"Healthy things can only grow in healthy surroundings" is what Thomas Niedermayr’s father Rudolf taught him at a very young age. It was the 1980s and manmade products to fight off insects and plant diseases were now widespread. Agriculture had become much easier and more profitable, and most farmers viewed organic cultivation as a backward way of growing crops.

But the use of synthetic chemicals did not sit well with Rudolf Niedermayr. As a wine grower in Alto Adige, a strikingly beautiful region on the Italian side of the Alps, Niedermayr wanted to work with nature, not bully it. A visionary, he could see how the repeated use of powerful insecticides and fertilizers would destroy the environment. By the mid-1980s he had switched to organic viticulture and his vineyards thrived under his care for decades.

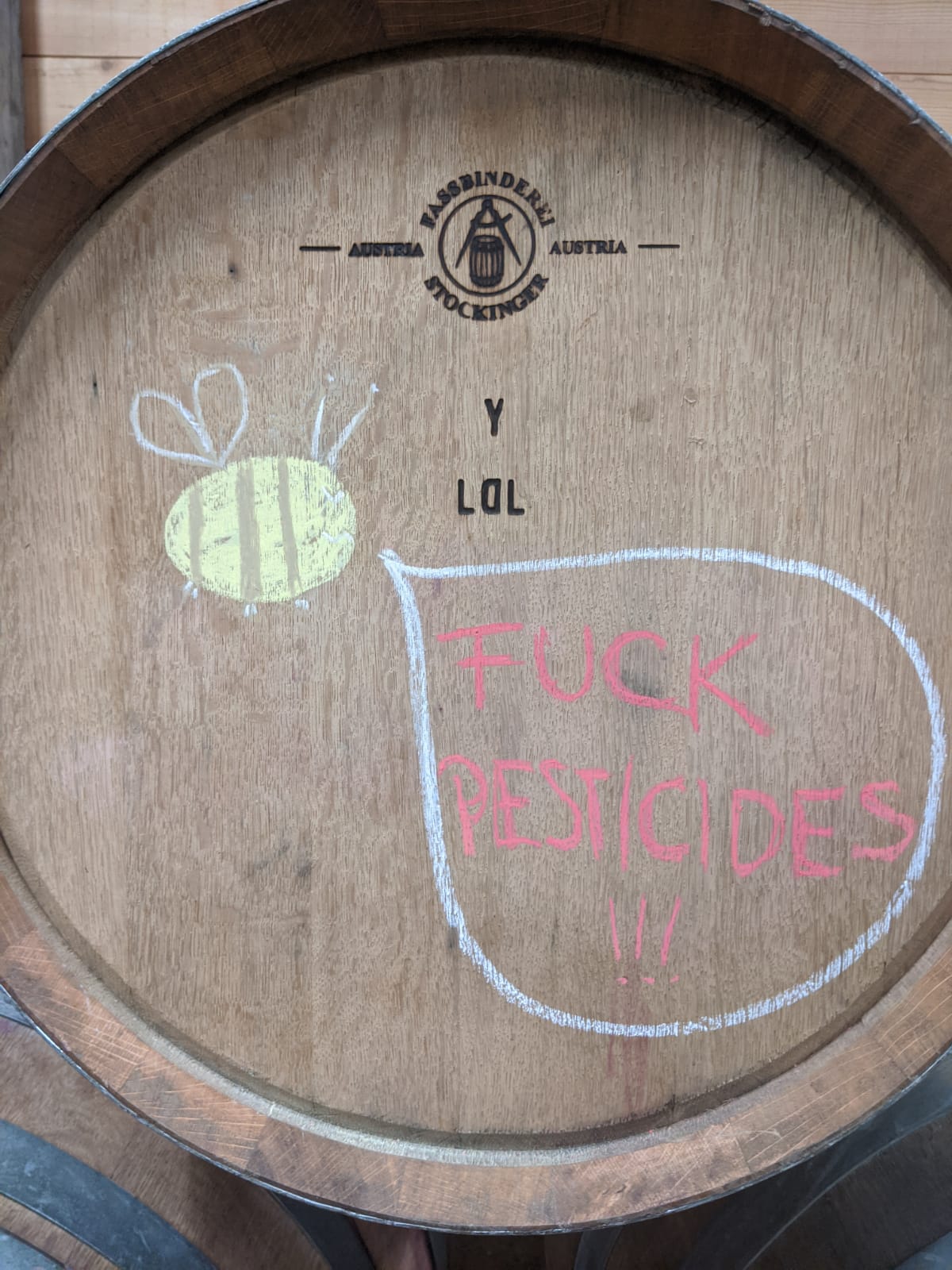

Since 2012, Thomas Niedermayr has taken his father’s baton and run with it. At Thomas Niedermayr Hof Gandberg winery, the whole winemaking process—from grape to bottle—unfolds in the most natural way. Niedermayr has eliminated the need for sprays, even organically-allowed copper and sulphur, by planting fungus-resistant ‘PIWI’ grape varieties. The vineyards are teeming with biodiversity; there are a multitude of fruit and vegetable crops, as well as livestock, bees, spiders, and snakes. In the cellar, the natural process continues: fermentation occurs solely with the use of native yeasts, and the wines are unfiltered and unfined.

Two of the three Thomas Niedermayr wines I sampled are made from grapes that were unfamiliar to me: Bronner and Solaris, born from a crossing of mostly European and North American varieties. The third wine, ‘Sonnrain,’ is a blend of Solaris, Muscaris & Traminer. All three express vibrant energy and striking freshness. And, while the fruit notes—tropical, citrus and stone—are present, the wines lean in a more savory direction, with remarkable mineral, vegetal and herbal notes.

I caught up with Thomas Niedermayr in March by email to find out more about how he makes deliciously imperfect and charismatic wines.

Your father was a visionary winemaker of Alto Adige. Can you tell us more about him and the

history of the winery, including how it got its name, Hof Gandberg? Our winery lies at the foot of the “Gandberg”, a mountain that rises 800 meters high. The “Gandberg” is our house mountain, as we call it in South Tyrol. My father was a visionary, yes, as he comes from a time (1960s to 80s) where very toxic synthetical-chemical pesticides were the norm. He always was environmentally-conscious and felt connected to nature so the whole system didn’t make sense to him and he felt that this was not the way to build a (better) future. In the 80s, he joined environmental groups and it became clear to him that he wanted to work in a healthy way, produce high quality foods and work in a way that does not exploit nature but preserves and gives back. He eventually found his way to organic agriculture which was very new and unknown to most people. Organically produce foods were not valued back then, so they had to find their own ways to market. This meant that my father was part of the founding of an organic apple co-operative and he first made wine from his own grapes in 1993.

Our winery lies at the foot of the “Gandberg”, a mountain that rises 800 meters high. The “Gandberg” is our house mountain, as we call it in South Tyrol. My father was a visionary, yes, as he comes from a time (1960s to 80s) where very toxic synthetical-chemical pesticides were the norm. He always was environmentally-conscious and felt connected to nature so the whole system didn’t make sense to him and he felt that this was not the way to build a (better) future. In the 80s, he joined environmental groups and it became clear to him that he wanted to work in a healthy way, produce high quality foods and work in a way that does not exploit nature but preserves and gives back. He eventually found his way to organic agriculture which was very new and unknown to most people. Organically produce foods were not valued back then, so they had to find their own ways to market. This meant that my father was part of the founding of an organic apple co-operative and he first made wine from his own grapes in 1993.

In 2012, I took over the winery and since then we have evolved and are evolving constantly. I put the focus on the wines and their unique character. My father made wines in a more “classic” way and I make wines that focus on the depth, complexity, characteristics of each year and varieties. That includes fermentation with vineyard-own yeasts, no fining or filtration and a minimal use of sulfur.

Growing up, did you always think you would be a part of the wine business or did you ever want to do something else?

After middle school, I did my apprenticeship as a carpenter and worked in this job for approximately 10 years! I have five siblings and none of us initially thought about taking over the winery. I grew in it and step by step was fascinated more and more by the process of grapes becoming wine and working with nature. But in my heart, I am still a craftsman, an agricultural craftsman. Before I took over the winery, I completed a professional school for wine and worked abroad. Only when I had an idea of how I wanted to lead the winery was when I decided to come back and take over.

Your winery is located in Alto Adige, within the larger Trentino-Alto Adige wine appellation. Can you tell us a little bit more about your land in terms of its natural environment?

In South Tyrol we are surrounded by mountains, right behind the farm there are mountains up to 1800 meters high. There are mixed forests and of course a lot of cultivated areas with wine and apples. In Eppan, where we live and work, we are in the heart of the largest wine growing area of South Tyrol. In our vicinity, we have several lakes and it is a historical area with castles and palaces. Our climate is strongly influenced by the mediterranean climate since the main valley is open to the south. Nevertheless, it gets cold in autumn and winter because we are also influenced by the alpine climate. Historically, our region is known for cultivating wine, apples, apricots, pears and plums.

Most of the winemaking culture of Trentino-Alto Adige is centered on co-operatives. Why is that and how is it to be an independent winemaker in the region?

The co-operatives have a long tradition. It dates back to times of crisis, around the end of the 19th century. In this region, a lot of farms are small, the average grape farmer has less than one hectare. With forming co-operatives, they were able to join forces, especially when it comes to vinification and marketing of the wines.

In the early 90s, the “independent winemakers (vignerons) of South Tyrol” formed and they have been the rebels, outlaws and seen almost as extremists. But that step was important, also to build a healthy competition that motivates, and the quality level of the wine all over the South Tyrol has risen. Today these independent winemakers make up 7% and all winegrowers have become closer again. We have a good exchange of knowledge and information and come together as a community.

You make wines, known as PIWI, from fungus-resistant grape varieties. What does PIWI stand for and can you tell us more? Piwi is short for “pilzwiderstandsfähig” in German and simply means fungus resistant. We’ve been working with fungus resistant varieties for almost 30 years. The name “Piwi” was given when farmers built an organization that focuses on growing these varieties and exchanging knowledge on how to farm, which varieties to plant, and to learn about new varieties. The research into resistant grape varieties started over 250 years ago, but this was just in wine. It is a natural process to select plants that are better and stronger and cultivate them. Farmers have done that for thousands of years. It is about finding varieties that are robust and able to survive without massive use of pesticides which have climate changing impact.

Piwi is short for “pilzwiderstandsfähig” in German and simply means fungus resistant. We’ve been working with fungus resistant varieties for almost 30 years. The name “Piwi” was given when farmers built an organization that focuses on growing these varieties and exchanging knowledge on how to farm, which varieties to plant, and to learn about new varieties. The research into resistant grape varieties started over 250 years ago, but this was just in wine. It is a natural process to select plants that are better and stronger and cultivate them. Farmers have done that for thousands of years. It is about finding varieties that are robust and able to survive without massive use of pesticides which have climate changing impact.

Piwis bring many advantages, like a soil that is not compressed due to heavy use of machine work. They give us the answer to many questions and problems we have in today’s wine growing. We are able to harvest healthy, high quality grapes and make elegant, complex and long-living wines.

What is your philosophy of winemaking?

My goal is to produce elegant, distinct and complex wines that are of high value. This is the challenge and what I strive for. My philosophy is to intervene as little as possible and give the wines my patience, to give each of them the time they need. I am very careful with my wines; I fully expose the must to oxidation but work in a reductive way when must becomes wine. I leave them on the lees for a long time and our cellar is very purist and clean, to make working there easy and practical and also reduce the wines’ exposure to microbes.

What does being a natural winemaker mean to you?

For me it means to strive for the highest quality, always having the full cycle in mind. Everything has to work together, from growing vines to cellar work, the craftsmanship and your senses. Natural wine is an expression of the interplay of humans and nature. We see that great things arise when the parameters are balanced. Natural wine is a stretchable word, like sustainability. The human aspect plays a big role, as well as the quality of life and work. For me it is important to see the holistic context about natural wine and not focus solely on whether it is unfined and unfiltered.

Another aspect of being a natural winemaker is the great community we have. I have been able to build friendships beyond wine since it is not just about wine but about how your thought processes are, how you view and live agriculture. You meet like-minded people, feel understood and you have the same visions and ideals. We exchange information and values on a great level and evolve together.

Have you ever thought about planting more marketable varieties like Chardonnay or Sauvignon Blanc?

Never! It would be like asking “Do you want to drink wines that make sure that our soil, environment and ground water is full of pesticides as well as finding these pesticides in your glass of wine at the end?” And if if you said yes, we would have to go different ways.

There are a lot of different Piwi varieties and the challenge is to find the ones that are suitable for the soil, location and climate. Our wine surely has edges and corners, but not for the fact that it is made from Piwi but because they are handcrafted wines that speak of where they come from. We face the responsibility we have: a respect of nature, our fellow humans and the ones that will come after us. The current market-system is too short-term. Of course, I would make more profit with planting Chardonnay but what will last at the end? The way we capitalize today has no future.

Let’s talk about biodiversity. Why is it so important to you? What else lives on and grows on your land besides grapes?

Let’s talk about biodiversity. Why is it so important to you? What else lives on and grows on your land besides grapes?

Grapes are our main culture, but we have apples too. Both are permanent cultures that stay for years and decades. To break up this monosystem we are working towards regenerative agriculture. That means we are binding a lot of carbon in our soil, which is essential to protect our climate. We have a lively, healthy soil today after working for decades with resistant varieties, minimizing the number of times we have to drive in the vineyards in general, and not using fertilizer for over 30 years now. This also leads to a better nutrient cycle where the vines are able to absorb nutrients and minerals better. Between our vines we grow grains like spelt or emmer, and also corn, potatoes, and pumpkins. Alternate rows stay covered with plants like leguminosae, wild plants and all kinds of flowering crops.

The bloom range is so important for insects that are attracted by pollen and nectar. The more biodiversity we have in flora and fauna, the more a natural balance prevails without us humans having to intervene. You can feel that a vineyard is part of nature when go through the rows or work with the wines and you hear all the buzzing and bugs, butterflies, bumblebees and bees flying around you. It is something that we humans can feel.

Your winery is a member of the Bioland association. Can you tell us about this organization?

Bioland is our organic association which was founded 50 years ago in Germany. My father was one of the founding members of Bioland here in South Tyrol. It was important back then for the farmers to have a platform to exchange information and knowledge, to have people to talk to and ask questions and learn together from shared experiences. It is still important for those reasons today and beyond. Bioland does valuable work since it not only cares about us farmers but works on change on a political level, participates in agricultural politics. This is so important, since we can only change so much as farmers. Additionally, Bioland is working towards stricter rules in organic agriculture in Europe which are necessary. Bioland South Tyrol has over 1,000 members today and we are proud of it!

What types of vessels do you use to age your wines?

What types of vessels do you use to age your wines?

We use wood and steel. Our wooden barrels are usually between 500 and 1000 liters and we focus on neutral and/or used wooden barrels.

How many bottles of wine do you make each year and what percentage are exported?

We produce 40,000 bottles each year. Most of our wines are shipped nationally here in Italy. This dynamic changed recently, also due to the Coronavirus when Italy was so restricted. We are represented in several other countries today, mostly in restaurants and specialized shops. We see a strong evolution in export but it is changing a lot these days.

What do you enjoy most about being a winemaker?

The community of people with the same visions and ideals, people who value food and drinks and how they are made. Also the diversity of work, especially on a small farm like we are, every day brings a new adventure. One of the most exciting parts of a year for me is harvest, we work all year towards it and these days are so crucial and you set in stone what should happen with the wines. Accompanying the wines and watching their evolution is fascinating to me.

What do you find the most challenging?

Maybe the bureaucracy! It is getting to be more and more. The marketing is a challenge too, we work in a very competitive market and wine consumption is regressing in most countries. To find my place is a challenge.

Which regional dishes do you pair with your wines?

A go to is our traditional board with speck, regional cheeses, antipasti and fresh bread. It is quick to make and I think easy to pair with all of our wines. Then schluzer, which are a bit like Ravioli and we make them with spinach or pumpkin filling for example. Different kinds of knödel (dumplings) with cheese, spinach, beetroot or other goods of the season. We eat very seasonally, make our own pasta and bread from the grains in our vineyards and eat a lot of vegetables and fruit that grow on the farm. Something great we discovered last year is pesto out of our young vines’ shoots! With freshly made pasta, it is heaven. We rarely eat meat and if we do, it is rabbit or rooster that grew up next to us.

Outside of Alto Adige, what are some of your favorite wines?

I adore my Slovenian colleagues which work with lots with skin contact wines, like Klinec. I have a lot of good colleagues from Austria—I am fascinated by Sepp Muster, Andreas Tscheppe and many more. I also enjoy wines from France, from the Jura where I am fond of their acidity and freshness. I don’t have one favorite, for me it is a lot about what ideas, which philosophy, which characters stand behind the wines. I just got to meet Ronald of Winzerhof Linder winery in Germany and I am enthusiastic about his wines, his approach of putting permaculture and probiotic plant protection first—very unconventional methods, but they work. He is also working to be free of the pesticide-industry, which is our goal with Piwis too. We want to be as free as a farm can be.