We had a chance to sit down with Bill Cromwell, the regional manager at Pinhook, a recently founded distillery that creates unique bottlings every single year. We also tasted some of his wares—ellipses in the following interview correspond to moments where Bill and the interviewer were imbibing.

Elliott Eglash: Can you tell us a bit about what makes Pinhook unique?

Bill Cromwell: Basically, what we do a little bit differently is we do annual vintages of bourbon, similar to wine. Most brands out there, when they go to bottle their whiskey, they pull thousands of barrels, and more or less blend them together to try and taste the exact same, so that every time you buy a bottle of Buffalo Trace or Woodford Reserve, it’s the exact same product. Nothing wrong with that, by any means.

Reliability, right.

Right, it’s consistency, you know. And there’s a time and a place for that. Our founder was a sommelier for a long time, so we started to look at whiskey a little bit more like wine, where the grain that we’re distilling with, the oak that we’re aging in, the temperature in Kentucky—all these things are going to fluctuate year to year, so the whiskey’s going to inevitably show differently. So when we go to bottle, we taste hundreds of our barrels, select the ones that we think are ready at any given time, and create a new blend, a new flavor profile, and essentially an annual vintage of bourbon. We paired each release with a promising young thoroughbred racehorse.

What’s the meaning behind the racehorses? They’re real horses.

They’re all actual racehorses. We actually started out—are you familiar with a distillery called MGP? MGP is a big distillery in Indiana, where a lot of folks still and would go and source their whiskey from. Like Angel’s Envy, Whistle Pig, George Dickel, Redemption, High West, they’ll go there, buy their whiskey, bring it back, blend it together, and create their own bottling with that. And they didn’t lie about it, but a lot of folks weren’t quite as transparent as they could be. So the name “Pinhook” is an old term for buying baby thoroughbred racehorses based on their lineage, raising the horses, and then selling the horses when they’re ready to run. And that’s essentially what we started out doing. We went down, bought some barrels—this was back when you could, you know, we got the barrels for like $460 each in 2011—started aging it, and then started releasing it. And we came to the conclusion that we were pinhooking bourbon.

They’re all actual racehorses. We actually started out—are you familiar with a distillery called MGP? MGP is a big distillery in Indiana, where a lot of folks still and would go and source their whiskey from. Like Angel’s Envy, Whistle Pig, George Dickel, Redemption, High West, they’ll go there, buy their whiskey, bring it back, blend it together, and create their own bottling with that. And they didn’t lie about it, but a lot of folks weren’t quite as transparent as they could be. So the name “Pinhook” is an old term for buying baby thoroughbred racehorses based on their lineage, raising the horses, and then selling the horses when they’re ready to run. And that’s essentially what we started out doing. We went down, bought some barrels—this was back when you could, you know, we got the barrels for like $460 each in 2011—started aging it, and then started releasing it. And we came to the conclusion that we were pinhooking bourbon.

Like investing?

Exactly, investing in the barrels of the future. And you know, when they bought the barrels, they didn’t have the name. There’s three founders, three buddies, and one of their best friends has a stable called “Bourbon Line Stables,” and all of his horses have either “bourbon” or “rye” in the name, which is kind of cool. So basically, each year we sit down with him and pick the horse that he thinks has the best chance to win the Derby. And bourbon and horse racing are both so true and connected in Kentucky—no one has ever really integrated horses into their brand, so we were kind of the first to do that.

How do the horses do?

Uh, good. So Bourbon War, he was one win away from being in the Derby last year.

…

At first, [our whiskey] was always 90-proof, because that’s what everyone else was doing. But at some point we started experimenting with it, and we realized that if you play around with the proof every time, you can come up with a more balanced, more complex whiskey, with a better finish and better alcohol integration. Like 95, 97, 104—I think as you taste these, they don’t taste that hot, you know?

So what’s the philosophy or method behind how you decide the proofing?

So, we’ll pull tons of little barrel samples and just proof it with different amounts of water, like to the half-proof. We’ve had whiskeys come in at 95.5, 93.5. Weirdly, the first time we saw this to be so true—we released our first rye a few years ago, at 93.5. The next rye we came to do came in at 97, and it felt softer at 97 than at 93.5, and that was just because of that particular batch of barrels. So, it’s just always going to be different, it’s always going to show differently. And sometimes it tastes better and more approachable—longer finish, more complex—at 98 proof than 96 proof. It’s crazy what one or two will do.

So, we’ll pull tons of little barrel samples and just proof it with different amounts of water, like to the half-proof. We’ve had whiskeys come in at 95.5, 93.5. Weirdly, the first time we saw this to be so true—we released our first rye a few years ago, at 93.5. The next rye we came to do came in at 97, and it felt softer at 97 than at 93.5, and that was just because of that particular batch of barrels. So, it’s just always going to be different, it’s always going to show differently. And sometimes it tastes better and more approachable—longer finish, more complex—at 98 proof than 96 proof. It’s crazy what one or two will do.

And it’s just a matter of tasting until you get the right ratio?

Exactly. [laughs] It’s a lot. But as opposed to trying to create this homogenized product that’s always the same, it’s always evolving.

…

We do the flagship bourbon around the end of summer, so next July or August you’ll see a very similar bottling to this—same color of wax, same style of label, different horse, and slightly different flavor profile.

And different whiskey? Are you trying to preserve some kind of identity or unifying traits?

Not flavor-wise. I mean, it’s the same mash bill, and it’s the same distillery, right, so there’s gonna be some similarities. But, like, this might show a little more fruit, and next time it’ll show a little bit more vanilla. But overall, you won’t see too drastic of changes. I think in wine vintages year to year you see some subtle changes, but the same producers kind of have a similar approach to each bottling.

On the subject of wine—you say you’re trying to approach making whiskey a little bit like making wine. In winemaking culture, you have the concept of terroir, the expression of a place. Do you have anything comparable, any guiding principle?

I couldn’t say it to the same extent as terroir. But just the fact that like, think about it: it takes one tree to make one oak barrel. No two trees are going to be the exact same thing. And each different oak barrel from each different tree is going to affect the whiskey inside differently every single time. And people like, for example—when Maker’s Mark bottles Maker’s Mark, they do a thousand barrel dumps at a time. They dump 800 barrels, and then based on how that tastes, they know which other 200 barrels they need to add to make it taste like Maker’s Mark. So that when you buy it, it’s the exact same: ten years ago, ten years from now. And we don’t ever care about doing that. We just want it to be the best whiskey, as opposed to the same whiskey. For example, to get on the tasting panel at Maker’s Mark, or probably any big bourbon brand, you line up 20 glasses—19 of them have Maker’s Mark in it, and one’s a little bit different. You have to be able to pick it out. But if that one is better, they can’t do anything with it—they just have to make it taste like Maker’s Mark. We don’t put ourselves in a box.

…

So, I’m sure you’re familiar a little bit with E.H. Taylor?

A little bit, yeah.

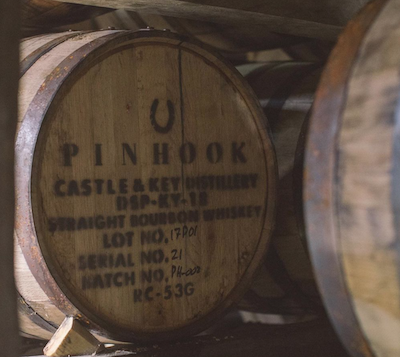

Right, everybody is these days. So E.H. Taylor built his own distillery, the Old Taylor Distillery, in 1887. And when he built it, it was sort of the first bourbon tourist destination. No one took a lot of pride in their facility—you could still go to the supermarket and, like, fill your jug up right from the barrel. He wanted people to really come and embrace the process. And he did, and he had a great run. It was the first distillery to ever produce a million cases of bourbon. He built an actual castle for people to come and see this place. Natural ground water, spring water, right on site. It had a good run, but it was decommissioned in 1972. We were fortunate enough to know the two people, through some friends, who were buying it and bringing it back to life. It’s now called “Castle & Key,” same castle still lays there. So the first two whiskeys that we were able to release with our own distillate, it’s also the first whiskey coming out of this, one of the most iconic distilleries of all time, in almost 50 years. So it’s a big year for us.

Right, everybody is these days. So E.H. Taylor built his own distillery, the Old Taylor Distillery, in 1887. And when he built it, it was sort of the first bourbon tourist destination. No one took a lot of pride in their facility—you could still go to the supermarket and, like, fill your jug up right from the barrel. He wanted people to really come and embrace the process. And he did, and he had a great run. It was the first distillery to ever produce a million cases of bourbon. He built an actual castle for people to come and see this place. Natural ground water, spring water, right on site. It had a good run, but it was decommissioned in 1972. We were fortunate enough to know the two people, through some friends, who were buying it and bringing it back to life. It’s now called “Castle & Key,” same castle still lays there. So the first two whiskeys that we were able to release with our own distillate, it’s also the first whiskey coming out of this, one of the most iconic distilleries of all time, in almost 50 years. So it’s a big year for us.

Do you view yourselves as successors to that heritage?

I wouldn’t call it successors. On paper, the reality is, we have a contract with them. We’re just the first to do that, and as of now, the only to release. So if people want to try Old Taylor Distillery, now called Castle & Key, they’re drinking Pinhook. Castle & Key releases some of their whiskey, but as of now, it’s not making its way to the East Coast. So people who want to do so get to experience it through Pinhook.

…

Very exciting project that we started last year. So, as we were moving into the whiskey we were going to release out of Castle & Key, we still had some barrels that we’d previously sourced—great whiskey inside, we wanted to do something unique with it. So we came up with the idea of this Vertical Series. Basically, we’re going to take a small amount of those barrels every year, and do a release for the next nine years. Because they were all distilled roughly at the same time, within a month or so of each other, all in the same part of the brickhouse, so people can follow the same whiskey from the same set of barrels as it ages from four to twelve years old. People love to collect projects like this—our founder calls it the perfect storm of bourbon collecting. The age will go up, the proof will go up, demand will go up, but the production will go down.

Do you have the kind of die-hard, obsessive following that’s going to get every year’s vintage?

We have a ton of folks like that. I think the six-year is going to be the big one, where it’s gonna be a little tougher to get. It’s 150 barrels, but that’s for the whole country, so there’s a good bit of it to get the word out there and spread it. Once it gets to six, seven years, the brand’s gonna be big and people are gonna know it, and people are gonna go back and start looking for the four- and five-year, but everybody drank it. This is on the shelf for 49 bucks, 50 bucks, people just buy it and drink it. And then they realize how collectible it is. So I tell anybody who’s going to work with the series, just buy it and hold like three bottles back. Sell it, because obviously we want people to be introduced to the story, and the collectability of it. But for y’all’s sake, hold two or three bottles back and just forget about them. And then in four or five years you can line them all up and see how it goes.

…

We do a limited bottling of each [vintage] at a higher proof. So it’s the same mash bill, the same age, this one’s just bottled at 114.5 proof.

Do you have a sense of how the flavor profile compares?

When we first started out, we were doing it all cask strength. But a huge part of what we do is that proofing process, where we look for the perfect proof every single time. So now we call it perfect high proof.

For the slightly more alcoholic crowd.

Exactly, exactly. Anything cask strength or really high proof, I think you’re always going to get a bigger, bolder bourbon with more flavor profile. And then people can choose to water it down as they like. I think you get some sweeter notes because of the bolder flavors.

Do you have a favorite vintage that you’ve made?

Personally? The cask strength Rye Humor is probably one of my favorite things, and it’s been pretty highly regarded as one of our most popular releases.

So, out of curiosity, for someone who’s getting started learning about whiskey, what do they need to know about your product?

People are constantly looking for something different, and I think we offer that at a pretty good value, with great flavor profile. But when it comes to whiskey, it’s about finding what you like. When you look at whiskey, you look at this huge umbrella. People always ask me what’s the difference between bourbon and whiskey? Usually they mean scotch, but bourbon just falls under this umbrella. That is hands-down my favorite, because I stick to the American whiskey side. I think it usually comes across a little bit sweeter. I think that’s something we don’t always showcase. I think we’re able to avoid a lot of it. It’s too much vanilla, too much caramel, too much oak sometimes. But, you know, to each their own. Rye whiskey, personally, I think, holds up better in cocktails.

People are constantly looking for something different, and I think we offer that at a pretty good value, with great flavor profile. But when it comes to whiskey, it’s about finding what you like. When you look at whiskey, you look at this huge umbrella. People always ask me what’s the difference between bourbon and whiskey? Usually they mean scotch, but bourbon just falls under this umbrella. That is hands-down my favorite, because I stick to the American whiskey side. I think it usually comes across a little bit sweeter. I think that’s something we don’t always showcase. I think we’re able to avoid a lot of it. It’s too much vanilla, too much caramel, too much oak sometimes. But, you know, to each their own. Rye whiskey, personally, I think, holds up better in cocktails.

Are you a cocktail guy?

I am, yeah. I came from the bar world a little while before this, and yeah, definitely made some cocktails. I definitely still like to do it at home. Usually I’ll have bourbon, neat, or maybe a little bit of ice. And rye whiskey I mix into cocktails.

I love a good old fashioned.

It’s a good time. And that’s why you add a little bit of sugar. Traditionally, it is a bourbon cocktail, but…

As long as you’ve got the whiskey in there.

Exactly, exactly.

How is it being back in New York?

It’s been great. Our founder owned two whiskey bars here in the city. One was called Maysville, on 26th Street, along with CHAR No. 4, down in Carroll Gardens, in Brooklyn. So this is hands-down our biggest market. We have a great following here. It’s great to connect with some old Pinhook friends, and some regular friends as well. Happy to be here. You know, there’s worse things to do than pour whiskey for folks who are interested in drinking and hearing about it.

Not a bad gig if you can get it.

And it’s good whiskey, with a good story to tell.