You’re never too old to play with your food. Media and José treated us to a feast a few months ago that called for Mexican oregano. The leftover stems looked hearty, so Dottie, who has been growing herbs for years, rooted it and now we cook with it, too. Its citrusy pungency is nothing like the Italian oregano we grew up with so it’s fun to experiment by adding it to different dishes to taste what happens.

Wine can be fun, too. There’s no One Way to enjoy it. Different strokes for different folks. We owe the good folks at Gundlach Bundschu Winery in Sonoma County and a special grape for reminding us about all of this. The nudge came in a couple bottles of 2019 Gundlach Bundschu Dry Gewürztraminer that delivered two different and engaging experiences. They were like watching the same Broadway drama but with alternate endings.

Here’s the story. We’ve been fans of Gewürztraminer for a long time. At its best, it has a nose of white pepper, roses and lychee and a lingering taste of spice that’s unlike any other white. Alsace is the home of great Gewürztraminer (ge-vertz-tra-mee-ner), but we’ve also had outstanding ones from Germany, Australia and elsewhere. Over the years, though, it seems most Gewürz that’s supposedly dry is sweet. While intentionally sweet Gewürz can be a treat, when we want dry Gewürz, what we’re longing for is the wonderfully fleshy, high acid, complex versions that pop in our mouths.

When people talk about outstanding Gewürz from California, you’re likely to hear the names of two family-owned wineries: Navarro Vineyards and Winery in the Anderson Valley in Mendocino and Gundlach Bundschu. We consider Navarro’s Dry Gewürz a unicorn wine and we do our happy dance when we find it. We’ve been fans of Gundlach Bundschu for so long that, more than 20 years ago, we visited the winery, bought a bottle of its Kleinberger (which it doesn’t make anymore) and had a picnic with it right there.

(Photo: Jeff Bundschu, president of Gundlach Bundschu Winery, the oldest family-owned winery in California, and a sixth generation winemaker. The year on his hat, 1858, is the year Jacob Gundlach purchased land in Sonoma for his vineyards)

We had had other wines from GunBun, as people call it, but had not recently had its Gewürz until pioneering winemaker David Ramey of Ramey Wine Cellars wrote a couple of years ago that if we loved the Navarro, we had to try the GunBun. The Bundschus read that and sent us the 2018 Gewürz, which we seriously enjoyed with whole, roasted Branzino. We noted the wine’s “spicy, dry, white-pepper prickliness.”

A few weeks ago, the winery sent us two bottles of the 2019, which costs $25. We opened the first with great anticipation and it was … good. We wrote: “Nice nose of lychee and white pepper but no bing on the nose. Taste is pleasant, but lacks intensity, just doesn’t taste like it’s bursting with fruit. Not sweet but not really fleshy. Later, Dottie gets white peach and pepper. Now it’s so much better. Dottie says we should have decanted.” To be fair, Dottie has been frequently suggesting of late that we decant, so often in fact that it’s become sort of a joke between us.

Hmmmmm. Good thing we had a second bottle. We waited a week. This time, Dottie made pork roast, which we consider a classic pairing with Gewürztraminer. The decanter was ready.

Some people decant everything. We don’t often decant because we spend so much time tasting each bottle that we want to reflect on how it changes. This is fun for us. In any case, if we taste a wine and it needs decanting, we can do that, but if we decant and the wine loses something, we can’t get it back.

We decanted the second bottle immediately and pow! The wine became more focused with the extra air and had the intensity we like. We wrote: “Much better bottle. Really focused and pure, bursting with fleshy fruit, white pepper and lychee. Just a remarkable taste. After an hour with even more air and warmth — too much? -- it seems to lose a bit of focus and intensity. The flavors are still good, but it doesn’t pop anymore. Next time we would still decant, but leave it in the fridge the whole time. We actually wish we had a third bottle.”

We appreciate that no two bottles of wine are the same. The wine in a bottle is a living thing that deviates and evolves differently than the wine that went into bottles ahead of it and behind it on the bottling line. If you don’t care how variables like climate, geography and time and temperature can affect the agricultural product we call wine, if you want consistency, drink a soda.

Still, we had rarely played with two bottles of the “same” wine back to back like that, with air and temperature, and we were eager to talk with Jeff Bundschu, president and CEO of Bundschu Company, parent company of Gundlach Bundschu, about our experience. He, his sister Katie and brother Rob Bundschu are part of the sixth generation involved in the family business. Katie’s separate passion project is called Abbot’s Passage Winery and Mercantile.

We called Jeff Bundschu and told him how the wines changed and tasted so different with air and warmth. “I’m kind of getting little chills while you’re saying that. That’s sort of been a telltale sign of a lot of wines off our estate. I think that’s probably because of the strong acid structure that we tend to get no matter what we’re growing.

“There’s no question that letting air in and, to your point, letting it warm up a bit” changes it, said Bundschu, 52, a big fan of aeration. “The juxtaposition with Gewürztraminer is that it’s really refreshing if it’s very cold but it [the cold] is going to restrain some of its nuanced flavors.

“I’m not surprised that that happens and it’s actually great that you caught that. So I basically think that it’s an important thing to remember with wine, especially from cooler regions. When you open the bottle you really do need to remember that it will change for you right in front of you and to think about that. Sometimes you have to be conscious of that happening. ….Wine really does change and that’s one of the things that’s magical about it,” he said.

We couldn’t agree more. It was theater for us, we told him, our entertainment for the night. And, of course, it started with an accomplished, versatile star. In 1858, after Jeff Bundschu’s great, great, great grandfather, Jacob Gundlach, purchased Sonoma land that he named Rhinefarm, Gundlach returned home to Bavaria and wed Eva. On their honeymoon, they traveled through Germany and France collecting rootstock for their Rhinefarm. Gewürztraminer was among the varieties Jacob brought to the Rhinefarm, which is located in what is now the Sonoma Coast AVA. (The Bundschus entered the picture after German immigrant Charles Bundschu joined Gundlach’s wine business in 1868 and seven years later married the eldest of Eva and Jacob Gundlachs’ offspring.)

We couldn’t agree more. It was theater for us, we told him, our entertainment for the night. And, of course, it started with an accomplished, versatile star. In 1858, after Jeff Bundschu’s great, great, great grandfather, Jacob Gundlach, purchased Sonoma land that he named Rhinefarm, Gundlach returned home to Bavaria and wed Eva. On their honeymoon, they traveled through Germany and France collecting rootstock for their Rhinefarm. Gewürztraminer was among the varieties Jacob brought to the Rhinefarm, which is located in what is now the Sonoma Coast AVA. (The Bundschus entered the picture after German immigrant Charles Bundschu joined Gundlach’s wine business in 1868 and seven years later married the eldest of Eva and Jacob Gundlachs’ offspring.)

(Gundlach Bundschu vineyards)

“Gewürztraminer has been a part of our history for the entire time that we’ve been a winery and honestly since my dad sort of reinvigorated the place in the early ’70s. It is our only and main tie to Germany. It holds a special place in our hearts,” Bundschu told us.

The oldest block of Gewürztraminer that the family has now, 11 acres in what it calls its Heritage Block, is 50 years old this year. In the early 2000s, he said, demand for its Gewürztraminer exceeded supply so the family talked to UC-Davis viticulturists about cleaning up its old budwood, which means assuring that it is disease-free and ready for propagation. When told it would take 10 years, the family planted seven acres of an Alsace clone instead in 2008. “And since then we have begun the process of cleaning up the original budwood and have a source row waiting for us to take and plant when we want to expand it,” Bundschu said. The now 320-acre Rhinefarm boasts steep hillsides and cool valley-floor location vineyards where a variety of grape types are sustainably farmed in 60 separate blocks.

The family’s dry Gewürztraminer, of which it makes 3,000 cases each year, is distributed nationally and sells out, half going to the mailing list and half to restaurants and select stores.

“It’s a cult wine but with a small c,” Bundschu said, laughing. “It’s hard to say. If most people can get through saying Gundlach Bundschu Gewürztraminer, then they have to get through their preconception that it’s likely to be sweet. So it’s never going to grab the headlines in a macro sense. We’re lucky enough to have fans of that but they’ve had to really find it and be introduced to it. They don’t just stumble on it by accident.”

Growing it is a challenge. Fruit set refers to the development of tiny green berries that, with luck, will grow into grapes, an indication of how much fruit could be harvested, data that informs the bottom line big-time.

“It’s the most uneven setting variety that we have. Some years you’re really short and some years you’re pretty long so if you’re going to have any kind of consistent supply you almost have to plant more than you need,” Bundschu told us.

To get advice from another family with experience with Gewürztraminer, this one dating from 1626, he called Jean Trimbach from the legendary Alsace family. “Jean stayed with us and worked the harvest with the Bundschu family at Gundlach Bundschu when I was 16,” Bundschu said. Jean passed along Bundschu’s questions to his brother Pierre, who runs the technical and winemaking part of the business. “He basically just said ‘Get used to it. It’s a varietal that never really sets evenly.’” It’s the first variety GunBun harvests each year and it’s picked in multiple sweeps at night, when the air is cool, to preserve the grapes’ acidity and minerality. Ten percent of the wine is aged in neutral oak and 90% is in stainless steel. The alcohol is a well-balanced 14.3%.

We were surprised to hear about demand for Gewürztraminer outpacing supply. Bundschu said that while some other wineries make dry versions, most Gewürz “gets sold for quite a bit less than ours, in the single digits, and then have a lot more residual sugar. We do ours bone dry.

“We haven’t really been fanatics about ‘no sugar’ over the course of our development. We try to work out what the best balance is. We always lean toward that more bright floral, citrus side of it.

“When it’s dry like that, you do give up a lot of the viscosity and some of the sort of richness that some of the sweeter wines have and we get around that through a technique that our winemaker learned from a winemaker in Burgundy,” Bundschu told us. The grapes are whole-cluster pressed. But before that happens, about 15% of the clusters are frozen for 48 hours, then thawed and pressed. “That simple act of freezing the bunches and then pressing them off… yields a juice that’s really viscous and sort of creates a mouthfeel that is a little similar to what it would feel like if it had sugar in it or a lot of sugar in it,” he explained.

That sounds a lot like playing with grapes.

Santé.

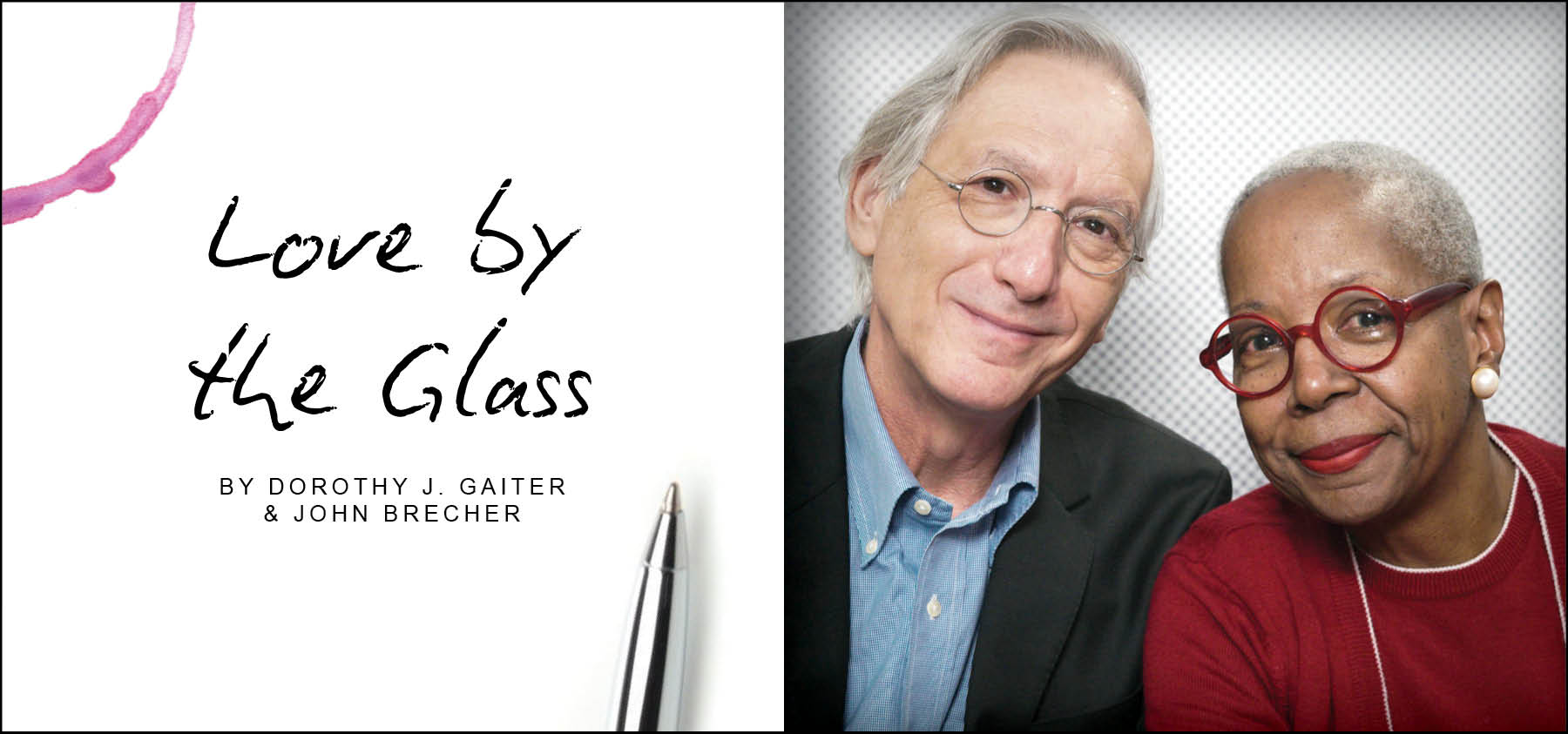

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner art by Piers Parlett