fascinating. I went to some tasting classes. Before, I always wanted to do that. A little bit of the artistic part. A little bit of the sensory part. You can feel things. But it also has a lot of science.

Today, I use the science aspect of it when we have problems, but to me winemaking really involves a lot of intuition. It’s a lot like painting. There’s a science to painting. There’s a technique. But when you get freedom from that - the technique - you just go for it. That’s how I feel after 21 years of making wine.

I have had been lucky to travel a lot, so I had a lot of work before in Concha Y Toro. Beautiful winery there. I learned a lot there and made good friends. Then I went to a smaller winery, though we have been growing bigger over last 15 years. But, I love the countryside way of life. The connection to the land and to the earth, to be able to see the sky like today that is always blue and no pollution, a little bit of wind - that’s what connects me to winemaking.

Felipe, how many different varietals do you work with right now?

We work with 12 different varietals. But mainly five reds and two whites. But the main thing is Cabernet and Carménère. Also Pinot Noir is getting very important, and so is Syrah. Those two, Pinot Noir is maybe second. We also have Merlot of course. Then we have a little bit of Petit Verdot, Cabernet Franc, and some other varieties that we are trying. We’ve had a little bit of Sangiovese, things like that. But the main thing would be Cabernet, Carménère, and then the second choice would be Pinot Noir and Syrah.

But of course in this area there are some Mediterranean varieties that we have planted recently, about five years ago. We have some Grenache, some Carignan, and some Mourvèdre. Spanish varieties that are used a lot in the south of France and in Spain. With the weather here it works very, very well, especially here on these hillsides. That’s mainly on the reds. As for white wines, I would say we are very classic, so Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay are the main varieties. We have a little bit of Pinot Gris, a little bit of Viognier, some interesting things. But mainly Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc.

Sauvignon Blanc is big in this country today. I would say that after Cabernet Sauvignon and Carménère, our third most sold variety is Sauvignon Blanc.

Ventisquero's Apalta vineyards

How has your viticulture and winemaking changed in the time that you’ve been making wine here?

I think it hasn’t changed a lot. I think we were lucky to plant in 1998, when there was a lot of expertise and research going on. There were a lot of studies of terroir. Then maybe 10 years later, or eight years later, we did a big study about soils.

Today, after years of planting, the things that didn’t work we’re changing. We’re rethinking. For some things we’re using some very good new clones. Everything that we do we trial first, so we plant half a hectare, and we see after four or five years if it works. Or we go and see our neighbor who has something good. We don’t plant just because it’s in fashion. It takes time. After 17 years we have been rethinking. We had a hillside where we had some Merlot; but it was too warm for Merlot. Merlot doesn’t like so much heat. We already planted another part of it with a little bit of Grenache. It’s similar soil so we’re going to plant a little bit more Grenache.

So in general, like this farm that was a little bit more Cabernet-driven, today it is becoming a more Mediterranean style of vineyard for red wines. A little bit more Grenache. Syrah is very important. Some Carménère is important. I think we are rethinking some things that we have done before.

In terms of the Chilean wine industry, what do you see as some of the challenges that it’s facing right now?

I think one of the big challenges is to be able to show people we are well-known to be producers of good value wines, but we are more than that. I think people need to appreciate that there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on from our old vines to new plantings, to more extreme areas. We need to show people the diversity of Chile. From the north to the south, from the coast to the Andes mountains, there are a lot of small things happening.

Normally we see the big mass production type of things that people are able to get. How do we show the small producers of wine who are much more interesting than the massive wine producers? I think that’s a big challenge today. We talk about industry, but this is not really an industry. How do we show that we’re real farmers? There are people on the back of our wine, not factories of wine, really. I think that’s the way to show Chile, more and more. Do you see this? You don’t see any factory. There’s no noise. Just some birds. This is what we work on. Making real wine. I think that’s the other side we have to show.

You will be soon in the south of Chile, and you will see the real people picking things for us. You will see people picking grapes. The real workers are real Chilean people. They have small pieces of our vineyards. I think the modern part with the old part, but small productions of good wines with character. Not just a commodity. I think that’s the next step for Chile.

Some people talk about Carménère as the grape of Chile, and some people talk about Cabernet. Do you feel that Chile should stand behind one grape, or do you feel that Chile should represent multiple varietals?

I think the most important variety in Chile is Cabernet Sauvignon, but it is not unique. We have to keep doing it well, because people like to drink Cabernet Sauvignon. It is a challenge to make Cabernet Sauvignon outside from all over the world, also from Chile. But there’s some beautiful Cabernet Sauvignon also from Chile. Amazing. To just be focused on one variety - to me as a winemaker - I think is boring. I love to do different things. Maybe if you’re in an area just devoted to Cabernet Sauvignon, maybe you will be more focused and do it better, but I love the diversity here. One day I can do a Carménère that I harvest in the last days of April. Then I can harvest Pinot Noir in the middle of March in the cooler area.

We have to be more original. From some areas, these are the best varieties. In all the important wine countries in Europe you don’t see just one variety. In the north of Italy you cannot do what you do in the south of Italy. It’s completely different. Chile is a little like that also. So the diversity will come more and more. Today, I think we are maybe too concentrated on Cabernet Sauvignon. There’s Carménère, but I don’t think it will ever be, “This is our flagship.” Of course it’s unique from us, but I think we are still quite a young country in terms of our activity now. We’re an old wine country with 500 years of history, and we are recuperating some of our old stuff. I think that part is fascinating, but there’s also new stuff coming.

All that diversity makes it interesting. Maybe it’s not so easy to communicate outside, but it’s what’s happening right now. A lot of things are happening. Some people planted a little bit of Riesling on the mountain. Amazing. There’s only one guy. One day maybe you’ll have 20 guys doing that. Diversity is the thing about Chile. Chile is a very diverse country with its mountains, hillsides, flat areas, rivers, and coastal areas. That diversity of soils and terroirs make it a diverse area to plant different things.

One of the challenges with wine in Chile, in terms of the international perception, is that a lot of inexpensive, low quality, value wines were sold in Chile in the ‘90s. People began to associate Chile with that type of wine. How does Chile change the perception internationally, and show people the interesting things it’s doing, and the different climates and wines that are coming out of these different areas?

It’s a thing that nobody has the magic answer to, because that’s what I have been talking about for the last 20 years. The only thing to do is at least travel the world and show what you’re doing. I think sommeliers today are key. People who know: journalists, media. Go to everything. I think there is a world of that.

But that is also happening for a lot of other countries. You see Spain doing that, you see a lot of other countries. It is important that Chile keeps doing good value wines, because that’s what sells on the normal shelf at the supermarket, but there’s a lot of need to promote the small growers. To have the knowledge is very important to be important to your country. Our people drink more Chilean wines in more quantity, in more diversity. Not just the classic ones.

How do you get that word out?

Today, as winemakers, we’re not just hard workers in the winery anymore. We’re communicators. To communicate is a thing that is a must today for us. If you want to go outside, you have to speak English. You have to go outside. You have to know the people; you have to know the journalists; you have to know the media; you have to know the sommeliers; you have to go to restaurants. You have to get outside.

To me, wine is about people. When I go to buy wine in a wine shop, I ask the guy, “Which wine do I buy? Tell me the story of that wine.” I buy wines with a story on the back as often as I can. To me it represents a way like a painter, like a movie, like a singer. When you go to a winery, it’s not just the packaging. It’s why do they do the wines in that way? There’s a story on the back.

It’s not so easy with just a label. We try to show things with a label, but sometimes the label doesn’t say who you really are. But when that doesn’t happen, you have to go outside and show your wines and show what’s happening. It takes time. You have to know it will take maybe the rest of your life to change that.

I like to do good wines, and I like to go outside and communicate. I spend like three months traveling just to communicate, and I think a lot of my partners do the same. It’s the only way. Get out there. Bring more people. Go there.

In vintage time, I receive two twice a week. People from all over the world. I tell them, “Bring them in vintage.” They come and work with me. I say, “I go to Apalta, I have to go and taste the grapes.” They come and taste the grapes with me. I go to the winery; they ferment with me. They are part of my work, so I consider it still work, but they understand what we’re doing.

It’s the only way: show, show, show. The more Chileans travel outside, the more Chileans show our wine, the more partners we have in other parts - in China, in the States, in Canada and Brazil, wherever – the more people would love Chilean wine.

Tell us about the terroir in Apalta.

Well if you just see how dramatic these hillsides are, and we have terraces and a big mountain over there, and a place where we have very old vineyards - downstairs there are some growers, they have some vineyards that are over a hundred years old, plus these here are new vineyards in the hillsides. When you see the colors of a vineyard, and the soils, that shows you that you have different soils. A lot of soils that sometimes just in 10 feet change completely.

It makes it very challenging as to which varieties are in what place, but because of the hillsides, not all the hills are good for planting. That’s one thing. Everybody says, “Oh, all these hills are amazing.” No, not all the hills are good. The hills that are good have a beautiful thing. First they restrain the vineyard so the vineyard grows slowly. They have good drainage. Chile has very good granite. There’s a lot of quartz and iron, and some red clays that are very interesting.

The red clays and granite here, and a lot of stones and gravel, make it a very interesting soil, because you can have a little bit of clay that gives a little bit of power to the wine. But you also have the minerality of the granite, and that makes this a very beautiful area. But it’s not a cool area, it’s a warmer area. You really have to have red grapes. You need varieties that love sun. I think that’s the beauty of Apalta.

Ventisquero, Sector La Isla S/N, Lote A, Lo Miranda, Doñihue, Chile, Tel.: +56 (72) 244 4300, Email: [email protected], www.ventisquero.com, @vventisquero

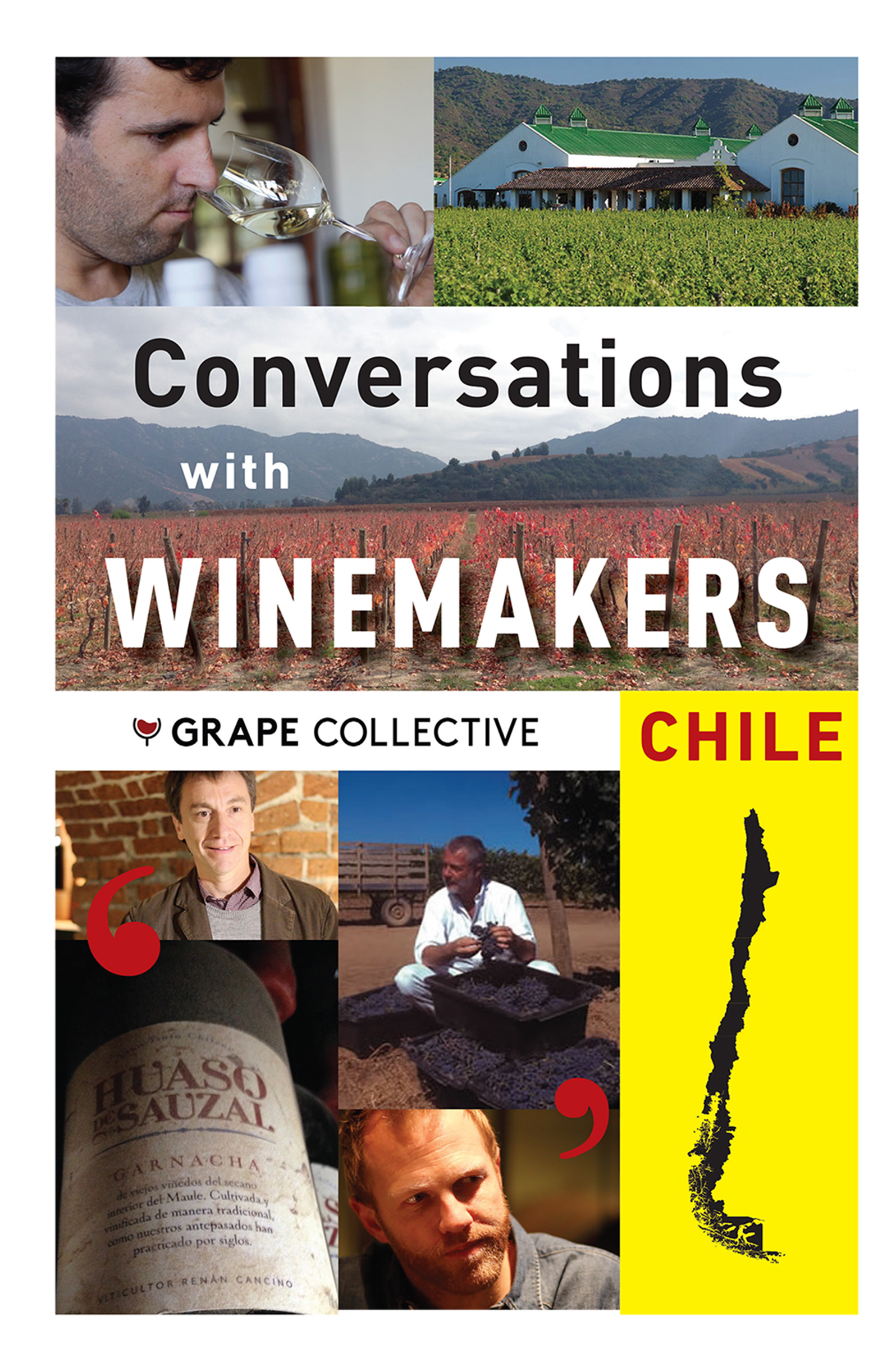

Check out our new eBook on the new wave of artisan Chilean winemakers, Conversations with Winemakers: Chile on Amazon for $3.99.

Check out our interview with Ventisquero consulting winemaker, former Penfolds head John Duval